The Bukharan Jews at Dushanbe - Dmitri Logofet, 1913

Translation about the Bukharan Jews of Dushanbe in Mountainous Bukhara

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation about the Bukharan Jews of Dushanbe (then known as Dushambe), which was then a small trading town in Mountainous Bukhara and today is the capital of Tajikistan. The Bukharan Jews are a subgroup of Mizrahi Jews based in Central Asia, and named such by the Russians because they largely lived within the territory of the Bukharan Emirate.

The author, Dmitri Nikolaevich Logofet, was born in 1865 near Oryol, south of Moscow. After cadet school he studied Eastern languages with the Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and later served with the Border Guards in Central Asia. This translation is an excerpt from Logofet’s book “In the Mountains and Plains of Bukhara.” The original text can be found here. The source for this translation can be found here.

A few additional notes. “Mountainous Bukhara” largely refers to the eastern territory of the Emirate of Bukhara in the Hissar and Pamir Mountains, which today largely constitutes the country of Tajikistan. Following the Bukhara’s defeat by Russian forces in the 1860’s, Bukhara became a protectorate of the Russian Empire.

The Jewish diaspora in Central Asia is very ancient, dating back to time of the Babylonian Exile. Since then, an Jewish diaspora has existed across Central Asia and the Silk Road, including numerous historical Jewish settlements in China itself. Interestingly, Jewish letters from the 8th century have been discovered at Khotan, in the Tarim Basin, which at the time was a great Buddhist city trapped between the warring Tibetan and Tang empires. These Jewish commercial networks also extended in Europe, resulting in the Khazar conversion to Judaism in the 8th century. For more on the Jews and the Silk Road, I would recommend the books “Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization” by Richard Foltz and “Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travelers in the Far North.”

Lastly, a large collection of old photographs of Bukharan Jews can be found here.

In the Mountains and Plains of Bukhara: The City of Dushanbe

The city of Dushambe (Monday) is located not far from the confluence of the rivers Zigdi-Darya, also known as Dushambe-Darya, and Kafernigan, with the former flowing into the latter four verstas1 below the kishlak2 of Munka-Tyube. As it is one of the main commercial centers for grain, Dushambe attracts a mass of traders to its bazar, who mainly transport grain from here to Bukhara.

The population is almost entirely Tajik, among whom Uzbeks and Kyrgyz are only rarely encountered. Further beyond here Uzbeks begin to predominate, mainly those from the Kungrad tribe, and Kyrgyz of the Kchi-mark-yuz and Lokai tribes who bread Kyrgyz horses of the so-called Lokai breed. These horses are partially Hissar horses by blood, which were improved by breeding them with Arabian stallions. One quickly notices the number of strong and quite tall horses found in the bazar, which share little resemblance to the mountain horses of eastern Bukhara.

The Uzbeks also predominate, and only rarely are Tajiks encountered.

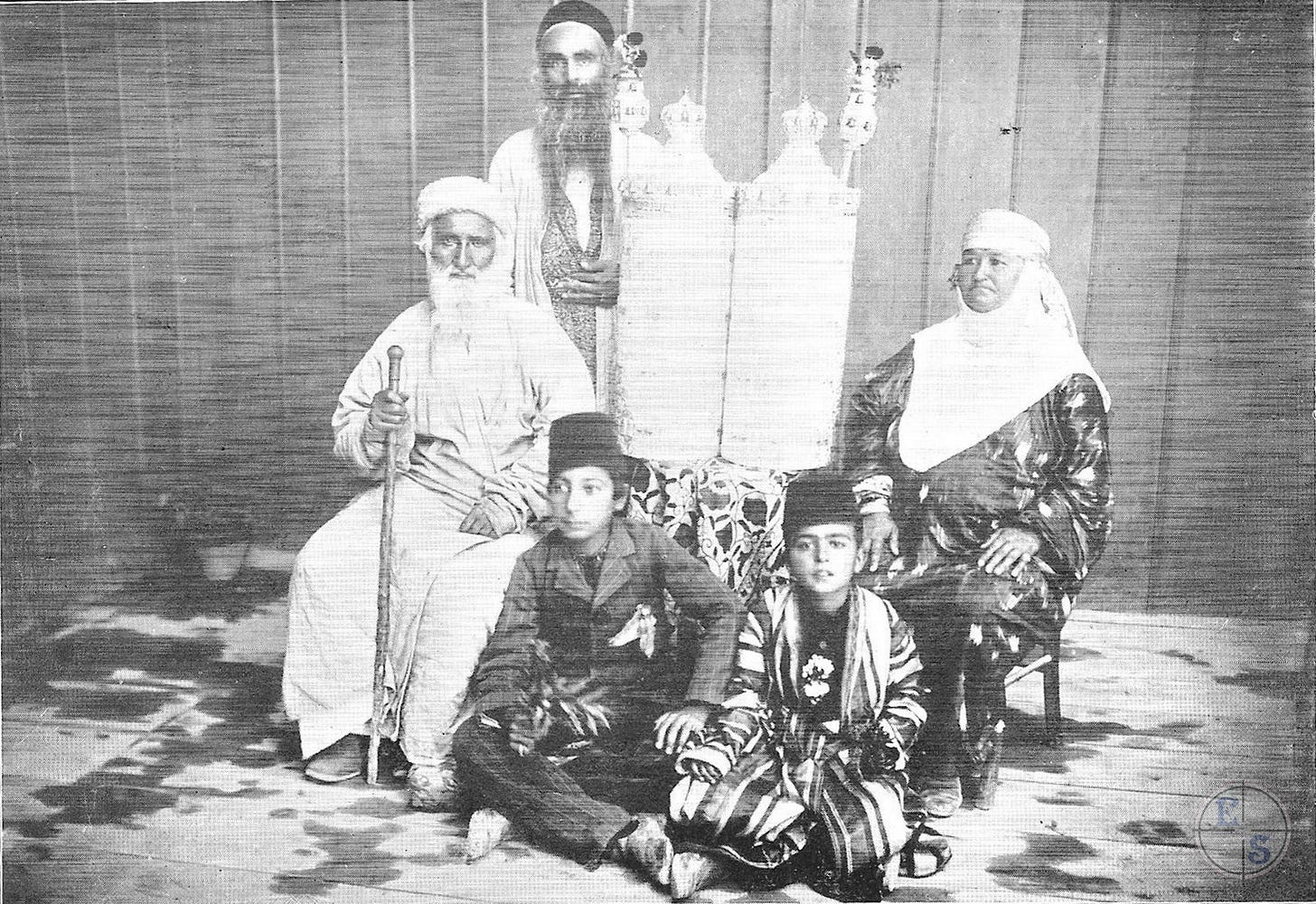

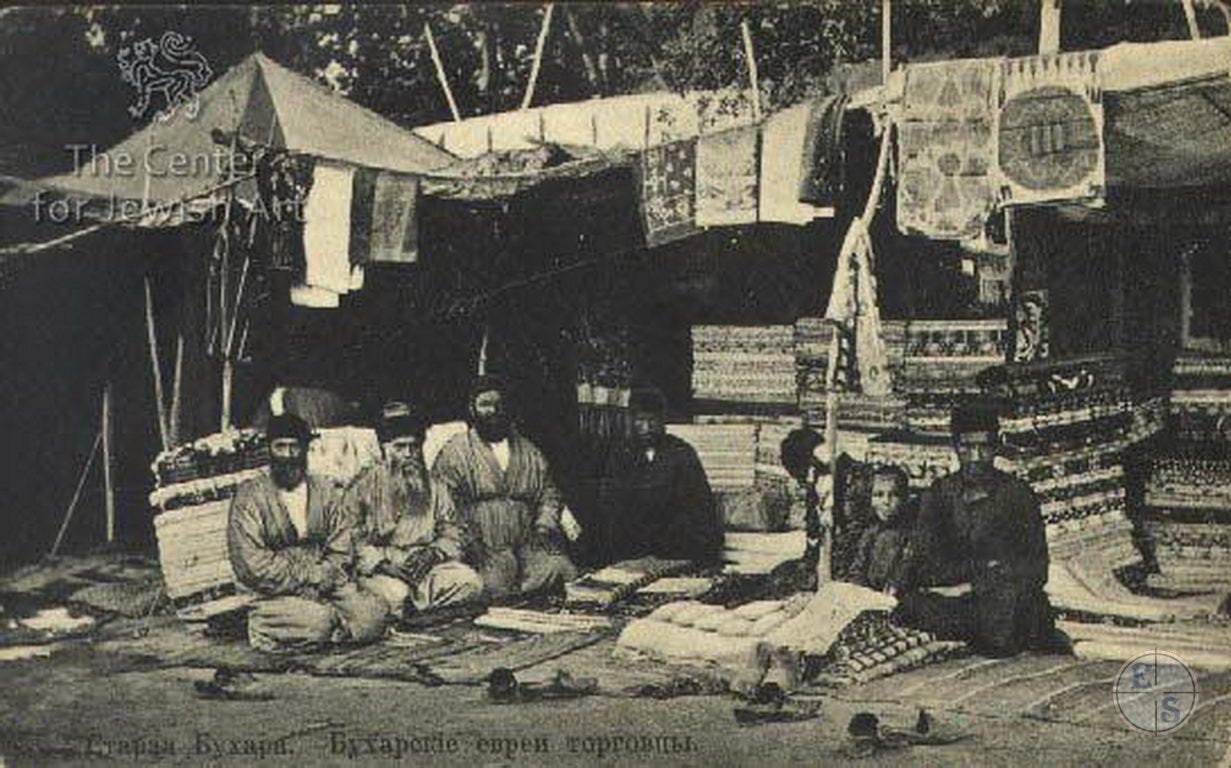

Having long been a trading point between eastern and western Bukhara, Dushambe has become a place where a significant number of Bukharan Jews have settled, who have seized control of nearly all the local trade. Their beautiful faces remind one of Biblical paintings.

Having preserved their type, religion and language, the Bukharan Jews are completely different from the Jews in the Kingdom of Poland, with which they have almost nothing in common. Having already settled in the city of Bukhara prior to its conquest by the Arabs, they formed their own particular group of people, which, despite tribal kinship with the conquerors, occupied a very difficult position among the Muslims. Their inherent proclivity towards commerce meant that all of the trade in the Bukharan state fell into their hands, and thanks to this, a very large very sum of wealth was quickly concentrated in their hands. The high level of prosperity enjoyed by the Jews compared to the rest of the of the population and the indebtedness of the many Muslims to them led to the seizures and plundering of Jewish property in very distant times.

The general lack of rights for Bukhara’s subjects contributed to this. Bukhara’s rulers were forced to turn to loans in order to fund their wars and way of life, and instead of paying their debts, they instead sequestered property from the Bukhara’s Jews. Their firmness in matters of religion and isolation from Muslims created hostility towards them from among the Muslim clergy, who declared them to be mekrukh, in other words, vile and unclean. The Bukharan government took advantage of this and went even further, creating an entire series of restrictive laws against the entire Jewish population. Marriages between Muslims and Jews were forbidden, they were banned from bearing arms, and together with this they were banned from joining the military or from gaining appointments with the state, law makers introduced external distinguishing signs that would make Jews easily recognizable and to ensure that they would not be mistaken for being Muslims. They were banned from horse ridding, and instead of wearing a belt they had to wear a rope, and upon meeting a Muslim any Jew riding a donkey had to get off and bow (Kulduk).

Thus, the lack of rights forced the Jews into a secluded life, but despite this, the Jews of Bukhara little in common with their Russian relatives, who in general have many sympathetic qualities, which they inherited from the patriarchal ways of their distant ancestors who lived in Palestine.

Impeccable honestly, truthfulness in word, and the lack of any fraudulent method in commercial affairs, they soon won respect from the Russian merchants who traded with them. Having a leading place in the Russian-Bukharan trade thanks to their enterprising spirit, since the very beginning of their relations with Russia, Bukharan Jews have occupied the role as intermediaries. They established wholesale warehouses full of goods from Russian merchants and then supplied nearly all of the Muslim cities in Bukharan Khanate with these goods, and at the same time concentrating in their hands the entirety of trade of raw silk and its processing into yarn. Nearly all silk dyeing workshops and the production of silk materials belongs to Jews, who have developed their own particular methods and ways in this industry. And at the same time, Russian manufacturing and household goods are also going from factories to their hands.

“You can get vodka here, if you like,” reported a Cossack prior to breakfast, who had already managed to find some at the bazar.

“Where did the vodka come from?” I asked in surprise.

“There is a factory here, the Bukharan Jews make their own vodka, it is as strong as our spirits. They are making it out of fruit, your highness. Very fragrant,” he added, entering the room and, as if in confirmation, brought with him a strong fusel small, which indicated to us that the scout had already had quite a bit of the fruity spirit that he so liked.

“Is it allowed to produce vodka in a Muslim city?” B. asked the Amlyakdar.3

“Ah, tyura, this is our misfortune, although the emir allowed the Jews to make vodka for themselves and forbid its sale to the faithful, temptation is great, and many, unable to withstand temptation, often drink by themselves secretly.

The yellowish colour of vodka that was served turned out to be pure spirit, but frightfully strength, with a strong fusel smell and a distant similarity with bad cognac.

Old unit of Russian measurement. 1 versta equals 1.06 kilometers or 3,500 feet.

A Turkic word meaning “winter quarters.” Villages in Central Asia are often called kishlaks.

The amlyakdar was the local Bukhara official who collected taxes and information on behalf of the emir. He was subordinate to the Bek, who was the local governor on behalf of the emir.