Abkhazia in the early Middle Ages: History, the Silk Road, and Fortresses

Exploring the Misimian Branch of the Silk Road

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Abkhazia is one of the most unknown corners of Eurasia. Both geographically sequestered from neighboring regions and geopolitically isolated following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Abkhazia is terra incognita for most. One of the few places where the disintegration of the Soviet Empire turned violent, in 1992 Abkhazia broke from newly independent Georgia which triggered war and ethnic cleansing that only ended in 2008. Initially an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Georgian SSR, as the main titular republics broke away from Moscow, Abkhazia broke away from Tbilisi. Intense fighting only lasted a few years, but the conflict renewed in 2008, and with Russian assistance Abkhazia declared formal independence. Due to the Soviet Union closing itself off from the outside world and its geopolitical situation since 1992, Abkhazia has remained effectively isolated from the outside world. Yet, historically Abkhazia was never so isolated. At one time it hosted one of the most important sections of the Silk Road. During the era of the Emperor Justinian almost all Silk Road trade that reach Byzantium would have came over the Caucasus Mountains into Abkhazia. From there goods and travelers would be shipped to ports in the empire. This history is all but forgotten, yet nevertheless very interesting and deserves to be told. This essay will look at the history of Abkhazia during the early medieval period when it was a major crossroads on the Silk Road.

It is a common misconception that the Silk Road was a single linear path from China through Central Asia and Persia to Europe. Instead it was a series of branching trade routes connecting all of Eurasia into an integrated trading network. For the entire distance, from the frontiers of China to Europe, there were always multiple concurrent trade routes which would eventually converge on a handful of major urban trade centers. For example, when leaving China caravans could choose to go northwards to Mongolia and then proceed westward across the steppe, or they could go northwest through the Hexi Corridor, to the Jade Gate. After passing through the Jade Gate into the Tarim Basin, caravans usually took one of three routes. The southernmost road took them along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert through Lop Nor, to Khotan, and then Kashgar. Another route went through Turfan, Kucha, Aksu, culminating at Kashgar. From there caravans would either take the Irkeshtam or Torugart Pass into modern Krygyzstan, or go south through the Pamir and Karakorum Mountains to India. The third route branched off from Turfan, going northwest through the Danbancheng Pass and then westwards along the northern face of the Tienshan Mountains.

The multiple concurrent routes allowed caravans to bypass certain cities, oases, or entire regions. The reasons a caravan or merchants would want to avoid certain places are no different than what would discourage business and investments today. High taxes, danger from war or bandits, or political reasons could motivate caravans to avoid an areas and take a different route instead.

The Creation of the Silk Road in the 6th century

These trans-Eurasian trade routes from China to Europe had existed since the 1st century AD, when the Han Dynasty of China and the Roman Empire were both at their heights of power. Han armies conquered modern Xinjiang and marched as far west as the Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan, while Rome conquered the entire Mediterranean basin and much of the Black Sea. Between them was the Persian Parthian Empire, which occupied much of the lands from Mesopotamia to Central Asia. With these three great empires travel was made safe for merchants and caravans. The Roman imperial elite spread across the provinces created a large and sufficiently wealthy consumer market that attracted long distance merchants from beyond the empire’s frontiers. Yet, this Golden Age across Eurasia was not to last. The 3rd century saw the collapse of the Han Dynasty and destabilization of the Roman Empire, and as a result Eurasian trade severely declined.

It was only in the 6th century did Silk Road trade see a revival, eventually surpassing its previous iteration in terms of volume and scale of international trade. This is thanks to three factors. First, the Eastern Roman Empire, later called the Byzantine Empire, experienced a period of ascendancy under the Emperor Justinian. Byzantium would suffer a series of catastrophes after Justinian, but as the Islamic Caliphate rose it largely replaced Byzantium as a market for silk and other traded goods. Secondly, the reunification of China under the Sui, and later Tang Dynasty allowed for the mass production of silk textiles and other goods for export. Additionally, the Tang conquered the entire eastern half of the Eurasia steppe, and maintained their authority by paying the steppe nomads with large amounts of silk. These nomads would in turn sell the tributary silk they received westward, further stimulating Eurasian trade.

Third, and most consequential, was the emergence of the Turks into world history. The Turks were originally a nomadic people living somewhere near the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, who were particularly talented in metallurgy. In the middle of the 6th century, the Ashina clan headed by Bumin and his brother Istemi led a revolt against the reigning hegemon on the eastern steppes, the Rouran Khaganate. The successful revolt was then followed by their swift conquest of the entirety of the Eurasian steppes from the borders of China to the Pontic Steppe in modern Ukraine. The creation of the Turkic Khaganate allowed trade along the Silk Road to flourish for the same reason the Mongol conquests did. The Turkic empire empire made it safe for caravans to travel and transport their goods without fear of robbery.

The Misimian Branch of the Silk Road

Yet, in western Eurasia there were two geopolitical obstacles that limited these Eurasian trade networks from reaching Byzantium. First, elements of the former Rouran Khaganate fled westward from the Turks and occupied the Pannonia and much of the Balkans. These nomads became known to the Byzantines as the Avars. Coinciding with the Avars arriving to Europe, the Slavic migrations began from north of the Carpathians into the Balkans. Due to his attempt to reconquer territories of the western Roman Empire which had been lost since the 5th century, Emperor Justinian had left the frontier along the Danube undefended. With the frontier stripped of its defenses the Avars and Slavs poured forth, devastating the Balkans. For centuries the Balkans would be left outside of imperial control.

The second obstacle was the Persian Sasanian Empire who forbid Sogdians from entering into their lands. Sogdians were an Iranic people who lived in modern day central Uzbekistan, in the oasis cities of Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent primarily. Since the 5th century the Sasanians had fought the Hephthalites, or White Huns, on their Central Asian frontier which roughly ran along the River Oxus. In the following century the Turks swept into Central Asia and conquered the Hephthalties, bringing the Sogdians under their domain. Under Turkic rule the Sogdians became both administrators for the Turkic Khaganate and also the merchants and caravan drivers who controlled the majority of the Silk Road trade. Similar to Jews in Europe and Armenians in the Near East, the Sogdians established a diaspora network across Eurasia which allowed them facilitate long distance trade. As the Turks replaced the Hephthalites as the Sasanian Empire’s enemy beyond the Oxus, the Sasanians came to view Sogdian merchants as nothing more than spies for their Turkic masters. This was entirely justified, nomadic rulers regularly used caravans and merchants as spies to reconnoiter invasion routes and make observations on the state of a potential enemy. When the Turk Khagan sent a Sogdian diplomatic-commercial mission to the Sasanians, the Persians famously burned all the silk and strictly forbid any further Sogdian merchants from entry into their kingdom. With the Balkans overrun by Avars and Slavs making it too dangerous for caravans and Persia closed as a transit route, caravans needed a different route to Byzantium.

In later centuries, most Eurasian trade which reached the Byzantine Empire transited through conventional routes across Persia and the Middle East to the Levant, or across the Pontic Steppe to ports in Crimea. Yet, due to the unique geopolitical situation in the 6th century a different route was taken. Caravans would travel across the steppe, often through Chorasmia, the modern Khiva oasis of western Uzbekistan, before passing the Caspian Sea to the north. After the Caspian, caravans turned south-west towards the Caucasus Mountain range heading towards the Alans, an Iranic nomadic people who lived in the lowlands and mountain valleys of the western North Caucasus, in what is today the regions of North Ossetia–Alania, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia in the Russian Federation. After passing through Alania, caravans would cross the Caucasus Mountains over the high passes bringing goods to ports on the Black Sea. These ports were cities originally founded by Greek colonists in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, including Sevastopolis, modern Sukhumi, Pitius, modern Pitsunda, and Phasis, modern Poti. From there goods would be shipped to Constantinople, Trebizond, and elsewhere.

An obvious question is why did the Silk Road go over the Caucasus to Abkhazia, instead of simply accessing the modern day Russian ports of Anapa, Novorossiysk, Tuaspe and Sochi, many of which were also originally founded as Greek colonies and trading posts. Similar to the problems plaguing the route across the Pontic Steppe in the 6th century, it was simply too dangerous. Later known as Circassia, this region was infamous for rampant piracy in Greco-Roman and Byzantium times. In the early medieval period this region was known as Zichia, and under the Emperor of Justinian an eparchy was created for Zichia. But due to the danger clergy and church officials ever ventured there and eventually in the 9th century the eparchy was abolished.

This general route from the Alans to the Black Sea over the Caucasus is known as the “Misimian Branch” of the Silk Road. There were several routes through different gorges and passes which could be traversed, but the main route was up the Teberda River valley in modern day Karachay-Cherkessia, over the Klukhor Pass, and down the Kodori River in Abasgia, modern Abkhazia. The name “Misimian Brach” refers to the general route from the Alans to Abasgia over the western Caucasus, encompassing the several different paths over the mountains, although the term specifically refers to the Misimians, an ancient people who lived in the upper Kodori Valley.

These trade routes over the western Caucasus had existed since the 1st century AD during the Roman Empire. Strabo wrote in his “Geographica” that Sebatopolis was a great trade emporium, and near modern Sukhumi, capital of Abkhazia, at the Gerzeul fortress a large caches of Roman coins from the 2nd century were found with the depiction of the Emperor Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius and others. Near the Tsebelda fortress amphora were found with patterns indicating they were made in Syria. In the 1980’s, Soviet archeologists uncovered a burial site just south of the village Kurdzhinovo on the Bolshaya Laba River in Karachay-Cherkessia later known as “Moshchaya Balka”. They found several pieces of Chinese silk, with some pieces having Buddhist inscriptions, a Buddhist flag, a Buddhist icon, and products from Byzantium and Sogdia. The graves where connected to a nearby hilltop fort and was dated to sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries. It is located on a caravan route that connected to the Kodori River valley after having crossed the high Caucasus.

As the geopolitical situation evolved, other more convenient trade routes became more popular among caravans. During the 13th and 14th centuries when Italian mercantile city-states established trading posts on the Black Sea with the Mongol Empire and later Golden Horde the routes over the western Caucasus saw a revival of Silk Road traffic, and later in the Ottoman Empire a number of old Roman fortress in Abkhazia were refortified, indicating some degree of modest trade continued.

History of Abasgia

For this essay I want to look at the Misimian Branch of the Silk Road in detail, specifically the routes taken over the mountains, and what fortress, military infrastructure and people would be encountered while travelling along it. My personal research on this topic began with reading Byzantine history, specifically the diplomatic missions of Leo the Isaurian and Zemarchus, both of whom travelled through the Kodori Valley and the Misimians Branch of the Silk Road. Most caravans traveled south, from the Alans up the Teberda Valley, over the mountains and down the Kodori Valley to Abasgia and Byzantium, but because of my research I have looked at this region from the standpoint of the Byzantines. This means, instead of beginning in the north we will start from Abasgia, working our way up through the Kodori, and down the Teberda. The objective is to know this route well enough that I (or anyone reading) could take this information and travel through this route today as if we were caravan merchants along the Silk Road or Byzantine diplomatic officials heading to the steppe nomads. Essentially this essay will be an annotated map of a particular segment of the Silk Road. But before beginning, a brief review of the region and its history is required for context.

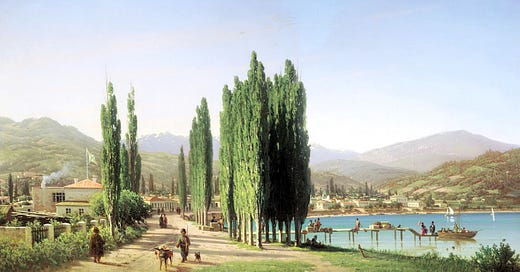

The Abasgians were people that lived in the coastal lowlands of modern Abkhazia, and the historic Abasgian Kingdom was an early medieval state that encompassed modern Abkhazia and parts of modern day western Georgia. Located at the eastern most point of the Black Sea, Abasgia was just northwards along the coast from ancient Colchis, famous from the legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece. Warm winds and rain clouds are blown eastward across the Black Sea and are effectively trapped over Abkhazia and western Georgia by the high Caucasus and the smaller ranges that exist further inland. Likewise, the tall Caucasus blocks cold northerly winds, and this creates a uniquely warm and rainy climate, somewhat similar to the Northwest Pacific coasts of America and Canada. The western Caucasus are taller than the mountains in the east, thus having more snow and glaciers on their high peaks. The melting ice and snow creates many large rivers. In the South Caucasus these include the Kodori, Rioni (the ancient river Phasis), and the Inguri Rivers, while in the North Caucasus there is the Kuban River and its various tributaries such as the Laba, Zelenchuk, Belaya and others. Thanks to the warm, rainy climate and several large rivers, the eastern Black Sea is uniquely green, rich in plant life and covered in thick forests. Both historic Abasgia and Colchis are considered subtropical climes. Whereas Colchis is generally flat, Abkhazia is mostly mountainous and has only a narrow lowland coastal region. Its inland regions are a series of hills and mountains rising up the high peaks of the Caucasus with deep gorges and valleys cutting into the mountains.

In the 8th century BC, Greeks began colonizing eastern Black Sea coast. In search of metals, colonists from Miletus settled the Black Sea coasts creating cities and trading colonies. According to myths, the Dioscuri brothers of Castor and Pollux travelled with Jason and the Argonauts to Colchis, but decided to stay behind instead of returning to Greece. According to these myths they founded the city of Dioscurias, which was later renamed during the Roman Empire as Sebastopolis and in modern times as Sukhumi, later becoming capital of Abkhazia under the Soviet Union. On the contray, Strabo writes Dioscurias was founded as Milesian colony, and the Greeks mixed with the local people. Greco-Roman cultural and political influence was largely limited to the coastal lowland area and failed to fully penetrate into the mountainous highland regions.

During the Roman and Byzantine periods, imperial control over the eastern Black Sea regions was maintain by controlling access to salt. As there was little salt domestically in the region, the local peoples were dependent upon salt imports that the Roman brought from Chersoneses, modern Sevastopol in Crimea. The Romans, knowing how dependent local tribes were, would only sell salt to political loyal tribes and peoples. In the 2nd century the kingdom of Lazica was formed, with its capital Archaeopolis located at modern Nokalakevi in western Georgia. What were the ancient lands of Colchis became Lazica, as well as parts northeastern Anatolia and the Pontic Mountains. Lazica became a Roman protectorate and a buffer state against both the Persian Empire to the east which ruled Iberia, modern Tbilisi and eastern Georgia, as well as the nomads to the north. During this period the Abasgians were under the dominion of Lazica. Reported in several ancient texts, Lazica would kidnap the best looking Abasgian boys, castrate them, and sell to the Romans as eunuchs. This continued into the Byzantine period, with Christians having mixed feelings towards this practice. The Emperor Justinian attempted to outlaw the trade, but like in modern times, state laws banning illicit trade in distant, mountainous frontiers are difficult to enforce. By contrast, other Christians had a more favorable view, believing eunuchs were spared from carnal temptations and thus would enter the kingdom of Heaven more easily.

Abasgian political life and culture developed under strong Byzantine influence. Under the Emperor Justinian Abasgia was Christianized with many basilicas built and missionaries sent to make conversions. Later in the 660’s the Archbishopric of Abasgia was created and in 750 the Abasgian church became autocephalous. The creation of an independent church was of the greatest importance of Abasgian statehood. The Church created a cadre of educated and literate Abasgians who could be used in state service, and a canon of national saints would have helped create sense of history and identity for the people. In the Byzantium Empire there was effectively no division between the church and state, and membership in the imperial community as equivalent to membership in the church. To be “Roman” was not a legal or civic identity was nationality is today in many countries, but an ecclesiastical concept. Medieval Roman (Byzantine) identity was synonymous with the Church, similar to how modern Russian, Serbian or Georgian identities are conjoined with their national churches, or how Muslim and Jewish identities are fundamentally ecclesiastical.

With the creation of the Abasgian Church, secular state structures formed. In the 790’s Leon II threw off direct Byzantine rule and created the Kingdom of Abasgia. King Leon II was the grandson of the Khazar Khagan, and it is likely that he asserted independence from Byzantium with Khazar support. Abasgia remained hostile to the Islamic Caliphate and the reigning Isaurian Dynasty in Constantinople had similar blood ties to the Khazars, thus Byzantium tolerated Leon II’s actions. Despite formal Abasgian independence as well as Byzantium’s weakness during the 7th and 8th centuries, Abkhazia remained firmly in the Byzantine cultural and political orbit. Throughout the entirety of the Byzantine epoch there was a wide diffusion of Byzantine influence in the forms of fashion, material, luxury goods, and weapons. The most long lasting influence was Byzantine assistance in architecture, specifically in military fortifications and churches. It is likely that architects and military officers were sent to Abasgia to assist them in construction efforts.

Why did they build these fortresses?

Abkhazia’s geography is a narrow lowland coast, with numerous valleys and gorges cutting into the mountains. Nomadic invasions and caravan traffic would be entirely funneled through these defiles, and thus almost all fortresses were located either in or at entrances of these valleys. The purpose of the forts was twofold, in part for defense but also as custom posts for taxing travellers. These routes were frequented by merchants more so than nomadic invaders, thus road tolls and customs taxes would have been very profitable for whoever controlled the posts. This is not to understate the threat posed by the steppe nomads, it is likely the initial impetus for their construction was to guard the passes over the Caucasus during the period of the barbarian migrations which tore down the western Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries. One such example was recorded by Roman poetry.

“... across the Phasis are driven

Cappadocian mothers, and seized from their ancestral stables

captive herds drink the frosts of the Caucasus

and exchange the fields of Argaeum for the forests of Scythia.

Beyond the Cimmerian marshes, the Taurian gates,

the flower of Syria is enslaved. And the savage barbarian is not satisfied

with spoils: they slaughter the pick of their booty.”

These verses were written by the poet Claudian, referring to a Hunnic invasion in 398 during the reign of the Emperor Arcadius. The Huns passed over the western Caucasus Mountains, through Lazica into Anatolia, before being met by an army under the Consul Eutropius. Under the Emperor Justinian military infrastructure in the region was renovated and upgrade.

Abkhazia is bisected by multiple valleys, all of which have numerous fortresses spread along their course, as well as several major fortresses along the coast. For the sake of brevity as well as my personal research purposes, only the medieval Abasgian capital Anakopia and fortresses in the Kodori Valley will be covered further ahead in the essay. That being said, there are some generalities and standard features of Abasgian fortresses that apply to sites not specifically mentioned in this essay.

Fortresses are usually located in open and elevated spots in valleys and gorges, and are neither hidden nor disguised by the landscape or foliage. Roman strategic thought believed that fortresses were statements of Roman power and would overawe allies and enemies alike. For a state it is preferable for others to be so impressed by your power that they are awed into submission and deterred from attacking. Fortresses often had at least one tower, but if it was located on a high cliff or mountaintop a tower was naturally not needed for observation purposes. Water sources were always enclosed within the fortress walls, at least a stream but optimally both a stream and a cistern that could collect rain water. In every fort there was a church or basilica located at the center of the fortress, often at commanding, highly visible position. The road leading up the fortress gate usually made a sharp right hand turn, and the entrance was flanked by a tower or a protruding wall. Geographically forts were placed along the main transport routes on roads or on the coast, and were at least one day’s armed march with baggage away from the next outpost. In Abasgia, almost all forts were made from stone bricks, with walls several meters thick and usually around 10 meters tall.

Anakopia

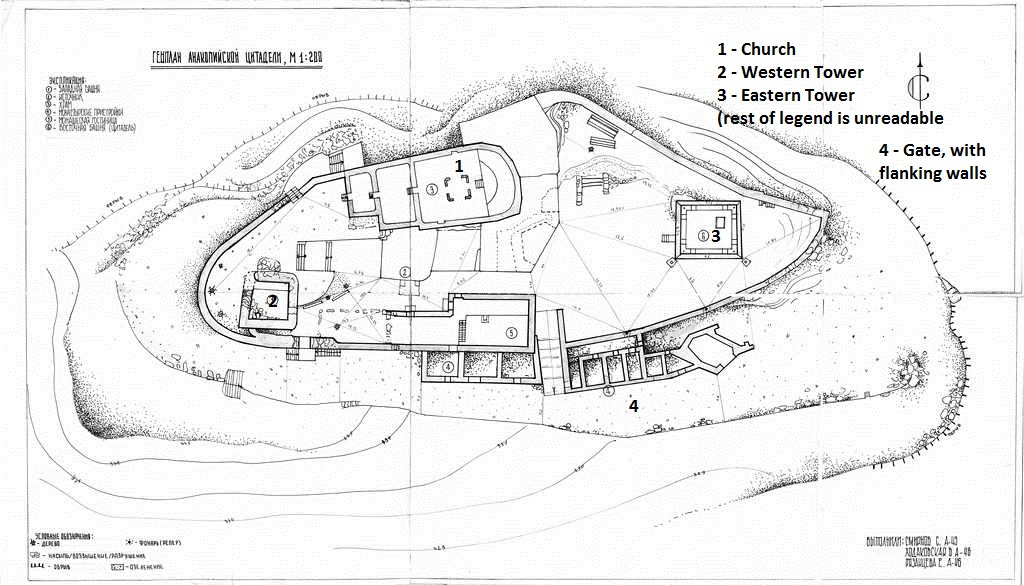

Sometimes referred to as the Tracheia Fortress by Greek speakers, Anakopia was the capital of Abasgia from the 8th to the early 9th century, and is the most well-known and commonly visited fortress by tourists. Located northwards up the coast from Sukhumi, Anakopia is located where the already thin coastal lowland strip narrows even more so. Similar to the Derbent fortress, Anakopia is a fortress and citadel on a small mountain with a city below. The citadel is about 330 meters above the sea level. Two parallel walls would have run from the mountain to the sea enclosing the city and port facilities. From the top of Anakopia, the fortress commands a panorama view of the coastal lowlands in both directions.

Going up from the lowland towards the Anakopia citadel, the path zigzagged left and right up the hill. Part way up the hill was the main fortress wall which spanned 450 meters in length and had 7 towers which were spaced 30-50 meters apart. Catapults or other forms of artillery could be placed on the towers. The gate itself was located behind a tower, which gave defenders the ability to inflict flanking missile attacks from above on besieger who were making an assault on a gate. Other smaller gates were located along the wall near towers. During the 737 siege by the Arabs, the Abasgians sallied out from these side gates to harass the besieging Arabs, which successfully broke the siege. After the main gate the path continued to zigzag up the hill to the citadel on top. Located in the citadel was two, two-storied towers and a large temple at its center called the “Blessed Virgin Mary Basilica”.

From the citadel other churches could be seen on top of neighboring mountain tops. This was likely due to a syncretic mixture with pre-Christian pagan beliefs as Abasgian pagans worshiped on top of scared mountains. In fact, the syncretism between Abasgian paganism and Christianity ran much deeper. Pagan Abasgians worshiped a Goddess-Mother as their main deity, and following their conversion the Abasgians seem to have favored the Virgin Mary uniquely so. The Anakopia basilica housed an icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it was said to have miraculous powers and was not made by human hands but instead suddenly appeared one day, sent down from above by the higher power. Underneath Anakopia is a large cave, now called the New Athens Cave, and during pagan times lambs were reportedly sacrificed here to a fertility goddess Afy, the lightning thrower. Later a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary was built in the cave. The syncretic parallels are quite obvious. A site for pagan fertility worship after Christianization became a site worshipping the Virgin Mary, which is at its core a story worshipping fertility. Whether the reported pagan lamb sacrifices to a fertility god have any significance to Christianity more than mere coincidence is not obvious to me, but I sense there is some meaningful relation between the two.

As mentioned previously, Anakopia was not the initial capital of Abasgia. The capital had been Sebastopolis, but due to the Arab invasions in the early 8th century the capital was relocated to a more defensive site. The Arab Muslims had first reached the Caucasus in the 650’s, but these initial forays were mere raids. Only at the turn of the 8th century did the Arabs establish a permanent presence in the South Caucasus region, refortifying the Darband pass in the east and triggering a century long conflict with the Khazar Khagante to the north. During this period Abasgia seemed to have been semi-autonomous under Byzantine oversight, along with friendly relations with the Khazars who controlled the North Caucasus. Allied to Byzantium and the Khazars, the two primary enemies of the Caliphate, Abasgia came under severe Arab during the early 8th century. The peak of Arab-Khazar conflict occurred in 736 and 737, during this period the Arabs penetrated north through the Darband pass and encircled the Khazar army and the Khagan, forcing the Khagan to convert to Islam. Sometime either just before or after this campaign, the same Arab commander Marvan “the Deaf” crossed the Sarapanis Pass from Kartli, modern central Georgia, into the ancient Colchian plain. The Arabs went north, destroying Sebastopolis, reaching Anakopia where they were stopped by its fortifications. It is also possible that during this time an Arab detachment went north through the Kodori Valley into Alan territories in the North Caucasus. Sources speak of great devastation inflicted by the Arabs, describing them as “like a dark cloud of locusts and mosquitoes”. It was during this conflict that the Abasgian capital was relocated to the much more defensible site of Anakopia, and similarly the Khazars also moved their capital north from Semendar, near modern Makhachkala, to Atil on the Volga, near modern Astrakhan.

A local Abkhazian legend tells a story of political intrigue centered in Anakopia. The story goes, an Abasgian prince, brother of the king, wanted to seize the throne, and so he contacted Constantinople and asked for help. His brother the king favored the Arabs, so Constantinople who was locked in constant war with the Caliphate was happy to see the king gone and agreed to assist the Prince. The King’s daughter, named Anakopia-Ipkha had been living in Constantinople, but had expressed her desire to return home. The Romans granted her request, and sent her home with several servants and a chest full of toys. Upon returning home there was a great feast and celebration in the fortress. After everyone was asleep the servants began to stir, as they were not really servants but soldiers and the chest full of toys was actually full of weapons. The Roman soldiers opened the gate, allowing the Prince and his men to seize the fortress and citadel. They later named the fortress Anakopia after the old king’s daughter who made their coup possible.

This tales likely speaks of political schemes in Abkhazia during the 11th century, between Alda the Ossetian, George I of Georgia, and Byzantium, before the empire was fatally weakened following the great catastrophe at Manzikert.

The Kelasuri Wall – “The Great Wall of Abkhazia”

Less than 10 kilometer southeast down the coast from Sukhumi, ancient Dioscurias/Sebastopolis, begins the Kelasuri Wall. Starting on the left bank of the Kelasuri River, the wall runs 160 kilometers long eastward, cutting inland across the foothills and low mountains, up to the right bank of the Inguri River in Georgia. The wall encloses nearly the entire lowland coastal plain. Similar to Antonine Wall and Hadrian’s Wall in Britain and the Great Wall in China, the Kelasuri Wall was a long line of fortifications, walls, towers and forts meant to safeguard civilized life from barbarians to the north. The wall was not entirely continuous, at places it was interrupted by gorges, cliffs, forests and other obstacles which would impede enemies sufficiently enough to not require additional fortifications. On what remains of the wall, images of animals craved into the rocks have been found, including bears, deer, lions, goats, and oxen. One block in particular has a cross, with a lion and a bull below it, with the bull bowing to the lion while the lion holds the bull by the horn.

The remains of 279 towers have been discovered along the length of the wall, with 100 partially standing and the rest nearly or almost completely in ruins. The western half of the wall up to Moki River had the heaviest concentration of fortifications with 200 towers, while the most eastern section between Tkvarcheli and the Inguri River there were only 4 towers. Most towers were rectangular, 7 by 8 or 8 by 9 meters, and 4–6 m tall. Each tower had a door in its southern wall and a narrow staircase up to the higher floors. Embrasures for missile and projectile weaponry were usually located in the towers' northern and western walls on the second floor. Similar to fortress elsewhere in Abkhazia, forts along the wall tended to be located on hilltops and along transport routes, and always a day’s march from the sea. As valleys were the routes taken by nomadic invaders from the north, the wall primarily guarded valley entrances, while the hilltop forts functioned as signal beacon posts. Coming under attack, the hilltop signal beacon would light a fire to alert forts along the wall and settlements to the south near the coast, and with a bit of luck reinforcements would arrive before the enemy could break through.

Towers and forts were concentrated at the entrances to gorges and river valleys, which gave the wall the name “Kelasuri”. From the Greek word “kleisoura” meaning defile, it was used to describe mountain passes which had military significance. With the collapse of Byzantine power in the Syria and the Levant following the battle at Yarmouk in 636, the Byzantine-Caliphate frontier eventually stabilized along the Taurus and Anti-Taurus Mountains. For the next several centuries the two empires were on a permanent war footing with each other in highly mountainous terrain. Due to the geography, as well as the empire’s internal weakness, Byzantine military strategy became anchored on defending and controlling the passes and gorges through the Taurus Mountains. In response to the initial Arab victories the Byzantine Empire was reorganized under a military-territorial basis, with the empire being divided into a number of “themes”. The themes were effectively provinces under direct military control, and have been described by some historians as quasi-feudal as the soldier’s descendants would be tied to the land. Theme armies were made up soldiers who would also farm land owned by the military, in a system somewhat similar to the Bingtuan in Xinjiang, China. Within the themes, mountain passes and defiles were territorial subunits that were literally called “kleisoura” under command of a kleisourarches.

Other than some ruins, not much else from the Kelasuri Wall survives. How the wall was garrisoned, how the military was organized, how logistics were handled and specifically how the soldiers were feed is all a mystery. That being said, we do know the wall had a Greek name and the Greek speaking Byzantine military helped the Abasgians build it. With this information I believe it is safe to speculate the wall’s defenses were organized similar to how a Byzantine theme was, with soldier-farmers who both produced food and manned the defenses. Along with Byzantine weaponry and religion, it is likely the empire’s military arts also spread and influenced the Abasgians. What little we do know is that the Abasgians would recruit Laz people from the south, likely from modern day Adjara and other mountainous regions to garrison the walls. Local Abasgians in the coastal lowlands were too few in number, while people from historic Colchis were considered too physically infirm due to their local climate to handle the mountainous terrain and martial duties. I speculate that the Laz recruits were likely from poor mountainous regions, and were lured to man Abasgian garrisons with promises of steady meals and a place to live. Similar to soldiers in Byzantine themes, the Laz would have worked in shifts garrisoning the wall and working in the fields.

A debate exists as to when the wall was built. Arguments range from the 4th century to the 16th century, as it had been noticed that some embrasures in the fortification were seemingly meant for firearms. Moreover, Italian merchants in the Black Sea wrote of an ongoing construction of a fortified wall in Abkhazia. The most likely answer is that the majority of the wall was built in 6th century. At this time not only was the Eurasian steppe particular unsettled by the rapid expansion of the Turks, but Byzantium was at its pinnacle of power and wealth, and thus well equipped to build such extensive fortifications in a distant frontier. This was also when the Darband wall was upgraded from a mere mud-brick wall to a multi-layered defensive network across modern day southern Dagestan and Azerbaijan. In all likelihood, some forts and walls of the Kelasuri Wall were built as early as the 1st century AD, and similar to the Darband Wall were upgraded in later centuries. What motivated the Sasanians to construct such costly defenses to their north likely also motivated the Byzantines and Abasgians to do likewise. The controversy is likely a result of some segments of the wall falling into disrepair only to be rebuilt or renovated later. This would explain why some forts are seemingly built to accommodate firearms.

Northwards Along the Misimian Branch

From the Kelasuri Wall we move inland up through the Kodori River valley following the Misimian Branch of the Silk Road. In modern times this historic caravan route became known as the “Sukhumi Military Highway” which linked Cherkessk to Sukhumi via the Klukhor Pass. Built in the latter half of the 19th century, meant to improve logistics for Russian armies campaigning against the Ottoman Turks, it became famous for its scenic views and a popular drive for tourists in Soviet times. Examining the Misimian route, we will follow this road northwards. For readers who would like to follow along on a map, my suggestion is to use the site “Mapcarta”: https://mapcarta.com/Abkhazia

From the coast the Sukhumi Military Road goes northwards along the Mochara River before it turns east to the Kodori River. 11 kilometers after passing the Kelasuri Wall, there is the Gerzeul Fortress on a small hill. The fort is 5 kilometers east from the village Merkheul, at the southern entrance of a small ravine that the Machara River passes through. This ravine is called the Gerzeul Pass. The fortress would have commanded the road between the Kelasuri fortifications to the south, and the Tsebelda fortress to the north, which will be discussed shortly. The fortress walls ran about 1 kilometer. Only the remains of a tower, church, and gate remain. The gate is 6 meters tall and the tower about 10 meters tall. The church had art craved on to its foundations, and underneath burials were found. At the north end of the Gerzeul Pass where the rivers Machara and Barial merge is the Patskhar fortress, which is smaller than its southern counterpart. Reportedly in ancient times a tribal people distinct from the Abasgians called the Coraxes lived here. From Patskhar another small fort can be seen, the Shapka fort which is located 3 kilometers further up the Mochara River on the right side. There is not much information on these two forts, Patskhar and Shapka. In all likelihood they are unremarkable and minor.

Tsebelda Fortress

Past the Gerzeul Pass one enters historical Apsilia, centered on Tsebelda. The Apsilians were people different from the Abasgians, and were subordinate to the Kingdom of Lazica at the time of Tsebelda’s construction. The core Apsilian land was a small plateau stretching between the Mochara and Kodori Rivers. Located on this plateau is the fortress Tsebelda, the largest inland fortification in Abkhazia. Built in the 6th century with large Byzantine assistance, it was meant to protect the coastal lowlands from Hunnic and Alan invasions from across the mountains. Some confusion can be had, as the name Tsebelda can also appear in sources as Tibeleos, Tsibile, Tzibile, Tsibilium, or Tsabal, the latter two are regularly seen in Russian sources in particular. Tsebelda’s name possibly comes from John Tzibus, who served as Magister Militum per Armeniam under Emperor Justinian. Sources report of John Tzibus’s involvement with fortress construction elsewhere in Lazica, therefore it is a fair speculation.

For travellers from the coast, the path to Tsebelda ran from the Mochara River before climbing up to ridge, and then crossing through the forest. Afterwards the path entered into a meadowland that lies before the great fortress. The Tsebelda Fortress overlooked the Kodori Valley from 400 meters above the valley floor, occupying two cliffs with the eastern one higher than the other. The main entrance faced westward, on the road to the coast in the opposite direction an attacking force from over the mountains would come. The western side was double walled. The fortress was approximately 75000 meters squared with walls 8 meters thick made of limestone blocks. Near the western entrance there was a tower 16 meters tall, capable of hosting catapults. Inside the fortress there were baths, a small creek, water shortage system in form of a large cistern which could collect rain water, and two churches. Buildings appear to have had pipes, likely an internal plumbing system for water, indicating this was a very sophisticated fortress. Additionally three towers have survived in part.

In one church a cross shaped baptismal cistern was discovered, indicating the Tsebelda fortress was a center of Christian proselytization. Likely political subordination to the authorities at Tsebelda was linked to conversion to Christianity. Further evidence to this hypothesis is that among the burials within the fortress, elongated skulls have been discovered. This practice of elongating skulls was done by both the Huns and the Alans. Two wooden boards were tied to the front and back of an infant’s head pressing together, resulting in an elongated cranial structure. As these bodies were found buried in the fortress and not outside, they were likely allies of the Laz and Byzantines, and their baptism was a ritual submission to both Christ and the Christian Roman Emperor.

The defenses of the Kodori Valley and Tsebelda region were likely structured as a web, where the Tsebelda fortress was the central fortification capable of hosting a large garrison, with smaller satellite forts around it acting as signal posts and lookout points. One such example is the Akhysta fort, located opposite to the Tsebelda fortress to the north on the Akhysta Mountain. A small walled enclosure and remnants of a tower survived to this day, likely a watch tower and a signal post. From here garrison could observe the Kodori valley northwards and other valleys and alert the main force at Tsebelda if needed.

During the 6th century wars between Byzantium and Sasanian Persia, power over Lazica and Tsebelda changed hands several times. In the 520’s Lazica, which had always been a vassal state of Rome, defected to Persia due to a dispute over trade. The Laz king Gubazes II pledged loyalty to the Sasanian Emperor and a pro-Sasanian rebellion broke out in Abasgian. With Apsilia subordinate to the Laz and Abasgians, the Persians were allowed to occupy the region, as well as Tsebelda fortress. It is unclear whether it is a legend or factual history, but a story has the commander of the Persian force which occupied Tsebelda falling madly in love with the wife of the commander of Tsebelda. After his advances were repeatedly rejected he attempted to rape her, which led the fortress commander slaughtering him. The rest of the garrison rose up, killing all the Persians occupying the fortress. With Tsebelda in revolt Apsillia became anti-Persian. Eventually Lazica returned to its pro-Byzantine orientation, and the status of Tsebelda returned to the status quo ante prior to the war. Later in the 8th century the fortress was severely damaged by the Arabs when they passed here while campaigning against the Alans, who were under Khazar vassalage.

Today the fortress ruins are in a state of severe disrepair. The walls are mostly buried underground, in some sections the walls are almost entirely grown over. There has been some maintenance of the site in clearing away overgrowth, but much of it would be easily missed by people passing by if there did not know to look for it or were unaware of the fortress’s existence. This unfortunate state of disrepair is not isolated to Tsebelda, many sites in Abkhazia are equally in ruins. The main problem is that Abkhazia’s flora becomes much wilder and grows in greater volumes in the mountains compared to the coast. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Abkhazia’s de facto independence from Georgia, its isolation from international tourism and general poverty has prevented upkeep of its historical ruins, and especially so for Tsebelda.

Once past Tsebelda, information on the Kodori Valley becomes much sparser. Nearly all written historical sources on Abasgia and the Kodori were written by Byzantines. Regions further inland and more distant from Byzantium were less known and less written about, therefore their history is much more opaque to us today. Additionally, during the 2008 war between Russia and Abkhazia against Georgia, there was fighting in the upper Kodori past Tsebelda. This has also helped leave the region less well known compared to the coast, as tourists and researches were more hesitant in travelling there.

After passing Tsebelda the road goes north, and before entering into the Kodori Valley the road crosses the Amtkel and Jampali Rivers. Directly north of this section of the road is the Apushta Mountain, which hosts a small fortress, likely a mere signal post and a satellite outpost of the main Tsebelda fortress. After entering into the Kodori Valley there are small fortress at Bagada and then at Lata. The Lata fort is on a cliff overlooking the valley, near a waterfall.

Chkhalta Fortress

The last significant fortress on the Misimian Road south of the Klukhor Pass is the Chkhalta Fortress at the convergence of the Kodori and Chkhalta Rivers. This fortress is also known as Chirgs-Abaa locally, or as Tsachar or Sideron by the Greeks. Chkhalta during ancient times was home to the Misimian people, a Georgian people originally from Svaneti to the east. The Misimians lived in the upper reaches of the Kodori Valley and gave this branch of the Silk Road its name. During the 9th century the Shavliani ruling family who came from Chkhalta or somewhere nearby claimed the throne of Abasgia.

From here, the road branches into several different routes that can be taken over the mountains. This meant that for caravans or nomadic invaders from the north, several different routes southwards over the mountains would lead them to Chkhalta, thus it occupies a very strategic point. Unlike other fortresses, Chkhalta does not sit upon a hill or mountaintop and command a high point over the valley, instead it is located at the bottom of the valley on a piece of land surrounded by the two merging rivers. The fortress was possibly the strongpoint of a wall that spanned the entire road and much of valley floor. Originally built either in the 4th or 5th century, the main building had two stories, with a wall about 10 meters tall and a tower 15 meters tall. The structure was mostly made with limestone bricks. Reportedly, during the Arab-Khazar war of 737 which saw an Arab army reach the walls of Anakopia, an Arab force came up the Kodori. They made the ruler of Chkhalta pledged loyalty to the Arabs before crossing the Klukhor Pass to attack the Alans in the North Caucasus. For some time after, the ruler of Chkhalta remained an Arab vassal, possibly indicating a sustained Arab presence in the Kodori, or at the very least the Kodori was closed for Alan and Abasgian caravans.

It seems likely there was at least one other fortress structure on a hill overlooking the valley, likely a signal post while the main fort was located below. This speculation is based upon a local legend which is set at Chkhalta, but only makes reference to a fortress that “sits on a craggy cliff overlooking where the Chkhalta River flows into the Kodori River”, but it could merely be a confusion caused by exaggerating the fortress for dramatic effect or some other mistake. Nevertheless, it is a good tale and deserves to be told.

A man coming from Abasgia on the coast passed a fortress that sits on a craggy cliff overlooking where the Chkhalta River flows into the Kodori River, on a mountain covered in greenery. Below, there was a family in mourning because their son had died. He would regularly go hunting over the mountains around the Kuban River, where one day he spotted a beautiful girl. They fell in love, but the girl was the daughter of the powerful lord and her father refused to marry her to a simple boy, so the young lovers arranged to run off together. They agreed to meet each other at nighttime behind the hill where they had first seen each other. To their misfortune, while the girl was riding away her brother and his retainers were returning from a hunt and spotted her fleeing. They followed her to the meeting place and tried to stop the abduction, but the lovers rode off. The brother and his followers followed them over mountains. Nearing his home village at where the Kodori and Chkhalta rivers merge the boy’s horse was killed from under him. The boy was a strong swimmer so he grabbed the girl and carried her across the river, climbed up the mountain and just outside the gates of Chkhalta fortress he was killed by an arrow. With her lover dead and not wanting to be returned to her family, the girl jumped off the cliff into the Kodori to her death.

The Chkhalta Fortress was also central to a famous anecdotal story about the Byzantine Emperor Leo III “the Isaurian”. He is remembered not only for successfully leading the defense of Constantinople from the Arabs in 717, but also infamously initiating the Iconoclasm at the imperial level, receiving the informal epithets of “Saracen minded” and “destroyer of images”. Before Leo was emperor, he sent on a diplomatic mission to the Alans in order to stir them against the Lazica and Iberians who were under Arab control at the time. Leo passed through the land of the Apsilians at Tsebelda, travelled through the Kodori Valley before crossing over the Caucasus to the Alans. The plan was for Leo to set out, followed by a party bringing gold that would be used to pay the Alans to attack the Arabs. For reasons not explained in the sources, the reigning Emperor Justinian II wanted to get rid of Leo, so he never dispatched the promised gold. Additionally those within the Abasgian court who favored the Arabs sent word to the Alans that Leo had been sent to help overthrow their king and cause havoc among their people, and that the Alans should arrest him and hand him over the Abasgians.

Leo managed to convince the Alans that the Abasgians were lying. He also told the Alans that the Abasgians had recently acquired a large amount of gold from Constantinople and it would be most profitable to raid them and seize this great treasure for themselves. Leo and the Alans came up with a plan where the Alans would hand Leo over to the Abasgians and then secretly follow them over the mountains, observing which route they took to see the least defended route. A host of Alani cavalry caught up with Leo and his captors, and then attacked the Apsillians, who were subordinate to the Abasgians. At the same time, a Byzantine army was besieging the capital of Lazica, Archaiopolis in central Colchis when an Arab army arrived to help their vassals. The Byzantine army was forced to retreat, but some 200 men who had been sent north into the Caucasus foothills to scout and scavage for supplies were left behind. Seeing no way to reunite with their army as the Arab force stood between them, they decided to stay put and hide away in the mountains until an opportunity arrived where they could return to Byzantium safety. The Alans received word of the Byzantine soldiers from the Apsilians and helped Leo reach them.

By this time the court fraction who favored Byzantium gained power in Sebastopolis and the Abasgians changed sides, but some fortresses in the mountains were still loyal to the Arabs, including Sideron (Chkhalta). Leo promised Marinus, the leader of the Apsilians, friendship with Constantinople and received 300 warriors from him. They approached Sideron and laid an ambushed. They waited for the soldiers garrisoning the fortress to go outside and work in the fields. When they were least excepting it, Leo with the 200 Byzantines and the 300 Apsillians attacked and captured the soldiers. The fortress’s commander Pharasmanios was still inside, and seeing most of his men captured, surrendered the fort and submitted to the Byzantine emperor. Leo and the 200 Roman soldiers travelled down to Sebastopolis, and from there they took a ship to Trebizond, eventually reaching their homes.

Over the Caucasus Mountains

After Chkhalta several different routes exist that go over the Caucasus, following branching river valleys. The main route follows the Kodori River up to the village Omarishara where the road turns north up the Gvandra River. After a short distance up the Gvandra the valley divides again, and the road stays on the left hand side, up the Klishi River which takes travellers to the Klukhor Pass, and then down the Teberda River. There are other possible routes from Chkhalta. Following the Chkhalta River northwest takes travelers to several different passes, such as Marukh Pass to the Marukha River, or over the Adange Pass into the upper Bzyp River which holds access to the Kongur Pass to Bolshoi Zelenshuk River Valley, or still further to Tsargekhulir Pass which leads to the Bolshaya Laba River. It seems there were no more fortresses on the upper Chkhalta River. All of these rivers, the Teberda, Marukha, Bolshoi Zelenchuk, and Bolshaya Laba are all tributaries of the Kuban and eventually merge with it downstream in the northern foothills.

One final additional route. Following the Kodori to Omarishara, instead of turning left up the Gvandra, if instead one turns right and goes up the Saken River, they reach the Khida Pass into Svaneti. This pass leads to the Nenskra River, an upper tributary of the Inguri River. Somewhere along the Nenskra was the Bukhloon Fort, likely a small site. From here the road goes north up the Nenskra, over high Caucasus via the Donguz-Orun Pass to the upper Baksan River Valley. Going down the Baksan River one would pass under Mount Elbrus, Europe’s tallest peak. Known to the Greeks as Mount Strobilus, meaning “pinecone”, it was here that Promethus was said to have been chained as punishment for giving fire to mankind. The Baksan would also have been home to the Alans. The Baksan-Nenskra-Inguri route in particular was called the Darin Road. It was somewhere here in Svaneti the Sasanians attempted to ambush and kill Zemarchus, a 6th century Byzantine diplomatic envoy. The attempted assassination of Zemarchus was when he was returning from the Turkic Khaganate where he had concluded a trade agreement for silk and an offensive alliance between Byzantium and the Turks against Persia.

Once past Chkhalta, the upper Kodori becomes very desolate, with very few people other than lone hunters. Travellers in the 19th century wrote that hunters had a secret language amongst themselves, and of bee keepers who produced an intoxicating honey drink. One last fortress exists between Chkhalta and Klukhor. Along the Klishi River is the Klych Fortress, somewhere just past Omarishara. The fortress was located on the left side of the road, it was double walled with a moat and at least two towers. Inside there was also a church. It is possible the theologian Saint Maximus the Confessor is buried here. In the 7th century Saint Maximus was exiled from Byzantium for his opposition to Monthelitism, which was a promoted by the imperial state as a theological compromise between Greek Chalcedonian diophysites and monophysites Christians in Egypt.

At the Klukhor Pass there was a fort called Boukolous by the Greeks. Reportedly it was built by Byzantium but was occupied by the Alans later. There are some indications ancient Greeks had passed this area, or least their material culture was brought there, as a bronze helmet was found buried near the pass. From the pass the road follows the Klukhor River, which eventually merges with the Teberda River and the road descends southward following the river to the lowlands. There are a few small hilltop forts along these rivers, though nothing major.

Khumara Fortress

Located in the lower Teberda Valley between modern Karachayevsk and Cherkessk, Khumara sits on top a mountain plateau that dominates the mouth of the valley from the river’s east side. There was also a secondary fort called the Karakentskaya fortress on a mountain top on the western side, along with fortifications below which would control access to the road. The fortress was likely known as Chemarin to the Khazars and other local peoples. Larger than any fortress in Abkhazia, the Khumara fortress was 20.4 hectares (204,000 meters2) with walls 4-7 meters thick and 10 meters tall. The citadel had a ziggurat-pyramid like structure and was located at the northeast side of the fortress.

Historians believe the site had been occupied since pre-historic times due to it being a naturally defended site, but was expanded into a major fortress by the Alans and/or Khazars, possibly with Byzantine assistance. It was likely constructed in response to Arab attacks, with the aforementioned 737 war being a catalyst. Jewish graves and the ruins of a tabernacle shaped structure indicate the Khumara was occupied by the Khazars, whereas the Teberda Valley was home to the Alans. Nearby, stone slabs were found on the sides of a road opposing each other, one with an image of an anchor and Byzantine cross on the other. These were signs meant to bless travellers, which indicate some sort of Byzantine presence. Later in the 9th century the Byzantines aided the Khazars in building Sarkel, a major fortress on the lower Don River, thus it is fully possible that Khumara was likewise built by the Byzantines.

After the Khumara fortress, the road takes differing directions. At a point further north at modern day at Ust-Dzheguta, the road splits. One branch continues north along the Kuban towards the Don River and Pontic Steppe, while another cuts eastward along the Kislovodsk Depression which would have led to the Khazar capital Atil on the Volga River, and on to Chorasmia and Sogdia.

Most interesting! Thanks.

This was fascinating. Thank you for writing!