Across the Southern Altai Mountains (1/2) - Grigory Spassky, 1809

Translation of a journey across the mountains of south Siberia - Russian settlements, Altai's ancient past, and the "rock-people"

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of an Grigory Ivanovich Spassky’s Путешествие по Южном Алтайским Горам (“A Journey Across the Altai Mountains”) which was originally published in the Сибирский Вестник (Siberian Vestnik) in 1818 & 1819. Admittedly, I had quite a bit of trouble locating the original text, as it seems the original text had not been fully digitized yet. At the very least, part one can be read here, on the electronic library of the Altai State University. This source of this translation can be found here, which is in modernized Russian. A translation of the second part of this text will be published in a follow up post.

Grigory Spassky was a Russian geologist and researcher of the Siberia, who explored the Altai Mountain region from 1808 to 1809. The text covers his travels in modern day eastern Kazakhstan, along the Irtysh River, and its tributary, the Bukhtarma River. During his journey he inspected several mines that were originally built by the enigmatic chuds, and encountered the curious “rock-people.”

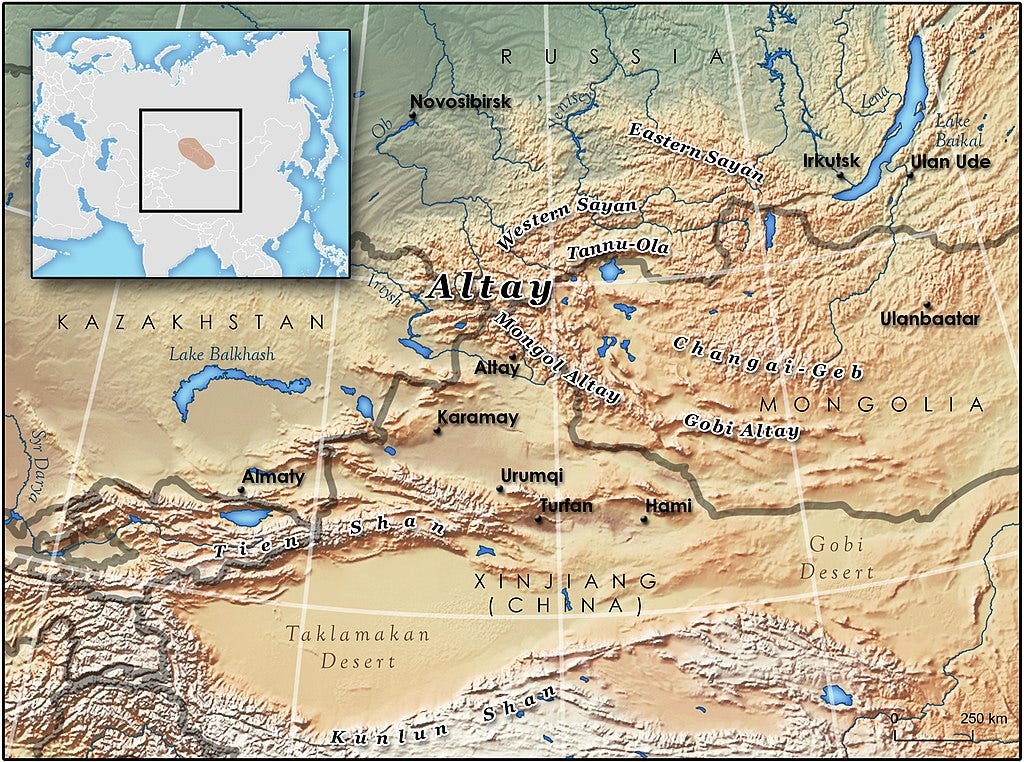

The Altai Mountains are one of the most remote and distant ranges in all of Eurasia, yet despite being being mostly unknown they are of great geographical and historical importance. The Altai Mountains stretch from the northwest to the southeast, from the west Siberian plain into the burning wastes of the Gobi Desert, and are often grouped together with the Sayan and Tannu-Ola Ranges, which encompass the Republic of Tuva. The majority of the Altai Mountains, including Tuva, reside inside of the Russia, but Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia also control parts of the mountains too. It is at the Altais where the borders of these four powers meet. Several of Siberia’s greatest rivers have their head waters in the broader Altai region a well, including the Ob, Irtysh and Yenisei, which are feed from the melting snows and glaciers on the mountains’ peaks. Additionally, the Altai region has enormous mineral deposits, which have been exploited since the Bronze Age.

A few notes on the Irtysh Line and the Bukhtarma fortress, both of which feature prominently in the text.

The Irtysh River in the early 19th century, prior to Russia’s conquest of the Kazakh steppes and Central Asia, was still very much a frontier region. Under Peter the Great in the early 18th century, Russia began constructing a series of fortresses along the Irtysh including Omsk, Pavlodar (first known as the Koryakovsky outpost), Semey (formerly Semipalatinsk), Ust-Kamenogorsk, and the Bukhtarma Fortress. Peter the Great had heard rumors of vast gold deposits at Yarkand in the Tarim Basin and hoped that the settlements along the Irtysh would serve as a base from where Cossacks and merchants could set out from to reach China, but with the aggressive Zungar Khanate in the way this did not come to pass.

These series of fortresses, collectively known as the Irtysh Line, served as important fortresses guarding southern Siberia during Russia’s conflict with the Zungar Khanate, a Mongolian state that was based in western Mongolia and northern Xinjiang before it was finally defeated by China’s Qing Dynasty in 1758. For more on the history Russia and the Zunagar Mongols, see Peter Perdue’s excellent book “China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia”.

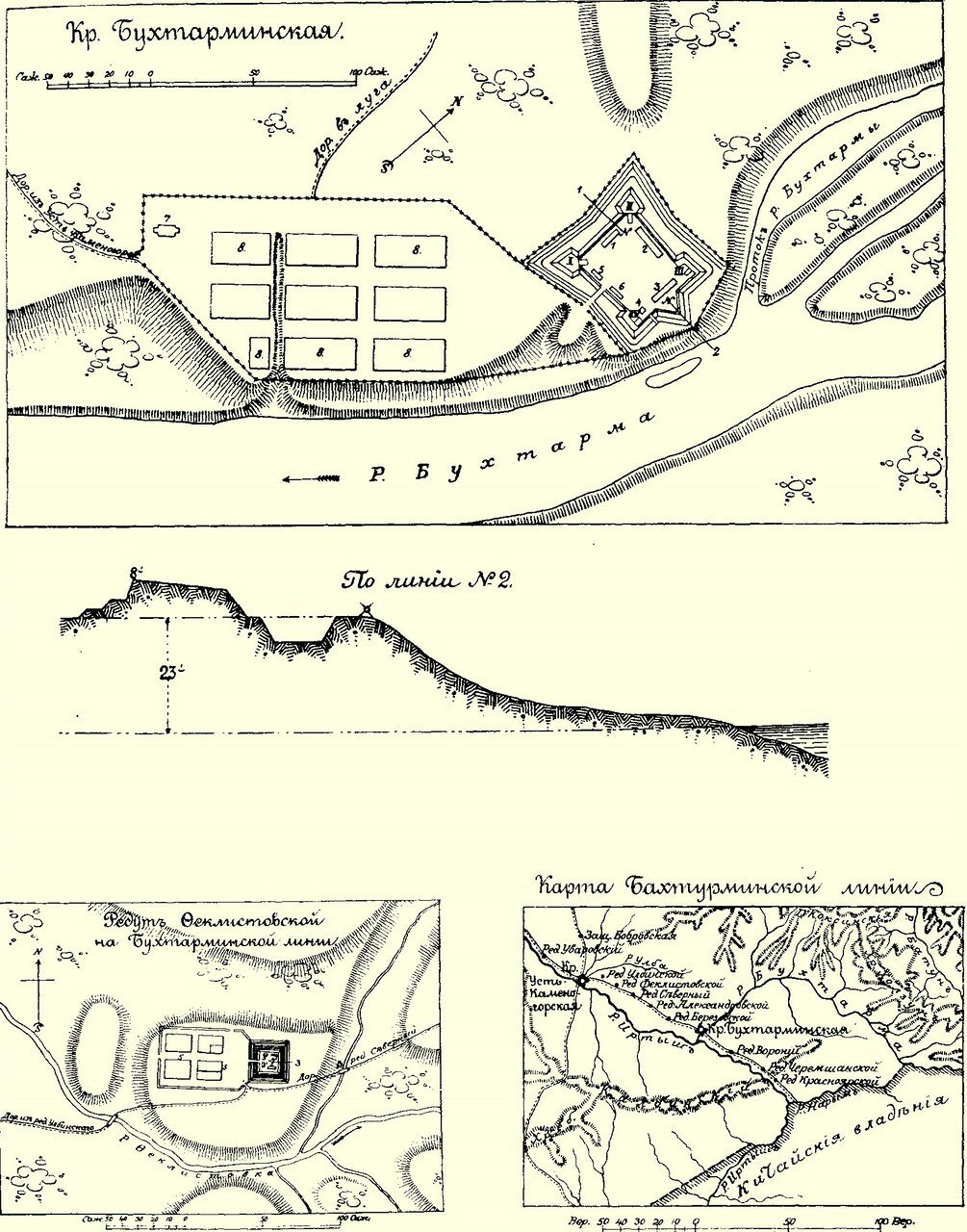

The Bukhtarma Fortress was first built as an outpost of the larger Ust-Kamenogorsk Fortress in 1761, at confluence of the River Bukhtarma with the River Irtysh. It was later expanded into being a fortress, and then later become a significant town in the region. Yet unfortunately, this fortress now lies deep underwater beneath the waves of the Bukhtarma Reservoir, created by the Bukhtarma Hydroelectric Power Plant in 1960, which was built only a few dozen kilometers from the site of the old fortress.

A few notes on the mining and metallurgy in the Altai Mountains. I would like to thank Twitter users @yiihya and @Irkutyanin1 for helping me with this translation. Yiihya in particular brought the real meaning of the word “чуд” (“chud”) to my attention, which refers to the pre-Russian, ancient inhabits of Siberia. Throughout the text, Spassky repeatedly refers to landmarks including petroglyphs and ancient mine shafts that were built by Siberia’s ancient peoples, known to Russians at the time as “chuds.” The chud mines that Spassky mentions are especially interesting. Little did Spassky or his fellow Russians know, these “chud” mines were likely built by the Scythians or Turks.

In the remote and distant history of Eurasia, two separate nomadic peoples have origins in the Altai Mountains, the Scythians and the Turks, and both fueled their imperial expansion by utilizing the vast metallurgical deposits found in the Altai Mountains. The Scythians are best known as the Indo-European Aryan nomads who lived on the Pontic Steppes of modern Ukraine and Russia during Greek antiquity, but their origins likely began around the Altai Mountains. In all likelyhood, the Scythians developed out the Andronovo Culture (2000–1150 BC), which encompasses much of Central Asia and southern Siberia. The oldest archaeological finding of Scythian artifacts was at the Arzhan Kurgans (1000-900 BC) in Tuva. It is believed the Scythians utilized the region’s copper to create weapons and armor that allowed them to expand westwards to the Pontic Steppes, the Near East, and possibly even the frontiers of China.

Centuries later, the ancient Turks nomadized in the Altai region, and were famed blacksmiths under the Rouran Khaganate, which existed in the 5th & 6th centuries, when China remained divided following the collapse of the Han Dynasty. In the mid-6th century, the Turks, led by Bumin Ashina, rose up against the Rouran and overthrew them and created an empire of their own, the Turk Khaganate. Afterwards, the Turks progressively spread out across Eurasia, ultimately reaching as far as Constantinople and Vienna, and culturally Turkicizing much of Eurasia in the process. The word “Turk” itself means “helmet”, a reference to their origins as blacksmiths and metal workers, and to the Otuken, the sacred mountain of the ancient Turks which was said to resemble a helmet.

The high concretion in the Altai region of mineral deposits and rivers, which functioned has trade arteries, primarily for furs which were one of the most valuable commodities in the pre-modern world, make the Altai Mountains one of the richest and most important regions in Eurasia. Considering that this region was the origin point of the Scythians and Turks, the Altai Mountains could rightly be called the epicenter of Eurasia. From here waves of nomads poured forth across the steppes and into to sedentary civilizations beyond, where they became the ruling elite of the new lands they conquered and created new civilizations in their wake. For more on the Scythians’ role in history, see Christopher Beckwith’s “The Scythian Empire.” The importance the Altai region has had on Eurasian history has mostly gone unrecognized thus far, and deserves further investigation.

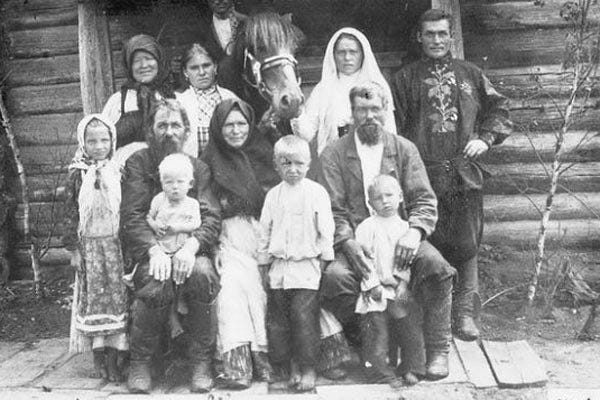

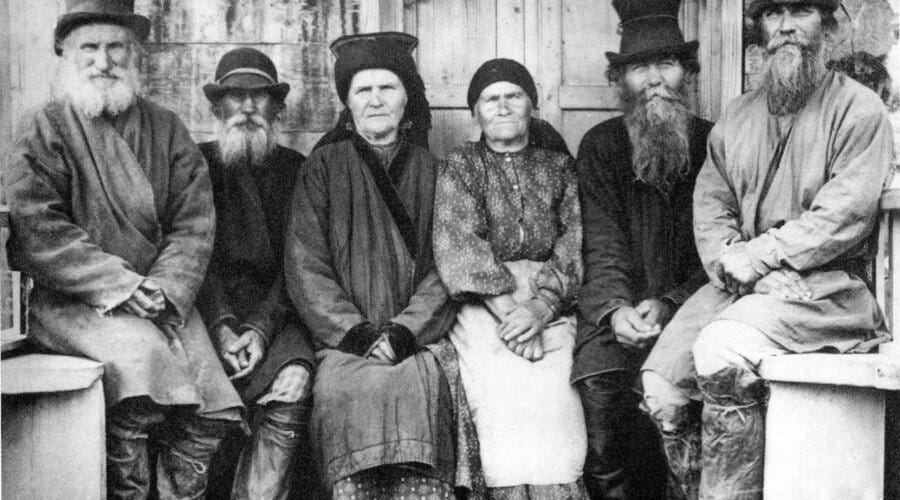

The other curiosity that Spassky mentions are the “rock-people” (Каменщики), who lived in the small villages tucked away in the mountains. These people are what are what were known as “Old Believers”, those who rejected the reforms made by the Russian Orthodox Church in the mid-17th century. The Old Believers faced immense persecution and thus fled to the most distant corners of Russia seeking refuge. Later under Catherine the Great at the end of the end of the 18th century, persecution against the Old Believers decreased. With greater tolerance from the Russian state and under increased pressure from Kazakhs to their south, the “rock people” issued a request to become imperial subjects, which was accepted in 1791. The rock people’s villages along the Bukhtarma and Uiman Rivers were incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Yet their status within the Russian Empire was most unusual. Instead of being considered peasants, they were classified as “inorodtsy”, meaning foreign aliens, a label usually reserved for ethnic non-Russians. This meant they had to pay the yasak tax (paid with furs) similar as Yakuts or Buryats, but were exempt from the taxes and labor obligations that existed for state-owned peasants, who constituted the majority of the Russian populations of the Altai Mountain region. As a result, the rock people enjoyed a more favorable position than typical peasants, despite being considered a racial aliens. As many state peasants in the Altai were forced to work in state mines and factories for their entire lives, many attempted to flee to the rock people and join them. Eventually this special status as abolished in the 1871 as a part of a general modernization effort aimed the empire’s administration.

For more on this subject, see “The ‘ethic of empire’ on the Siberian borderland: The peculiar case of the “rock people,” 1791–1878” by Andrei A. Znamenski, in “Peopling the Russian Periphery: Borderland Colonization in Eurasian History”, edited by Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Abby M. Schrader and Willard Sunderland.

Across the Southern Altai Mountains

Ust-Kamenogorsk Fortress, 22 May

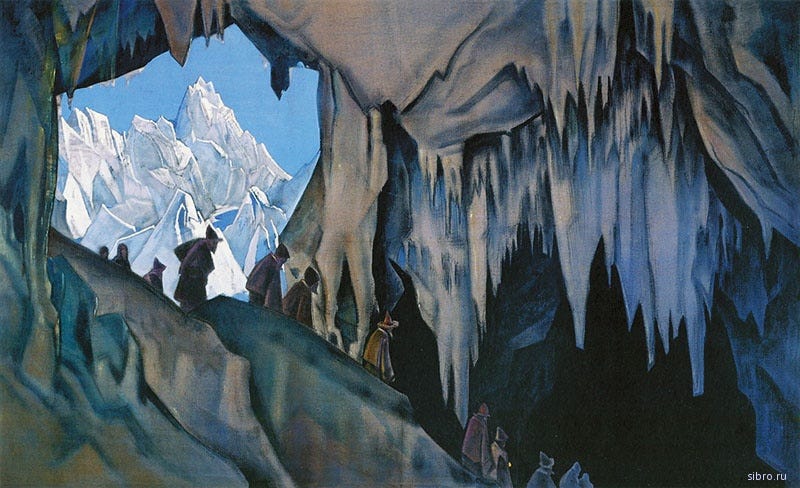

Without a doubt, the mountain heights are one of the most amazing spectacles in nature. Their peaks, either naked or covered with eternal snow, are enlightening for naturalists. Here, he learns of the great epochs this planet has inhabited and learns reverence before the powerful Creator.

Hitherto, the Alps have drawn the attention of observers. They have been described up to their smallest details, and many adorn their homes with their beloved art and publications created by travelers. But the Siberian mountains, for all the space they are scattered across, are yet so distant and difficult for travellers to reach and remain in almost primeval obscurity, most of all the Altai Mountains, famous for the rich mines opened at their bowels, and their beautiful location and the different natural creations all around them. All reported information on them consists of sketchy fragments from a few travelers and brief notes from miners. In such circumstances curiosity arises, I caress, that my description of my travels will not be deemed superfluous.

In the middle of May 1809 I headed out from Barnaul,1 lying on the River Ob. The time was early enough: water from the springs had not yet fallen into the river (in all of the Siberian mountain rivers, the waters rise twice annually: it first occurs in April and May, mostly in all northern regions; the second, which is said to be typical for Siberia, occurs in June and July. Both happen due to the melting snow on the mountains; but one occurs lower on the mountains and the other higher up. The average elevation of water in the River Ob, according to 22 years of observations made in Barnaul, is raised above ordinary summer levels during the first phase by 4 arshins2 and 11.75 vershoks,3 during the latter by 4 arshins and 6 vershoks.), the trees stood naked without leaves; the meadows and hills in place of greenery had instead a sad veil, a pitiful leftover (Siberian settlers, annually after the snow melts, usually have a bonfire of old and dry grass around the meadows, so that new growth is not hindered. This is what they call torch and burn.4 Sometimes a powerful wind will launch the fire and spread it across a very large area, burning the forest and even the villages. Travelers, trapped by such a fire, who do not have the ability to put it out, will light another fire before themselves and make sure the area in front of them is scorched, preventing the initial fire's further spread.5 They say, that from this it has become a custom among nomads to always have a flint with them. - Its pleasant to see, when in the quietness and darkness of night to see a fire rising up along the mountains. It is absolutely charming: here you alternate between seeing fiery kites, flaming buildings, fabulously illuminated fortresses and many other wonders - and you can see everything in the air.) As midday neared, the sad and deserted steppe changes: as we approach the area around the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress, it already holds all the charms of summer.

From here begins my journey along the southern Altai Mountains. Here the mountains adjoin with the plains, and the formidable Irtysh, freed they say from a rocky cleft, with the river digging its way out from its source and flowing into the Nor-Zaisan,6 and majestically its waters spread out widely across the steppe, and without its benefits land would be like the scorching deserts of Africa and we would be dead. - Thus the Irtysh transfers water from the limits of the high Altai Mountains to the feet of the Ural Mountains, across 1800 versts,7 as the Irtysh joins with great Ob.

The Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress is located on the right bank of the Irtysh, representing the frontier boundary line between Siberia and the Kyrgyz-Kazakh steppes. It was built in 1720 by Major-General Likharev, and receives its name either from the stony mountains that terminate nearby or from the Irtysh, which appears as if it is coming through a gate here. The fortress is surrounded by a single wall, equipped with a sufficient garrison, has one beautiful wooden church and a few good wooden houses, both for public and private uses. Up the Irtysh is located a small settlement, a little further are huts and Tashkentsty8 living in felt yurts, who have a decent trade, and herd horses, camels and cattle. A pier is located near the Tashkentsty yurts, where ores and minerals are unloaded, delivered by the Irtysh River from the Bukhtarma region, and destined for Kolyvano-Voskresensky factory.9

Although the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress lies on a flat area, its height (The figures for heights of places that I have given are in large part determined by Mr. Pansner, made by his barometric observations in 1806.) above sea level is 667 French feet.10

Bukhtarminskaya Fortress, 26 May

Departing from the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress, we soon entered a pleasant plain extending between the Irtysh and the Ulba River, which led us to high mountains and the narrow gorges, with which we had to go through to on our way to the Bukhtarminskaya fortress. The journey across these places was extremely slow: on the first we barely reached the Ulbinsky outpost that was 27 versts from the fortress. On this route every creek caused us to stop as if it was a major river: all the water coming off the mountains’ peaks in spring had destroyed all bridges and caused potholes in the road. At the Ulbinsky outpost I found lodgings for the night and affectionate hosts.

The following day we had already set off on horseback: first we rode a short distance to even ground, then went down to the River Prokhodnaya.11 It flows with a great noise along the narrow gorge between tall shale12 mountains. There was no bridge across this river, and we had to wade through it. After 16 versts we passed by the Feklistovsky outpost. The land around it would be good for farming. The Cossacks here are experienced in this, and therefore they will be well supplied.

At the northern redoubt13 after 20 versts, we prepared food for our horses, and on the same day we traveled another 8 versts to the Aleksandrovsky redoubt. Some of the places were wonderful. From the heights we enjoyed the spectacle of the far distant spires of the Ulba Mountains to the left. Two kinds of honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica et coerulea), a pea plant and other flowering bushes decorated the slopes of the mountains. Near the Ulba I could see paeony (Paeonia novam speciem) with white flowers. There are very rare here, but paeony (Paeonia officinalis) with crimson flowers is common everywhere.

After 17 versts from Aleksandrovsky redoubt there is the Berezovsky redoubt. - We arrived here very early the following day and continued on our journey to the Bukhtarminsky fortress, another 23 versts from here. Before we reached the lovely square where the fortress has been built upon, we had to get through the final valley between the mountains that are intersected by several rivers and filled by large boulders and gravel that have fallen off from nearby mountains. Exiting from here, I was amazed by the spectacle, unexpected as it was astonishing.

Here I saw a pleasant and wide valley, which from sides was enclosed by tall, round mountains, decorated with pine and fir trees. This valley, despite its roughness, seemed very smooth. It is 840 French feet above sea level. A solitary granite mountain, we named Shaggy Hill due to its round wooded peak. A few other mountains and hills covered with greenery, seemingly only located here, make this place that much rarer and more prefect. - All these elevations are in large part consisting of granite, black slate and lime stone.

Two famous rivers water this valley - the Irtysh and the Bukhtarma. They differ in their size, speed of the current, and their water: the Irtysh is deep, quiet and muddy; the Bukhtarma is small, quick and transparent. This difference can be seen not only when observing each river in its course, but also when they are joined. - The waters from both rivers flow separately for a significant distance after their confluence; eventually their waters get mixed together and difference between them can no longer be noticed.

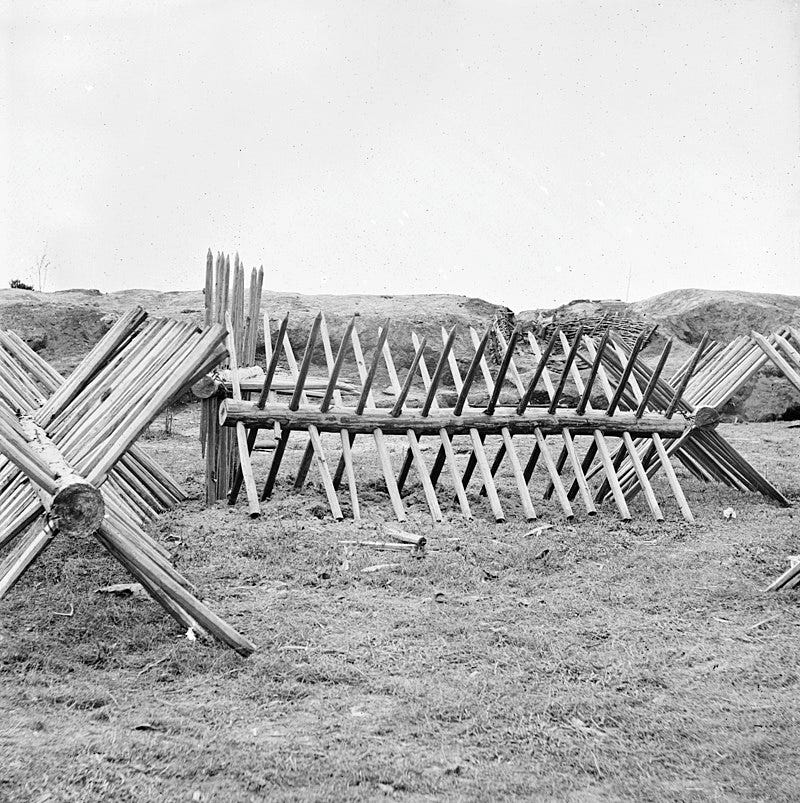

The Bukhtarminskaya fortress lies on the high right bank of the river, from which it receives its name, near to where the Bukhtarma joins the Irtysh. The shore rises above the surface of the water by 8 sazhens,14 and opposite bank is much lower. The opposite embankment is granite, not stretched out like a wild boar as usual, but horizontal slabs similar as shale: such a layering of granite is most often encountered here and in the Kolyvansky Mountains15 and was the reason for the naming of the fortress from the very beginning as Plitnyazhnaya.16 This fortress is surrounded by a rampart and shallow ditch, which is surrounded from above by Cheval de frise.17 On the western side there is a gate built from brick. Buildings inside that are wooden are: the house of the commandant, the barracks, the guardhouse; while the buildings made from stone are: the stores and storage cellar for gunpowder. Outside the fortress, buildings all generally wooden, such as: the church in the name of Saint Great-Martyr Catherine, infirmary, salt and food stores, customs and private homes.

This fortress is at the highest spot on the River Irtysh. It deserves attention not only for its picturesque location, but also because it is near one of the navigable rivers of Siberia, in the center, as they say, of many trading routes leading to cities in Russia, China and other Asian states. This represents great potential benefits to Russian commerce, which does not have a Kyakhta18 or any other similar place along the Siberian frontier. For merchants from cities deep inside of Russian who currently trade at Kyakhta, trading along the Irtysh would not only be a more convenient, it would also reduce their trip to only 2500 versts, 1000 versts less than before. They would also avoid the dangerous crossing over Baikal,19 by using the lower water between Tobol20 and Kyakhta, which was nearly completely abandoned due its many insurmountable difficulties21 despite the high prices paid for overland transport of cargo between Kyakhta and Tyumen,22 which vary at from 10 to 15 rubles an pound.

Developing commerce in this place is no less important for those who have a need for Asian products, as the large number of traders would be destroyed along with Kyakhta's monopoly on Asian trade, and a decrease in the freight charge would lower the prices of goods. But no matter how many benefits this enterprise promises, success does not correspond to expectations however, and trade at the Bukhtarminskaya fortress is unfortunately still in a most unfavorable position. The force of habits and prejudices take over above any other respects.

A few kurgans,23 scattered around the Bukhtarminskaya fortress, testify that not one beautiful and beneficial place for the pastoral life was forgotten by the ancient inhabitants of southern Siberia.

Located on the shore of the Irtysh near the fortress ramparts is a memorable and curious thing for any traveller: it is two human footprints: one is 5 vershoks long, and the other is 2.5, and a few hooves, ordinarily sized, made on a granite rock, having a length of 4 arshins and a width of 3. Their accuracy and proportionality led some to read these as real foot prints, while the Kyrgyz,24 according to their assumption that the stone was still soft and without having any further knowledge, called them the prints of Adam and maintained some special respect for them. - Leaving aside the initial innocent thoughts and superstitions of the Kyrgyz, it cannot, however, be said that these prints were produced in modern times, because such forgery could not be hidden from the attention of the Kyrgyz, who have nomadized near this place for a long time, and would have been known to the Russians; but, probably, they belong to the number of those ancient monuments, which in many places their ancestors25 left to be discovered by their posterity. Maybe, in these things, apparently of little significance, entail important historical events or items, pertaining to the faith of these ancient inhabitants (here is a similar example of this. In Kokand's possession,26 near the city Usha,27 the road to the small mosque, built on a high mountain,28 they show pits made from wooden staffs, horseshoe tracks, surviving across a few hundred years afterwards, as the Muhammedan prophet Suleiman29 came and went here for prayer. Located in the same mosque are indentations, representing the forehead, hands with fingers, knees and legs: the position of the praying prophet. Apparently, this place exists because of these signs, and once a year people travel here from many countries for pilgrimage.).

The view is the Bukhtarminskaya fortress from the southern side. It depicts: the River Bukhtarma, a cliff of layered granite, Shaggy Hill and other items.

Zyryanovsky Mine, 31 May

From the Bukhtarminskaya fortress we went to the east, having the River Bukhtarma before my eyes, and on the right was the Irtysh and the left were the forested mountains. - Before this we hesitated before heading out along the inconvenient road ahead, as the pleasantness of the current location kept us there as a we stopped and went on foot a few times; we were all the more reluctant to part ways from this place, as one with one's homeland upon leaving from it for a long time - such an alluring nature!

After 12 versts the horizon of the charming Bukhtarminskaya fortress was hidden from our eyes and we saw before us a ridge of limestone mountains. Located in one of the rocky mountains, a verst and a half from the river Bukhtarma is a cave which is currently not so entertaining travelers, as a few years before us there were letters written inside of one, but they were subsequently exterminated by careless ignorance (see, "Notes of Siberian Antiquities", pages 16 and 17.). This cave is not merely a historical landmark, but as its size is larger than others it deserves attention. Although its walls are smooth, they cannot be the work of human hands however. The writing was located inside the cave and outside it, as some have said. Now they remain only barely legible signs from what they were initially.

By the evening we already reached the village of Talovka, established by Polish settlers. It lies in a pleasant meadow on the shore of the Bukhtarma, shaded by poplars and birch trees. In the morning we crossed over on a raft, pulled by two horses, across the Bukhtarma. Near the ferry on the shallow area on both sides of the shore of the river we saw many multitudes of butterflies. - Among the ordinary one, I caught a podaliria (Р. Podalirius), which often fly around here together with swallowtails (P. Machaon). Prior, I had not noticed the Podaliria anywhere in Siberia. Located near the ferry is the village Krestovka, to which the road first goes across a poplar and aspen forest, then through some meadows. At Krestovka we changed horses and continued on the road to the Zyryanovsky mine: then between mountain valleys, then across some elevated fields dotted with sown grain. The Bukhtarma deviates towards to the north: behind it are the high bleached white mountains limiting the horizon; in front were fields and pastures mixed together in a pleasant diversity with groves and hills, covered in fresh bright greenery; villages with pretty, clean homes and scattered around were their herds of domesticated animals, showing the abundance and contentment of the residents, which brought this picture to life. It seemed as if, that the inhabitants of this place were absolutely happy.

But summer does not always reign here; the clear sun does not always gild this charming valley and the mountain peaks reflect its rays in the transparent streams of the Bukhtarma, Turgusun and Khairkumina: summer here is short, autumn is rainy, winter drags on and brings with it deep snows and storms. - Siberian winds are awful for travelers: they are like the Semun steppes of Africa (the Semun in Africa are known to have hot wind. It is accompanied with a great sand tornadoes, which suffocate the travelers it overtakes.), where travellers who fall asleep, instead of being buried by sand, they are buried in a coffin of snow, and when they emerge from under the snow after a few days they can barely breathe. Although falling snow in mountainous places in Siberia is not accompanied by such disastrous desolations as in Switzerland, similar did happen in the following adventure, and can serve as a startling example of this.

In 1805, 24 April, five people, residents of the village Klyuchevsky, had gone hunting at the mouth of the river Turgusun - the weather was cloudy and snowing, but apart from that it was quiet. At noon, 10 versts from the village, the promyshlenniki30 rose to on to one of the heights of the mountains, from which two of them, one after another, as usual, on skis went down the mountain. Meanwhile, the others also wanted to follow them, but saw the snow covering the mountain was cracking, and thus concluded there was loose snow and there might be a an avalanche - so they stopped. This loose snow differs from what threatens travelers in Switzerland. These fall only in winter during a thaw when a small massive breaks off and rolls down the hem of the mountain, gradually increasing in size from the snow adhering to it until it reaches an incredible size by the time it reaches the base of the mountain in relation to the distance it fell from.

Indeed, their conclusion was reasonable, and was immediately followed by the fall of the loose snow and they were witness to two of their comrades, located at the bottom of the mountain, being buried by snow. Not losing any time, they headed back to the village to inform them about this misfortune, however for all their haste they could not reach the village before nightfall, despite the road being more convenient for them than before, as they were not the first to go along it on skis.

Upon being notified about this, on the same night and along the same way, they returned with 5 other people with shovels for excavating the snow. With them was the elderly father of one of the buried, and with him was his other 15 year old son; but because of the darkness of night they could not go down the mountain, and decided to go back in order to bring more people to help them. They met 10 others along the road, and only reached the spot by morning and managed to start work, only for these 10 people to fall victim to a new avalanche: never had it happened prior for another avalanche to fall so soon after a prior one in the exact same place. Of these people, 3 were buried never to recovered, while others freed themselves from under the snow, or were pulled out by their comrades, without any long term consequences. One of them, Artemy Selivaov, whose son was buried during the first avalanche, owned his deliverance from death thanks to his dog that was with him. The dog found him and dug his head up enough from deep under the snow. He had nearly suffocated from a lack of air, but the dog did not think or had the strength to dig up his hands, and thus Selivanov was unable to free himself fully. He remained in this position for enough time and was eventually taken hold of by his deliver, who was almost continuously licking his face; the heat from the dog's breathe was good for him, but the licking did not help. Fortunately, he was located near a rock which protected his left side from being struck and made his position a bit more tolerable; but on the right side his hand and leg was injured: the pain for him was very strong. Finally their comrades were dug up completely, as if only to hear of new misfortunes, as besides the 3 people still buried, Selivanov’s young son was also a victim of the falling avalanche. He was abandoned on top of the mountain and they believe, for the love of his brother, also came down the mountain in order to rescue him as he had a shovel with him, but before reaching the bottom he was caught in the avalanche and was crushed. And so, Selivanov in the course of a day lost sons that he still mourns, while he himself was nearly made a victim by his parental tenderness.

The narrative of this misfortunate adventure distracted me from the Zyryanovsky mine. We arrived there on 29 May. The mine is located 50 versts from the Bukhtarminskaya fortress, and was opened by the locksmith apprentice Zyryanov, who it is named after. This Zyryanov, who was here hunting in 1791, accidentally encountered the chud mines in this area, took a few mineralized stones and presented them to the mountain authorities. Because the tests showed that the rocks contained enough silver, copper and lead, further reconnaissance was made, and this mine subsequently became one of the richest in the Altai range. Almost all local mines are found around the chud mines, and thus, their opening is more by chance, than by expert work or art.

The Zyryanovsky mine is surrounded nearby by low shale mountains, on its southeastern and western sides are granite mountains of a significant height, and to the north rise the snow covered Kholzun Mountains.31 The Zyryanovsky mine is 1168 feet above sea level, and the Kholzun Mountains between the peaks of both the Khairkumins is 6473 feet above sea level. Near the common building, consisting of 40 ministerial homes, the Maslyanka Creek flows from the south, uniting with the small Berezovka River at the eastern side, and flowing into the Bukhtarma. As the mine deepens below the Maslyanka water table, water squeezes through the stone layers along the mine shafts, making work difficult. Initially they were content with pumping it out with hand pumps, then they had to run it through an aqueduct at the bottom of the mountain at a distance of 168.5 sazhens, and finally they set up a horse drawn vehicle to transport the water.

Village of Korobishenskaya, 5 July

While travelling from the Zyryanovsky mine I was forced to satisfy a few curiosities of mine, and more still a duty of service, as the commanding authorities had entrusted me to inspect some of the local mines in this area; taking up this task was completely my choice, and the success of my trip depended on its completion.

Departing from Zyryanovsky mines on 5 July, we traveled on horseback, keeping the left bank of the Bezerovka River to our side. Losing sight of the majestic Kholzun, we traded it for an encounter with a different set of high mountains, consisting of clay, and chert and porphyry, cut in many places by quartz veins of different lengths and thicknesses, and sometimes mineralized. These mountains and meadows, watered by the river Bezerovka, which is shaded by birch and willow trees, made a pleasant and varied sight. After 10 versts from the mine we again passed by the poorly populated village of Solovyev, where few Kyrgyz yurts are are also located. On the left side from this village the Snegirevsky copper mine is visible, which opened in 1792 by Untersteiger Snegirev on top of an extensive preexisting chud mine. Almost the entire mountain on which the mine is located was excavated by the ancient mountain miners,32 but one of the cuts made for the mining of ores was of an excellent length: it extends from the base of the mountain and runs to the very top, from the southern side to the northern, which is very rare to encounter in chud work.

Another mine is located 30 versts from Solovyev, named after its prospector Murzintsovsky. Its ores are silver and they are of good quality. - The mine is not from a shaft made by the chuds, but from mineralized quartz, found on the surface of the mountains. Surveying the work here kept me here until the following day, and I had to spend the night in a wooden hut. There I was witness to a battle between a snake and a swallow. The snake crawled into the swallow's nest, located underneath the hut's ceiling, probably hunting for eggs, and was driven away by the swallow with the greatest courage and cries, which awakened me at the same time as the snake fell next to my bed. It did not cause me any harm.

The next day we passed through similar places as the previous day; 30 versts from the mine we passed by the village Malonarymskaya, the first with a population of Yasashny33 peasants, or the kamenshchiki (“rock-people”).34 The village lies by the river, from which it receives its name, constitutes one of the peaks of river Naryn, which flows into the Irtysh at border between Russia and China. On its western side is located a chain of high mountains, on which there is quite a lot of snow.

After 12 versts from the village Malonarymskaya we rose to such a height, from where from one point of view we could see everything, and the beauty and significance of the south Siberia mountains can only be imagined: on the right side towered the spires of the Naryn and Kurchum, that extend from the great Tarbagatai Mountains35 and receive theirs names from sources of the Naryn and Kurchuma rivers; on the left side are the snowy Kholzun Mountains proudly standing before all surrounding mountains. These giants stand between the water sheds of the Irtysh and the Ob. The rivers that flow from the southern and western slopes of Kholzun, include: Uba, Ulba, Turgusun, Khairkumin and Bukhtarma, all fill the Irtysh, and on the northern and eastern sides receive the origins of the Kokusun, constituting the peaks of the Katun, Small Khairkumin, Bastygan and Uiman which all unite with the great Ob. The first of these rivers is quick and shallow, and later are deep and wide. They depend on the abundance of snow on the mountain spires, from which they flow from and from where they have received their names.

Kokusun and Bukhtarma flow nearly parallel: one to the east, the other to the west. The first, under the name Katun, unites with the Biya and becomes the Ob, while the later merges with the Irtysh. The Biya flows out of Lake Altyn-Nor, or the Teletsky,36 and the Irtysh comes from Lake Zaisan. The position of these lakes is similar to one another. They are located between some of the tallest mountains and constitute expansive bodies of water, which possibly owe their existence to an earthquake or some other kind of significant natural occurrence, halting the flow of water that now flows into them, until the water reached its preexisting height and flowed back into its riverbed. These rivers could be the Chu and Chulyshman flowing into the Teletsky Lake, and the upper Irtysh into Nor-Zaisan. A similar origin is assumed for the Aral Sea and Baikal: the first from the rivers Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya (these rivers currently flow into the Aral Sea. According to ancient geographers, they were called the Oxus and Jaxartes, and flowed into the Caspian Sea.37 Some believe that an earthquake raised the riverbed of these rivers, and turned their course in the other direction, creating the Aral Sea, which was unknown to the ancients,38 and the other is from the river Angara (many believe Baikal to be a great pit filled by the Angara. The main evidence for this is: 1) its varying depths, showing an unusual unevenness at its bottom; 2) during calm weather, certain areas of Lake Baikal offer views of mountains and hills, particularly near the openings of the Goloustina and Polovinnaya rivers, where even large trees can be seen.

What could be more amazing for the mind and the heart than these heights, erected by the force of time, - these monuments of the world we inhabit. Here our spirit instantly crosses over from one feeling to another; it leaves carnal bounds, having only nature as its guide. The rocky steep mountains; their peaks, crowned with hills and pyramids, their crests and monstrous boars; slopes and valleys, pure white snow and the image of the everlasting realm of winter in the midst of summer: all this leads us to some horror and bewilderment. Contrary to this, the loveliness of the valleys, covered in carpets of green, gilded by the sun which is then sealed away by moving, roaming shadows cast down by the clouds; streams, coiling about like ribbons, as lines on a geographic map, and hills, adorned with trees, and smooth and round, - they fill the spirit with such pleasure, of which will be sought in vain across all imitative works of art.

All of these things kept us on the hills from quite a long time. From there we went down into the gorge, which had accompanied us until Korobishenskaya. The road was laid on the hem of a steep and high mountain, along both sides of the river Korobikha. This river aspires to the greatest speed and noise, flowing between large debris fallen from the mountain's rocks. - In many places horses on the sloped roads can barely stay on their feet; at places it was necessary to bypass large boulders and trees or ferry across the streams that flow into the Korobikha, which although are small, they are steep-banked.

Half way through this gorge night overtook us. The darkness of night and our unfamiliarity with the route increased the difficulty and danger. How we rejoinced, when saw fire, appearing between the trees from Korobishenskaya; our happiness was all the greater and all past worries were forgotten, when we learn that our companions from before had already arrived here, and prepared nice rooms for us. - We were met here with hospitality and good nature, as natural to our forefathers. Need and luxury - expelled from the heart of our fatherland; abundance and simplicity in manners - gave us refuge here.

The village Korobishenskaya lies on the left bank of the Bukhtarma, at the mouth of the river Korobikha, 22 versts from Malonarymskaya. In it lives the Kamenshchiki (this name is borrowed from the stony mountains. Local residents of this region during the time of their rebellion and flight - before they were declared as yasashny. Details on this will be discussed further on.), in not more than 20 homes. The village is located along the bank of the river, at the feet of tall slate mountains that are overgrown with forests. The same mountains adjoin the left bank of the river Bukhtarma: these forested mountains with their naked cliffs high up on their peaks give this place a bit of a sad look.

Located in modern day Altai Krai, on Ob River and the central Siberian steppe, quite far north of the Altai Mountains themselves

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 arshin = 71.12 cm (28 in)

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 vershok = 4.445 cm (1.75 in)

“палами и опалкою”

This purpose of this might not be clear to readers. The goal is stop the fire from spreading by preemptively burning the foliage its path. Russian firefighters would to have a similar practice. Moscow use to be entirely made of wood, so firefighters would demolish a house that was in a fire’s path, in order to prevent the fire's spread

Nor-Zaisan, also known as Lake Zaisan. “Nor” is the Mongolian word for lake. The Irtysh River begins in southeast Altai Mountains, near the modern day border between China and Mongolia. From its source to Lake Zaisan, it is called the Kara Irtysh

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 verst = 1.0668 km (3,500 ft)

Merchants for Tashkent, a significant oasis in Central Asia. In 1809 (same year as Spassky’s journey), Tashkent was seized by the Kokand Khanate

Located in Barnaul, built in the mid-18th century by Akinfiy Nikitich Demidov

A French foot was equivalent to 1.067877 English feet or roughly 13 inches

“Prokhodnaya” literally means crossing over

I believe the correct English language term for this is schist. “сланцовых гор” could also be translated as shale or slate, which are two different types of rocks, but after some research on the geology of Altai Mountain, I believe schist is more accurate

Cossack redoubts were watch towers, often built inside of a fortress. Russian redoubts are different from classical European ones, which were outlying defensive structures from the main fortress, usually featuring earthworks, wooden palisades or other others features that provided cover to infantry and artillery

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.1336 m (7 ft)

A small mountain range that are a part of the northwestern Altai Mountains. Located north of Ust-Kamenogorsk inside of Altai Krai, Russia

Meaning “tiled”, likely a reference to how shale rock looks

Anti-cavalry defensive obstacles. See photo below as reference

A trading post that existed on the Russian-Chinese (now Mongolian) border. The only place where Russia could trade with China

Until the early 20th century, Lake Baikal could only be crossed by ship, as southern shoreline is extremely mountainous

A tributary of the Irtysh. The Tobol River flows into the Irtysh at the modern day city of Tobolsk. The Tobol is a significant river, a drainage basin that reaches Chelyabinsk near the Urals

Not known what is being referenced here

City in western Siberia

Large earthen burial mounds built by the ancient Aryan nomads of the Eurasian steppes

Actually Kazakhs. Russians at the time regularly referred to Kazakhs as Kyrgyz, and modern Kyrgyz as Wild-stone (Дикокаменный Кыргрз) or Kara-Kyrgyz

Not ancestors of the Kazakhs. It is unclear whether Spassky understands this

The Kokand Khanate, possessions meaning its empire

Osh, in the Fergana Valley, modern day Kyrgyzstan

The Sulaiman-Too Mountain, located in the middle of Osh

King Solomon. In the Quran he is a prophet

Cossacks and others, who hunted and exploited the natural resources in remote regions of the empire, similar the French coureurs de bois in North America

Smaller range that is a part of the Altai Mountains. West of Zyryanovsky mine, along the modern day Kazakh-Russian border

“горорытцами”, гора (mountain) + рыть (to dig). The word “горорытец” was made up compound word invented by the author

Yasak payers. See introduction for explanation

See introduction for explanation

Mountain range south of the Altai, that runs along the modern Kazakh-Chinese border

In the Altai Republic, Russia

Spassky is referring to the Uzboy River, a river that once existed which connected the Oxus.Amu-Darya to the Caspian. Several ancient Greco-Roman geogrpahers reference this river, including Strabo, Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy

Ancient geographers had very imprecise knowledge of distant regions; their ignorance of the Aral is not necessarily proof that it did not exist at the time. That said, they were aware of the Khiva Oasis located just south of the Aral Sea, which was known to the Greeks and Romans as Chorasmia

Excellent post, my favorite I've seen of your translations so far!