Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of 12 poems by Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov. These poems, as far as I know, have not been translated into English before. The source for these translations is the book “Герой Нашего Времени. Поэмы. Стихотворения.”, Библотека Классической Литературы, Москва, 2017.

Mikhail Lermontov was born in 1814, in Moscow, to the Lermontov family. The Lermontovs traced their origins to George Learmonth, a Scottish adventurer, who entered into service for the Tsardom of Muscovy in 1613, towards the end of Russia’s “Time of Troubles”, a period of prolonged crisis that saw the final collapse of the Rurikid Dynasty, Polish occupation of Moscow, famine and plague. The crisis period came to end with the ascension of the Romanov family, who would rule Russia until 1917. George Learmonth’s name was Russified as Yuri Andreevich Lermont, with his descendants becoming the Lermontovs (the “-ov” ending is genitive plural, meaning “of the Lermonts”).

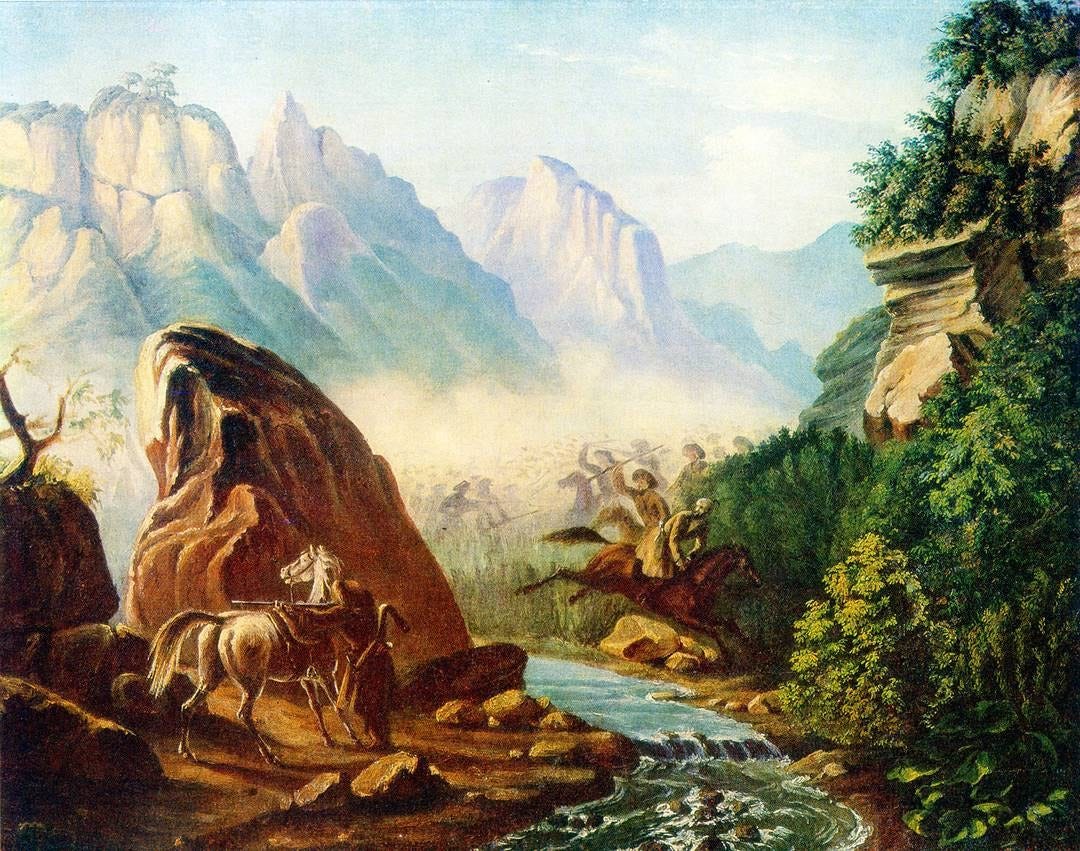

Mikhail Lermontov was first introduced to the Caucasus as child. He suffered from several aliments, which led his grandmother to take him to the mineral spring waters to recover. Lermontov soon became entranced by the picturesque landscapes of the Caucasus Mountains and wild peoples of the region. In time, he developed literary aspirations and joined a Life-Guards Hussar regiment as a junior officer. Upon the death of Alexander Pushkin in 1837, Lermontov wrote a poem which accused the Tsar’s imperial court of conspiring to kill the legendary poet. For this, Lermontov was exiled to the Caucasus.

Russia had first made contact with the Caucasus region centuries prior. In the 10th century, Grand Prince Svyatoslav had raided throughout the region during his wars against the Khazars. Later in the 16th century, with the conquest of the Kazan and Astrakhan Khanates, Russia’s presence in the Caucasus only intensified. Ivan the Terrible had married an Ingush princess, and Cossacks were increasingly settled along the North Caucasus steppes. Towards of end of the 18th century under Catherine the Great, Russia’s penetration of Caucasus deepened further. Russia’s wars against the Ottoman Empire brought it to the defense of Georgia, a fellow Orthodox Christian country in the South Caucasus that was likewise under constant threat by the Muslim Turks. Georgia was soon joined to Russia, and the integration of the Georgian nobility with Russia’s commenced. Soon after, Russia annexed modern day Azerbaijan from Persia.

The annexation of the South Caucasus produced new geopolitical problems for the Russian Empire. All that connected Georgia to Russia was the Daryal Pass, a long trail which cuts a narrow gorge through the high Caucasus. This thin lifeline was under constant threat by the highlanders that lived the mountains, whose wild freedom verged on out-right anarchy. These peoples were not only extremely warlike, and looked down on any labor that did not involve raiding and robbery, they also lived deep in the forests and mountains of the Caucasus, whose natural geography made them all but unconquerable. To quote a Russian general, “The Caucasus may be likened to a mighty fortress, strong by nature, artificially protected by military works, and defended by a numerous garrison. Only thoughtless men would attempt to escalade such a stronghold.” Never before in history had any power conquered the highlanders. But as Russia’s possessions in the South Caucasus remained under threat from the Ottoman Turks and Persia, securing the logistical lifeline became a necessity, and this could only be achieved by outright conquering the highlanders of the North Caucasus.

This effort to conquer the high mountains of the Caucasus resulted in a nearly 60 year long war. While the North Caucasian highlanders never posed the same sort of threat to Russia as did the Turko-Mongols, France, Germany or America, nevertheless they can be fairly said to be one of Russia’s most formidable opponents. The highlanders themselves were very similar to steppe nomads in that they were decentralized, and relied on hit-and-run tactics to slowly bleed out their enemy. And as the quote by the Russian general above states, they had the additional benefit of living within one of the world’s greatest natural fortresses. Every hilltop village was naturally fortified and hardened, every valley offered defenders a chance to ambush invaders, and if defeated, the highlanders could simply retreat deeper into the mountains. The quest to conquer the Caucasus resulted in a grinding war that demanded more and more soldiers in order to win. Many men of the Russian nobility gladly saw this as an opportunity, as war in the Caucasus offered a grand adventure, but others were sent there by force. Similar as Siberia, the Caucasus became a common destination for exiles.

In 1838, upon returning to Petersburg from his exile, Lermontov wrote his most famous work, the novel “Hero of Our Time”, about the adventures of Grigory Pechorin, a nihilistic Russian officer in the Caucasus, and his exploits among both the colonial Russian society and the native Caucasians. The novel is striking for not only its vivid adventures and cynicism, but it was also one of the earliest “psychological” novels, a predecessor to Dostoevsky it could be said.

The character Pechorin was in large part based on Lermontov himself. He soon became bored of society in Petersburg, and in 1840 he provoked in a duel. As punishment, Lermontov was exiled to the Caucasus again, where he fought against the Chechens. Lermontov soon returned to Petersburg, and again was soon bored, so returned back to the Caucasus. In a case of reality imitating art, at the spa town of Pyatigorsk Lermontov began relentlessly teasing his friend Nikolai Solomonovich Martynov for his Grushnitsky-esque, foppish vanity. Martynov challenged Lermontov to a duel, which resulted in Lermontov’s death, in 1841.

Strangely, Mikhail Lermontov remains far less known in the English-speaking world when compared to other 19th century Russian literary titans like Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Turgenev. This is unfortunate, not only because of his work’s quality (Hero of Our Time is the best Russian novel, in my opinion), but also because Lermontov’s paintings, poems and novel help us understand the importance of the Caucasus to Russia.

The Caucasus have always had an out-sized importance to Russian culture as a distant, romantic land that could actually be visited and experienced. The Caucasian highlanders themselves are possibly some of the most formidable peoples in the world, and Russia’s continued ambition to rule them has only served to harden Russians themselves. Unlike other European encounters with the non-European world, Russians rarely identified themselves in opposition to the Caucasians. Instead, Russians became partially Caucasian themselves through the process of conquering and ruling the region. The most famous example of this is of course Joseph Stalin, who, alongside his clique which largely consisted other Caucasians, not only ruled the USSR, but also effectively Russified it, and fully brought Russia into modernity. In more recent times, it was Vladimir Putin’s victory over Chechen separatists that both solidified his power over post-Soviet Russia, and began Russia’s return to Great Power status. It is said that only a Caucasian can conquer the Caucasus. The 2002 film “War” by Alexei Balabanov depicts this dynamic most vividly.

Russians are often thought of as being either northern-east Europeans, Siberians, Asiatic Mongoloids, but few think of them as being of the Caucasus. And Russia can not be properly understood without also understanding the Caucasus. For non-Russians, the works of Mikhail Lermontov are an excellent place to begin with when learning about the Caucasus.

Aside from my own linguistic limitations, poetry is naturally very difficult to translate. Sacrifices are inevitable in terms of rhythm, rhyme, flow, precise use of words, etc. I also had some trouble in formatting. If anyone notices mistakes, or can suggest better use of words, please let me know. Also let me know if you want more poetry translations. Most of Lermontov’s poems remain untranslated.

Poem list: To the Caucasus, Sleep, Morning in the Caucasus, Georgian Song, Caucasus, Kinzhal, View of the Mountain from the Steppes of Kozlov, Cherkeshenka, Gifts of the Terek, Spring, In the Northern Wilds Standing Alone, The Cliff

To the Caucasus, 1830 (Кавказу на Русском)

Caucasus! Distant country! Home to simple liberties! And you full of unhappiness And bloodied by war!.. Such caves and cliffs Under a wild veil of mist To hear also cries of passion, Sounds of glory, gold and chains?.. No! Past years are forgotten, Cherkes, in your fatherland: Freedom of a formerly dear land They perish with fame for her.

Sleep (In the midday heat in a valley of Dagestan), 1841 (Сон на Русском)

In the midday heat in a valley of Dagestan With lead in my chest lying motionless I; Deep wound smoking still, Drop by drop my blood struggles. I lied alone on the sand of the valley; Ledges of cliff crowded around, And the sun burned their yellow peaks And it burned me - but I slept with a lifeless slumber. And I dreamed of shining lights An evening feast on the native side. Between young wives, crowned with flowers, A fun conversation about me. But the cheerful conversation goes without me, I sat there deep in thought and alone, And in a sad dream her young soul God knows what was immersed; And I dreamed of her in a valley of Dagestan; A familiar body lying in this valley; In his chest, a smoking, blackened wound, And blood poured out in a cold stream.

Morning in the Caucasus, 1830 (Утро на Кавказ на Русском)

Daybreak – the wind blows a wild veil Around the wooded mountains fog is like night; Silence at the feet of the Caucasus; A silent herd, a river murmurs alone. Here in the cliffs a newborn ray Its bursts out suddenly, cutting through the clouds, And pink along the river and tents Spilled brilliance, that shines there and there: As girls bath in the shadows, When they see a young man, All blush, averting their gaze to the ground: But how to run away, if the dear thief is so close by!..

Georgian Song, 1829 (Грузинская Песня на Русском)

There lived a Georgian girl,

Withering in a stuffy harem;

It occurred once:

From black eyes

Diamond of love, sorrow for her son,

It rolled out:

Ah, her old Armenian

Proud!...

Around her are crystals, rubies;

But how not to cry from the grief

About her old man?

His hand

Caresses the girl the whole day:

And what more? –

Her beauty hides like a shadow.

Oh god!...

He fears betrayal.

His high, strong walls;

But all love

Despised. Again

Blush on cheeks alive

She appeared.

And sometimes a pearl between her eyelashes.

Without a fight…

But the Armenian showed insidiousness,

Betrayal and ingratitude

How it changes!

Chagrin, revenge,

For the first time it was only him

He realized!

And the waves of criminal corpses

His betrayal.Caucasus, 1830 (Кавказ на Русском)

Although I fated at the dawn of my days,

O southern mountains, so distant from you,

So forever their memory, you must be there one time:

Like a sweet song of my homeland,

Caucasus I love.

In infant years I lost my mother.

But I imagined in the pink evening hour

The steppe repeated to me a memorable voice.

For this I love the peaks of those cliffs,

Caucasus I love.

I was happy with you, in the gorges of the mountains,

Five years flashed by: all yearning for you.

There I saw a pair of divine eyes;

And the heart leaps, remembering that sight:

Caucasus I love!...Kinzhal, 1838 (Кинжал на Русском) (A kinzhal is a dagger commonly used by Caucasians. The word is originally Persian, and was adopted into Russian)

I love you, my damask kinzhal, Shining and cold comrade. The pensive Georgian forged you for revenge, For a terrible battle that sharpened Cherkess freedom. A lily’s hand brought you to me As a sign of memory, at the moment of parting, And the first time blood did not flow down you, But a bright tear – a pearl of suffering. And black eyes, stopping on me, Full of a secret sadness, Like steel you quiver in fire, Then it fades, then it sparkles. Given to me as a companion, a silent pledge of love, And the wanderer in you is not without example: Yes, I will not change and I will harden my soul, As you, as you, my iron friend.

View of the Mountain from the Steppes of Kozlov, 1838 (Вид Гор из Степей Козлова на Русском) (Unlike the other poems set in the Caucasus, this is set in Crimea)

Pilgrim

Is Allah there in the heart of the desert

Frozen waves raised up like a stronghold,

Dens with your angels;

Or Divas, with fatal words,

With walls of such heights

A mass of rocks piled up.

So the way north is barricaded

To the stars, wandering from the east?

That the entire sky is alight:

Is it not the fire of Tsargrad?

Or god nailed to the ceiling vaults

You, midnight lamp,

Lighthouse savior, joy

Illumination floating across the sea?

Mirza

There was I, there, from the day of creation,

A raging eternal bizzard;

Potokov saw the craddle.

He perished, and the steam of his breath froze.

I paved my bold trail,

Where there are no roads for eagles,

And thunder slumbers over its depths,

And there, where over my turban

Only one star sparkles,

Then Chatyr-dag was…

Pilgrim

A!..Cherkeshenka, 1829 (Черкешенка на Русском) (Cherkeshenka is a way of saying a female Circassian, which are often said to be the most beautiful of women)

I saw you: hills and fields, Bushes of the all the mountains, Happy people of the silent steppes, And quiet simple manners! But there, where the Terek flows, Cherkeshenka, I saw, - The gaze of a maidan’s heart chained; And thoughts involuntarily fly away To roam among the lovely, distant cliffs… So, the spirit of remorse, Hearing heavenly sounds, flies off Behold a still more heavenly sight: So a moan of love, passions and torture Before the grave in memory sounds.

Gifts of the Terek, 1839 (Дары Терек на Русском)

The Terek howls, wild and vicious, Between the masses of rocks, His cry is like a storm, Its tears fly and spray. But, across the steppe it runs, He slyly accept the view And, friendly caressing, To the Caspian Sea it murmurs: “Make way, o old sea, Give me shelter in your waves! Walking in the open, It is time for my rest. I was born near Kazbek, Nurtured on the breasts of the clouds, With a power alien to man Eternally prepared to contest. I, with your sons head into our fun, Ruined native Daryal And of its scattered boulders, to its glory, He drove the entire herd”. But, bowing down to the gentle shore, The Caspian subsided, as if it was asleep, And again, caressing, the Terek Murmurs in the old man’s ear: “I brought you a gift! That present is not simple: From the field of battle a Kabardian, The daring Kabardian. Him in his precious chain mail, In steel elbowpads: From the sacred verses of the Koran Written in gold by him. He furrowed his brows, And the edges of his mustache Stained by sultry blood A noble mark; An open view, meekly, Full of old enmity; Cherished forelock on the back of the head Blows into the black cosmos”. But bowing down to the gentle shore, The Caspian dormant and silent; And, worrying, the wild Terek Says to the old man again: “Listen, uncle, a priceless gift! That others all are our gifts? But from its entire universe I hid until now. I rushed to you like waves The dead body of a young Cossack, With dark-pale shoulders, With a light-brown braid. Her sad misty face, A gaze so quiet, sweet sleep, And on the chest from a small wound A trickle of scarlet runs. The beauty of youth Doesn’t yearn over the river Only one in all the villages Of the Grebensky Cossacks. I saddled my stallion, And in the mountain, in a night battle, On the kinzhal of an evil Chechen Lays down their head”. The angry stream fell silent, And over him, white as snow, Head obscured by the braid, Swaying. And the old man in a splendor of power Got up, mighty, like a thunderstorm, And dressed wet in passion Dark-blue eyes. He jumped, full of fun, And in their embrace The oncoming waves Accepted with a murmur of love.

Spring, 1830 (Весна на Русском)

When the ice breaks in spring With a river excitedly flowing, When among the fields Black naked earth And mist lies down from among the clouds On freshly tiled fields, - An evil dreams nourishes on sadness In my inexperienced soul; I see, nature becoming younger, But to be younger only for her; A scarlet flame of calm cheeks Taking away time with you, And this, who so suffered, so much, Love for her in the heart will not be found.

In the Northern Wilds Standing Alone, 1841 (На Севере Диком Стоит Одинок на Русском)

In the northern wilds standing alone

On the naked peak of a pine

And in a slumber, swinging, and snow falling

Dressed, like a robe, her.

And she dreams of everything, that in a wilderness far away,

In that frontier, where the sun rises,

Alone and sad, on a cliff with unlit fire

A beautiful palm tree grows.The Cliff, 1841 (Утес на Русском)

A golden cloud camped at night On the chest of a giant-cliff; In morning she sped off early on her way, Playing merrily across the azure; But there remained a wet mark in the wrinkle Of the old cliff. Alone He stood, deep in thought, And quietly crying in the wilderness.

Loved this. I for one would enjoy more poetry translations. Also, bold call to name Hero of Our Time as the best Russian novel! Do you have a particular translation you’d recommend?

"Sleep" is usually translated as "The Dream" in English.

In noon's heat, in a dale of Dagestan

With lead inside my breast, stirless I lay;

The deep wound still smoked on; my blood

Kept trickling drop by drop away.

On the dale's sand alone I lay. The cliffs

Crowded around in ledges steep,

And the sun scorched their tawny tops

And scorched me — but I slept death's sleep.

And in a dream I saw an evening feast

That in my native land with bright lights shone;

Among young women crowned with flowers,

A merry talk concerning me went on.

But in the merry talk not joining,

One of them sat there lost in thought,

And in a melancholy dream

Her young soul was immersed — God knows by what.

And of a dale in Dagestan she dreamt;

In that dale lay the corpse of one she knew;

Within his breast a smoking wound showed black,

And blood ran in a stream that colder grew.

One of my favourite poems. No idea Lermontov was a painter as well, thanks for putting together this piece.