Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Nomads, The Steppe and the Caucasus

The devastation inflicted by steppe nomads upon the agricultural societies to their south is one of the great stories in Eurasian history. Attila the Hun’s campaigns against Rome and Mongol invasions of China are familiar to us all, so is China’s famous Great Wall which was built to protect civilization from the barbarians to the north. Far less known is that similar “Great Walls” were built all across Eurasia. China was not alone as a victim of nomadic predation. Steppe lands stretch from the frontiers of China in the east to Ukraine in the west, and just as Xiongnu and Mongols terrorized China, Huns and Turks terrorized those in the west. After the Great Walls of China, the next most significant set of walls were located in the Caucasus Mountains.

The Caucasus region functions as a land bridge that connects the Eurasian steppes with Persia and the Middle East in the south. For the nomads that roamed the steppe for thousands of years the Caucasus was one of the quickest and easiest roads leading to settled peoples in the south. Central Asia, by contrast, has vast stretches of desert wastelands and high mountains sparsely populated, making any nomadic raid over these lands long and arduous. Only the route down through the eastern Balkans compares to the Caucasus in this regard. From the rich grasslands north of the Caucasus, nomads could rapidly pass the mountains, terrorize the settled cultures of the south whom they would raid and pillage before returning home. Yet, the settled peoples to the south of the Caucasus were not entirely defenseless. There are about 80 mountain passes over the Caucasus but nearly all would require navigating through some of the most difficult terrain and people in the world. The Caucasus are a formidable mountain chain, a labyrinth of valleys and precipices, and home to peoples who would savagely defended themselves from all invaders. As the Russian Imperial General A.A. Veliaminov said, "The Caucasus may be likened to a mighty fortress, marvelously strong”. A nomadic horde had only two ideal options in crossing the Caucasus, either the Daryal Pass or the Caspian Gates at modern Derbent.

The Caspian Gate offered the nomads a much more convenient route around the mountains. From the rich pastoral lands in the North Caucasus the steppe narrows to a mere dozen kilometers in width between the mountains and the Caspian Sea and continues southwards. The wide expanse of the steppe lands becomes a corridor, a narrow lowland strip running through modern Dagestan and into Azerbaijan unabated. The only significant change being an increase in aridity during the approaches to modern Makhachkala. Much of Azerbaijan is effectively a small south pocket of steppe narrowly connected to the rest of Eurasian steppe, similar to Pannonia in Europe. Not by accident is Azerbaijan a Turkic speaking country. Its land was perfectly suited for the pastoral grazing providing the nomadic Turks a home, from where they slowly Turkicized the surrounding people over the centuries. Looking at the region more broadly, the corridor links the Eurasian steppe world to Persia and the Middle East. A nomadic host could travel from the steppe reaching the south in just a few days, an immensely easier trip than crossing the high Caucasus or the Kyzylkum or Karakum Deserts in Central Asia.

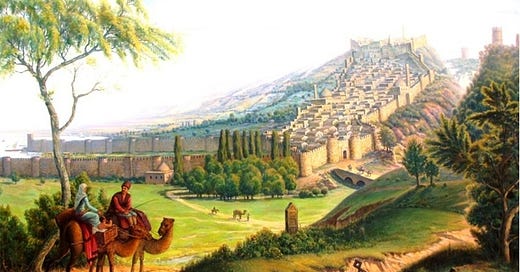

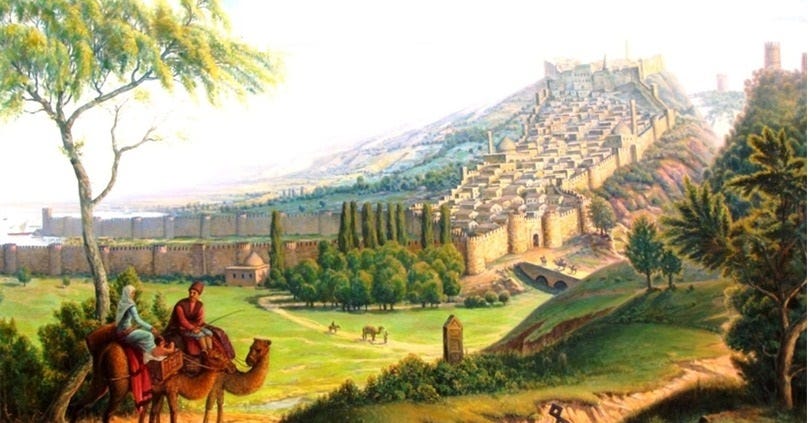

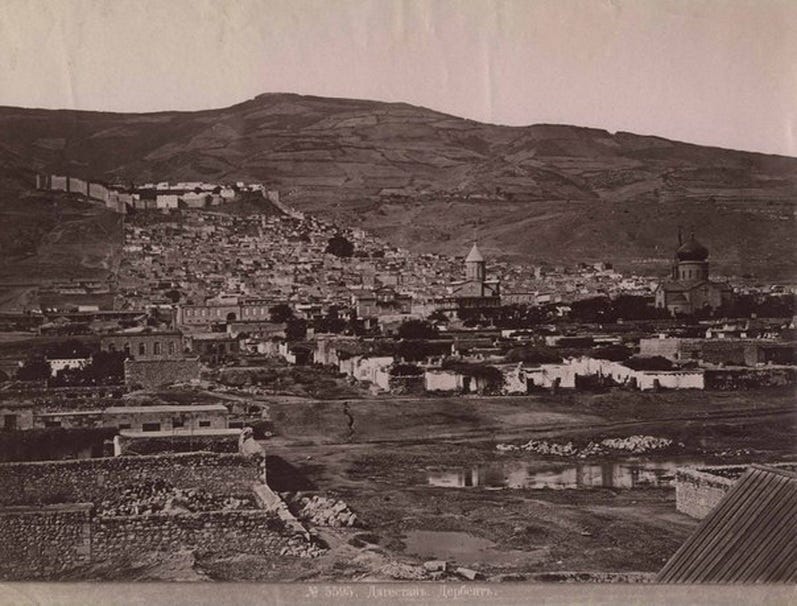

This lowland corridor was a natural invasion route for the nomads. In order to stop the steppe nomads from using this route, successive empires built fortified walls between the mountains and the sea. The fortress and walls of Derbent were built at the southern end of this corridor, which artificially expanded the inaccessibility of the mountains up to the sea. It remained one of the most important locations in Eurasian history, including up until today. For millennium it was regarded as the northern most edge of the civilized world, an outpost on a distant frontier that held at bay the apocalyptic force that was the steppe nomads. Located at the narrowest point on the lowland corridor, where the distance from the fortress overlooking the city to the sea is only 3 km, the walls of Derbent were built to regulate north-south movement between these two worlds. There were two addition walls located further south combined with fortresses and hilltop watch towers. This long narrow corridor was known as the “Caspian Gates”. Historically, control over the Caspian Gates held a similar degree of importance to the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca or the Panama and Suez Canals today. Control over these choke points today grants power to decide the fate of nations and even the world.

Today, Derbent is located in Russia, in the Republic of Dagestan. It is Russia’s oldest city and its most southern. It is also home to one of the world’s oldest mosques, the Juma Mosque, which was originally built in 733. The name Derbent comes from the Persian word “Darband”, meaning gate. Later the Arabs would call it “Bab al-Abwab”, or “the Gate of Gates”. The modern fortress is today called “Naryn-Kala”.

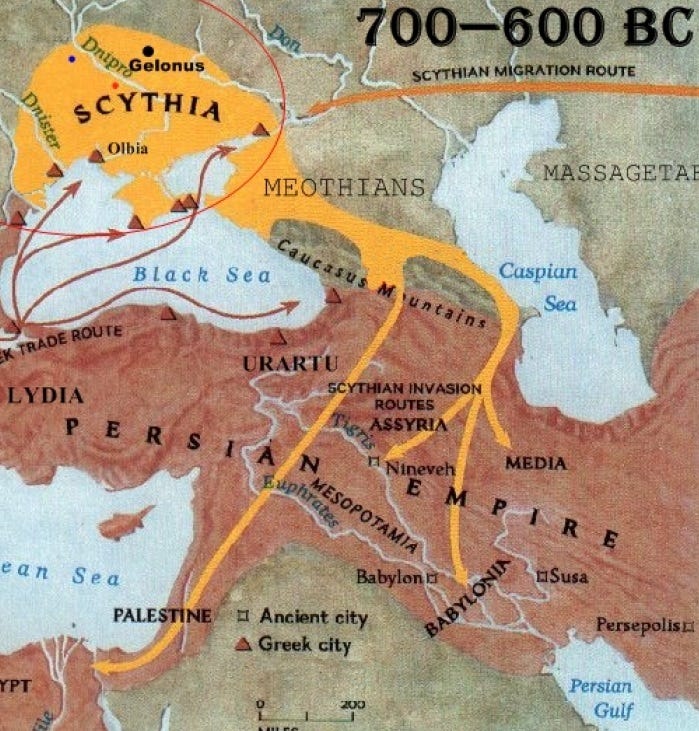

The first recorded nomadic invasion that passed through the Caspian Gates was in the 7th century BC. According to the first Greek historian Herodotus, the Cimmerians fled south over the Caucasus from the Scythians, both Iranic nomads from the Pontic Steppe (modern day Ukraine). The Cimmerians rode passed over the western Caucasus Mountains and the Scythians, in pursuit, chased them by passing through the Caspian Gates. After the Caspian Gates, the Scythians occupied Caucasian Albania (called Arran in the early Middle Ages, and now Azerbaijan) and Media for 28 years. From here the Scythians conducted raids across the region as far as the Levant and played a role in tearing down the Assyrian Empire. Scythian power was eventually overthrown by the Medes and they retreated northwards back to the Steppe, while some Scythians remained and assimilated into the local population. Nomads themselves left almost no written records and there is a general scarcity of written records from this time, however it is fair to assume this Scythian invasion was neither the first nor the only nomads who passed through the Caspian Gates. Instead, this Scythian invasion was likely particularly noteworthy and eventful, and thus survived in memory long enough for Herodotus to write of it two centuries later.

History of the Caspian Gates for the next several centuries is sparsely known. According to legends written in the various versions of the “Alexander Romance”, Alexander the Great campaigned here during his conquest of the Persian Empire. In some traditions, Alexander advanced north of the mountains before turning back, but the common story involves Alexander himself building both the wall at Derbent and in the Daryal Pass in order to block the barbarian tribes of Gog and Magog from invading the civilized world, a topic discussed in greater detail later on. Other legends say Alexander only built the wall in Daryal because the water level of the Caspian Sea was much higher in ancient times, therefore no need for a wall as it was naturally impassable. In the 1st century BC the Roman general Pompey campaigned across the South Caucasus during his pursuit of Mithridates Eupator, bringing Colchis, Iberia (modern day eastern Georgia), and Albania under Roman dominion. It is unknown what Pompey did in relation to the Caspian Gates and the nomads to the north, but what we do know is that he marched as far as the shores of the Caspian Sea. Pompey thought of himself as a new Alexander, another great conqueror who brought the east under his specter. It is said upon reaching the Caspian, Pompey considered marching deeper into Asia, to conquer Persia and then India just as Alexander had done two centuries earlier. According Strabo and Pliny, Pompey instead decided to turn back after encountering spiders whose bites would cause soldiers to laugh themselves to death and snakes that could swallow oxen whole, but this is likely a cover for different reasons.

Limes Caspius

Derbent remained a minor town in Caucasian Albania until the 4th century AD when it was transformed by the Sasanian Persian Empire into the great fortification it is remembered as. In 387 AD, the South Caucasus was brought under Sasanian dominion which coincided with a revolution in the Eurasia steppes. This was the emergence of the Huns into world history. Possibly a proto-Turkic people descendant from the Xiongnu, the Huns were followed by the Turks in later centuries. The Huns migrated westward across the steppe, and somewhere near the Urals or on the Pontic Steppe they split into two groups. One went west into Europe, becoming famed for their ruler Attila and helping tear down the Western Roman Empire, while the other group migrated into the North Caucasus from where they raided south. Both Huns and later Turks were much more aggressive than their Iranic predecessors which led the Sasanians to construct their major defensive works in the Caucasus.

The walls of Derbent were originally expanded into a major fortified installation to guard the frontier under the reign of Shah Yezdigerd II during the middle of the 5th century. Under Shah Yezdigerd II, the Derbent defenses were merely a mud-brick wall, several meters thick and likely around 16 meters tall. Shah Khosrov Anushirvan during the 6th century further expanded the Derbent fortifications and built additional fortifications to its south. Derbent was double walled, both being about 4 meters thick, 18-20 meters tall, and 350-400 meters apart. Based on archaeological excavations from the 1970’s, the original wall was mud-brick while the expanded wall was made of stone and was built on top of the original. With the 6th century additions there were 7 gates, 72 towers on the northern wall 27 towers on the southern wall. Both walls ran about 3500 meters from the shore up to the citadel on the hilltop overlooking the pass. Additionally, a wall was built from the citadel which stretched 45 km westward inland into the mountains. This wall connected several forts and watchtowers that were strategically placed to guard against anyone attempting to outflank the Derbent pass. In Derbent itself, the citadel sat on the hill top giving it a commanding view of the town and Caspian coast as far as the eye could see in both directions. In recent centuries much of the town was enclosed within the two walls, but it is unclear exactly was the layout during the Sasanian period and later. Additionally there was the Toprak-Kala fortress 20 km south of Derbent, a large fortress on the lowlands encircled by a ditch. It is thought site housed 10,000 horsemen and an additional 20,000 infantry (not to be confused with much more famous site in Uzbekistan’s Khiva oasis).

To the south were additional layers of defensive fortifications. There were two more wall systems; the Ghilchilchay wall and the Besh-Barmak Wall further south. The Ghilghilchay wall was about 140 km south of Derbent, located at modern Gil-Gil Cay, Azerbaijan. The wall was likely constructed around the same time as Derbent’s first wall as it is similarly made of mud-bricks. The wall ran 60 km from the coast up into the mountains to the west, just as the Derbent wall. Its height ranged from 4-6 meters tall with 135 towers, each approximately 8 meters tall. The mud bricks were made on site and their production resulted in the creation of a ditch to the wall’s north. The local river ran in a zig-zag course and was used to bolster the wall’s defenses. When the river ran to the north of the wall it added an additional obstacle to attackers. Where the river ran to the south of the wall, at elevated points on the river’s southern bank additional forts were constructed. The wall was integrated with forts and barracks that had gates, but it seems most civilian traffic was guided through gaps in the wall, presumably these gaps could be blocked if under attack. The wall extended into the mountains up to the Chiraq-Kala fort, an inaccessible hilltop lookout and signal post. Chiraq-Kala overlooked the Ghilghilchay wall and much of the Caspian coast. During an attack by the Huns or Turks the garrison here could light the beacon and alert forces further south to prepare for an attack.

The final wall was the Besh-Barmak Wall (not to be confused with the Central Asian cuisine), located only 30 km south of the Ghilghilchay wall. The wall spanned the entire plain from the sea up to a hilltop castle located on the toe of the southeastern most spur of the Caucasus. The distance between the mountains and the sea is very narrow here, the wall was likely only 3-4 km long.

These three walls and adjoining hilltop forts constitute the Caspian Gates, a series of limes meant to halt, or at the very least, slow down any attack by steppe nomads coming from the north. Yet, these walls could be successfully penetrated by nomads and if they came under heavy attack reinforcements would be required. In order to ensure the nomads could not penetrate further into imperial territories, the Sasanians established additional fortresses and stationed forces across the plains of Caucasian Albania, allowing them to quickly react if a nomadic force broke through the Caspian Gates. The main fortress towns were Tiflis, (modern Tbilisi, capital of Georgia), Ganja and Perozapat (modern Barda). Other forces were stationed along the modern day Kura River which flows eastward across Albania in the Caspian, and still more scattered across the Mughan Steppe in southern Azerbaijan and northern Iran, blocking access to ancient Armenia and Media. Immense infrastructural improvements were required in order to feed and supply all the Sasanian garrisons in the region. Irrigation, canals, and agriculture were all labor intensive projects, and thus the imperial state relocated people to this frontier in order to supply labor.

If the nomads succeeded in breaking through Derbent and the two additional walls, the Sasanian strategy to defending its Caucasus frontier was what is called “Defense in Depth”, where defensive positions are not a single line, but a web. Not an unbendable steel barrier but an elastic, multi-layered network of fortifications meant to slow down any invader. With the invader’s progress slowed, the Sasanians would have time to bring up additional forces which could be brought to bear against the nomads and them destroy them. As will be seen further, Derbent was not impenetrable.

As mentioned before, the creation of the Caspian Gates was triggered by the arrival of the Huns to western Eurasia. They first penetrated south of the Caucasus in 395-396 AD and again in 441, while simultaneously the European Huns were launching incursions into the Balkan, Italian and Gaulic provinces of the Roman Empire. Despite centuries of conflict between these two ancient empires, the Romans and Sasanians recognized the Huns to be a uniquely dangerous threat that plagued them both and put aside their differences for the time being to cooperate. The Roman Emperor Theodosius II and Persian Shah Yazdigerd I signed an alliance treaty in 408 agreeing to cooperate in defending the Caucasian passes. Sasanian Persia was to garrison the fortifications but Rome was to pay for half of the cost, 160 Kilograms of gold annually. Later during the Islamic period plates were found within the old Derbent walls which accredited the Romans for helping to build the fortifications. This alliance began to fall apart during the early 6th century. By the reign of Justin II in 560’s Rome was actively seeking an offensive alliance with the Turkic Khaganate against Sasanian Persia.

Rise of the Khazars and the Caliphate

A century of peace between Rome and Persia was broken under the reign of Emperor Anastasius I during the early 6th century, inaugurating a near century long war between the two empires. In a series of wars akin to the 100 Years between England and France, they culminated with a geopolitical revolution in western Eurasia, marking the concurrent rise of the Khazar Turks and the rise of Islam.

The final Roman/Byzantine-Sasanian war was most dramatic of them. It saw the total collapse of Roman power in the east and Sasanian occupation of Roman territory up to the Bosporus followed by a rapid campaign lead by Emperor Heraclius into the Sasanian rear devastating the empire’s heartland. While campaigning in the South Caucasus, the Emperor Heraclius concluded an alliance against the Sasanians with the Khazars, a Turkic tribe then subordinate to the Western Turkic Khaganate. With Sasanian defenses in disarray from Heraclius’s march, the Khazars smashed through the Caspian Gates and linked up with the Roman army outside of the important Sasanian fortress Tiflis. From there both Romans and Khazars went south across Armenia into northern Mesopotamia. Their advance into the Sasanian heartland and nearing the capital Ctesiphon compelled Persia to make peace, agreeing to return to the status quo belli. This war in the Caucasus in 625-627 was called the “world war of the 7th century” by the Russian historian Lev Gumilev, and similar to how the First World War weakened most participates, this war fatally weakened the Sasanians resulting in them losing control over the entire Caucasus to the Khazars.

In the decades following the war the Muslim Arabs entered into history, and with a series of campaigns in the 630’s the Arabs shattered Byzantine power south of the Taurus Mountains and simultaneously conquered the entirety of Sasanian Empire. Sometime shortly after the Roman-Sasanian War in the 620’s, the Khazars formed their own empire independent from the Turkic Khaganate with its heartland in the steppe lands between the Sulak River in modern Dagestan and the Atil River, now called the Volga. They subordinated the entire western steppe lands under their rule, including many northern forest tribes. As the Sasanians lost control of their Caucasus frontier, Khazars repeatedly invaded the south Caucasus in a series of raids which plunged the region into chaos. During this unsettled time, armies of Caliph Uthman reached Darband in 655. They campaigned north of the wall but it seems this was merely a raid or reconnaissance and the Caliphate only annexed Caucasian Albania in 701 under Muhammad ibn Marwan. In 705 Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik, who later commanded the failed siege of Constantinople, captured Derbent by sneaking through a secret passage with 100 men and opening the Caspian Gates. Maslama repaired the Derbent walls, and the Caliphate effectively replaced Sasanian Persia as the guardian of the Caspian Gates, protecting the civilized world from the northern nomadic hordes.

The Arabs came call the Caucasus their “greatest frontier”, the “mountains of tongues” referring to the numerous native languages to the region. Some Arabs came to believe the mythical Mount Qaf, a cosmic mountain were the mortal and supernatural realms met, was located in the northern Caucasus while others thought Caucasian Albania was home to the Garden of Eden. Over time the nomadic threat in the north and regional myths were mixed with Islam. The Arabs believed Allah had inspired Sasanian Persia to build the wall in order to protect the world from nomadic onslaught. “Had God not inspired the Kings of Persia to build Darband and its walls, as well as the other castles in the eastern Caucasus, there is no doubt that the kings of the Khazars, Alans, Avars, Turks and other nations would certainly have reached the areas of Baghdad and beyond”. To the Arabs, Derbent was “Bab al-Abwab”, “Gate of Gates”, signifying it as the most important passage.

The periods of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages were rife with a looming sense of apocalyptic doom among Christians. In the West the Roman Empire had collapsed, Eastern Imperial lands were destabilized from the war with Persia, Huns and Turks brought devastation to all the lands they reached, and finally the Arabs overturned nearly millennium of Greco-Roman and Persian rule in the Levant and Middle East. It was a series of successive cataclysms, and for the Christians of the era it must surely have felt like the end of the world was imminent. And for many suffering under nomadic invasion and state collapse it was indeed the end. During this period old Biblical legends captured the imagination of Christian minds, morphing into eschatological prophecies which declared the ends days to be soon coming. These prophecies were specifically about the tribes of Gog and Magog. First mentioned in Genesis as descendants of Japheth, they were later mentioned again in the Book of Ezekiel, specifically in Ezekiel 38. While in exile in Babylon, the Jewish prophet foretold that with the Jews being restored to Israel invaders from the north would attack, led by “Gog, of the land of Magog”.

This story was expanded upon by mostly Syrian Christians, who designated all of the northern barbarians beyond the Caucasus to be the tribes of Gog and Magog. These tribes were thought of as being the most barbarous or all, horribly ugly, eating insects and boiling aborted fetuses to create potions. The legend of Alexander the Great sealing the tribes of Gog and Magog off from the world was mixed with Christian apocalyptic prophecies. Christians came to believe that God would unleash the hordes of Gog and Magog against the world in a great and final war that would end with the Roman (Byzantine) Emperor renouncing his throne, surrendering his diadem at Golgotha, followed by the Second Coming of Christ and his establishment of the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. These legends were adopted by the Muslims, they called Alexander the Great “Dhu al-Qarnayn”, “The Two Horned One”, and called Gog and Magog “Yajuj and Majuj”. In Koran is it prophesized the coming of the end of the world will be marked by the tribes of Yajuj and Majuj breaking through the barrier that Alexander constructed.

Looking at this from a purely secular standpoint, it is obvious these eschatological prophecies were projected on to the very real apocalyptic menace that the steppe nomads posed. For a farmer in the path of a nomadic horde or a resident of a city targeted by them, it truly was the end times. It is also important to remember that across the entire medieval period the nomads were a perpetual menace. All of the greatest cities from that era were annihilated by nomads, Chang’an of the Tang Dynasty was sacked by the Uyghurs, Baghdad was destroyed by the Mongols, and Constantinople was captured by the Ottomans. Looking at it objectively, we can fairly say the prophecies of Gog and Magog did indeed come true repeatedly for nearly a thousand years.

Khazar – Arab wars

The highly expansionary Arabs reaching to Caucasus ignited a conflict with the equally formidable Khazar Khaganate. Due to the region’s geography their armies were funneled into the narrow passes of the Caucasus, with majority of fighting being for control of the Caspian Gates. For about 100 years from 655-737, the Arabs and Khazars were locked in unrestricted warfare. During this period the Arabs consolidated their rule over the South Caucasus, campaigning as fall as Lazica and Abasgia (modern day Georgian regions on the Black Sea). In the 670’s, 722, 726 and 730 in particular the Khazars penetrated into Azerbaijan devastating the region, with the Arabs crossing north as well in a series of back and forth. As mutual enemies of the Islamic Caliphate, Byzantium and the Khazars formed an alliance culminating in 733 with the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V marrying the daughter of the Khazar Khagan, with their half Byzantine, half Khazar son and successor later taking the throne as Emperor Leo IV “the Khazar”.

The most noteworthy event in the Arab-Khazar Wars occurred in 737 when Caliphate armies under command by Marwan “the Deaf” ibn Muhammad, later final Caliph of the Umayyads, launched a major invasion into the North Caucasus. With possibly as many as 150,000 men under his command, Marwan campaigned as far north as the Volga River, encircling the Khazar army and taking the Khagan captive. The Arabs forced the Khagan to convert to Islam before they returned south, but soon after the Khagan apostatized and the Arabs continued to raid north and attack Khazar allies. During these wars the Khazars were forced to move their capital further north from Semendar, likely either today’s Makhachkala or somewhere in its general vicinity, to Atil on the Volga which is thought to be close to modern Astrakhan. After 737 the Arab – Khazar Wars became less intense. The Caucasus mountains became the northern most limit of Islamic expansion as further conquests simply were not worth the costs. In hindsight, we can see that the Khazars played a similar role as the Franks in Europe, as they halted Islamic expansion from reaching further north. If the Khazars had failed in resisting the Arabs, it is possible world history would have developed radically different, namely the direction the future Russia would take.

In the decades following the war of 737 both the Caliphate and Khazars became less martial and more commercial. In 750 the Umayyads would be overthrown by the Abbasids, and in the centuries following the Caliphate would degenerate into a state ruled not by zealous warriors but eunuchs. Under Caliph Harun al-Rashid peace was made with the Khazars and future conflicts were much less severe, more in the form of raids than grand campaigns. During the Islamic period the Caliphate essentially copied Sasanian strategy in defending the Caspian Gates, with garrisons being supplied by agriculture grown by settlers relocated from Mesopotamia to the region south of Derbent. In later centuries when Islam was more codified and Muslims became more interested in proselytizing their religion, Derbent became a major center of missionary activity, from there Islam was spread across the Caucasus.

The Khazars, as they are famously known for, converted to Judaism. Their conversion is surrounded by myths, with the sources speaking more of legends than believable history, but it appears it occurred for two reasons. First, Judaism allowed the Khazars to remain independent as Christianity was subordinate to Byzantium and Islam to the Caliphate. Second, converting to Judaism opened up further trade opportunities. It appears the conversion was initiated by the al-Radhaniyya merchants, a Jewish community based out of Baghdad. The Radhanite merchants travelled north through the Caspian Gates to trade with the Khazars and in the process converted them to Judaism. Due to the geographical position of the Khazars they controlled all north-south trade in western Eurasia, and from land under their dominion they extracted tribute of furs, amber, slaves, and other goods which were exported south to the Islamic world. Similar to Russia with Siberia or British and French Empires in the New World, the fur trade was particularly lucrative, greatly enriching both merchants and the state.

Under Jewish influence the Khazars became less militaristic and more commercial, and their relations with the Caliphate improved with war decreasing while trade grew. Goods like furs would have either passed overland through the Caspian Gates or on merchant ships down the Volga, hugging the western coastline and stopping off at ports such as Derbent. Eventually the goods would be offloaded on Iran’s Caspian coast and caravans would transport them further across the Islamic world. The ships were likely from the Rus, or possibly the Vikings who came down from the Baltic across Russia’s river system. The Vikings themselves in 913 launched a major raid across the Caspian basin. With 500 ships and an agreement with Khazar Khagan, they tore through the entirety of the modern Azerbaijani and Iranian coasts. For the people living on the Caspian the attack was entirely unexpected, never before had they experienced foreign barbarians coming from the sea since it had always been peaceful. According to sources, the local inhabitants were in complete shock and Vikings left behind “rivers of blood” as they seized women and children, pillaging as far inland as modern Nagorno-Karabakh.

Mongols & Tamerlane

In later centuries the two great nomadic hosts to ride through the Caspian Gates took a different route than their predecessors. Both the Mongols and Tamerlane rode north through the gates after devastating Persia to attack the nomads living in the South Russian steppes. In pursuit of the former Shah of the Khwarezmian Empire, Jalal ad-Din, the Mongols entered the South Caucasus in 1221. They proceeded to raid Georgia before turning north through Derbent and the Caspian Gates. Penetrating into the North Caucasus steppes, the Mongols were met by an alliance of steppe nomads and lowland mountain tribes who the Mongols defeated. They went north and defeated the Rus at the Kalka River in 1223 before turning back to Chingiz Khan in the east. When the Mongols returned 14 years later they came directly from the east across the steppes, crossing the Volga before annihilating the Rus. A century and a half later, the great conqueror Tamerlane, from modern day Uzbekistan, rode north through the Caspian Gates while campaigning against the Golden Horde, the successor state of the Mongol Empire in the north-west Asia. After Derbent, the armies met at the Terek River in 1395 where Tamerlane defeated Khan Tokhtamysh which fatally crippled the Golden Horde, allowing the Russians to throw off the “Tartar Yoke”.

Peter the Great’s Conquest of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Gates first came under Russian dominion during Tsar Peter the Great’s war against Persia in the early 18th century. From 1722 to 1723 Russian armies and navy moved south through the gates, conquering the entire western and southern Caspian Sea coasts down to Resht in modern Iran. In pursuit of transforming Russian in a European Great Power, Peter the Great sought to open trade route between Russia and India, looking to secure the same commercial opportunities England was seizing in the subcontinent. An additional motivation was to free the Christian slaves that had been taken captive during nomadic raids and sold to slave traders who shipped southwards to markets in Persia. The Caspian Gates at this time were divided into several khanates all under up Safavid Persian vassalage, many of which were based on the slave trade of Russian Christians.

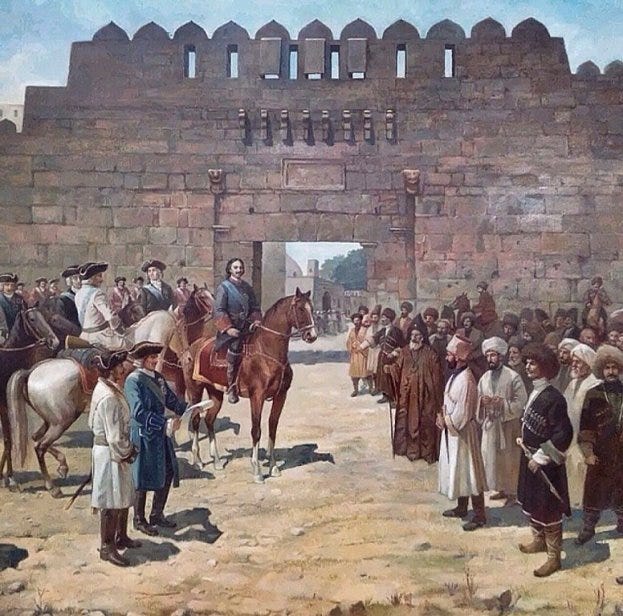

Very similar to the Viking raids in the 10th century, the Russians mostly came by sea with additional cavalry forces moving overland down the coast. From naval bases on the Volga the Russian Caspian Flotilla sailed south. First they landed at Tarki, capital of the Kumyk Shamkhalate, located on a hilltop overlooking the modern Makhachkala, where Peter the Great received the Shamkhal as a subject. The Russians then preceded south landing at Derbent, where Tsar Peter likewise received the Khan of Derbent who gave him the keys of the city, currently displayed in Saint Petersburg. Yet these conquests were not to last, by the 1730’s Nader Shah pushed Russia back over the Terek River in the North Caucasus. Only under the reign of Alexander I in the 1804-1813 did Derbent come under permanent Russian rule, of which it has remained under to this day. Additionally it is worth noting that Peter the Great not only established the Russian Baltic fleet, but also the Caspian Flotilla, along with the Black Sea fleet with his brief seizure of Azov, bringing Russian power to three seas.

The Caspian Gates in the World Wars

Despite the steppe nomads being long gone, the Caspian Gates have retained their enormous geopolitical importance into the modern industrialized world. This is entirely due to the oil reserves found around Baku on the Apsheron Peninsula in modern Azerbaijan during the late Russian Empire. This importance only grew with the discovery of major natural gas and oil reserves scattered across the Caspian Basin, as well as the development of these fields in former USSR Central Asian states, particularly in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. In the modern age it is not the Caspian Gates themselves that are so important, but rather control over this geopolitical region allows for influence over the entire Caspian basin and its energy reserves. Since their discovery there have been three significant attempts to pry these energy reserves out from Russia’s control.

The first attempt was during the interregnum between the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. As Russian armies disintegrated following the October Revolution in 1917, Ottoman forces were able to recover from their previous defeats and advance eastward with the aim of seizing Baku and its oil. The British, fearing Baku’s oil might fall into their enemy’s hands as well as having their own ambitions since the Royal Navy had converted from coal to oil just prior to the war, dispatched an expeditionary force from Mesopotamia through Iran to Baku in response. The British attempted to hold the city, but were forced to retreat east across the Caspian as they encountered a strong Ottoman force besieging the city and uncooperative Bolsheviks within. By September 1918 the Ottoman army under Enver Pasha had captured Baku, and then turned north in a mostly forgotten campaign which saw them go as far north as Port-Petrovsk, later renamed Makhachkala under the USSR. The Ottomans captured Port-Petrovsk, but were forced to retreat home as a week previous the Mundros Armistice was signed, ending the war. In the next few years the White Armies of South Russia were defeated and Soviet power was projected over the entirety of the former Tsarist Caucasian empire.

During the Second World War in 1942, the German High Command launched their infamous Plan Blau. This offensive is best known for culminating with the Battle of Stalingrad, it less known that Germany’s ultimate objective was not the city itself but instead the oil at Baku. Throughout the war, Germany was cut off from world trade and thus suffered from broad deficiencies in many natural resources including oil. Interestingly, the Third Reich was one of two countries who developed synthetic oil production, but real oil was still greatly required due to the heavy demands of mechanized warfare. At the time, approximately half of all Soviet oil production was located at Baku, therefore if the Wehrmacht had been successful in its objective it is fully possible Germany could have won the war. Instead, the Germany army made it as far as modern North Ossetia-Alania before being forced to retreat due the defeat at Stalingrad.

The Caspian Gates in the Contemporary NATO-Russian Confrontation

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of the three South Caucasus states, there has been a new geopolitical contest over control over the Caspian Sea’s energy reserves. In the past 30 years the Euro-Atlantic bloc has attempted to access directly the Caspian by building pipelines from the sea to Europe, bypassing Russia. The purpose of this was to lessen Europe’s reliance on Russian energy, thereby lessening Russia’s economic leverage over Europe. In the pursuit of this goal, the confrontation between the West and Russia has reignited as the Western Bloc attempted to promote pro-Western, anti-Russian regimes in the South Caucasus who would aid the West in pipeline construction. In turn Russia has recognized Western efforts in this sphere to be threatening and responded. This confrontation over the Caucasus and Caspian energy has also helped lay the groundwork for the current situation regarding Ukraine.

In 2003 the Rose Revolution in Georgia brought the Western backed Saakashvili regime to power. In 2006 both the South Caucasus natural gas pipeline and the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan oil pipeline were inaugurated, which directly connected Azerbaijan’s energy resources to Europe via Georgia and Turkey. Bringing Georgia into Western camp was crucial because, due to the Azerbaijan-Armenian conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and international sanctions on Iran, Georgia was the only viable transit country for Caspian energy to reach European markets. Additionally, there were attempts to build the Trans-Caspian pipeline which would have linked Turkmen and Kazakh energy to the preexisting pipeline infrastructure, but this project has been successfully vetoed by Russia.

The attempt by Western powers to extend their sphere of influence to Russia’s south and access energy reserves directly in the former USSR was viewed by Russia as a grave threat to its national security for two reasons. First, it was an attempt to break to their gas monopoly over Europe. Russia understood with its power greatly weakened by the fall of the USSR, its gas monopoly over Europe was one of its few assets and gave Russia leverage over Europe. Russia has maintained a policy to force all the former Soviet states to transit their energy through Russian territory before it reached its intended destination, as this would give Russia power over both the producer and downstream consumer. The Russian government believed that if Europe had sufficient energy supplies, it could freely disregard Russia’s opinion on crucial geopolitical matters without fear of a supply shock if Russia shut off gas supplies. Or in other words, Russia wanted to keep Europe dependent upon gas from Russia in order to force Europe to accept Russian geopolitical demands.

Secondly, Euro-Atlantic penetration into the South Caucasus was viewed as a ploy by America to encircle Russia from its south, additionally encircling Iran from the north, solidifying American global hegemony ensuring America’s ability to act unilaterally and unaccountably in the world. More specifically, in the Caucasus Russia has a number of major security concerns, namely separatism and terrorism in its Islamic republics of Ingushetia, Chechnya, and Dagestan. Russia feared the anti-Russian, pro-Western regime in Georgia would give aid to the anti-Russian militants operating within the territory of the Russian Federation. Moscow believes these militants and separatists threatened the entire disintegration of the Russian Federation if they were to be successful in their aims. Thus it was necessary that the regimes directly across Russia’s Caucasus border respected Russian security concerns and did not provide any assistance to the militants.

Despite initial Western successes, Russia progressively rolled back Western influence in the region. In 2008, in response to Georgian attempts to assert control over two pro-Russian breakaway regions, Russia launched a punitive war against Tbilisi which effectively ended prospects for Georgian accession to NATO and the EU. In 2012 the pro-American regime in Georgia was replaced by a regime friendlier to Moscow, controlled by an oligarch who made his wealth in Russia. The Trans-Caspian pipeline was blocked from being constructed. Russia’s success in this sphere is what allows it to act so boldly now during the current Ukrainian situation. As Russia retains a near monopoly over Europe’s gas supply, it is guaranteed that any serious European countermeasures to Russian actions against Kiev could see Europeans freeze this winter.

But what does Derbent and the historic Caspian Gate have to do with this? The significance of Derbent is that it has retained its crucial strategic importance as a north - south corridor from the Russian steppes to Azerbaijan, Iran, and the Middle East. Control over Caspian Gates provides Russia with a land corridor for its tanks to easily drive south through and ports for its Caspian Flotilla to sail from. Just as how hordes of Huns and Turks poured through Derbent, so could Russian armored forced today. In a distant echo to the past when the Vikings sailed down the Volga and raided the Caspian coast, the Russia Caspian Flotilla allows Russia to rapidly project force anywhere in the sea’s basin. Recently Russia’s Caspian Sea Flotilla has been modernized and relocated from Astrakhan to Makhachkala. During the Russian intervention in Syria, ships in the Caspian Sea Flotilla fired cruise missiles successfully hitting their targets in the Levant. This indicates that during a hypothetical conflict with the United States, Russia could likewise target American aircraft carriers in the Persian Gulf or eastern Mediterranean with missiles from their ships in the Caspian.

Following collapse of the USSR, and despite its temporary weakness, Russia never surrendered its right to use military force unilaterally to resolve crises in its favor. Control of Caspian Gates gives Russia the ability to easily project force across the Caspian Sea basin, and as a result all the states in the region have no choice but to respect Russian interests lest they share the same fate as Georgia in 2008, or what might befall Ukraine very soon. The fact that Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are so compliant with Russia is largely because they know Russia has retained military hegemony in that region, and should they attempt to resist, no one will come to save them.

If a severe crisis emerged anywhere in the Caspian Sea basin, control over the Caspian Gates and Derbent would allow Russia to intervene militarily. Possible scenarios could including, Azerbaijan being gripped by an internal destabilization similar to what Kazakhstan saw in early 2022, a need to directly intervene with force to save Russia’s treaty ally Armenia, or securing Turkmen energy reserves in the event of a destabilization there. Despite the enormous technological changes since the time of Sasanian Persia, the Khazars and Islamic Caliphate, Derbent and the Caspian Gates retain the same strategic importance.

I visited the city of Derbent several years ago. My interest in the place came from a YouTube video I watched during the height of the Russian intervention in the Syrian Civil War. The video was of an Islam scholar saying how Russia’s actions were a fulfillment of the prophecies of Gog and Magog and the coming of the end days. While I am not Muslim my curiosity piqued and I read more into this subject. I read about the same eschatology prophecies I have written about here, and years later when I visited Russia I knew I must visit Derbent.

Modern city is mostly Lezgin, a Dagestani ethnicity living in the republic’s south, and Azeri. As a westerner the city has a distinct oriental feel to it, “1001 nights” vibe, and much more Persian-esque atmosphere then Makhachkala which is only slightly to the north. If anyone has the chance to visit, I strongly recommend. It is a nice little city and the Naryn-Kala Fortress is a great sight. Additionally Makhachkala and especially Dagestan’s mountains are very fun places, I can’t recommend a better destination for a proper adventure.

I was taking calls and reading this article in between. Such a great piece of art! I have never logged into any site. Have done it for this now! Bravo for luring me into reading this one. regards

great writing!