Our Middle Asian Frontier with Kashgar - Niva, 1879

Translation about the former khanate of Yakub-Bek and the veiled lands beyond Russia's frontier in Middle Asia

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

This is my first paid post. In addition to everything that I already post here, I aim to post a pay-walled translation once a month, or at least every six weeks. These posts take a lot of time to put together, so I will do my best.

The regular two posts a month or so that I try to put out will remain free, in addition to other things I post. I will try to make sure that pay-walled posts are longer than the usual translations that I publish. I have a huge number of lengthy and interesting Russian texts saved and this will serve as good motivation for me to work on them.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber, your support will make it easier for me to continue publishing my work here and on X/Twitter, as well as further books that I hope to publish. With sufficient support I will be able publish work at an even higher volume!

I greatly appreciate all support and readers, thank you!!!

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of an article about Kashgar and Yarkand, published in the journal “Niva,” №12, 1879. The source for this translation can be found here. The original text can be found here (starts on page 218/219 of the PDF). Niva was as a weekly illustrated journal which ran from 1870 to 1918, and was the most popular Russian journal from that era. The exact author is unknown.

Kashgar and Yarkand are the two largest cities in the western end of the Tarim Basin, the vast desert region located to the northwest of China, which connects it to the rest of Eurasia. Enclosed by mountains on all sides, the Tarim is centered around the Taklamakan Desert, whose name roughly translates to “go in and you will never come out.” But on the edges of the desert two chains of oases run along the breadth of the basin, with one branch in the north and the other in the south. Both north and south routes meet at Kashgar and Yarkand, from where trade routes either go west to Central Asia and Persia via the Irkeshtam and Torugart passes, or to India via Tashkurgan and the Karakoram passes.

The Russian Empire first approached the Tarim Basin in the 1850s after expanding into the Tianshan Mountains which stand northwest of the basin. Despite lying just beyond Russian-Chinese frontier in the Tianshan and Pamir mountains, the Tarim Basin, which then was known under names of Chinese Turkestan, Eastern Turkestan or simply as Kashgaria, remained shrouded in mystery for quite some time. A distant and unstable region under China’s Qing Dynasty, Beijing maintained great secrecy over the region and did its utmost to limit Europe’s ability to penetrate it. Even in ancient times Greco-Roman knowledge of the world largely halted at the Imeos Mountains, the name which the Tianshan-Pamir region was known under. And even as Russia pushed deeper into Asia in the 1860s and 1870s, the Tarim still remained largely terra incognita due to the years of war which ravished it during the era of Yakub Bek. Only local Central Asian merchants, who sometimes were Russian spies, had easy access to Kashgaria, and it is largely from them the Russia learned anything at all.

Some notes for further reading:

For more on Yakub-Bek’s state and his downfall, I would recommend “Holy War in China” by Kim Ho-dong. For more on the diplomatic contact between Britain and Yakub-Bek, which the article below mentions briefly, see “Visits to high Tartary, Yarkand, and Kashgar” by Robert Shaw, who met Yakub Bek in 1869, as well as the writings by Sir Thomas Douglas Forsyth: “Yarkand (Forsyth's mission)” and “Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T.D. Forsyth : with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the ameer of Yarkund.”

The article also mentions a Boulger who wrote about Yakub-Bek. This refers to Demetrius Charles Boulger and his book “The life of Yakoob Beg; Athalik Ghazi, and Badaulet; Ameer of Kashgar.”

Despite Russia’s aggressive nature in Central Asia, Kashgar and Chinese Turkestan only became targets of Russian/Soviet designs under Stalin, who backed several local uprisings amongst the Uyghurs in hopes of eventually taking over the region and Sovietizing it as a puppet state. A good book on this topic is “Uyghur Nation” by David Brody.

The term “Middle Asia” was often used by Russia to refer to the part of Central Asia which it conquered. The term “Kokandtsy” is simply the literal transliteration for the Russian word for “Kokand people,” which I used in lieu if “Kokandis.”

Many of the illustrations below were originally published with the article in Niva. These drawings were made by C. DeLort and engraved by C.H.Barbant.

Our Middle Asian Frontier with Kashgar

Not long ago from our own time, Middle Asia with her khanates was still a region almost completely unknown to Europe. It was as if the region was separated from Europe by some sort of fantastical wall, a terrible frontier that few had been able to see beyond. But the mystery attracted all with irresistible force. And here, we will see that bold travellers have reached those distant countries, like Marco Polo, the Jesuit Ges1 and others. Many of them laid their heads down there, while others returned home and brought with them information about the places they had visited. In the mass of the so called educated public, this information is either rarely known or was forgotten long ago. We went there and fought. But lone travellers, pilgrims of science, turned out to be happier: until recently nearly none of our expeditions had been successful: we remember our Khivan expeditions under Peter the Great, Bekovich-Cherkassy, and then under the one under the previous Tsar led by Perovsky. We remember the Afghan expedition by the British in 1839 to 1842, and others. The Middle Asian wall remains standing, motionless, guarding access to this forbidden land. In the end, not long ago, we pierced through this barrier and before us opened an entirely unseen country…

Now research continues on a wide, smooth path and it goes without halting. We have made use of material that we obtained to acquaint the readers with a part of Middle Asia, which until now, we knew little about - Kashgar.

In 1877, during the very peak of the historical struggle, we turned our attention to the tragedy that was playing out in the theater of war which was then near to our eastern frontier. This tragedy can be titled in the historical chronicles under the heading: “The Fall of the Kashgar Khanate.”

Although this khanate has only just collapsed, the history of its rise, existence, its form of government, outlines of construction, and finally, the conditions and way of life of its population, all of this, taken together, characterizes a singular type of Middle Asian state, many of which are still “flourishing” even today. Kashgar is of particular interest to us, not only as a country which serves as a new point of contact with the Chinese, but also as a country where Britain has turned its friendly attention towards…

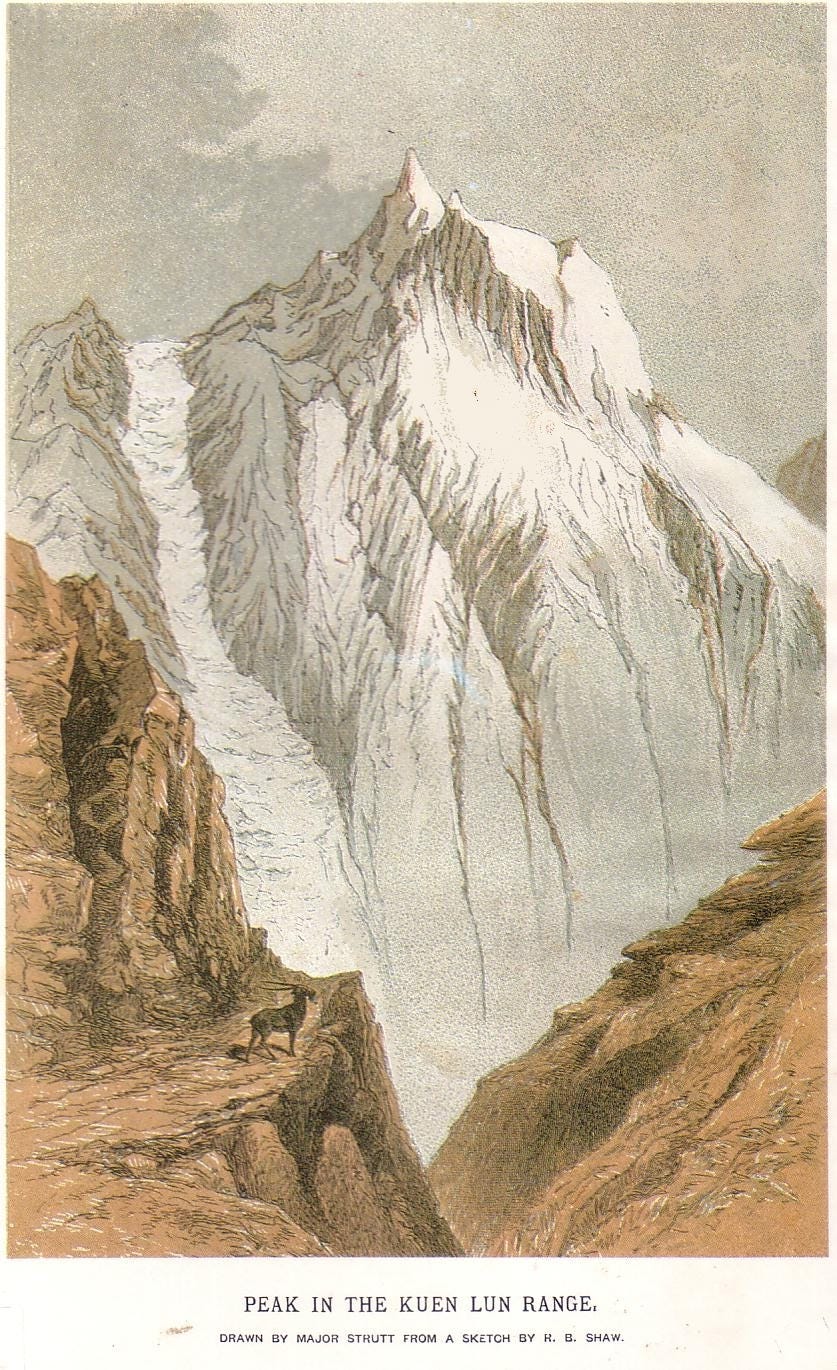

Kashgar, or as some call it, Eastern Turkestan, is the region which sprawls from Siberia to Kashmir, from the Pamirs to the former boundaries of the Chinese Empire (since 1877, as is known, the former khanate is now apart of this empire). The character of this country is primarily mountainous. The spurs of the Tianshan, Karandag, Pamirs, Musdach, Kunlun embrace this country and cut it off in all directions, and in places, form picturesque valleys.

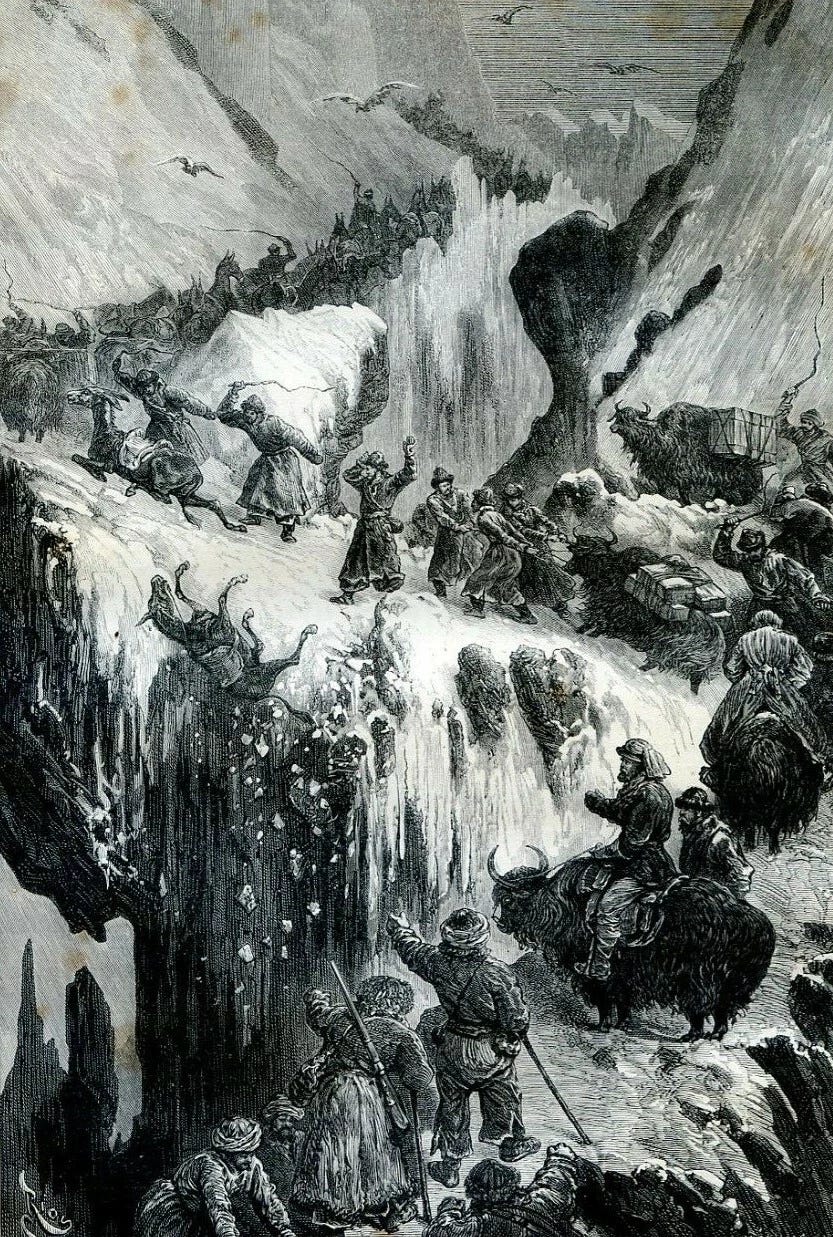

But the routes through these valleys, in large part, go though these mountains, through valleys and precipitous gorges that often rise to a few thousand feet above sea level. In order to have an understanding of the difficulties which accompany a crossing of these gorges, we can give a retelling of a story by one of the members of the British embassy that was sent to Yakub Khan, not long before his fall.

The embassy had to cross the Sandzhunsky gorge (to the south of Kashgar), at a height of 6000 feet. “The road,” he says, “was unusually difficult. For example, we had to make our way along such a narrow defile, that at times only one yak could go at a time (the embassy travelled and carried their baggage on yaks, mules and ponies), then we came across huge stones blocking our path, covered in a sheet of dazzling white snow and formed a wall of sorts, 3000 feet in width…”

The envoy ordered people forward, and had them make notches on the ice and threw carpets, blankets and fur over them.

“…Many of them (mules) broke off and plummeted to their death: one mule plunged into the abyss and fell at least 400 meters…”