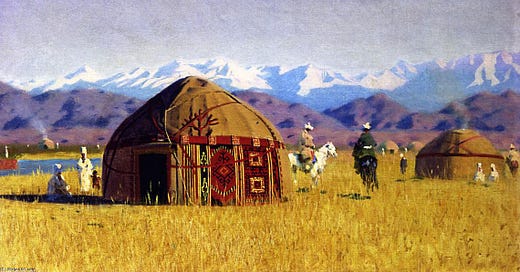

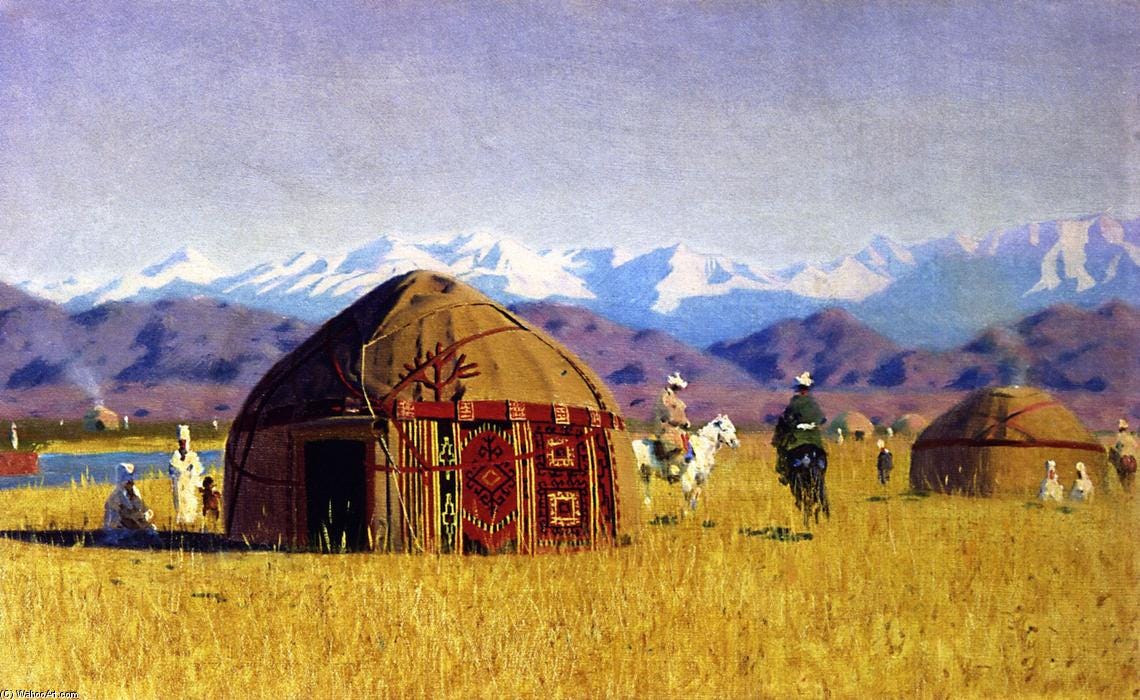

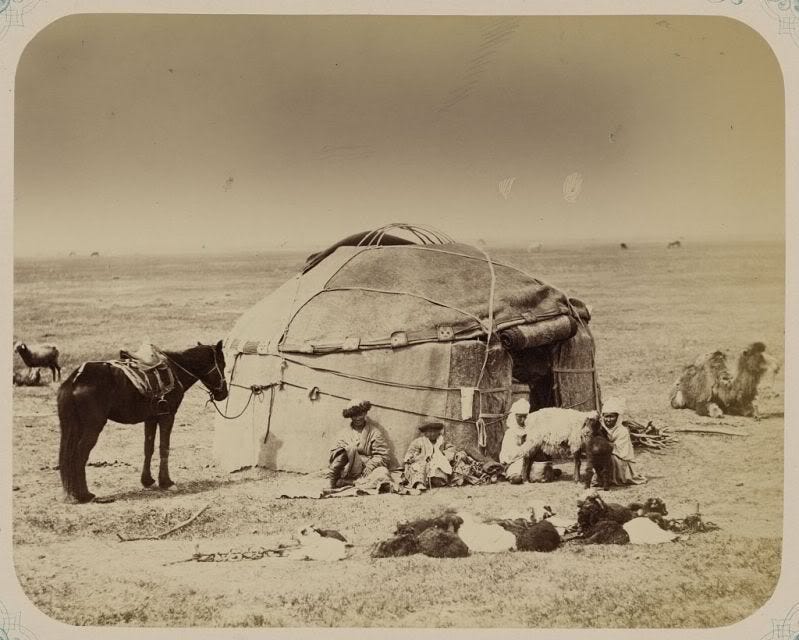

On the Road to Kashgar. In a Kyrgyz Aul - Chokan Valikhanov, 1860

Translation of a Kazakh spy's travels among the Kyrgyz of the Wild-stone Horde

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

The translation below is a collection of excepts from Chokan Valikhanov’s “Essays on Zungaria” (“Очерки Джунгарии”). Valikhanov made this journey in 1858-1859, and wrote this text in Saint Petersburg in 1860. It was first published in “Notes of the Russian Geographical Society” (1861, book I, pp. 184-200, book II, pp. 35-58). This is one of Valikhanov’s most important works where he not only writes about his espionage mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan on behalf of the Russian Empire, but also records fascinating ethnographic information concerning local Central Asian peoples. Valikhanov’s writings would become a sensation among the Russian Empire’s educated society, as he provided insights into the people and geography of the empire’s newly acquired Central Asian holdings that only someone who could speak the local language and fit in with the local cultural milieu could provide.

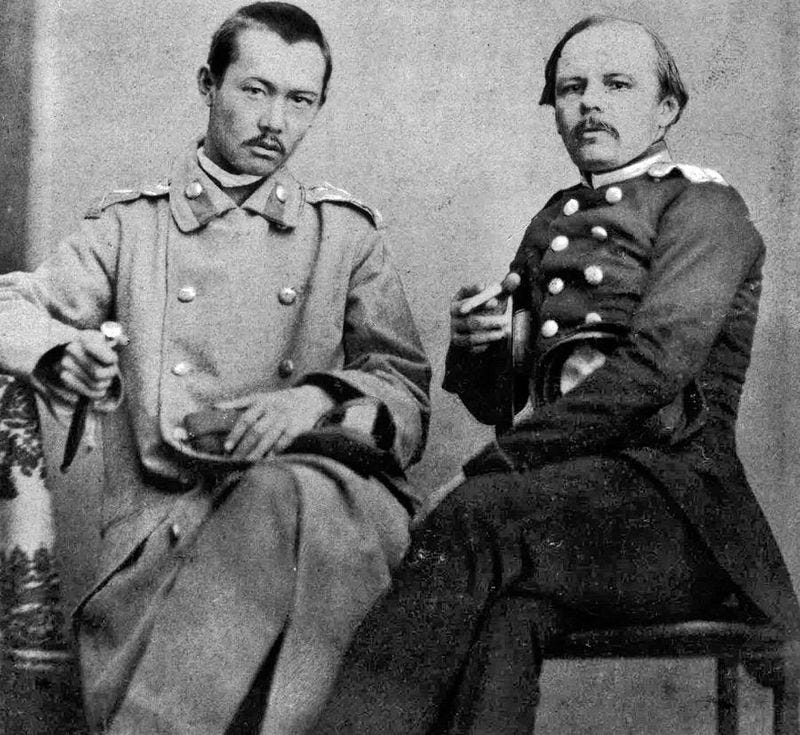

Chokan Chingisovich Valikhanov was born in 1835 in modern day northern Kazakhstan, and was a descendant of both Chingis Khan and Ablai Khan, the founder of the Kazakh Middle Horde. In 1847 Valikhanov enrolled in a Russian Imperial cadet school in Omsk, where he learned Russian and befriend Fedor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky had been exiled to Omsk in 1850 due his involvement with Petrashevsky Circle, a revolutionary political organization. In the 1850’s Russia was only beginning to penetrate south into the Kazakh steppes and conquer large tracts of Central Asia. The region nevertheless remained largely a mystery to the Russians, and in order to better understand the territories they had recently conquered, Valikhanov was sent on a series of secret missions to explore the region. In 1861 Valikhanov became ill with tuberculosis, and eventually died from the disease in 1865, at age 29. He has remained a very important figure in both Russia and Kazakhstan, as he not only wrote fascinating “Great Game” literature, but also represents Russia and Kazakhstan’s “prisoyedineniye” (присоединение), Russia and Kazakhstan’s “coming together” as it is often called.

Since the time of Peter the Great in the early 18th century, Russia had maintained an interest in establishing trade connections to the oases cities of Kashgar and Yarkand in the western end of the Tarim Basin. Russia’s access had been prevented due to the lawless Kazakhs and the hostile Mongolian Zungar Khanate on the steppes, and later the Qing Dynasty’s strict control over the border. As Russia seized control over Semireche (modern day southeastern Kazakhstan) in the 1850’s, their interests in the Tarim Basin were reactivated. Valikhanov’s mission was largely for purposes of reconnaissance. He scouted out the route to Kashgar, and recorded all the necessary information concerning the local towns, populations, etc. Unfortunately, Chokan Valikhanov has remained in relative obscurity in the English-speaking world. His travels are not only important chapters to the “Great Game”, Russia and Britain’s imperial expansion into Inner Asia, but his life demonstrates how Russia functions as an imperial power. Very similar to the Romans, Russia has always had a remarkable ability to befriend, co-opt, include, and make of use of local elite in their imperial projects. The typical Anglo-American understanding of Russia as being a purely repressive state is comically wrong, and this view only exists due to it being promulgated in the media for political reasons.

A few additional things should be noted to provide context for the reader.

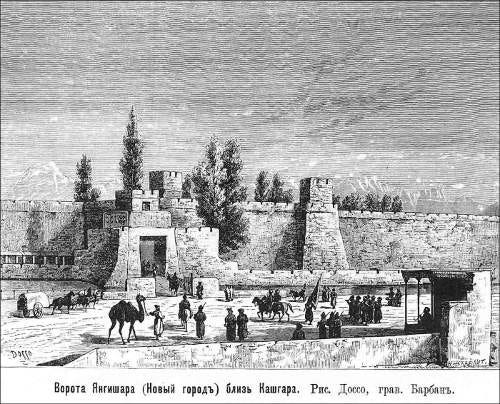

Valikhanov notes Kashgar had recently undergone an uprising, which was dealt with harshly by the Qing authorities. Kashgar and the Tarim Basin was conquered by the Qing Dynasty in the mid-18th century. The Qing had exiled a segment of the local landowning elite, who were known as Khojas. Many Khojas fled west to the Pamir Mountains and the Kokand Khanate in the Fergana Valley. For the next century, these Khojas periodically invaded and stirred uprisings in Kashgar and the Tarim Basin, sometimes with Kokandi assistance. This all culminated in the 1860’s and 1870’s, when Yakub Beg, an adventurer from Kokand, took advantage of a local Islamic rebellion that was raging across western China and carved out an Emirate for himself in the Tarim Basin. For more on the Kokand Khanate and it relations with the Qing Dynasty, I would recommend “The Rise and Fall of the Kokand Khanate” by Scott C. Levi.

Valikhanov also notes the influence of Tatar Mullahs in promulgating Islam among the steppe nomads. Despite being nominally Muslim, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz prior to their incorporation into the Russian Empire were anything but pious, Sharia abiding Muslims. Instead, their traditional and tribal Shamanistic religion had largely persisted. This was changed by the Russian imperial state, beginning under the reign of Catherine the Great. The Russian state believed the general lawlessness, the constant raiding and counter-raiding, was all a result of the steppe nomads lacking a firm religious and moral code. In order to pacify the steppes the Russians encouraged Tatar Mullahs from the Volga region to proselytize among the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, and to firmly bring them into accordance with Islamic Sharia. This was also meant to physically tie them to a local mosque, instead of their regular movements and migrations across the steppe which were viewed as being inherently destabilizing. Thus it can be said that Russia effectively converted the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz to Islam. For more on this, I recommend “For Prophet and Tsar” by Robert Crews.

The source of the translation can be found here.

Lastly, a collection of Valikhanov’s writings have recently been translated into English, the volume in PDF format can be found here.

On the Road to Kashgar. In a Kyrgyz Aul

At the end of 1858 I successfully joined a Kokandi1 caravan, disguised as a Kokandi merchant, in order to penetrate into Kashgar. Since the famous Marco Polo (1272) and the Jesuit Goes2 (1603), only 2 other Europeans have visited the city of Kashgar: a German, last name unknown, who was an officer in the service of the East Indian Company and kept travel notes of his extremely curious journey which have been preserved, and an educated Prussian named Adolf Schlagintveit.3 The first, while in Kashgar, was beaten with bamboo sticks so badly that for two days he could not sit on a horse, the second was beheaded and his head was placed on top of a tower made of other human heads.

Kashgar belongs to the Chinese province of Nan-Lu4 (southern line) and has been famous since the time of Ptolemy5 as a major caravan city, especially for its extensive tea trade. Kashgar for Asia has the same meaning Kyakhta6 has for us or as Shanghai and Canton has for Europeans.7 Additionally, the city of Kashgar is famous in the East for its charming “Chaukans” (Uyghur world for unmarried women), which are young girls that any visitor to the city can marry during their stay.8 Kashgar is also famous for its musicians, dancers, and for having the best hashish in the world. Thanks to this glory, Kashgar serves as a destination to where all of Asia’s merchants flock to. Here one can see Tibetans with Persians, Indians with Volga Tatars, Afghans, Armenians, Jews, Gypsies (multani and lulu)9 and some of our countrymen, runaway Siberian Cossacks.

Recently, this city began to acquire fame for something else. A tower made of human heads has appeared, they have begun to slaughter people as casually they would slaughter chickens.

As goes a local folk song, “it is difficult to keep a horse in Kashgar city, because a bundle of hay costs 12 puls, but its even harder to keep your head, because vai! vai!” This strange ending to the song expresses the frightened state in which the locals are to be found in. Recently there have been several bloody uprising in Kashgar in favor of the Khojas,10 descendants of the former rulers of Kashgar.11 The rioters did not slaughter that many Chinese, but instead their local clients in Kashgar, one of which for example, who served as an official under the Chinese authorities, and another who yawned, and a third who is a black mountaineer.12 After exiling Kashgar’s Khojas, which they have managed to do despite their military weakness, the Chinese first began to loot the city, then they used their state herds to trample the local wheat fields, seized local women, damaged the local mosque and tombs, and began ceremonial executions which were performed with terrible slowness.

When we arrived to Kashgar, the Chinese had only recently finished torturing the locals. Entering through the gate, we could see the city’s entrance was decorated with a line of thin poles, on which were hanging cages containing the yellowed skulls of executed locals. The city had begun to calm down. The new local ruler, installed by the Chinese, rode around wearing a Mandarin hat and would hit anyone who did not out of his way fast enough. Relations with Kokand were restored, the Kokand envoy had already lived in Kashgar for more than a month, and every day caravans from Bukhara13 and Kokand filled up the caravan-sarai.14 The arrival of our caravan to the city caused great excitement. Even before our arrival the Kyrgyz had spread a rumor that a caravan of 500 camels was coming from Russia (we have only 60), loaded with chests in which firearms are hidden; and the caravan’s commander had the name “Iron Board” ( a name the Kyrgyz invented, probably, because the caravanbashi15 had an iron bed board), and that he is a suspicious person and thus must be Russian. There are no absurdities that an Asian would not believe, the more absurd the rumor is the more probable it appears. The Chinese, as is known, are not any different from other Asians in these terms, - and that is what happened. Fortunately, the Kokand envoy personally knew our caravanbashi and some of our other traders; thus it was only with the intercession of the Kokandis were allowed into the city. For now I will not discuss the Chinese and local authorities’ interrogations of our caravan, as time does not allow for it nor is it the right place, as I only intend to talk about my travels and my time with the wild-stone horde.16 (…)

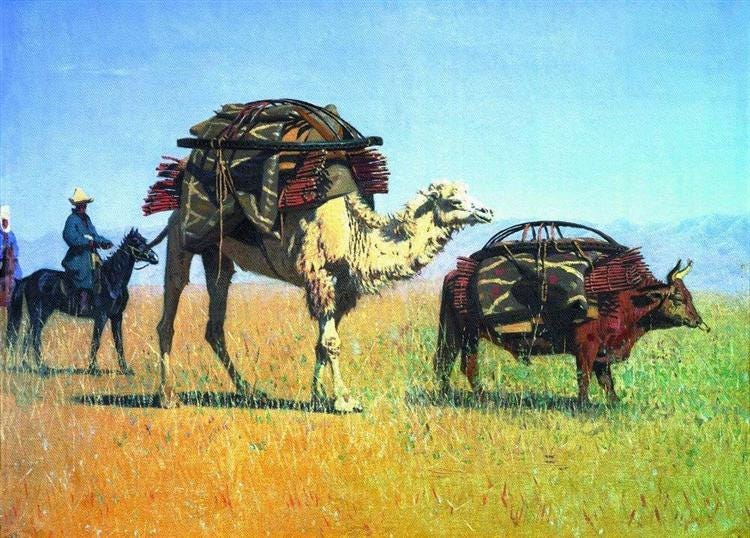

My journey began on 28th May 1858. I joined with a trade caravan, which was camped at Karamul, about 30 versts17 from the town of Kopal,18 the caravan had departed from the city of Semipalatinsk19 and was run by merchants from Kokand and Bukhara. Travelling with the caravan were 8 mobile yurts; 100 camels, 65 horses, 34 servants and merchandise worth 20,000 rubles20 in value. I was known among the caravan peoples by the name of Alimbay and thought to be a relative of the caravanbashi, the Venerable Musabay.

On the 29th of May the caravan headed out. The weather was favorable for our journey as we went along the picket road to the Altyn-Emel picket, along the wonderful valleys of the Alatau foothills. The fields were full of orange tulips, eastern poppies and yellow birds flew across the long stems of white mallow (Emberiza bruniceps). After marching 25 versts in the cool evening air, the caravan set up camp somewhere along a bank of a raging river under the shadows of tall poplars or a silverleafed dzhigda; people were having fun and talking around the brightly lit campfire, and the Bukharans smoked kalyan and recited the Quran. Kyrgyz lingered around the camp and attempted to trade sheep with us and spoke about their noble ancestors hoping to receive a gift. They came to the caravan accompanied by a large retinue and solemnly asked: Who is richer than all? To them every owner of a tent was a rich man, and thus everyone treated the members of the horde to tea, crackers, dried fruit; the Kyrgyz put all of this in their pockets and quickly withdrew. The caravan had honored the sultan Jangazy, ruler of the Jalair tribe, who was accompanied by his assistant, which was given to him due to his stupidity by the Alatau distinct authorities, and thus named the Kyrgyz assessor.21 The sultan struck us with his eccentricity. He entered the tent walking like a fat goose, which the Kyrgyz use in very formal occasions, sat down in the place of honor and assumed a contemplative look; entirely silent. The sultan suddenly raised his head, quickly looked around the round and uttered a couplet: “The Jalairs have many sheep, Jangazy has many thoughts”, he said and again returned to a Buddhist state. Meanwhile, the assessor and other Kyrgyz were conversing about how the governor-general had arrived to the fortress of Verny,22 and they discussed what he said and what gestures he made. The Kyrgyz all requested us to teach them the “law”, as they take care of our bulls and horses but rarely return them. While the Cossacks know the law they still steal freely and do not care, they say: “the royal man” will pay the bill and he will have to go across “drilled mountains” (what the Kyrgyz call penal labor);23 already we had trouble when three Cossacks perished without a trace; all winter the district assistant and the Vanyushka the interpreter put pressure on Karatal; “confess”, they said: “you killed the Cossacks.” “God save me – I saw nothing at all!” Today the governor says: “You much find the guilty one for me, otherwise I will bend you all into a ram's horn; I, - he says, - thunder and lightning”. The sultan at this time moved his eyes about strangely and occasionally firing off a couplet. After eating pilav24 the guests departed, leaving some kind of almond smell in the yurt.

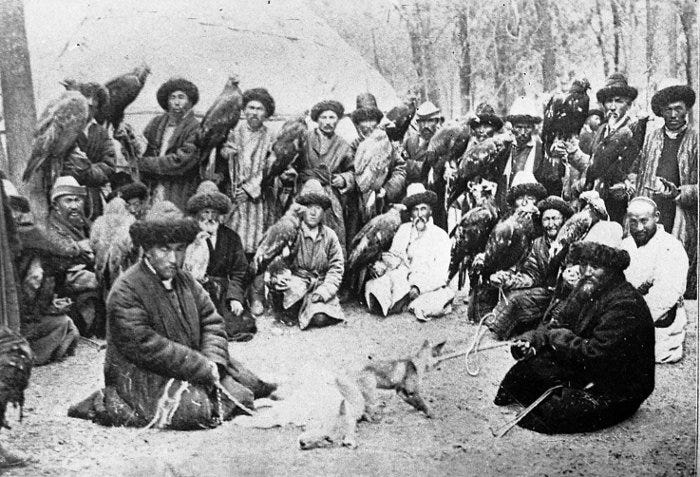

Crossing over the Zungarian Alatau25 through the Jaksy-Altyn-Emel, which is famous for the powerful north-eastern winds that blow across it in the autumn, which is named “ebe”, and is similar to the winds that blow on the southern bank of Alakul,26 - the caravan headed towards the bare flint valley.27 We could see the Ili River in the distance; we went to the Krygyz who handled transportation across the river, and spent the night at a cleft in the sands of Altyn-Emel, between the mountains of Kalkan, where we camped in some kind of gully full of tarantulas, scorpions and camel spiders. For a long time we could not forget that cursed night. We did not sleep at all, and at first light we continued on our march.

The caravan spent two days crossing the River Ili on dilapidated barges. The barges were towed with the help of horses and floated over the river. We celebrated on the shores of the Ili “kurban”, that the caravan had successfully crossed the Suguta, Taraigir and Uch-Merke,28 and reached the Karkara valley,29 after having made 17 forced crossings.30 Here we found the Adabanov Kyrgyz of the Aitbuzum tribe and parted ways towards different auls31 to trade. But the Kyrgyz were in a state of agitation. Before our arrival to the banks of the Kar-Kara, there had been a bloodly fight between the tribes of Kyzyl-burk and Aitbuzum. They expected a Russian official to be sent for investigation after the Kyzyl-burk side complained, while the Aitbuzum had fled in case they were unlucky with the results of the investigation. And so it happened. On the 4th of August the Kyrgyz began withdraw and by evening on the shores of the Kegen and Kar-Kara there was not living soul to be seen, not a sound to be heard, only our sad, lonely tents on the lifeless landscape. For some reason there was an awkward feeling for us. The caravanbashi and some of our old men found that 900 sheep we had received from the Kyrgyz during our trading with them was not enough, and it was decided we would go to the Wild-stone horde. On the 6th of August the caravan reached the Kyrgyz nomads. We were met by Manap32 Karach, the founding ancestor of the Salmeke tribe, who is known by the name Big and is well-disposed towards the Russian authorities and is languishing with the desire to receive the rank of cornet.33 He is called Big because he was as fat and chubby as a bull. Karach wore a pointed white felt hat with the brim cut at the front and back, a cotton wool robe made from strong paper like material with a round collar, similar to our military caftans, and three green silk ribbons on his chest. On his legs were these awkward boots made from red yuft34 with wooden heels. His son was dressed similarly, but his robe was of a brighter color and with a plush collar and sleeves. Karach’s retinue was made up of a few ragamuffins, armed with clubs and spears. One red-haired spearman had only his underwear on, and a felt coat, and other, despite the heat, wore a sheepskin coat and a fur hat. The Kyrgyz spoke very quickly and squeak, constantly pouring snuff35 into their mouths.

The valley of the upper Kegen has a high location and is abundant with food, the bank of the creek is muddy, consisting of hummocky swamps which are called “saz” and are generally found in three mountain valleys: the Kegen, Tekes and Kar-Kara, which are also all places in Zungaria characterized by chernozem36 and thick, densely overgrown grass. In a place with a large amount of “saz” stood wagons of the Kalmyks37 from the IX division, who once camped near the Chinese mine but are now gone. We camped at the River Chalkude; it snowed overnight while the wind howled and swirled with snow, as is winter. It was awfully cold, the blizzard continued for two days, interrupting our business with the Kyrgyz.

On the third day the Kyrgyz tribal leaders arrived to our caravan and brought us to their auls. I and Mamrazyk, my comrade, ended up in the aul of bey Bursyk, elder of the small Kydyk tribe.

Upon arriving to the aul, we went to visit our host. We solemnly approached the doors of the wagon on horseback and asked to enter. The wagon had holes all over its walls and was full smoke. Bursuk sat on the honorary seat, near the wagon’s hearth and facing towards the door; to his right was his wife, an old lady, seated on deer skin, and with her were two daughters and several Kyrgyz women. Even closer to the door stood a boiler, a pot with aryan,38 a bucket, tea cups, plates and utensils. To the left of the doorway sat a Kyrgyz and boots stitched with red yuft, with pieces not without seems after every knot; on the floor scattered about where pieces of wood, pieces of felt, wool and gnawed bones. We were seated on black felt seats with a quilted pattern, seats that also served as carpets. Our host was very friendly, except he regularly cursed the graves of our forefathers, but obviously this was out of habit; his wife would have been even friendlier had it not been for the tobacco in her mouth which prevented her from talking. Bursuk said to give us kumis;39 the hostess pulled out a small, but full jug that had been carefully wrapped within an old robe, and she also took a few wooden cups. As the cups had the remains of some kind of food in them, the hostess and daughters began cleaning the cups with their fingers and putting what they found in their mouths. The children of Bursuk (there were 9) brought us the kumis. I was not without appetite and drank the kumis without paying the slightest attention to the leftovers of the diverse Kyrgyz cuisine that was in the cup, which still thickly covered the inside of the cup. None of this was new to me. In 1856 I was in the yurt of the first rich Kyrgyz man, the supreme manap of Burambay. He had, truly, us siting on a carpet, he himself was on a Bukharan blanket, but his wife also rested on a deer skin. The kumis we drank was from a porcelain cup, but the salty tea was brewed in a washing pan as they lacked any other pot to use. Everything else in the wagon was exactly the same as Bursuk’s: the same pieces of wood, the bones, etc.

For the Kyrgyz, dirtiness is the norm and consecrated as a tradition. They consider washing their dishes to be a sin, no different as spitting on fire, stepping over a mare’s leash as she is being milked, etc. They think that cleaning dishes of their filth will destroy their happiness, destroy their wealth… The men have a habit of not changing their underwear and will wear it until its completely in tatters. Killing lice provides them entertainment in their free time, and they would not know what to do without this pastime; the women are especially fond of this preoccupation and consider it to be the highest enjoyment. While mourning a Kyrgyz wife will not wash her face, will not comb her hair, will not take off or change her dress, even if it is was completely unsuitable to wear.

The hospitality of the Burut patriarch was such that he slaughtered one of his lambs for us. In the yurt he slaughtered the poor lamb despite its tears, cut it into parts, started a fire, set up a tripod and placed a pot on it. The apathetic faces of the Kyrgyz suddenly perked up, the members of the family with exaggerated jealously clambered over the boiling pot, pushing each other aside, and in the end they fought. The hungry dogs crowded around the place where the lamb had been killed, and with fierce appetites they sniffed the floor. The Kyrgyz, in hope of receiving “a taste”, (the guest must, as per Kyrgyz customs, put a handful of meat in the mouths of everyone, otherwise he will be considered ignorant) more and more all filled the yurt. A Kyrgyz artist played on a balalayka40 and sang with a wild voice “doit, doit”.41 In the end the pot was removed, before us was placed a large plate of sliced lamb, with the piece of honor placed on top. We ate the meat, dipping it in salty broth.

The next day early in the morning Bursuk visited us for tea; and he appeared again for lunch; for evening tea and dinner was also not without his presence. He went on to do this every day. The children were not left behind by their father… In general it seemed that feeding the Bursuk family was our legal obligation.

The Kyrgyz themselves consume only milk and beef, the Kydyks, it seems, had the pleasure of seeing trading tents in their aul for the first time. We noted that since our arrival, Bursuk had become very presumptuous. “I will desecrate you father’s mouth!” – he said to his opponent – “I have Sarts42 here, merchants live here” and so on.

More than that, we were visited by women and girls; they brought boiled lamb, kumis and Aryan in jugs, cheese with butter. They give this as according to local customs. My comrade, a very secular person and a reckless admirer of the fairer sex, was happy. He plied them with dried fruit, gave them cotton linen, coral, gave them luxuriant compliments, but, unfortunately, the Buruts understood little and all asked: “What did he say?” His glory thundered even in the distant and foreign auls.

Sometimes in the evenings the daughter of our host would have parties in my friend’s tent. The youth would gather for this, the young women and girls. The women would sit down on one side, and the men on the other. Then begins the game. One of the girls with a wild coquettishness stepped forward and chose one of the boys in the tent that she liked. The overjoyed boy must do some kind of cunning gymnastic trick or sing a song. And neither is entirely easy. The point of the game is that a clever and dexterous boy can receive a healthy and juicy kiss from a girl, and the one who is shamed will be beaten hard. Singing for some reason is preferred over somersaults, but probably not for aesthetic reasons. The process of singing is done in such a way: the singer rests on one knee, and sings some kind of song, mostly of erotic content. The song is sung using a special chant, using an unnatural voice. Starting the first note takes a lot of effort for a Kyrgyz; his eyes turn bloodshot, nostrils expand, at first only muffled sounds make it out, by all appearances unsuccessful until the singer hits the right tone. Other Central Asians will compare the singing of the Kyrgyz with the roar of a donkey, but this is exaggerated. Finishing the song, the singer rises and becomes dos à dos with the girl and with some kind of turn, sneaks a kiss. In general relations between Kyrgyz are primitively unceremonious: mothers, fathers, brothers see this and do not really care, husbands will even encourage their friends to get close to their wives. My caravan friends, it appeared, did not disregard this custom, all the more so as the Buruts are very good-looking themselves. The Buruts, similar to our Kyrgyz, do not know jealously, as characteristic of Asians. What explains this tolerance is that puritanical Islam has not yet spread among these people.

The Buruts call themselves Muslims, but they do not even know who Muhammad was. Funerals, weddings are celebrated with shamanistic rites, but there is a literate Central Asian or Tatar they will force him to read a prayer. It can be said confidently, that no one of this race, starting from the nomads at Issyk-Kul43 to Badakhshan44 itself, knows how to read. The Kyrgyz drink wine which is distilled from kumis, which is a great temptation of the faithful and at every chance they drink. Similar religious concepts were found among the Kazakhs of our Middle Horde 30 years ago. The Russian authorities built a mosque, appointed a Tatar Mullah45 and now, thanks to the influence of the Tatar element, the Kyrgyz of the Middle Horde are not any less fanatical than some of the dervishes of the quiet Mevlevi order,46 who strictly preform 5 prayers a day and fast for 30 days. Some are even begging to introduce harem seclusion.[48] We do not know what would be better for the Kyrgyz steppe: the former ignorance, which did not know religious intolerance, or modern Tatar enlightenment, which was carried out for 300 years in a most anti-progressive way.47

The Tatars in Russia are a complete separate eastern world, they do not have any common interest with Russian narodnost’.48 The big horde is found moving about. Tatars now spread all throughout the horde and have been very successful. Amazingly, while they are even further from the Tatars, the Kyrgyz are less fanatical, although they live under the influence of Central Asian rulers, which we use to consider being nests of savagery. We think that Bukharan mullahs are less dangerous than Tatar ones.

We lived among the Wild-stone horde for almost a month, migrating with them from one place to another, constantly trading our goods for sheep.

Our host, as was already said, did not belong to the manaps, the Kyrgyz aristocracy, nor did he participate in their meeting and instead he was very poor. However Bursuk wanted to have an ancestral legacy and, in order to become rich, he led baranta49 against almost all the Kyrgyz aristocrats. With this he chose for his aul the strongest positions, remote from the rest of nomads. During my time there, his aul was nestled within the impregnable gorges of Muzart (ice mountains) or in the swampy upper reaches of the Tekes River. He did not even have to leave his hiding place. When the other tribes, in full assembly, had assembled their auls in the wide valley of the Kegen River,50 preparing for the baiga celebration feast for the supreme manap of Burambay 90 days after his death, my host with his 9 predatory sons were meanwhile engaged in horse stealing. (…)

During the final days of August, the Kashgar merchants, finishing their affair in the horde, began their return journey. Our Kyrgyz friends advised us to join with the Kashgarians, because the road, in their words, was not safe for a small caravan. The shore of the Tekes River, at Uch-Kapkak, was the meeting point. By the 27th of September there were up to 60 tents at the meeting place, or as said in caravan language, up to 60 fires. Meanwhile, when negotiations were going on between the caravan elders, on which route to take to Kashgar, something happened that suddenly upset our initial plans. The Kokand yuzbashi (sotnik),51 was sent from Pishpek52 to collect zakat53 from the Bugu54 (the Bugu, while Russian subjects, they still paid tribute to Kokand and to China),55 arrived to the caravan with six soldiers and demanded to be paid. He (a Bugu) asked: what fee and for what? The yuzbashi was offended, he herded off 300 sheep and after driving up a mountain, he began to solemnly guard his prey.

The Kashgarians, accustomed to fighting during the uprisings against China, grabbed a few stakes and rushed at the Kokand soldiers and with unusual agility threw them off their horses, and then they beat the soldiers so brutally that one Kokandi was left breathless. The Kyrgyz, probably afraid of Tashkent seeking revenge against them,56 told the Kashgarians they would let them go until the health of the wounded soldier improved. We had no involvement in the brawl, because, together with the Tatars and a few other Kashgarians, we had hastily left for a trek in the mountains before it started snowing. Our caravan was made up of 10 fires and the number of people had increased to 60. At the top of the Tekes we went over the Santash mountain pass,57 which is a flat plateau and known for the legend about Tamerlane, then we went through the low mountain Kyzyliya and departed from the valley of the river Dzhityugus (happiness); we camped here for the night and the next day our journey went along the flat and fertile valley of the Terskey, where half-naked Buruts were working in the fields. On the river Dzhityugus we found old friend Bursuk, who along with kydyk tribe had migrated here to collect bread, and few more auls subject to the bey Samsala and the famous predatory Dzhanet. We said goodbye to the aul with Bursuk and took him as our guardian, and on 9th of March we exited from the Zaukin gorge.

However, the presence of Bursuk did not save us from the predatory Kyrgyz. On the 11th, when the caravan was going through a narrow gorge littered rocks, which Mr Semenov58 wittily and prophetically called a natural barricade, suddenly behind us rose a deafening cry and flying banners. We barely managed to take defensive positions and fortify these barricades, as we soon came under attack by a gang of 70 Kyrgyz. Our comrades, who were guided by commendable sense of self-preservation, took cover behind the camels and kept their heads down. Meanwhile, thanks to our well-defended position and superior arms, our servant were able to repel the Buruts and even take one of their leaders as prisoner. The affair was limited to injuries on both sides and an exchange of prisoners. The honorable Bursuk, taken by us for protection, considering himself compromised, secretly departed without even accepting a gift from us, which we had promised him. (…)

The gorge ended with a steep cliff around 800 sazhens59 tall. The skeletons of different animals covering this steep cliff testified to the difficulty of overcoming it. (…) The caravan as whole could not climb the cliff in the course of a day and one part of it camped on a small swampy plateau which constitutes the end of the Zaukin pass, and the other part remained at the previous night’s camp. Snow, falling in abundance, greatly increased the difficulty of the climb. The pack horses and especially the camels frequently slipped along the wet rocks, with some falling and rolling down the cliff, making a roaring sound that echoed as they fell. Thus died five camels and two horses. My companions seemed absolutely confused. Everyone thought only about escorting our remaining pack animals safely to the top. The cries of the animal drivers, their abuses and curses, pious calls to Allah, Bahavedin, Apak-Khoja and other Muslim saints echoed and shook the century’s old snow on the surrounding mountains.

Kokand is a city in the Fergana Valley, modern Uzbekistan, and was the capital of the Kokand Khanate, a powerful region state in Central Asia in the 18-19th century

Bento de Góis

German Botanist and explorer. Adolf, and his brothers Hermann and Robert, were commissioned by the British East Indian Company to study the earth’s magnetic field in Central Asia

The province of Xinjiang, or “New Land”, was only formed in the 1880’s

Ancient Greek geographer and astronomer, from the 2nd century AD, lived in Alexandria

Town on the border between the Russian and Qing Empires (Outer Mongolia & Trans-Baikal/Buryatia). For awhile, Kyakhta was the only place where Russia could trade with China

Port cities where British and other Europeans enjoy extra-territoriality and special trade rights with China

Marco Polo mentions something similar about the women of the Tarim Basin

“цыган (мультани и лулу)” in the text. I do not know what these two words mean, likely two types of gypsies

The Khojas were an Islamic, land owning, ruling caste found across Central Asia and the Tarim Basin’s cities. The term is roughly equivalent to “lord” in English

After being conquered by the Qing, Kashgar had been quite restless due to the ruling Khojas and their connections to the Kokand Khanate in the Fergana Valley. For more on these political dynamics, see “The Rise and Fall of Khoqand” by Scott C. Levi

Original text says “одного за то, например, что он служил чиновником при китайском правительстве, другого за то, что зевнул, третьего за то, что он черногорец.” Why the second and third were killed is not at all clear. “Yawning” and “black mountaineer” likely refer to something local to Kashgar

The Bukhara Khanate, another state in Central Asia, in modern day Uzbekistan

Something akin to a hotel or hostel, but for caravans and their staff

Leader of the caravan

“Horde” refers to a large tribal nomadic grouping. The Wild-stone Horde reference to the Kyrgyz tribes in the Tianshan Mountains

Old Russian unit of measurement, equivalent to 1 kilometer

Located north-northeast of Almaty

Modern day city of Semey, on the Irtysh River in northeastern Kazakhstan, near the Russian border

Rubles are Russian currency

“поэтому называется киргизами заседателем” in the original text. Jangazy was likely empowered by local Russian authorities to handle legal disputes among the Kyrgyz, but likely his assistant was the real authority

Modern Almaty

My translation here is partially guesswork. I assume what is meant is that anything stolen from the “royal man” (the state) will be paid for by with taxes, the labor off state peasants or by “katorzhniki” – convict laborers. The original is this: Вот казаки знают закон, ну и притесняют, воруют свободно, тягаться с ними, говорили они, не приходится: «царский человек» на счету состоит, за него как раз пойдешь через «сверленые горы» (так киргизы называют каторжную работу)

Central Asian food, rice with carrots, raisins and lamb

Mountain range on the modern Kazakh-Chinese border. The range is between Zharkent and the Alaqol Reserve

Likely the Alaqol Water Reserve

Original text says “караван вышел на голую кремнистую долину”. I have no idea where “bare flint valley” is located

These are mountains I believe

Karkara Valley is located from Kazakhstan to Krgyzstan, from the Tekes River Valley towards Karakol on Lake Issyk Kul

Over rivers and mountains

Word for village, common in Central Asia and Caucasus

Manap was a ruling title for the elite among the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. Similar to Khoja among the Tarim Basin’s cities

Also known in English as “standard-bearer”. Equivalent to lieutenant in modern armies

Russian leather, unique from other leather as it was made with birch oil. In previous centuries it was widely exported and known for its quality

A tobacco product, usually sniffed, common throughout the 19th century

“Black earth”, which is distinct for its excellent nutrients making it excellent for agriculture. Also found in Ukraine, northern Manchuria, etc

Tribal grouping within the Western Mongols that defected from the Oirat Zungar Khanate and migrated away

Dairy based drink common throughout Central Asia, Mongolia Persia, etc. Also known as Doogh

Drink made from fermented horse milk

Musical stringed instrument

«доит, доит» I am unsure whether this is Russian, Krygyz, or some other language

Local word for farmers

Large lake in Kyrgyzstan. The Buruts were located just to the east of it

Mountainous region in the Pamir Mountains. Modern day eastern Tajikistan

Russian imperial state converted steppe nomads to Islam, “For Prophet and Tsar”

“дервишам кувыркательного ордена Мевлеви” I had difficulty translating the word “кувыркательного”

This was also tricky to translate. Seemingly Valikhanov prefers Europeanized modernization over either nominal or “fanatical” Islamic adherence. Original says “Мы не знаем, что было бы лучше для Киргизской степи: прежнее невежество, чуждое религиозной нетерпимости, или современное татарское просвещение, выражающееся в продолжение 300 лет самым антипрогрессивным образом”

Literal translation is something like “national-feeling” or “nationhood”. I did not translate it due to the term’s historical and polemical relevance for the era

Kazakh/Kyrgyz term for stealing animals from others

Near the Tekes River, at the modern Kazakh-Kyrgyz-Chinese border

“Yuzbashi” was a Turkic title, equivalent to captain. “Sotnik” was the Cossack equivalent (meaning “one hundred-person)

Modern day Bishkek, capital of Kyrgyzstan, which was then a Kokand fortress

Islamic tax/charity, paid to support other Muslims

A Kyrgyz tribe

This is likely because none of these empires maintained strong authority in the remote mountains of Central Asia, as the merchants frequented each empire it only made sense to pay tribute to all three

Tashkent was then apart of the Kokand Khanate. These Kyrgyz probably had trading relations with Tashkent

From the Kar-Kara River Valley to Lake Issyk Kul

Probably Pyotr Semenov-Tianshansky, Russian explorer of the Tianshan Mountains

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.13 meter or 7 feet

This was fascinating. Thank you for posting. Did Valikhanov ever meet any British agents / adventurers in his travels?