Tamim ibn Bahr's "Journey to the Uyghur Khaganate"

Exploring the only Primary Source on the Uyghur Khaganate and their capital Ordubaliq

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

This is a follow up to my other essay on Substack on the Collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate. This article is posted both as a continuation of my research on the ancient Uyghurs, and because nowhere else online can Tamim ibn Bahr’s text be read. Along with the text itself, I have added my own introduction and an commentary & analysis further below.

Introduction

Tamim ibn Bahr visited the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 821, when the ancient Uyghurs were at the height of their imperial power. Uyghur armies had just successfully campaigned against the Karluks in the west, raiding as far as Sogdia in Central Asia. Elsewhere, Uyghur armies had forced the Tibetans to go on the defensive in the Tarim Basin, and in Siberia they had contained the Yenisei Kyrgyz north of Tuva. The Uyghurs also enjoyed predominance over China’s Tang Dynasty. The Chongde Khagan had recently married an imperial Chinese princess, and the Khaganate continued to enjoy an unequal and exploitative economic relationship with Tang China. In the year of Tamim’s journey, the Uyghur Khaganate was at the height of its territorial expansion and economic-political dominance on the Silk Road.

Of the last 2000 years, the early medieval period (6th – 9th centuries) is by far the least documented, the most mysterious, but yet the most decisive in the formation of the modern world. It was during this era that the world of Antiquity and Roman civilization came to a conclusive end at the Battle of Yarmouk and was replaced in the east by the world of Islam. In the West, Europe was being reconfigured into its current Faustian civilization1 by the Germanic Goths who had torn down the late-Roman Empire and come to occupy its lands. In the north, the Turks and Russia both emerged at opposite ends of Eurasia in the 6th and 8th centuries, respectively. It was in this period that our modern world was born, and whatever survived from Antiquity and before has merely come down to us as vestiges of a lost world.

Yet, despite how immensely formative this early medieval period was, its history remains largely a mystery. Much of what occurred was never written down and recorded, and much of what was recorded was lost, either destroyed or forgotten across time. In the case of Central Eurasia during this period, much of what was once known was stored in libraries across Transoxiana and in Baghdad, but all of this was annihilated by the world-destroying Mongols in the 13th century. All that survives today are ruins and a handful of written sources, and as a result, our historical knowledge of this era is largely based on fragments. All that exists on the rise of Islam is the Koran, which as an objective historic source has dubious value. After the catastrophe at Yarmouk, Byzantium became mired in its Dark Age, with only the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor and a few other sources documenting what transpired. For the Rus’ and ancient Turks, only the Russian Primary Chronicle and the Orkhon inscriptions tell us the earliest histories of these peoples. For many of these states and peoples, our only historical sources for them come down to us from Arab travelers.

The writings of these Arab travelers constitute some of the best historical sources of the early Middle Ages, as they record fascinating geographic, ethnographic and historical observations. The most famous of these Arab travellers is Ahmed ibn Fadlan, who travelled from the Abbasid Caliphate to the Volga Bulgars in the 10th century, and wrote a fascinating account of the Oguz Turks, the Turko-Jewish Khazars, the Vikings, and the forest dwelling peoples of the far north. Notable others include Sallam the Interpreter, Al-Maqdisi, Ahmad ibn Rustah, and Tamim ibn Bahr. However, these Arab accounts are moreso anecdotal than comprehensive histories. Only the history of China’s Tang Dynasty is well documented in this era.

In eastern Eurasia, a millennium long dance between China and nomads on the steppes had culminated with the duopolistic hegemony of China’s Tang Dynasty and the Turkic Uyghur Khaganate. China, representing the world of settled agriculture and high civilization was contrasted by the steppe nomads, whose way of live was both formless and rootless. They came to represent antithetical values in relation to one another, but retained close military and cultural connections despite this, and while their relative balance of power changed over time, their combined wealth and power facilitated Silk Road and allowed it to flourish.

The Tang Dynasty reunified China in the early 7th century, and rapidly conquered the nomadic steppes, the Tarim Basin, and reached out as far as Samarkand in the West. The Turkic nomads on the steppes to the north later threw off Tang dominion, but remained in an inferior state compared to the Tang until the mid-8th century. By the 750’s, Tang power was supreme over eastern Eurasia, but this belied a growing malaise within the court and festering crisis brewing on the northern frontier. Tang China at its imperial apotheosis was broken by the rebellion of An Lushan, a Sogdian-Turk general employed by the Tang who led his armies south against the empire. By the middle of 756, An Lushan had pushed aside all opposition, scattering the Tang’s armies and swiftly occupied the imperial capital of Chang’an. In response, the Tang formed an alliance with the Uyghur Khaganate, the Turkic nomadic empire on the steppes to the north.

The Uyghurs agreed to intervene on behalf of the Tang Dynasty in exchange for the establishment of a political-economic relationship with the Tang that greatly favored the Uyghurs, and enormously enriched them at the Tang’s expense. The Uyghurs were able to maintain this unequal relationship with the Tang for the reminder of their Khaganate, until 840 when their capital Ordubaliq was sacked by the Yenisei Kyrgyz, which sent the Uyghur tribes in flight off the Mongolian Plateau.

While the history of the Tang Dynasty is quite well documented by ample amounts of primary sources, all thanks to China’s strong literary culture, the history of the Uyghur Khaganate is far less documented. As nomads, the Turkic Uyghurs simply did not have the same literary culture as China, and as a result, primary sources on the Uyghurs are severely limited. The only primary sources that exist are limited archeological sites in modern Mongolia and Tuva,2 Tang Chinese writings on the Uyghurs that were written from afar in Chang’an,3 and lastly, Tamim ibn Bahr’s “Journey to the Uyghurs”.

Tamim ibn Bahr was a Muslim Samanid envoy who traveled to the Uyghur Khagan in 821. Tamim departed from the Syr-Darya River, traveled through the steppes, and arrived at the Uyghur capital of Ordubaliq, located in modern day Mongolia, west of the modern capital of Ulaanbaatar. Personal details on Tamim’s life and what the exact purpose of his mission was are unknown, but some speculations can be made. His text is short and sparse on details, but due to an overall lack of primary sources Tamim’s account is thus very important, simply because it is all we have. As mentioned above, Tang Dynasty sources on the Uyghurs were written in China by court historians who worked off imperial reports. Chinese sources were written by people with second hand knowledge of the Uyghur Khaganate, and as historical sources they are fragmented and often opaque in detail. Readers of Colin Mackerras’ translated and compiled volume “The Uighur Empire according to the Tʻang Dynastic Histories” will be able to see as much. Thus, the importance of Tamim ibn Bahr’s “Journey to the Uyghurs” is that it is the only truly primary written source that exists on the Uyghur Khaganate and its capital of Ordubaliq.

It is believed Tamim ibn Bahr was an envoy for the Samanid Dynasty, the first indigenous Islamic dynasty in Central Asia which emerged from the fragmenting Abbasid Caliphate. The Samanid Dynasty was founded by the ibn Asad family, who had their origins in the Balkh region before converting to Islam and serving as governors of Khurasan under the Abbasids.4 The seat of the dynasty was first located in Samarkand, and then later moved to Bukhara, both in the Zerafshan Valley, the former heartland of Sogdia. Along with agriculture and the mining of rare gems in the Pamir Mountains, the economy was primarily based on the slave trade. The Turkic nomads on the steppes would capture and sell each other as slaves in Samanid markets. From there, the slaves were then transported and sold across the Islamic east.5 Many of these Turkic slaves would be purchased as soldiers, and overtime, the armies of Muslim states would be increasingly dependent upon Turkic “gulam” slave soldiers. These slave soldiers would overthrow their masters and establish states of their own, such as the latter Ghaznavids who succeeded the Samanids. Additionally, the Samanids initiated the Islamization of the steppe nomads through both missionaries and trade ties. Two centuries later as the Samanid Dynasty was faltering, the Islamic Turkic Karakkhanids would conquer Central Asia and Turkicize the region in turn.6

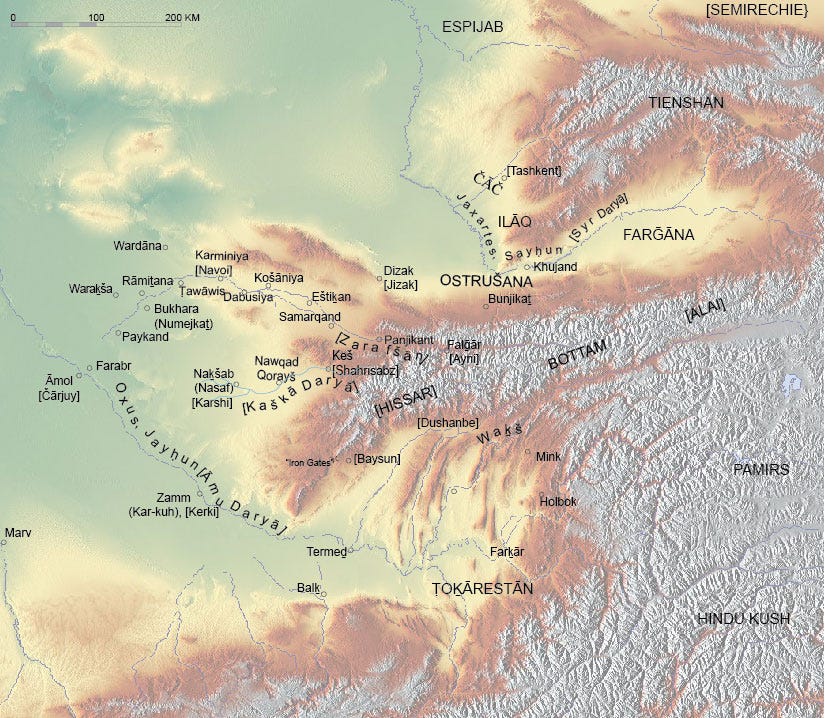

Tamim ibn Bahr’s journey occurred in the immediate aftermath of the Uyghur invasion of Sogdia and northern Transoxiana in 821, during their pursuit of the Karluks. The Uyghurs and Karluks were two distinct Turkic nomadic tribal groupings who had been subordinate to the Second Turkic Khaganate. These two tribal groupings, along with the Basmils, allied in rebellion and overthrew the Khaganate in 742. The Uyghurs, Karluks and Basmils then battled for hegemony over the steppes, with the Uyghurs emerging victorious and sending their two former allies in flight westwards. The Karluks eventually relocated to the region of Zhetisu, also known as Semireche,7 in modern day southeastern Kazakhstan, the region around today’s city of Almaty. The Uyghur Khaganate and Karluks remained in off-and-on conflict for the next hundred wars, with the Karluks allying with the Tibetans and Yenisei Kyrgyz who were also enemies of the Uyghurs. This conflict eventually culminated with a Uyghur invasion of the Karluk homeland, prompting the highly mobile nomadic Karluks to flee. The Uyghurs pursued the Karluks westwards over the Syr-Darya River and reached as far as the Fergana Valley.8 In the process of this campaign, the Uyghurs raided the Sogdian kingdom of Usrusana, modern day Istaravshan, Tajikstan.

The Uyghur invasion of northern Transoxiana (Central Asia) likely caused great panic among the Muslims of the region. The Arabs had only entered into Transoxiana in force after 717, and soon came into conflict with the Turgesh, a Turkic tribal grouping that had occupied the Zhetisu region prior to the Karluks. For the next three decades Central Asia was made into a wasteland as the Arabs attempted to subdue the local Sogdian city-states, and the Turgesh intervened on the Sogdians’ behalf to fight the Arabs. Major conflicts between the Arabs and Turgesh occurred in 721, 724, 737, and 741. This conflict between the Arabs and Turks over Sogdia climaxed at the Battle of Talas in 751, where the Arabs fought a great battle against the empire of Tang China, whose army largely consisted of Turkic cavalry fighting under the Tang banner.

The Turgesh Turks had often allied with the Tibetans against the Arabs. The Tibetans regularly crossed the Pamir and Hindu Kush Mountains, and attacked the Arabs in Tukharistan, ancient Bactria and modern Tajikistan. Just prior to Tamim’s journey, the Arabs had campaigned against Tibet in 815 and 816. The Arabs invaded the Hindu Kush Mountains of modern Afghanistan, and forced the king of Kabul to submit and convert to Islam. After, they invaded the Wakhan corridor and raided as far as the Kingdom of Balur in the Karakoram Mountains, modern day Gilgit in Pakistan. Kabul and Balur were both aligned to Tibet. Thus, the Arabs were reasonably concerned about the arrival of the Uyghurs to their northern frontier.

In all likelihood, Tamim’s mission to the Uyghurs was for three purposes. Firstly, to ascertain the Uyghur Khagan’s disposition towards the Arabs, and determine whether the Uyghurs were a significant threat. Secondly, for commercial purposes. Tang China was the main economy on the Silk Road and the largest producer of goods that were exchanged across Eurasia. But as a result of the An Lushan Rebellion, the Tang had withdrawn its armies from Central Eurasia, which left a void that was eventually filled by the Tibetans in the southern Tarim Basin and the Uyghurs in the northern steppes. Additionally, the unequal economic relationship between the Uyghurs and the Tang Dynasty effectively made China subordinate and dependent upon the Uyghurs. Ironically, despite the Tang’s much weaken state after the rebellion’s conclusion, trade flows out of China only increased due to Uyghur extraction. The Uyghurs sold the excess silk and other goods further west, stimulating Silk Road trade. Thus, the Uyghurs came to dominate both China and most of the trade routes running from China to the West, making them the most important economic-political power on the Silk Road at the time. The third purpose, possibly the Uyghur Khagan wanted to secure the rights of Manicheans living under Arab rule in Central Asia, and hoped to negotiate an agreement that Manicheans and Muslims would be respected in each other’s realms. Of course, all of this is just speculation. All that can be said for certain is that Tamim’s mission was very important, as the text below indicates.

To clarify, below is not my own translation, but the work of Vladimir Minorsky, the famous scholar of Persian history. Minorsky was born in 1877, in the former town of Korcheva near Tver. Prior to the First World War, he served in the Imperial Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was posted in Persia. After the Bolshevik Revolution he emigrated to Paris.

My reason for posting a copy of Minorsky’s translation of Tamim ibn Bahr’s here is that it cannot be accessed anywhere freely. It can only be read online through Jstor. As a physical text it is only available in the “Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 12, no. 2 (1948): 275–305.” Generally speaking, there is almost no information on Tamim ibn Bahr freely available online, not even an entry on Wikipedia. The translated text of Tamim ibn Bahr’s account can only be read freely online here. Below is the text, and further below is additional commentary clarifying certain points of interest within the text. I have copied everything that was written by Minorsky, without any changes or alterations. My only additions are the footnotes explaining words for benefit of the reader.

Tamim ibn Bahr’s Journey to the Uyghur Khaganate, Translated by Vladimir Fyodorovich Minorsky, 1948

1. Tamim b. Bahr al-Muttawwi’I reports that their (i.e. the Turks’) country is very cold and one can travel in it (only) during six months of the years. He says that he journeyed to the country of the Tughuzghuzian khaqan on rely horses which the khaqan sent him and that he was traveling three stages (sikak) in a-day-and-a-night, travelling as hard and as fast as he could. He journeyed twenty days in the steppes (barari) where there were springs and grass (kala) but no villages or towns: only the men of the relay service (ashab al-sikak) living in tents. And he was carrying with him twenty days’ provisions. This because he knew the affairs of that country (madina), and that the distance was twenty days along the steppes with (only) wells and grass. And then, after that, he traveled twenty days among villages lying closely together and cultivated tracts (imarat). The people, all of them, or most of them, were Turks, and among them were fire-worshippers professing the Magian9 religion, and Zindiqs.10 After all these days he arrived at the king’s town.11

2. He reports that this is a great town, rich in agriculture and surrounded by rustaqs full of cultivation and villages lying close together. The town has twelve iron gates of huge size. The town is populous and thickly crowded and has markets and various trades (tijarat). Among its population, the Zindiq religion prevails.

3. He mentioned that he estimated how far it was (thence) to the country al-Sin12 and he understood it was a distance of 300 farsakhs,13 and he added: “I think it is (even) more than that.”

4. He reports: “to the right (south) of the town of the king of the Toghuzghuz are the (lands) of the Turks with whom no one else mixes; to its left, the lands of the Kimek;14 and straight ahead, the country of al-Sin.”

5. He says that from (a distance of) five farsakhs before he arrived in the town (of the Khagan) he caught sight of a tent belonging to the king, (made) of gold. (It stands) on the flat top (sath) of his castle and can hold (tasa’) 100 men.

6. He records that the khagan, king of the Toguzoguz, is related by marriage to the king of China (al-Sin),15 and the latter is sending him yearly 500,000 (pieces of) silk.

7. He also reports that between Upper Nushajan (Barskhan) and al-Shash (Tashkent) – via Taraz – there are forty stages (marhala) for caravans, but he who journeys on horse-back (ala dabba) by himself, crosses that distance in a month.

8. He says that in Upper Nushajan16 there are four large towns and four small. He estimated the number of warriors in one town lying on the bank of a lake (which is) there and put them at about 20,000 fully armed horse. There is no one stronger than they among all the Turkish tribes. When they gather for war with the Kharlukh,17 they are a hundred and the Kharlukh a thousand, and this they come out in all their wars.

9. He reports that this lake18 is like a square-shaped pond and around it are high mountains, with all kinds of trees in them. He says: “and here are traces of an ancient town. I could not find among the Turks anyone knowing its story: who built it, who were its people and when it became ruined?” On the site of it he inspected a river which crosses it. One cannot reach its bottom here: “and I saw in it various sea-creatures (haywanat) which I had not seen before. And I also saw birds the like of which I had not seen in any of the countries.” He says: “The people of al-Nushajan and others from neighboring towns and villages circumambulate (the site) once a year in the spring and they do this as a kind of religious rite (‘umran). He says: water enters (the late) from the direction (nahiya) of Tibet in 150 streams (nahr), large and small, and also from the direction of the Toghuzghuz and Kimak.

10. He says that its (?) length is a journey of forty days on camels, but a horseman can cover (the distance) in a month if he rides hard (idha jadda fil-sayr).

11. He says that he found the king of the Toghuzghuz when (he travelled) to him encamped in the neighborhood of his town and he estimated his army, around his tents (saradiq) – to say nothing of the others (duna ghayrihim) – and it was some 12,000 strong. He says: and after (besides ?) these (there are) seventeen chieftains (qa’id), each having 13,000, and between each two chieftains there are offices (or military posts?) consisting of tents. The chieftains jointly with those who are with them in the offices (military posts) form a circle round the army (‘askar). In this circle there is a gap (gaps?) to the size of four gates (opening) towards the army. He says: and all the animals (horses) of the king and the army (reading: al-jaysh for al-jayyid) pasture (tar’a) between the tents of the kind and the places occupied by the chieftains, and not one animal escapes outside the camp (al-‘askar).

12. And we asked him about the road to the Kimak (and he said): from Taraz (one travels) to two villages called K.wak.b19 which are flourishing and populous. Their distance from Taraz is seven farsakhs, and from this place (to the residence) of the king of the Kimak a hard rider carrying his provisions travels eighty days. These deserts, steppes, and plains are vast and abound in grass and wells, and in them are the pastures of the Kimaks. He says that he travelled that way and found the king and his army in tents, and in his neighborhood were villages and cultivated tracts (‘imarat). The king travels from one place to another following the grass. His animals are numerous and with tiny hooves (daqiqat al-hawaur). He reckoned those in the army and found they were some 20,000 horse.

13. Abul-Fadl al-Vasjirdi reports that twice in the days of (Harun) al-Rashid (786-809) the king of the Toghuzghuz led an army against the king of China (al-Sin).20 But it is (also) said to have been in the days of al-Mahdi (775-785).This (?) campaign took place between Surushana21 and nearer to (ila) Samarqand.22 The governor of Samarqand fought him on several occasions and some of the fighting was heavy. (God) granted victory to the ruler (sahib) of Samarqand over him and he defeated him and killed many of his companions. It is said that he had 600,000 (warriors), horse and foot, of people of China.23 The Muslims took an enormous booty and captured some people whose children are those who fabricate in Samarqand good paper and various kinds of arms and implements. These are produced only in Samarqand of all the towns of Khorasan.

14. And of the wonders of the country of the Turks are some pebbles they have, with which they bring down rain, snow, cold, etc., as they wish. The story of these pebbles in their possession is well known and widely spread and no Turk denies it. And these (pebbles) are especially in the possession of the king of the Toghuzghuz and no other of their kings possesses them.

15. Abu ‘Adbillah al-Husayn b. Ustadhuya told me from Abu Ishaq Ibrahim b. al-Hasan, from Hisham b. Lohrasp al-Sa’ib (?) al-Kalbi, from Abu-Malih from Ibn ‘Abbas, as follows: Abraham, on him be peace, did not marry except Sarah, until she died (Gen. 20-1), and then he married a women from original Arabs called Quntura (Gen. 25, 1: Keturah) bint Maqtur. And they started travelling until they settled in a place in Khorasan where they multipled and under this name (?) they subjugated all those who resisted them. Their story reached the Khazar who were descended from the son of Japhet, son of Noah. They betook themselves to them and made a pact with them and intermarried with them. Some of them stayed with them and the remainder returned to their country.

Analysis and Commentary

As pointed out by Minorsky, this text is likely the record of an interview with Tamim. The repeated use of the phrases “he said” and “we asked him” indicate that is an interview or a conversation between Tamim and either a state official or a scholar, with the later questioning Tamim on his journey.24 It also likely does not represent the text in its entirety. This text has been reconstructed from fragments collected from other Muslim geographers who quoted Tamim in their own writings.25

Most of Tamim’s text comes from quotes in Yaqut al-Hamawi’s “Geography”, written in 1222 in Mosul, as well as from Khurdadhbih, Ibn al-Faqih, Qudama, and others. Yaqut al-Hamawi travelled around Central Asia on the eve of the Mongol conquests, and very likely read the full text of Tamim’s account in the libraries of Merv, Balkh and elsewhere. All of these cities and libraries were later destroyed by the Mongols, and thus the original, complete text is lost.26

There has also been uncertainty among scholars when exactly Tamim travelled to the Uyghurs. Some believe he traveled in the 760’s, but this is unlikely because the Manichean religion had not yet been fully established in Ordubaliq. Additionally, the Kimek Khanate is said to be north of the Uyghurs. This statement only holds true for the 821 when Uyghur power was extended across Zhetisu to the Syr-Darya River, and thus, the Kimeks being located along the Irtysh River in modern day northeastern Kazakhstan were indeed north of the Uyghurs. At any other time, the Kimeks would have been located west of the Uyghur Khaganate.27 More on the Kimeks below.

Some believe Tamim visited the Qocho Uyghurs, the successor state of the Uyghur Khaganate which was established by Uyghur refugees in the 860’s in the Turfan Basin. But this is definitely not true, and can be easily determined by several references in Tamim’s text. These include: the large silk tribute from China, the Khagan being related by marriage to the Chinese emperor, and the Khagan’s golden tent. These pieces of evidence only correlate to the Uyghur Khaganate on the steppes, as later the Uyghur state did not enjoy such commercial and marriage relations with China. Additional evidence disproving this thesis is that, Tamim says it is very cold in the winter and travel then is impossible. In reality, the Turfan Depression is extremely hot in the summer and served only as the winter capital for the Qocho state, while the summer capital was at Beshbaliq north of the Tianshan Mountains, just east of modern Urumqi. If Tamim had traveled to the Qocho Uyghur state it would make no sense for him to say that travel in the winter is impossible. In fact, it might have been preferable. Lastly, Ordubaliq is said to have walls and 12 iron gates, which was later confirmed by archaeological findings.

It is interesting to note that Tamim’s mission was clearly very important as the Uyghur Khagan organized a series of rely horses for him, and he travelled to Ordubaliq with haste, “travelling as hard and as fast as he could.” The fact that the Uyghurs could organize a rely system of horses from the Syr-Darya River across Zhetisu further indicates Tamim’s journey occurred in 821.

Tamim’s exact route is uncertain as the text does not specifically say how he travelled to the Uyghurs and back. All that can be said for certain is that he left from Lower Barskhan (somewhere between Tashkent and Talas) to Ordubaliq, and returned from via Upper Barskhan (highland Kyrgyzstan in the Tianshan Mountains and Lake Issyk Kul). Minorsky notes, that the text mistaken calls the regions of Barskhan “Nushajan”.28 Despite the lack of specifics in the text, we can speculate and make an approximate outline of Tamim’s journey.

First, Tamim likely travelled north through Lower Barskhan, which appears to have been the northern most extremity of Central Asia’s sedentary world.29 From Lower Barskhan the road branches to the left (north) and to the right (east). To the left, the road goes to the Kimeks.

Most of our knowledge on the Kimeks comes from Arab and Persian geographers. The area they nomadized around was centered on the Irtysh River in modern day northeastern Kazakhstan, and they roamed as far as south-central Siberia in the north, the western Altai Mountains in the east, Lake Balkhash in the south, and the Aral Sea in the west. The Kimek tribal union emerged sometime around 766, around the same time the Karluks occupied Zhetisu. Their union was made of up 7 tribes.30 The Kimek’s wealth was largely based on the furs trade. Their proximity to the forests of Siberia and their military power allowed them to dominate the Uralic tribes there, and extract tribute in the form of furs, which were then traded to the Arabs and Tibetans in the south. In the case of the Kimeks, as well as the Khazars, Rus and Vikings, we can speak of a “Fur Road” instead of the Silk Road.31

The Kimeks were able to defeat of Karluks in 840, which led to formation of the Kimek Khaganate. With greater wealth and political power, nomadic camps were remade into walled-towns made from mud-brick.32 In order to feed this urban population, agricultural production was started. Like other Turks of this era, they were initially shamanists who worshipped Tengri as the supreme deity, and later also adopted Manichaeism, Zoroastarism, Buddhism and Islam due to missionary efforts by Sogdians and Arabs.33 The Kimek Khaganate eventually collapsed sometime in the 12th century due to the Qun, who were possibly the Cuman Turks.34 Afterwards, tribes that were before a part of the Kimeks likely joined with the Kipchaks in the west,35 while some went further northeast and mixed with Samoyedic, Caucasoid Yenesi Kyrgyz in the Yenisei River basin.36 At the time of Tamim’s journey, the Kimeks were likely in some degree of subordination to the all-powerful Uyghur Khaganate.37 The text also says Tamim visited the king of the Kimeks. This likely occurred during his return journey.

After Lower Barskhan, Tamim took the road going eastwards along the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains. The steppe region that Tamim says is deserted except for tents is likely the stretch from Lower Barskhan (Talas) to Zhetisu. After this, Tamim would have passed through Zhetisu and Suyab, the old capital of the Western Turks that was later occupied by the Turgesh, Karluks and Uyghurs. Suyab and most other cities and towns in the steppes were not originally built by the nomads themselves, but by the Sogdians, who used them primarily as marketplaces within the steppe world. This route would have eventually led Tamim to either the Ili River Valley or the Zungarian Altau Mountains, both of which constitute the modern day border between Kazakhstan and Xinjiang, China.

Here we encounter the most mysterious segment of Tamim’s journey. In paragraph 1 it says, “he traveled twenty days among villages lying closely together and cultivated tracts(imarat). The people, all of them, or most of them, were Turks”. This statement greatly confused Minorsky in his commentary, and caused him to be unable to exactly determine which route Tamim took on his way to Ordubaliq. This mystery can be resolved by examining the journey of Sallam the Interpreter, from 842 to 844.38

Sallam the Interpreter was dispatched by the Abbasid Caliph al-Wathiq to discover the mythical Alexandrian Wall, built by Alexander the Great during his campaigns in Asia in order to seal of the savage tribes of Gog and Magog away from the civilized world. The tribes of Gog and Magog were thought to be descendants of Japheth, and were often equated with the nomadic people on the northern steppes. Sallam’s quest lead him first to the Daryal Pass in the Caucasus, but unable to located the wall he eventually found his way to the Jade Gate, the entryway to China, at modern Jiayuguan near Dunhuang. During this trip Sallam took a similar route as Tamim across the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains.

After leaving from the Khazars, Sallam traveled west across the endless, barren steppes, to the east of the Pechenegs, and eventually reached a “fetid land” that is said to have an “evil odour.”39 Shortly after passing through this region, Sallam encounters a “black wind.”40 While this information is limited, it can at least be determined this is somewhere in eastern Kazakhstan or in Zungaria (northern Xinjiang), because it is east of the Pechenengs, who at this time nomadized around central Kazakhstan. There are several places in this part of the world that these two descriptions could apply to, but with some confidence we can determine that the “fetid ordour” refers to Lake Alaqol and the “black wind” refers to the Zungarian Gate.

As stated above, Sallam was seeking the location of the Alexandrian Wall, and thus he would have naturally investigated any geographic features that functioned as a gateway for nomads and that could potentially be the location of the gate that sealed Gog and Magog away. He visited Dabancheng Pass and the Jade Gate for exactly this purpose, and thus it only goes to reason that he would also inspect the Zungarian Gate. The Zungarian Gate consists of a valley that cuts through the Zungarian Alatau Mountains, and serves as the main access point between the steppes of Zunagria and the Kazakh steppes. The wind that blows through the Zungarian Gate is notoriously strong, and at the gate’s western end lays the Aalaqol Lake, which is infamous for its reeking ordour.

After passing through this region, Sallam headed towards the Dabancheng Pass, which leads from Zungaria to the Turfan Basin. Between the “black wind” and the Dabancheng Pass, Sallam noted the region was full of “ruined towns”, which according to people he asked, had been destroyed by Gog and Magog. These ruined towns were likely somewhere between the Zungarian Gate and Dabancheng, in the region of Zungaria. This region is mostly arid steppe, except for lands immediately north of the Tianshan Mountains, near modern Shihezi. Similar to Semireche, this land is watered by rivers and streams coming down off the mountains. These ruined towns were likely spread across the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains in Zungaria, from Lake Sayram to Beiting city, near modern Urumqi. These towns were initially Sogdian colonies, and served as marketplaces for local nomads to trade and caravan-sarais for traveling merchants. Beiting city, located near the northern entrance of the Dabancheng Pass, had by the 840’s seen several decades of fighting as the Tibetan-Uyghur conflict became centered on the Beiting-Dabancheng-Turfan region.

Tamim likely either took a similar route as Sallam did two decades later via the Zungarian Gate, or he traveled via the Ili Valley, passing by the town of Almaligh, located near the modern city of Ili, and Lake Sayram. Either way, Tamim then went east towards Ordubaliq, along the route that runs along the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains. The same towns full of Turks that Tamim speaks of are almost certainly the same ruined towns that Sallam speaks of. Tamim’s statement that the inhabitants are mostly Turks refers to the local nomadic population. The towns’ original Sogdian population had likely declined by this point, or had been assimilated with the Turks through mixed-marriages.

Something happened during the intervening three decades, between 821 and 842-844, which destroyed these towns. There are two likely possibilities. Either the Uyghur-Karluk war continued, with the towns lying between them being destroyed in the process of the fighting, or the Uyghur Khaganate’s other enemy, the Tibetans, raided these towns from the south during the period they controlled the Tarim Basin. In fact, this is probably the more likely cause, as the Tibetans and Uyghurs during this period were locked in warfare over the eastern Tianshan Mountains. Additionally, in 816 the Tibetan cavalry rode within three days of the Ordubaliq on raid. There is good reason to speculate that Tibetan cavalry could have easily raided the settled communities north of the Tianshan Mountains by crossing over passes such as the Muzart, or following a similar route as the G216 and G217 highways which cross over the central Tianshan Mountains north to south.

Tamim likely headed east on a largely straight line, continuing along the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains. Little else is said here, but Tamim likely passed through Beiting and Barkol before entering on to the Mongolian Plateau and reaching the Uyghur Khagan at his capital of Ordubaliq.

The text refers to the Uyghurs as the “Toquzghuz”, a term which has potential to cause confusion and should be explained. The word Toguzoghuz means “nine tribes”, and refers the larger tribal grouping that the Uyghur Turks were a part of. With the Toquzoghuz, the Uyghurs were merely one tribe among eight others. The Uyghur tribe itself consisted of ten clans, headed by the Yaghlaqar clan. Turkic states of this era were usually organized in the following manner: a royal tribe, inner tribes, and other tribes. The inner tribes were close followers of the royal tribe, had helped found the state and supplied the high officials and generals. The outer tribes were largely those who were absorbed into the khaganate at a later date. The Yaghlaqars served at the royal tribe, supplying the Khaganate’s monarchy, why the larger Toquzoghuz grouping made up the inner tribes, and were effectively the nucleus of the state. Contemporary Muslim writers almost always referred to the Uyghurs and their Khaganate as the “Toquzoghuz.”41 Elsewhere in the text, Tamim mentions the Khagan as having seventeen chieftains. These were likely the highly high officials and generals that were drawn from the broader Toquzoghuz-inner tribal grouping.

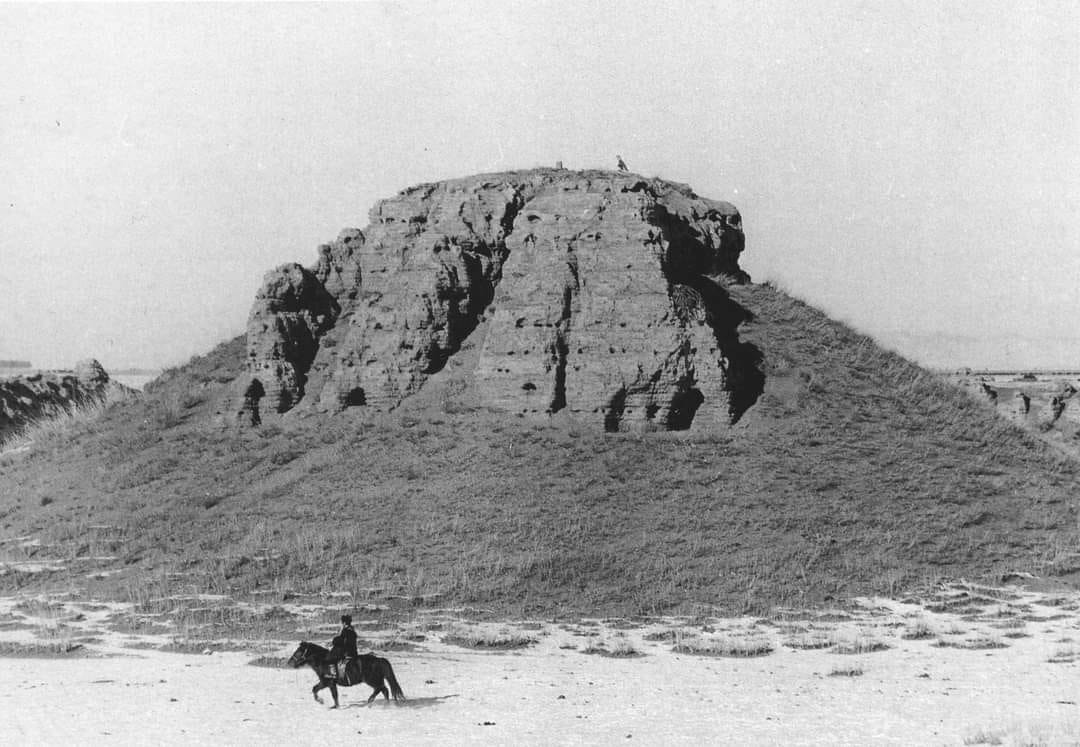

What Tamim says about Ordubaliq is maybe the most noteworthy information in the text. He says “this is a great town, rich in agriculture and surrounded by rustaqs full of cultivation and villages lying close together”, “The town has twelve iron gates of huge size” and “The town is populous and thickly crowded and has markets and various trades.” The significance is these statements are that Tamim indicates Ordubaliq is not a mere nomadic camp, or even a haphazardly constructed city consisting of assembled nomadic tents, but an actual city. Ordubaliq was large enough to justify twelve separate gates, and hosted a large enough urban population that extensive agriculture was required. Everything that Tamim says here has been proved true thanks to archeological findings. The ruins of Ordubaliq, located in the Orkhon River valley, have twelve gates along its walls, which cover an area of 33km2. This is comparable to the size of the Tang capital of Chang’an, which prior to the An Lushan Rebellion, was the largest the city in the world. Additionally, archaeological evidence of farming for the 9th century has been found nearby.

Tamim’s reference to the Uyghur Khagan’s golden tent on top of his palace is also confirmed in Tang Chinese sources. The Tang Shu even records the Krygyz Khagan, who would later bring about the downfall of the Uyghur Khaganate, saying, “Your luck has run out! I will take your golden tent, and in front of your tent I will race my horse and plant my flag.”42 The symbolism of the ruler’s golden tent is an ancient motif among the steppe nomads of Eurasia. The Scythians kings lived in large golden tents, and this custom and symbolism was transferred to the Medes and Persians due to Scythian expansion into the Near East in the 7th century BC.43 The extent of this custom among both the ancient, Iranic, Indo-European/Aryan Scythians and the Altaic Turkic Uyghurs raises very important questions on the exact origins of the Turks.

It has long been speculated that a significant Scythian and/or other Indo-European elements were present among the ancient Turks. Archeological findings similar to Scythian cultural artifacts have been found as far east as Ordos in China and Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, Russia. There is also documentary evidence of Indo-European groups such as the Yuezhi living as far east as modern day Gansu province in China, and some speculate that there was an Indo-European contingent within the State of Qin which unified China in the 2nd century BC and created the first Chinese empire. The Uyghurs were known to have been largely Asiatic appearance, but nevertheless we can speculate that the genealogy of this symbol can be traced back to the Scythians.

Tamim also speaks briefly on the economic-political relationship between the Uyghurs and Tang China. Tamim visited the Chongde Khagan shortly after his marriage to the Taihe Princess, daughter of the Tang Emperor Xianzong (reigned 805-820). The Chongde Khagan would die in 824, and the Taihe princess would later go on to play an important role in the aftermath of the Khaganate’s collapse. She was eventually safely returned to China in spring of 843.44 The marriage of a Chinese imperial princess to the ruler of a non-Chinese people was very important. The marriage to an imperial princess brought immense prestige to the husband and ruler, as China was effectively the cultural, political and economic center of eastern Eurasia. This prestige would translate into greater authority and respect for the husband of the princess among all the other tribes outside of China. In other words, this would be the equivalent of marrying the daughter of the Roman Emperor, or to be personally honored by the American president and congress in some very meaningful way. The marriage would also result in a very large dowry given to the husband, which could in turn be distributed to his followers in order to further consolidate his rule.

Tamim also mentions the economic relationship between the Uyghur Khaganate and Tang China. As mentioned above, the Uyghurs negotiated highly favorable terms of trade with the Tang imperial court in exchange for their assistance in suppressing the An Lushan rebellion. Annually, the Uyghurs would export 7500 horses to China, and in exchange, they received 40 pieces of silk per horse. This resulted in the Uyghurs receiving an average of of 300,000 pieces of silk in revenue a year from Tang China. This was far more silk than what the Uyghurs required, and all excess silk was sold westwards. This had the effect of greatly stimulating Silk Road trade, and turning the Uyghur Khaganate into one of the most important trade emporiums in Eurasia. Tamim’s figure of 500,000 pieces of silk, 200,000 pieces more than usual, can be explained as either being due to the marriage dowry that the Tang gave to the Khagan, or simply a mistake and exaggeration. Ancient and medieval authors regularly gave false and exaggerated figures for the size of armies and other such things.

Tamim likely returned by following the same route he took to Ordubaliq. The only difference is that he seems to have travelled through “Upper Barskhan.” This region is without a doubt Lake Issyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan and the surrounding mountainous region.45 He describes the lake as being large, hosting a large population, as being a “square-shaped pond and around it are high mountains”, and there being ruins nearby. All of these statements indicate Issyk Kul, which is located in the Tianshan Mountains, is known to have ancient ruined towns both along its shoreline near modern Karakol and other ruins sunken underwater. While not exactly square-shaped, it is shaped as an oval of sorts.

What is most interesting here, is that Tamim indicates that the Upper Barskhan region served as a refuge of steppe tribes who had fled off the steppes due to pressure from more powerful invaders. We can speculate that the population of Upper Barskhan was likely a mix of Turkic speakers who had fled there following the collapse of the Western Turkic Khaganate and the Turgesh collapse, as well as an even older layer of Indo-European peoples, such as remnants of the Yuezhi and others. The most inhabitants of this region, the Kyrgyz, are known to have a significant Caucasian genetic admixture. It is also known there were Sogdian colonies throughout the western Tianshan Mountains as well. The Karluks’ inability to subdue the Upper Barskhan is also interesting, and likely a result of the region’s mountainous and forested terrain, which largely negates the advantages in mobility that nomads enjoy on the open steppes.

A significant inconsistency is apparent in paragraph 13, where Tamim appears to mix up the 821 Uyghur invasion of Central Asia with the Battle of Talas in 751. We know for certain that what he is actually referring to here is the Talas battle because he mentions China, and that soldiers captured at this battle introduced paper making technology to the Islamic world, something that is well established to have been a consequence of the Battle of Talas.

The reference to pebbles in Turkic shamanism is also very interesting. I do not know or have much to say on this, other than that the religion of the ancient Turks is a topic that deserves further investigation.

In the grand scheme of things, Tamim’s mission to the Uyghur Khaganate was likely of little importance. Uyghur power which had been extended west into Zhetisu was not maintained, and instead the Uyghurs withdrew back to Zungaria and the Karluks were able to reestablish themselves in the region. In 822 the Uyghurs and Tibetan made peace, and this was followed by Tibet making peace with Tang China in 823. What had been a “world war” of sorts in eastern Eurasia beginning in the early 8th century between Tang China, the Turks, Arabs and Tibetans, had largely come to an end. While Tamim’s journey likely had little importance at the time, his account as a historical document is immensely important. Ironically, his journey serves our benefit far more than it served his contemporaries.

And one last note, for readers who enjoyed this, I strongly recommend “Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North” and “Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam's Quest for Alexander's Wall.”

Bibliography

Beckwith, Christopher I. The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press, 1993.

Beckwith, Christopher I. The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China. Princeton University Press, 2023.

Drompp, Michael Robert. Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Brill, 2021.

Drompp, Michael Robert. “From Qatun to Refugee: The Taihe Princess among the Uighurs.” 2007.

Drompp, Michael Robert. “The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest.” 2002.

Golden, Peter B. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, 1992

J., V. D. E., & Schmidt, A. (2014). Gog and Magog in early Eastern Christian and Islamic sources sallam’s quest for Alexander’s wall. BRILL.

Kovalev, R. K., & Mako, G. (2016). Kimek Khaganate. The Encyclopedia of Empire, 1–2.

Mackerras, Colin. The Uighur Empire According to the T’ang Dynastic Histories: A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations 744-840. Colin Mackerras, Editor and Translator, 1972.

Minorsky, Vladimir. “Tamīm Ibn Baḥr’s Journey to the Uyghurs.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 12, no. 2 (1948): 275–305.

Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

UNESCO. History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Volume IV The Age off Achievement: A.D. 750 To the End of the Fifteenth Century : ( Part One ) The Historical, Social and Economic Setting, 1998.

See Oswald Spengler’s “Decline of the West”

The most famous of these sites in Tuva is Por-Bazhyn. The Uyghurs also built numerous other fortresses in the region, in defense against the Yenisei Kyrgyz to the north. Most of the research on these sites is only in Russian

Chinese sources on the Uyghurs were compiled by Colin Mackerras, in his book “The Uighur Empire according to the Tʻang Dynastic Histories. A study in Sino-Uighur relations 744-840”

Svat Soucek, “A History of Inner Asia”, 77.

UNESCO, “History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Volume IV”, 91.

Svat, “A History of Inner Asia”, 76.

The names “Zhetisu” and “Semireche” both mean “Seven Rivers” in Turkic and Russian, respectively

Christopher Beckwith “The Tibetan Empire in Central Eurasia”, 165.

Zoroastrianism

Manichaeism

Ordubaliq

China

Old Persian unit of measurement, equivalent to 5 kilometers

The Kimek were a Turkic tribal confederacy located in modern day northern and northeast Kazakhstan

The Uyghur Khagan Chongde had married the Tiahe Princess earlier that year, daughter of Emperor Xianzong, reigned from 805 to 820

Kyrgyzstan and the Tianshan Mountains

Karluk, a Turkic tribal grouping

Lake Issyk Kul in modern Kyrgyzstan

Kuvekat

Bahr writes mistaken here. The Uyghurs did not attack China, but instead invaded Central Asia. See my explanation in commentary section below

Surushana was a Sogdian region that is known to historians as either Osrushana, Usrusana, or Ustrushana. It correlated to modern day Istaravshan, Tajikistan

Spelled in English as Samarkand today, in modern day Uzbekistan

This is a reference to the battle of Talas between the Arabs and China, in 751. Tamim just has the dates confused

V. Minorsky. “Tamīm Ibn Baḥr’s Journey to the Uyghurs”, 277.

Ibid., 276-277.

Ibid.

Ibid., 302-303.

Ibid., 290.

Ibid.

Kovalev & Mako. “Kimek Khaganate”, 1.

Peter Golden, “An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples”, 204.

Kovalev & Mako. “Kimek Khaganate”, 2.

Golden, “An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples”, 205.

Ibid., 276.

Ibid., 210.

Ibid., 186.

Ibid., 202.

See “Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam's Quest for Alexander's Wall”

Ibid., 218.

Ibid., 219.

Minorsky, 287.

Drompp, Michael Robert. “The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest”, 3.

Beckwith, “The Scythian Empire”, 99-100.

See Drompp, “Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History.”

Minorsky, 290.

The amount of work you put into these writings is incredible. I never in all my life thought I would be interested in Eurasia but you've changed that in me. You deserve many more views and subscriptions than you have, and I plan on becoming a paid subscriber after I get married this summer.

This was fascinating! Thank you for writing. especially appreciate the intro which was v helpful for readers like me who don’t know about this region / history