On the Path of Progress - Petr Khvorostansky, 1915

Translation about the sedentarization of the Kazakh nomads and their adoption of agriculture

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

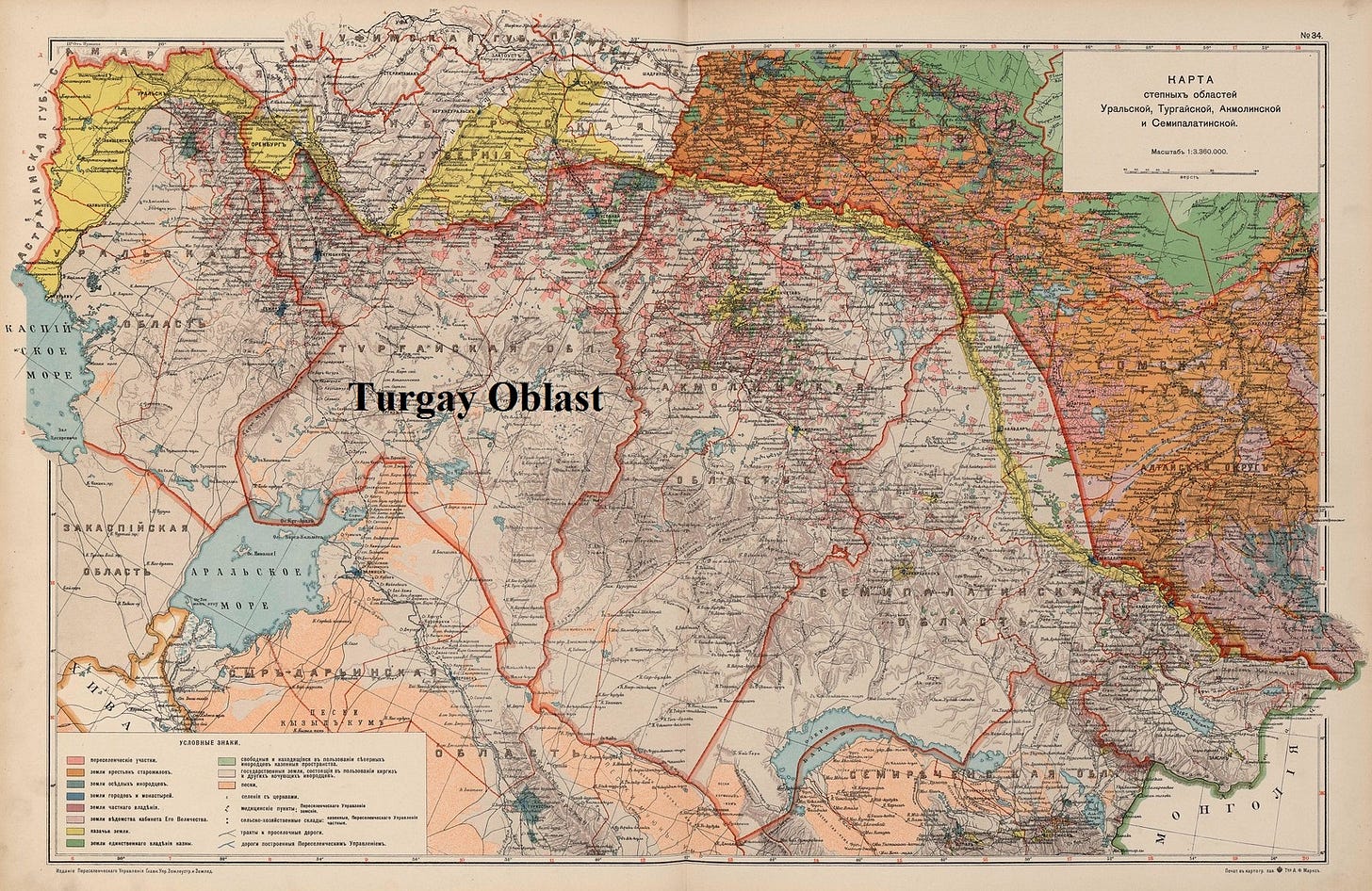

Below is a report discussing the sedentarization of Kazakh nomads and their adoption of agriculture under Russian encouragement. I found almost no information about the author of this text, Petr Andreevich Khvorostansky. Having searched on Yandex, all I found were several other publications by him concerning the development of agriculture on the steppe and similarly related topics. The original title of this report is “The Evolution of the Kyrgyz Economy in the Turgai Oblast” from the journal “Questions of Colonization”, 1915, № 18. The source of this translation can be found here. The original text can be found here.

The Soviet Union is often remembered notoriously for its attempts to forcefully sedentarize the steppe nomads and to turn them into farmers. As can be seen in this report, such efforts were already well underway during the Russian Empire. It can even said that the Soviet efforts in this sphere were merely the continuation of policies already adopted by the Tsarist administration, and that the Soviets simply completed the process.

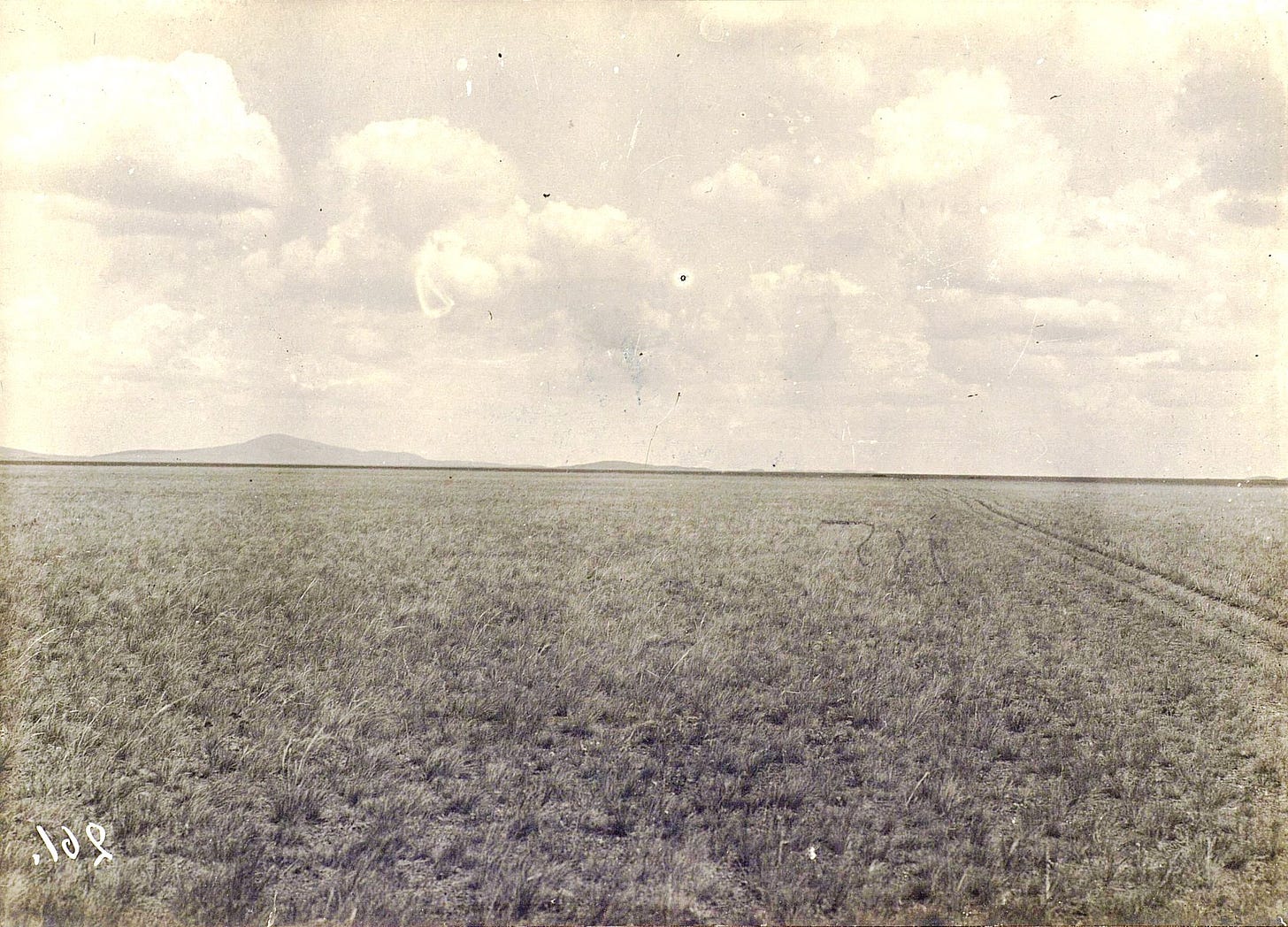

What is particularly interesting, is that it appears that the Russians of the empire had the same incorrect assumptions about pastoral nomadism that the later Soviet Marxists had. Their mistaken belief was that nomadism was simply a more primitive way of life compared to sedentary agriculture, rather than it being an equally complex mode of production and way of life. What they failed to appreciate was that pastoral nomadism, the herding of animals around in the steppe, was a specialization adopted in response to the environmental conditions of the steppe. While the Russians and Soviets were correct in that agriculture and the surplus food supply it produces is a prerequisite for urban life, and by extension necessary for written culture, industrialization and more, what they overlooked is that the ecology of the steppe largely precludes farming due to the land’s aridity, poor soil fertility and other problems.

When agriculture did develop in the steppes historically, it was almost always concentrated in river valleys and occured during periods of stability created by a hegemonic state that could ensure security. Examples of this include the Volga River under the Khazars, the Irtysh and Ili Rivers under the Zungars and Orkhon and Selenga Rivers under the Uyghurs. And these cases the nomads rarely engaged in farming themselves, but instead imported agricultural workers from elsewhere to work the fields. For example, the Khazars imported farmers from the Caucasus and the Zungars imported farmers from the Tarim Basin, the people known today as Uyghurs (different from the medieval Uyghurs on the steppe).

The brief mention of “pure nomads” is also interesting. Owen Lattimore famously said that the “pure nomad was the poor nomad”, as being purely nomadic limited what goods they could produce. For “pure nomads”, their poverty could only be alleviated through trade. Historically, the nomads of what would become the Turgai oblast would likely have been these “pure nomads” and would have mostly traded with the Khiva oasis south of the Aral Sea, who they would have orbited around due to their commerical ties. For more on the divide between steppe and sedentary cultures, I would strongly recommend Lattimore’s writing.

Lastly, it should be noted that prior to the Soviet era, Kazakhs were called Kyrgyz, while modern day Kyrgyz were often called Kara-Kyrgyz (Black Kyrgyz), Wild Stone Kyrgyz, or sometimes as Buruts, after one of the leading Kyrgyz clans.

On the Path of Progress

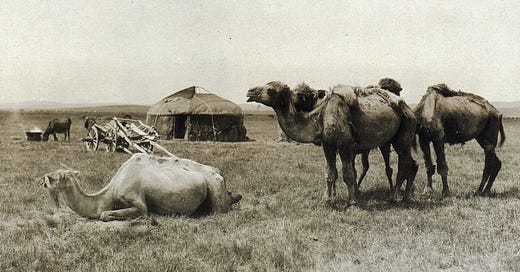

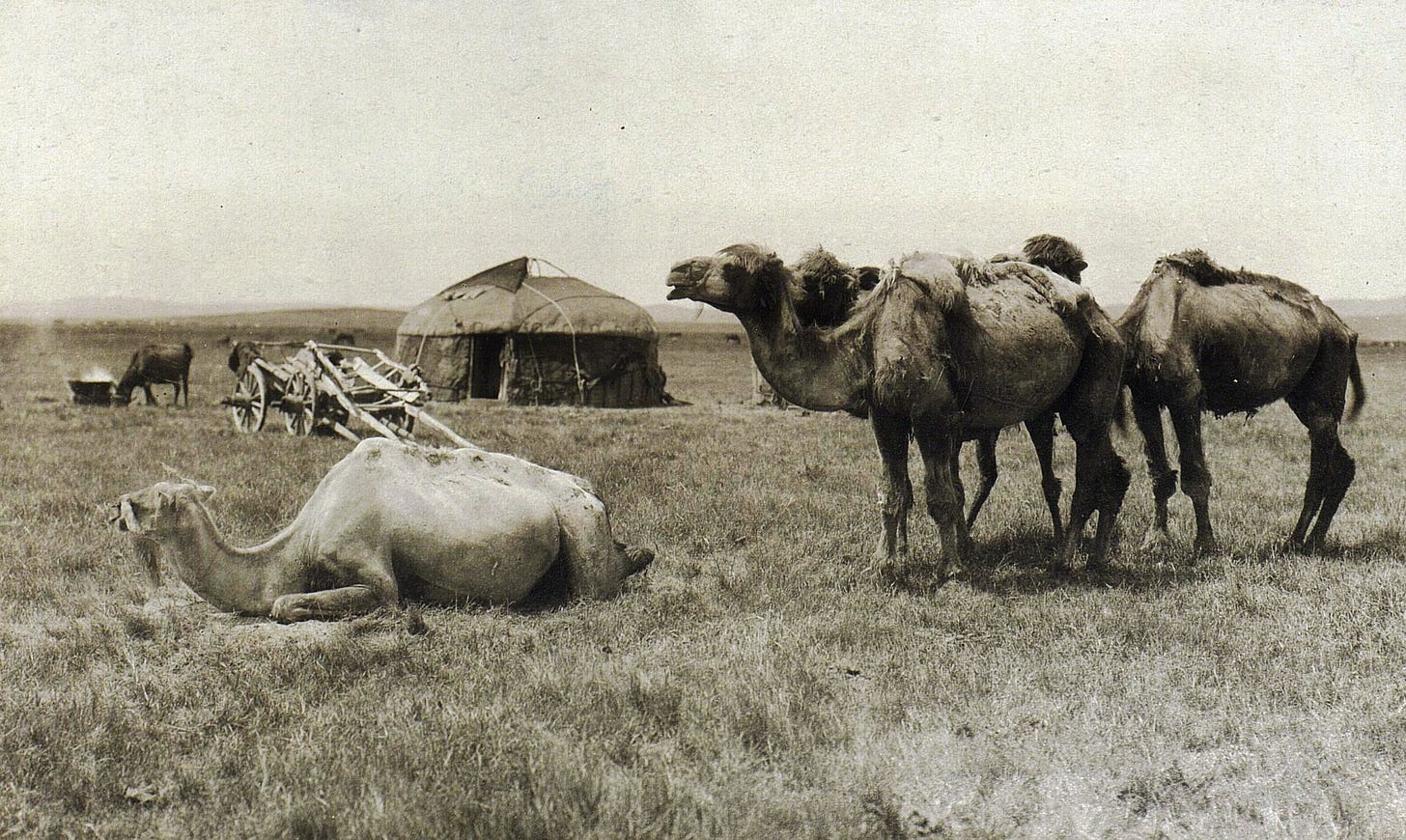

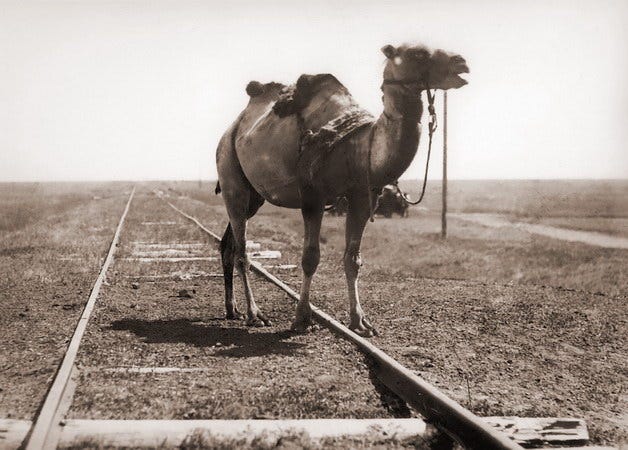

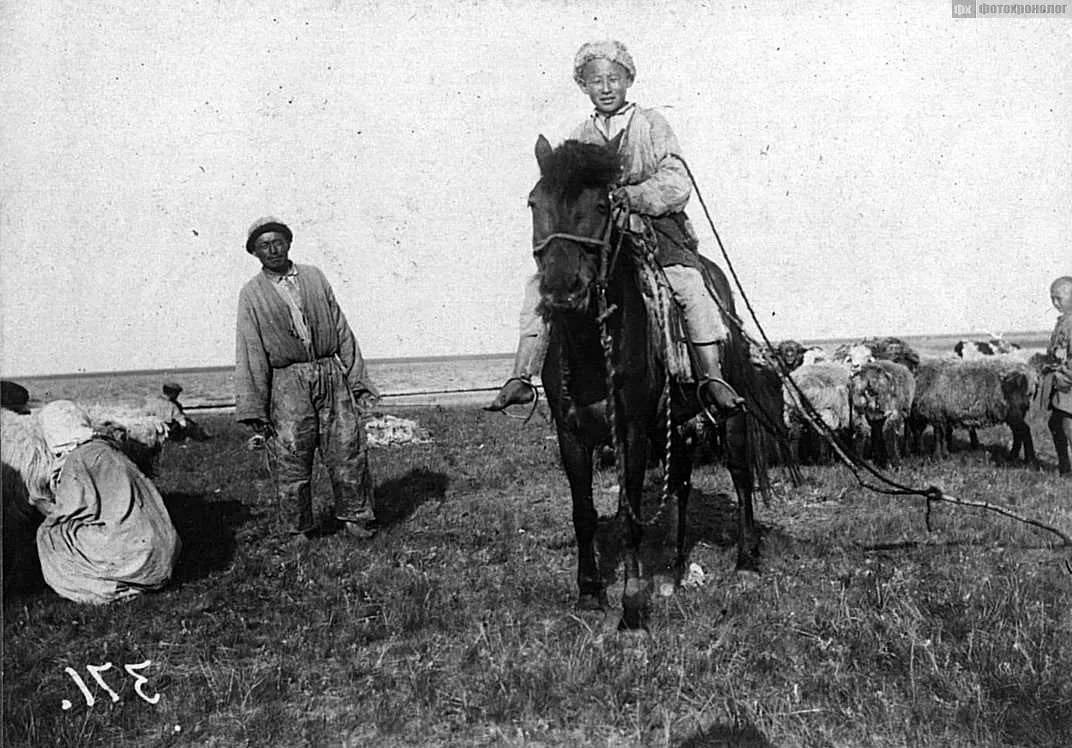

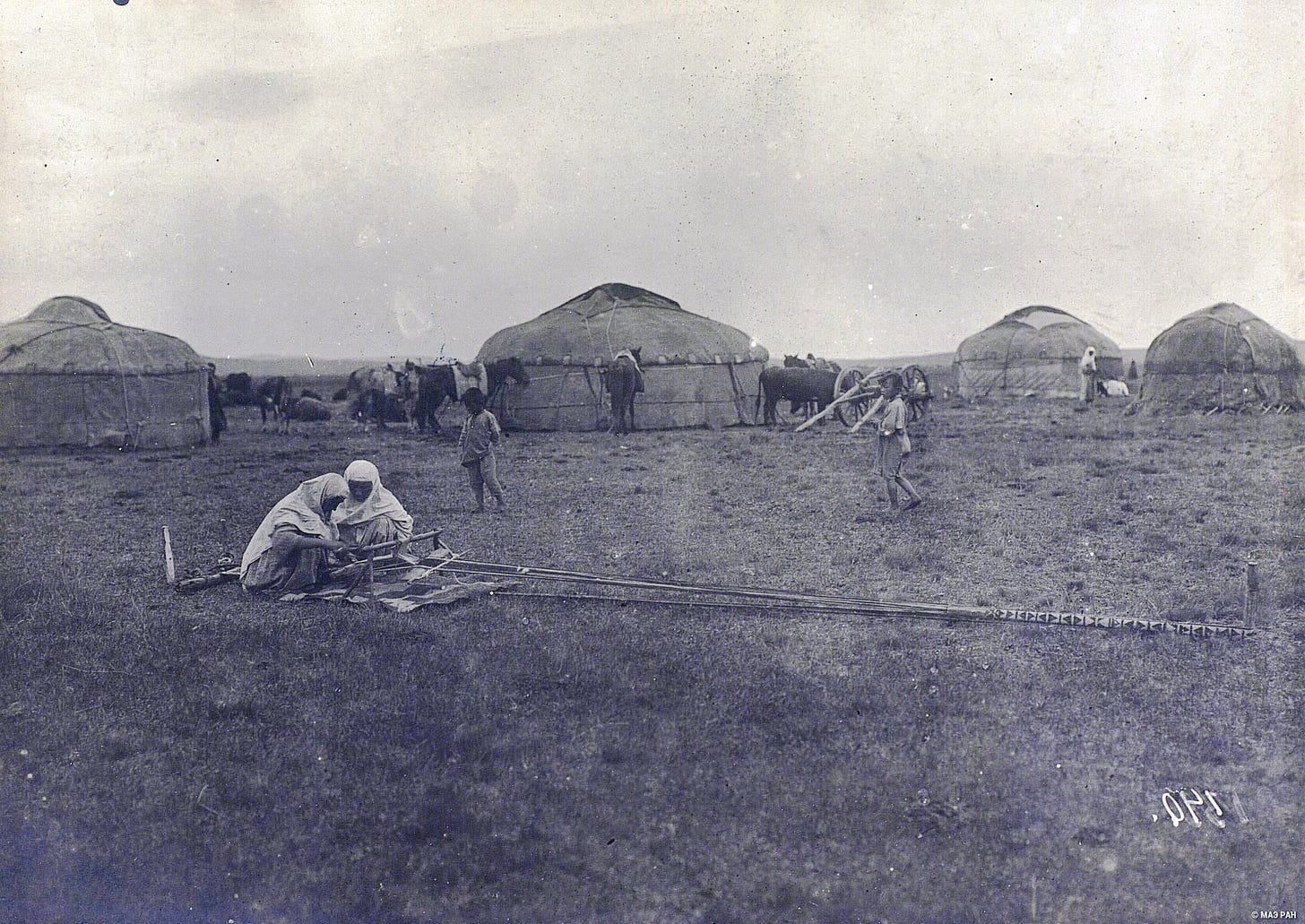

Pure nomads, who during summer and winter months live in mobile homes - felt yurts - moving from place to place with their herds which provide them with everything they need including food, clothing, dwellings, and in extreme cases they can barter their cattle and byproducts for whatever they are in need of. Currently, it might be more difficult to find such pure nomads than it would be to find pure farmers, who are intimately acquainted with factories and the brands of agricultural machinery and tools, and with the exchange prices for grain....

Observing pastoralism and agriculture in different regions of the steppe, as well as between ten year intervals between censuses, we can concluded that the development of agriculture is closely related to the application of human labour, both skilled and unskilled, to agricultural production.

Nomadic pastoralists, who move about with their herds and forage for themselves on free pastures, only apply their labour to products from their herds, which produce food, clothing and dwellings. Those who are sedentary apply the bulk of their labour to preparing feed and housing for their livestock, and food, clothing and dwellings for themselves. Besides what he gets from his herd, the intensive use of a smaller piece of land will bring him a larger amount of benefits for his livelyhood. The use of labour to utilize the natural forces must undoubtedly explain the fact that with a decrease in Kyrgyz land ownership in favour of Russian settlers the welfare of the Kyrgyz has comparatively increased, not decreased. This itself has its limits, perhaps reached by those forms of extensive agriculture which aboriginals borrow from newcomers from Russia. Life, however, does not stand still in place, and in regions where this is economically beneficial, the Kyrgyz in equal measure with Russians settlers, are moving to a more intensive form of agriculture.

Reports by an agronomic organization, for the first year of activity (1913) in the Turgai oblast,1 shows that in the northern volosts2 of the Aktyube and Kustanai uezds,3 where recently the Kyrgyz have been transfered to peasant allotments (15 desyatinas,4 a convenient amount of land for a man). They willingly follow the instructions of the agronomists and instructors, making use of the superior tools, fallow fields, preparing arable land in the autumn for spring crops, sorting seeds, row and stripe farming, grass sowing, etc, generally - improved farming techniques that are useful in the struggle against drought and to achieve the best possible harvest. The reports also note a goal among the Kyrgyz to improve cattle breeding, forming a butter making artel,5 an artel shop, and a credit union. It might be thought that among the Kyrgyz, thanks to close familial connections to groups settled nearby, cooperative movements will encounter more favourable conditions for their growth and strengthening than even among the Russian population.

It would appear that all of the materials given in this article are evidence that life on the Kyrgyz steppe is not frozen in the form of a primitive cattle breeding life, but at least in the north is advancing at an accelerated tempo to the better conditions of a sedentary life. Regrets about the past and concerns for the present and near future, where gloomy pictures of impoverishment and degeneration are often drawn, are caused especially by the unfamiliarity with the steppe and obliviousness of that simply truth, that settlements in the desert and other empty places always and everywhere lead not to the destruction of life, but to their development.