From Verny to Karakol - Petr A. Galitsky, 1874

Translation of a Traveler's Journey from Almaty to Lake Issyk Kul

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

От Верного до Каракола, or “From Verny to Karakol” is a short travelogue by Petr Galitsky, detailing his journey in 1874 across the Tianshan Mountains of Russian Tukestan. His journey took him from the city of Verny, across the Trans-Ili Alatau Range, to Karakol near Lake Issyk Kul. Verny had only been founded on 4th February 1854 as a Cossack fortress amidst the Kazakh Great Horde, while Karakol was even younger, founded only in 1869. At the time, there were no rail connections between Central Asia and the rest of Russia, making the Tianshan Mountains one of the most distant and remote corners of the Russian Empire. The region was sparsely settled by Russian colonists, with nomadic Kazakhs and Kyrgyz being the region’s main inhabitants. Only in the Soviet era would the treacherous paths over the mountains be replaced by paved roads. Unfortunately I could find nothing on who Galitsky was, or if his journey had any additional purpose. Nevertheless, his article is a nice read, and quite interesting as it gives an idea of what conditions were like in Russia’s Central Asian empire, on the frontiers of Chinese Turkestan.

Galitsky’s articles was originally published in Сборник “Сибирь” ( Journal “Siberia”), pages 294-304, published in Saint Petersburg in 1876 - the journal can be found online here.

I translated this from an online source written in modernized Russian - the source can be found here.

From Verny to Karakol (Travel Notes)

The road from Verny1 to the Uzun-Agach picket2 runs westwards, along the snowy peaks of the Ala-tau range, and from its many gorges, along stony riverbeds, come quick flowing streams and rivers that intersect the road. These streams serve as irrigation for fields, by means of ditches. Along the Almaty line3 there are many kurgans4 and views of large and small hills. These are probably graves or memorials of ancient inhabitants of the region, because modern graves of the native population are made from brick and come in very diverse forms, some with jagged walls and towers on their corners.

I camped at the third station, Kastek,5 so that early in the morning I could cross the Kactek gorge in the Ala-tau,6 and exit straight to the Karabulak Piket,7 and shorten my trip by more than 200 verts, in order to avoid the dangers of crossing over stormy Chu River near Tokmak, where the bridge has not yet been built. I was told, that the other day the oblast’s8 doctor had dangerously crossed over these rivers on a wagon, and the coachman behind him in another wagon was knocked over by the strong current of the water and was pulled out unconscious.

Even for those unfamiliar with hard riding in the high mountains, travelling 50 versts9 in the mountains and valley, along roads that rise and descend dozens of times along steep trails, is always better than putting your life at grave danger by crossing over the stormy river Chu.

On the 2nd of August I left early in the morning, spent 12 hours in the saddle and only 8 hours later in the evening, broken and wearied, I arrive to the Karabulak picket.

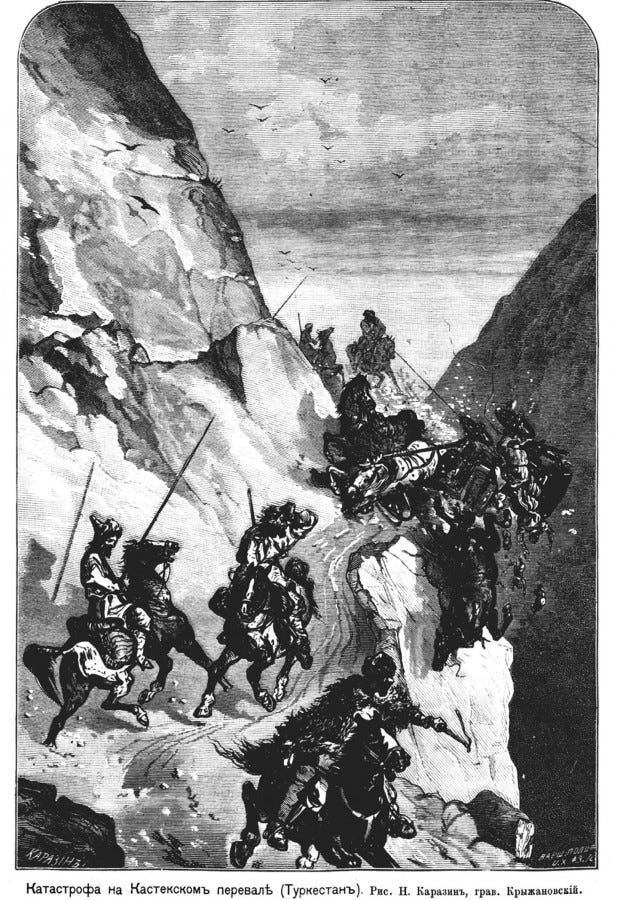

The Kastek gorge amazes travelers with its savagery and grandiose views; it consists of cliffs and rocks piled on top of each of other and between the gorge’s wall the traveler is forced to climb, zigzagging and spiraling up the gorge to the mountain top. The vegetation there is very poor, without any trees at all. The Kastek River can be heard making its way down the gorge.

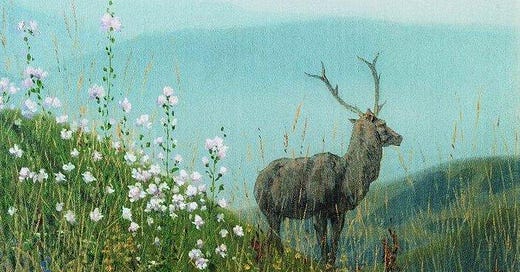

Along the cliffs are numerous mountainous grouse,10 which run around the rocks with amazing quickness and fly only in random bursts; one also encounters many wild pigeons. My guide told me, that here in spring one can also encounter many marmots and porcupines, but I did not have a change to see any.

The road between Karabulak and Jel-Aryk picket11 runs along rolling hills and is generally smooth and comfortable for riding in a wagon. Three versts before the picket, mountainous terrain begins again, which is said, is the doorway to the Boom Gorge,12 which rises to an elevated plateau, where Lake Issyk Kul is located. Not far away from the picket is a wonderful bridge13 that crosses over the Chu River, built in a particularly wild spot between two cliffs that protrude over the river, with the incessant roar of the River Chu below. The bridge is very pretty and quite durable (in length it is 12 sazhens,14 and about 6 sazhens above the surface of the water). I admired its well-engineered construction in such a remote place for a long time. Its construction probably cost a fair amount.

The road along the Boom Gorge to the Kok-Mainak picket15 was very dangerous. Immediately after Jel-Aryk we entered the Boom gorge, along which the turbulent Chu River roars, and up to 8pm in the evening it rose, and then fell. First we went along the left bank of the river, and then went over across the river to the right bank. With crossing the river, the route amounts to 24 versts, but it is really 50 versts because of the route’s steppe slopes that rise and descend back and forth. In the majority of cases horses cling to the edges of the mountain path, where there is already no possibility to change course or turn back. The path leads along a cornice16 with no rail to guard its edge, and meanwhile, a troika17 can only barely has enough room to go along the cliff’s edge. With the path going along a sheer cliff that hangs over the gorge, and the gorge’s bottom at a terrible depth below, the Chu River can barely be heard. Your spirit freezes as you look down, and with a feeling of self-preservation you will involuntarily jump from the wagon, not paying attention to the coachman’s belief that the horses can be trusted. The mountains here are of various colors, red, yellow, green, brown and black. The vegetation is very sparse, with almost no trees at all.

The coachman showed me a small bush, which has pistachios that can be collected, but to reach it over the rocky cliffs is quite difficult. In some places near the road, large deposits of red and white clay are visible, it is as if nature has built an elongate building that looks like a barracks: only window and doors need to be built.

Before we had exited from the gorge, the darkness of night overtook us, and therefore we travelled the remainder of the journey quietly, but safely. Tired and broken from riding along the rocky road, with great pleasure I drank some tea before lying down to sleep, so that we could set off early the next morning and continue travelling in such a mountainous land. The next picket is Kute-Mulda.18

The road continues as before along the gorge’s steep slopes and descents; it is a cornice but they are not so high or dangerous. The Chu River here is not as turbulent as before and resembles an ordinary small river. From afar on the high mountains we could see a line of carts pulled by oxen climbing up the path along a cornice, and we had to wait for them to descend, which took more than an hour. If two groups suddenly meet on a cornice’s edge, one must return back to where they can disperse and make way for the other group. Here I encountered a new kind of thorny plant with yellow berries, called “kurek” in Kyrgyz; another kind of this plant, teresken,19 is also thorny, which grows across the land and serves as the favorite abode of pheasants.

After 16 versts we exited from the gorge and found ourselves on an elevated plateau located 5300 feet20 above sea level that spreads out to encompass the Lake Issyk Kul (which means the “Warm Lake”). Having passed through so many dangerous places along the road in the mountains and knowing that the route to Karakol goes along completely flat terrain, I already considered myself completely happy as an unexpected delay that cost me a few hours of time could otherwise had ended with serious consequences.

At the Kut-Muldyn picket, they harnessed my horses to a troika made in Tyumen.21 The mailman expressed his desire to travel with me for 4 versts, to the first good fishing spot at Lake Issyk Kul. There I inspected the large nets that had caught carp and marinka,22 I wanted to eat them in a soup but none of the fish were fresh, and therefore I immediately departed on my way. After 8 versts a rabbit jumped underneath the legs of my horse, which frightened the horse, causing her to stumble to the side. The other horse followed her and the whole troika veered to the side at full speed and ran into a field of grassy knolls.23 The coachman and Cossack were thrown off the wagon, while I was tossed around like a ball, but somehow I avoided any injuries as the horses suddenly stopped, rooted to the spot. I jumped out of the wagon – to do what, I don’t know. The front wheels were shattered into pieces, only one wheel remained fully intact and this is what had made the horses halt. We had to wait 2 hours for the troika to be repaired, and in the meantime we went hunting for pheasants, which are found around the lake’s shores in great quantities. I came across 2 litters of pheasants, but they were young and still small, and there were no handsome males with them.

The road to Karakol runs mostly along Lake Issyk Kul, approaching and then moving away from the lake; with the mountain ranges Ala-tau and Alexanderovsky24 gradually approaching. They border the lake to its north and south, giving it a picturesque view.

It was perfectly quiet and sunny day; I spent a long time admiring the vast expanse of dark blue water, which would appear white near the shore at times. Many places along the lake’s shore were covered in shrubby charganak and sea buckthorn;25 three years ago here there were many boars and tigers, but with the post road and establishment of towns in the region, these animals retreated into the mountains. I was told by one of the mailmen, who settled here in 1869, that boars use to besiege the picket when it was still under construction, and he would be forced sit inside all day due to the blockade. Hunting for these animals was very profitable, but dangerous. And he had once killed a boar that weighed 15 pounds.

Currently along the shore of the lake, except for the pickets and Cossack stations for changing horses, for the next 200 miles only 2 large villages exist, Saznovskoe and Peobrazhenskoe;26 in the first the construction of a stone church has already been completed, but there is not yet a priest, and in the other village there is already more than 100 houses. Buildings here are mostly made from brick and the roof is made of wooden planks, making these villages a beautiful sight. The peasants were resettled here from different provinces in Russian and Siberia, and they appeared quite satisfied with their new location and they are primarily engaged in farming. The soil is untouched and is irrigated through ditches, the farmers are richly rewarded for their work.

Some of the peasants and postmasters fish in the lake, using various kinds of nets, but this work does not result in much as they have only recently started, or because they are not very good at it, or there is simply not enough demand for fish here. Of course, Verny and nearby stations with a population more than 20,000 could serve as a market for these fish if it could be delivered there while still fresh, but the Ala-tau Mountains and its snowy peaks, its steppe gorges and abysses, all serve as insurmountable obstacles to this being realized. I was told that from Issyk Kul to Verny, as a straight journey, is about 80 versts and involves crossing a few mountain passes, which can be crossed on horseback and reach the city in a day and a half, but the route is full of danger and is closed for parts of the year, and in winter its almost entirely impassable.

I heard that there is another mountain pass that can be crossed on foot; in the past local Kyrgyz often travelled along it to cross the Ala-tau for baranta.27 Along this route, dzhigit28 (youths) early in the morning with bridle and whip would travel to go fish; - climbing over cliffs and jumping over mountain creeks with great danger to their lives, all to reach the other side of the mountains by nightfall, where they would find the best horse they could and then herd off anymore horses they could find, herding them to a less treacherous gorge, where they could easily cross back over the mountains with they prey.

I did not have a chance to see any water birds on the lake, - except only a few loons, geese and ducks; maybe it depends on the time of the year; during the winter the lake does not freeze, demonstrating its name (the warm lake), - they say on the water’s surface there are many geese, swans and ducks of different breeds. The different birds I encountered: black storks, herons, sandpipers, curlews, quail, lapwings, flocks of great bustards and countless mountain partridges, or, as here they are called, grouse.29 The diversity of avian predators here is great; I encountered: bald eagle, whitetail, bearded vulture, hawks of different sizes and breeds, and a very beautiful, as large as a dove, with a white in lock of hair on its head,30 like a falcon. Around the road in the bushes there are countless rabbits. Here, they are generally smaller than Siberian rabbits, their coat is colored brown, which in the winter does not change, their tail is about 2 vershoks31 in length, with a black stripe at its tip.

Near the village of Sazanovsky, the lake begins to narrow and the mountains approach. The village Preobrazhenskoe is located in the so-called Tyup, in the final bay of the lake. The peasants make use of firewood and timber from the forests on the mountain gorges; forest are predominately spruce; from the gorges they also get different berries; raspberries, black current; mushrooms can also be found in abundance there, and sea buckthorn are also commonly found, which can be collected in the thousands, but they say the berries do not taste good, nor are they good for making alcohol as it will taste like tree sap.

The famous Issyk Kul root grows in the gorges here and is commonly known for its toxicity. I did not see this plant, but I was told they resemble the leaves of a wild carrot and has as similarly oblong root, but it is white in color. The plant seems to be toxic, as animals never approach places where it grows, and by simply smelling it a person will get a headache. They say, one Cossack who wanted to bring the plant’s root home, dug it up and placed it inside his hat between the linen and quickly a strong headache began, and it only relented once he threw it away. Cases of poisoning from this root are very common among people in Verny.

From Preobrazhenskoe, the road turns to the right, towards the Alexandrovsky Mountains that shelters the small Karakol River with its foothills, and the river only becomes visible at the town of Karakol, established in 1869. House are mostly made from brick; the streets are straight and well planned out; at the square a stone church is being built that can hold around 200 people (church services are held at a temporary church, made of blocks and felt).

At the village’s square there are many small shops, in which Sarts32 mostly sell different Asian products; there is one Russian shop, which sells all necessities; there is also a warehouse, and a Rensky Cellar.33 On the corner of the square there is a bank being built, made from stone. Not only will government money be kept there , guarded behind iron bars and iron shutters over the windows, but officials must sit and behind these iron bars and shutters as well. The storeroom and inner treasury room are only connected to the outer rooms through a separate iron door.

The population of Karakol is in largely military; hosting the 1st Turkestan Line battalion, stationed at full force including a garrison and a mountain battery. The personnel of this unit help animate life in such a distant and remote corner of our vast fatherland. Despite Karakol’s recent establishment as a town, it already has very lovely homes, and town has been wonderfully developed. Already a house for the battalion commander has been built, and for the county judge, the battery commander, and more. Gardens with flower beds are being planted, a summer club building is being set up, a public garden is being set up, and a large sum has already been allocated for the construction of a school made of stone. With such quick success there is hope that in 100 years’ time Karakol will have become a pretty country town; and with its wonderful and healthy climate, its bountiful land, it can attract a large number of residents.

During summers the heat is not very strong, and winters are very short and mild. Freezing temperatures reaches no more than -10 degrees; it is almost impossible to ride on a sleigh. Initially there was a lack of garden vegetables here; but with correct care and experience, different kinds of vegetables can be grown and harvested here in abundance; only watermelons fail to ripen and grow large, unlike those in Verny. Fruits are also not in any short supply, but they are not produced locally; apples and grapes are transported from Kuldzha,34 which from here is not very far. Bread is not expensive: flour, wheat, and rye are sold at around 25 kopeks35 for a quarter of a pound; a quarter pound of oats is 1 ruble,36 firewood is 2 rubles a sazhen, candles are 6 rubles a pound. Only apartments and imported goods are expensive, - first is because the city is not yet fully built, and the second is because of a lack of demand.

Fifteen versts from Karakol, on the road to Muzart,37 is the excellent Aksu Hot Mineral Waters. The road passes by the small village of Aksu38 and the wooden bridge over the Aksu River, turning right and clinging to the edge of the river’s right bank, and leading to the mineral waters, located in a wild and picturesque place. The left bank of the river is almost a sheer cliff, densely covered by fir trees; the right bank is more gently sloped and dotted with huge granite boulders. Some of these rocks have rolled down and blocked the flow of water, which makes the mountain stream furiously howl.

The first hot spring follows from the base of a giant granite rock. Apricot trees hang overhead. Its water is crystal clear, there is no sulfuric smell, and its temperature reaches 30 degrees. The depth of the spring’s pool is more than one arshin.39 I did not put more than a leg into the water because it seemed too hot, but later when I put my whole body in, it felt fine, the heat was gentle, from which I did not want to part from. Bathing in the Arasan mineral waters near the city of Qapal in Semireche oblast, you can perceive the smell of sulfur, which causes the body to relax despite its otherwise unpleasant scent; I have not noticed this here, and it seems to me, one can sit in the pool for more than an hour without an unpleasant sensations arising, except for the pleasant warmness of the water. On the other side of the river there are two more springs with similarly hot waters; one shoots out from an overhanging granite rock and resembles hot rain, and bathers either sit or lie down underneath it. I did have a chance to experience the pleasures of this second spring, because there was no bridge across the river; the only other crossing was via a tree that had fallen over the stream. This was very dangerous, those who had to cross over had to go on their knees, holding on to the branches of the tree and knowing that even the smallest mistake would result in them being swept away in the stormy river current that was furiously smashing into the fallen boulders. They say, at the upper reaches of the Aksu River, there is a spring, in which the water is even hotter. The Aksu mineral waters, in the opinion of doctor Zh., contain large amounts of iron and alkalinity, and can be very beneficial for those suffering from rheumatism and skin diseases. On the branches of the trees that hang over the spring, flags and clothing of different colors are tied; these are probably signs of appreciation from locals who have been cured. With the increase of people in this corner of our empire and with development of accommodations for patients, as at Arasan, the Aksu mineral water can attract a significant amount of guests. Some of the residents of Karakol already use these springs and receive relief from them.

Another wonderful thing about Karakol – is that Lake Issyk Kul is located only 12 versts from the city. I will try to describe it, partly from stories from local residents, partly from my personal observations. The lake Issyk Kul spreads out between two snowy mountain ranges; it is about 200 versts in length, and in width it is about 80 versts. Its water is saline, but at its shores where numerous mountain creeks flow into the lake, the saline level is lower than in the lake’s middle; these creeks are numbered around 80. In the lake is found an abundance of fish; carp can reach up to 25 pounds in weight. The fish are very tasty and oily. Russians catch them in nets, while Kyrgyz do not have a similar tool and instead catch fish when they enter the mouth of the rivers to go up stream and lay eggs. Local Kyrgyz have a story from their distant past, that where there is now the lake, there were once 2 cities, which were destroyed due to an earthquake and were flooded with water, which has been shown to be true by many different things found sunken under the lake’s surface.

In all of its picturesque beauty, the lake feels deserted, because only rarely will you encounter a lonely goose floating along its surface, or a flock of geese flying away in a line; while on the water sailing for 12 hours we did not encounter one living creature. After a verst away from the shoreline, the water becomes salty in taste, so in extreme cases it can be used in preparing food. The water’s transparency was not what they said it was. Things can be clearly seen at a depth of more than a sazhen. Using this opportunity, we examined the depth of the lake and it became clear that its bottom was formerly inhabited. During this time we sailed a distance of half a verst from the shore, and divers pulled out for us pottery shards, square and oblong bricks, and a worn-out millstone, human skulls and a finely made jug with a broken handle and base. I was told that people have even found copper and bronze items in the lake; I myself saw a peasant in the Oytal station40 with bronze jug that weighed 4 and a half pounds, shaped in the form of a overturned deep plate with a hole in the middle on 3 legs, quite well made, found during the past autumn and I heard from him that on occasion he can see entire human skeletons at the bottom of the lake. Rowers who sailed here last year said they saw the remains of buildings below. Generally, one must agree with the tradition of the natives and assume that the lake’s territory was once inhabited long ago, and due to some kind of unexpected upheaval the land was flooded by water. The lake’s depth is difficult to determine accurately, in some places we dropped a lead line to a depth of 300 sazhens and still could not reach the bottom. The shoreline of the lake is mostly sand, and in some places stony, so that for 200 sazhens from the shore we had trouble sailing through underwater rocks. The southern shore of the lake is dotted with nomadic Kyrgyz, and along the northern shore are Russian settlements and a laid out postal road. In general, the lake hides its archeological potential and plentiful fish with its size and depth, - it deserves detailed and scholarly research. The authorities seemingly have already take care of this, making arrangements to construct a ship costing more than 1000 rubles, but the construction of this ship was entrusted to a person who lacked understanding of how to do it; the ship went nowhere as it was unfit for sailing, and currently it rests in its side, without any use.

The road from Verny to Karakol, while full of danger, is not as bad as one would expect for the region that has only recently been settled. The pickets are all made of bricks, with roofs made from clay and chopped straw, and are bleached; the houses consist of 2 buildings divided by a canopy; in 1 room is the kitchen and for the coachman, and the other is divided into 2 rooms, 1 for the postman and the other for travellers, the rooms are kept tidy; some walls are covered with wallpaper; in evenings stearin candles are used. Most postmen have already acquired a farm, so that travellers can get milk, chicken, ducks, etc, for an inexpensive price. At one of the pickets I was treated to fresh trout, fried with eggs, and it was very tasty. I asked how they caught it, and they answered, that Kyrgyz hit them in sticks while they are swimming up mountain creeks; and while travelling to the next station, I saw a few completely naked Kyrgyz with a stick in the river, presumably, attempting to catch trout.

10 September 1874

Postscript

For more on Russia’s empire in Central Asia, see my book thread on Alexander Morrison’s “The Russian Conquest of Central Asia: A Study in Imperial Expansion” - the thread is still progress.

The name for Almaty during the Russian Empire

Uzun-Agach is today a small town, just west of Verny/modern Almaty. At the time of Petr’s journey, it was merely an outpost of Verny meant to defend against nomadic raiding

A line of forts and outposts in the Almaty River Valley that Russia used to control the region of Semireche. The line was centered on Verny

Large earth mounds that steppe nomads created as burial and memorial sites

“Stations” are cossack settlements. Kastek is located 80km west of Almaty

The Trans-Ili Alatau. These mountains divide the Almaty region and Lake Issyk Kul, and run westwards along the modern Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan border, dividing Semireche from the Chu River Valley

A picket was a small outpost. The Karabulak picket was located in the lower Kastek gorge

Oblast is the Russian equivalent for province

A verst is an old Russian unit of measurement, equivalent to 1 kilometer

A type of bird

On the Chu River in Kyrgyzstan, about half way between Issyk Kul and Bishkek

Along the Chu River towards Issyk Kul

Likely modern day Krasny Most

An old Russian unit of measurement. One sazhen equals 2.13 meters, or 7 feet

Modern day Kok Moynok Eki, near the western end of Issyk Kul

A mountain cliff that hangs over the abyss

A wagon pulled by three horses. The Russian word for three is “три” or “tri”, hence “troika”

Unknown location, likely around Issyk Kul

A small thorny bush. Also called Krascheninnikovia in Russian

Russian feet are the same as American feet. 5300 ft = 1615.44 meters

City in Western Siberia

A type of fish also known as Schizothorax

Original text says “по кочковатому чию”

Now called the Terskey Ala-too range, south of Issyk Kul

Known in Russian as Облепиха, or as Hippophae in Latin. Its berries make for excellent tea

Along the northern side of the lake

Baranta is a Turkic word for the concept of punitive raiding. As higher authority over nomadic tribes was either weak or non-existent, people would have to take justice into their own hands

Turkic word for trick riding, but colloquially used to describe young warriors and raiders

“и бесчисленное множество горных куропаток, или, как здесь их называют, рябчиков.”

Described as a “хохлол,” as in the hairstyle of the Zaporzohian Cossacks

Old Russian unit of measurement, 1 vershok is 4.445cm, or 1.75 inches

Sarts refer to Central Asia’s sedentary population, farmers and traders

Alcohol store common throughout the Russian Empire

Known in English as Ghulja, or as Yining in Chinese. Located in the Ili Valley in Xinjiang, China, just east of Verny/Almaty

Russian word for currency. Equivalent to an American cent

Russian currency. Equivalent to an American dollar

Mountain pass over the Tianshan Mountains, from the Tekes River to Aksu in the Tarim Basin. All of these places are within China

At modern day Teploklyuchenka, east of Karakol

Old unit of measurement, 71cm/2.5ft

On the northern shore of the lake