The Creation of the Russian Imperial Frontier Guard in the Trans-Caspian Oblast and Mountainous Bukhara - Vladmal, Pogranec.ru, 2008

Translation on the creation of Russia's Imperial Frontier Guard in Central Asia, from the Caspian Sea to the Pamir Mountains

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of a lengthy and very well researched forum post detailing the creation of the Russian Empire’s frontier in Central Asia. The focus of this forum post is the establishment and implementation of border guards and customs inspection from the Caspian Sea to the Pamir Mountains in the 1890’s. This translation is a follow up to my post from earlier this year about the Big Cats of Kopet Dag Mountains. I discovered this post while searching on Yandex for the Chakan-Kala post, one of the many outposts Russia created in modern Turkmenistan to guard to the border with Persia. The source for this translation can be found here, on the forum Погранец.ру, a forum dedicated to Russia’s Frontier Service, a state organ subordinate to the FSB and tasked with guarding Russia’s international borders. From what I can tell, all forum members have served in the Frontier Service in the past. The forum’s extensive photo gallery can be found here. During the Russian Empire, the organ tasked with securing the border was called the Separate Border Guard Corps (OKPS), and was subordinate the Ministry of Finance, as customs inspection, taxing imports and countering contraband were some of its primary responsibilities.

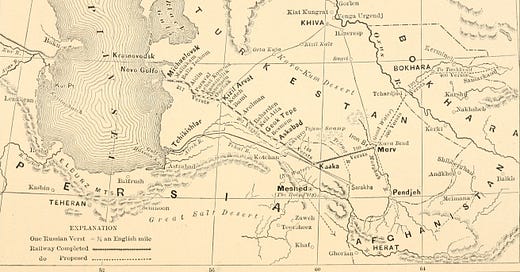

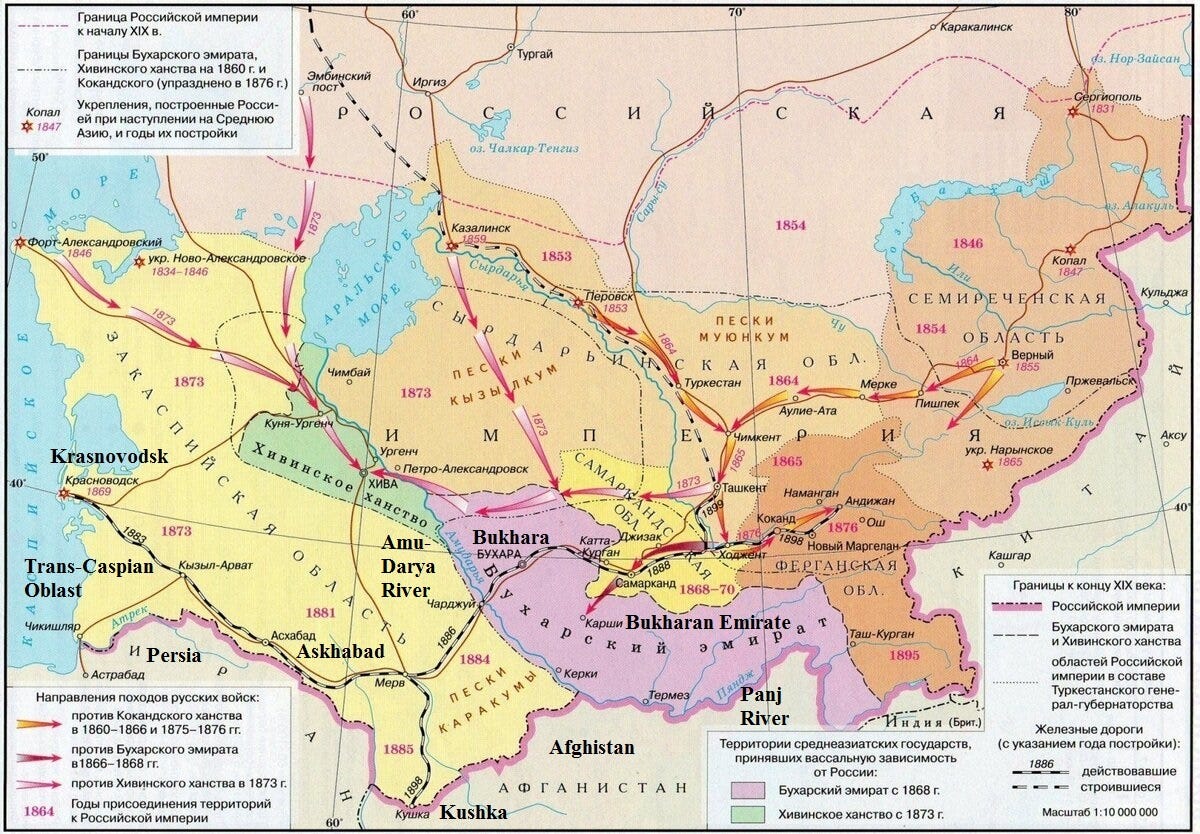

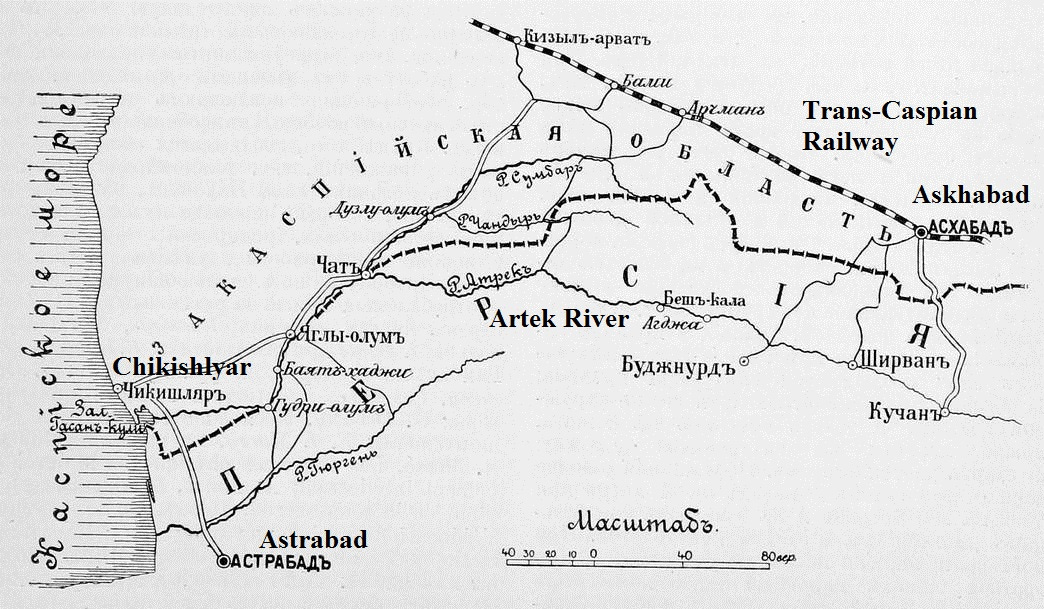

The territory from eastern shore of the Caspian Sea to the Pamir Mountains represented one of the Russian Empire’s most distant and alien frontiers, as well as being one of its most difficult to guard due to its remoteness and the porous nature of the local geography. The region consisted of two general territorial units. In the west, east of the Caspian Sea, was the Trans-Caspian Oblast, a territory conquered in the 1880’s which largely consisted of deserts and oasises inhabited by the particularly fierce Turkmen nomads. To it’s south were the Kopet Dag Mountains which separate Trans-Caspia from Persia. The second was “mountainous Bukhara”, the territory of the Bukharan Emirate located in the Pamir Mountains. In 1860’s Bukhara was militarily defeated by Russia, who subsequently made Bukhara a vassal state with its foreign policy and borders controlled by the Russian imperial state. Mountainous Bukhara spanned the right side of the Amu-Darya River, known as the Panj in its upper reaches. On the left side of the Panj and Amu-Darya lays Afghanistan. The Trans-Caspian Oblast largely correlates to modern day Turkmenistan, while the city of Bukhara itself is in modern Uzbekistan and “mountainous Bukhara” largely equates to Tajikistan. These territories bordered Persia and Afghanistan to south. The borders set by the Russian Empire remained unchanged throughout the Soviet and post-Soviet periods.

There are few noteworthy things here that deserve to be highlighted. First, the initial recruitment of locals is very interesting. While their questionable loyalty would be a concern, they would have specialized knowledge of the local landscape, people, and routes for trade and contraband. Such jobs would have also provided good employment and status to locals, which would have helped the Russian state ingratiate itself with them. If I remember correctly, I remember reading that at Kosh-Agach, a small plateau region south of the high Altai Mountains on the Mongolian frontier, the FSB Frontier Service represents the single largest employer in the region. The figure of Mikhail Georgievich Baev, a native of Ossetia in the Caucasus, is also interesting. It shows that non-Russians were not only well integrated into the imperial state, they also helped Petersburg integrate additional territories. Caucasians in general played a very large role in conquering the territories of Central Asia on the eastern Caspian shore, namely Khiva and Trans-Caspia. Having traveled across some of Russia’s international land borders, I can attest to the large number of non-Russian personnel employed by the Frontier Service today. Based on what I saw, I would say that for at least the border crossings that I transited through, the majority of personnel are not ethic Russians.

It should be pointed out while modern day Russia no longer directly controls Central Asia, it still views its effective borders as being those of the USSR. Dmitri Medvedev earlier this year said that Russia’s strategic borders lie in the Pamir mountains. This is not a statement of territorial pretensions, but an acknowledgement of Russia’s practical reality. While the five Central Asian former Soviet republics are all independent states, they still maintain extensive ties to Moscow, primarily in travel, trade and labour migration. Russia maintains a visa-regime will all ex-USSR Central Asian republic minus Turkmenistan. Vast numbers of Central Asian temporary foreign workers go to Russia every year, from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in particular. Thus while de jure sovereign, from Moscow’s standpoint these countries are still very much within Russia’s sphere, which makes Central Asia’s border with Afghanistan also Russia’s effective, actual border in the region.

A few notes on translation. I translated the word pogranichny (пограничний) as frontier while word granitsa (граница) I translated simply as border. This is an important distinction. In Russia the modern day Frontier Service controls and monitors not merely the border itself, but the territory immediately adjacent to the border as well, and special permission is required to visit regions that are within this border zone. If I am not mistake, the entirely of Ingushetia’s territory that is located in the mountains (primarily the Assa Valley) is considered a frontier zone and requires special permission to visit. This special permission entails a “propiska” from the local FSB office.

For a great book on how Russia’s borders changed over time, I would recommend “Beyond the Steppe Frontier” by Soeren Urbansky, which examines the Russian and Soviet border with China in the Trans-Baikal region and how it began as a porous, loosely defined zone guarded by Cossasks to being a tightly controlled frontier, guarded by extensive fortifications under Stalin, as a reaction to security threats emanating out of Manchuria.

Also worth noting that the term distantsiya, not to be confused with the English word distance, was an administrative unit that was used by the Russian Empire in the 19th century primarily in the Caucasus and Central Asia. I note this in a footnote but thought it should mentioned here as well for clarification.

Establishing Frontier Surveillance1 in the Trans-Caspian Oblast, Middle Asia and on the Right Bank of the River Panj and the Amu-Darya. Part 1.

By the end of the 19th century practically all of the Middle Asian Khanates (Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand) were joined to Russia. The last part of Middle Asia to join Russia was the voluntary submission of the Turkmen tribes of the dead oases of Merv and Pende.

The newly acquired borders with Persia and Afghanistan were initially covered by regular forces and Cossacks, who mainly pursued their assigned military tasks. Countering contraband trade in the frontier regions and the struggle against gangs of robbers was not carried out effectively. Not only was the locality not well studied, customs and frontier supervision were entirely absent.

The situation on the southern border could not remain without attention by the leadership of the country, especially as the position of England, who had its own interests in Middle Asia, was directed to the weakening of Russia’s influence in the region.

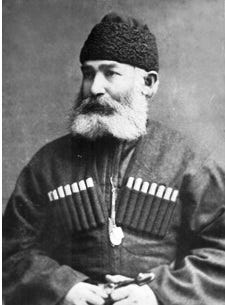

After consideration by on the State Council on the question of establishing frontier surveillance in Middle Asia, Emperor Alexander III on 4th June, 1893 accepted the decision to send a group of officers from the border guard and customs departments to the frontier regions for the purpose of researching the external frontiers of the Trans-Caspian Oblast and of Bukhara. This group was headed by the commander of the Bessarabian customs district Major-General of the General Staff M. G. Baev and was tasked with studying the national particularities and local conditions, which would be necessary for the establishment of customs surveillance there, as in agreement with local authorities.

Mikhail Georgievich Baev, native of Ossetia,2 received a quality military education, graduating from the Konstantin Military School and the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff. He began service with the frontier guards in 1872. He commanded the Taurogen3 brigade of the frontier force. For more than two years he ran the Jurbarkas4 customs district. He then served as an official of special assignments at the Ministry of Finance for overseeing quarantine and customs affairs in the Caucasus. In 1888 he was appointed commander of the Bessarabian customs district, where he worked prior his transfer to Middle Asia.

While touring the Bukharan border on 12th September, 1893, he became very ill. The reconnaissance group connected to this work was suspended.

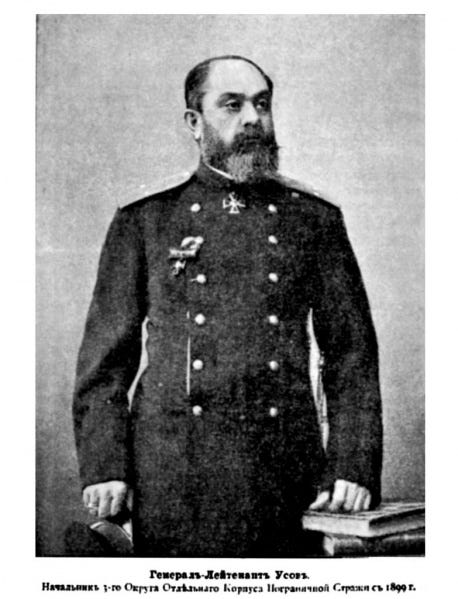

Instead, on 20th September, the commander of the Kalisz5 customs district Major-General Nikolai Antonovich Usov, who had a large amount of practical experience in frontier service, was sent. Upon arriving to Bukhara in September 1893, he studied the materials that had been collected before him by General Baev and headed the commission on research of the external borders of the Trans-Caspian Oblast and Bukhara. Based on the information he received he complied a detailed description of the borders of the Bukharan realm, and also the borders with Persia and Afghanistan. Having assessed the size and character of the movement of trade, directions of main caravan routes, local terrain and climatic conditions in the Bukharan Khanate and the Trans-Caspian Oblast, he prepared a proposal for the creation of customs and frontier surveillance and how they would be implemented there, which in the beginning of 1894 was presented to the Minister of Finance. The commander of the Trans-Caspian Oblast, Lieutenant-General A. H. Kuropatkin and the Emir of Bukhara were both familiarized with the workings of the project, with both of whom approving.

In connection with the unique topography, ethnographic and commercial conditions the Trans-Caspian Oblast and in Bukhara, as detailed by Major-General Usov (detailed here: M. Chernushevich. Service in Peacetime. Part 1, Issue 4, St.Pb.,1906), the continuous guarding of the border in this place, as in the way done along European and Trans-Caucasian6 borders, was deemed to be not expedient, and in some places simply impossible. Therefore, initially is was thought that only frontier post stations would be set up at the most important, already existing commercial points and at every main crossing over the rivers Amu-Darya and Panj.

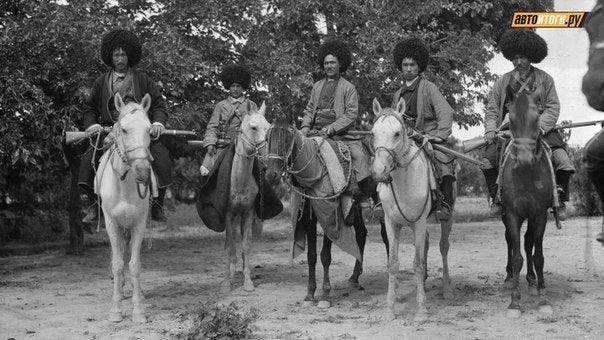

The staffing of these posts with only Russian military personnel was considered unfeasible, the reason being that the lower ranking officials did not know the local language, nor the morals and customs of the local population, as well as the local particularities. The frontier posts were staffed by 8 to 18 people (with their being 13 people on average). It was planned that the personnel would consist of hired dzhigits7 (from among the local population), subordinated to the post stations and under the command of lower ranking officers from the Separate Frontier Guard Corps (will be referred to simply as the OKPS henceforth).

The dzhigits were drawn to the service of frontier surveillance as it gave them greater status. It was proposed that local militia officials would be given uniforms, in addition to shoulder markings that distinguished them the lower ranks of the frontier guards who wore a light-green cloth uniform. Thus, at every post the guards were to have 3 lower ranking officials of the OKPS, one of whom was appointed to a senior post, two others who would be his assistant and 6-15 locally hired dzhigits.

The plan was to form 55 frontier posts consisting of 165 military personnel from the lower ranks of the frontier guards and 546 dzhigits. In the Trans-Caspian customs district – 30 posts, 90 lower ranking officials and 297 dzhigits and in the Turkestan customs district – 25 post, 75 lower ranking officials and 249 dzhigits.

The project provided for the organization of frontier and custom surveillance in two customs district separated by a distantsiya.8 A total of 9 distantsiyas were planned, 5 within the Trans-Caspian Oblast and 4 within the Khanate of Bukhara. It was proposed that the naming of the distantsiyas would be based on the name of the population center at which the commander of the distantsiya would be located at. General leadership of frontier surveillance at every part of the district was entrusted to the field officer, but command of the distantsiyas was given to ober-officers with the rights of commanders of frontier guards:

A) Distantsiyas of the Trans-Caspian District:

1st – initially Kyzyl-Arvatskaya (at Kyzyl-Arvat), then later Krasnovodsk (in Krasnovodsk) with 4 posts:

1) Kazadchiksky – 11 people

2) Kyzk-Arvatsky – 13 people

3) Bakhardensky – 11 people

4) Chakan-Kaleisky – 10 people

2nd – Akhaltekinskaya (in Ashkhabad) with 8 posts:

5) Ashkhabadsky – 18 people

6) Dainesky – 11 people

7) Sulukliisky – 11 people

8) Germabsky – 13 people

9) Firuzinsky – 11 people

10) Gaudansky – 13 people

11) Keltechinarsky – 13 people

12) Graursky – 13 people

3rd – Atekskaya (at Kaakkha) with 7 posts:

13) Babadurmazsky – 13 people

14) Artysky – 13 people

15) Kozgan-Koliisky – 13 people

16) Kaakkhinsky – 15 people

17) Dushaky – 13 people

18) Meanasky – 13 people

19) Chaachsky – 13 people

4th – Serakhskaya (at Serakh) with 6 posts:

20) Rukhnabadsky – 14 people

21) Dovlat-Abatsky – 13 people

22) Serakhsky – 15 people

23) Novruz-Abadsky – 13 people

24) Dana-Germabsky – 13 people

25) Akrabadsky – 13 people

5th - Pendinskaya (at Takhta-Bazar) with 4 posts:

26) Kushkinsky – 12 people

27) Tash-Keprinsky – 13 people

28) Takhta-Bazarsky – 13 people

29) Uch-Adzhisky (on the railway line between Merv and Chardzhui9) – 13 people

B) Distantsiyas of the Turkestan customs district:

1st – Kerkinskaya (in the city of Kerki) with 7 posts:

1) Polvartsky – 13 people

2) Kerkinsky – 15 people

3) Khabatsky – 10 people

4) Bossaginsky – 11 people

5) Dogano-Khodzhansky – 9 people

6) Khodzha-Salarsky – 11 people

7) Kelifsky – 15 people

2nd – Patta-Kisarskaya (at the village of Patta-Kisar) with 8 posts:

8) Kara-Kamarsky – 9 people

9) Chushka-Guzarsky – 18 people

10) Shurabsky – 9 people

11) Patta-Kisarsky – 18 people

12) Airatonsky – 9 people

13) Khatyn-Rabatsky – 13 people

14) Aivadsky – 13 people

15) Takhta-Kuvatsky – 11 people

3rd – Saraiskaya (in the village of Sarai) with 6 posts:

16) Karakul-Tyubinsky – 13 people

17) Saraisky – 13 people

18) Kakulsky – 13 people

19) Sayatsky – 13 people

20) Chubeksky – 13 people

21) Bogoroksky – 13 people

22) Kala-i-Khulebsky – 18 people

23) Tabi-Dorinsky – 13 people

24) Garmsky – 18 people

25) Dumbarachinsky – 13 people

It was proposed that every customs district should have one field-officer assigned to it in order to implement control and surveillance over the frontier, and to check the distantsiyas and the frontier guards’ post. In order to satisfy religious needs and for the provision of medical assistance, it was considered necessary that each customs district on the planned frontier surveillance line have one priest, two pslam-readers, and one doctor with a civilian paramedic at every frontier distantsiya with a necessary quantity of first aid supplies.

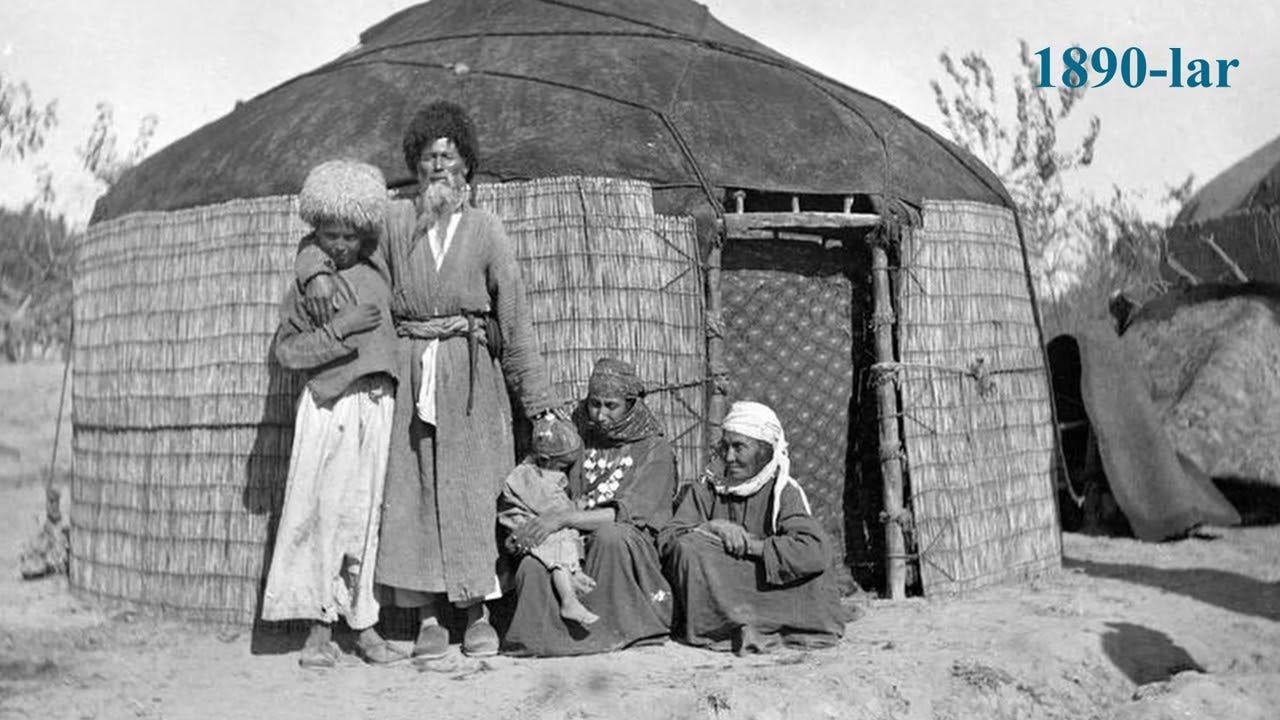

The plan was to hose the personnel at the posts in kibitkas10 and temporary buildings, except for 5 posts (Kyzyl-Arvatsky, Askhabadsky, Gaudansky, Kaakhkinsky and Serakhsky), which were located at points where spaces in homes could be rented, at a cost of 300 to 500 rubles per year. The purchase of 150 kibitkas (for 50 posts, with 3 kibitkas for each post) cost the treasury 13500 rubles, in other words, 90 rubles for each kibitka.

In order to achieve greater success in the organization of frontier surveillance and in the persecution of contraband smuggling on the rivers Amu-Darya and Panj, it was considered necessary to equip the customs and posts, located along the shores of these rivers, with small, shallow kayaks (boats) of a local type, which could be used by the frontier guards and customs inspectors for service.

The proposals for the organization of frontier surveillance in Middle Asia were considered by the State Council on 13th April, 1894. Additionally, it was proposed that the following staff should be added to the frontier guards:

- 2 field-officers for management of the distantsiyas

- 2 ober-officers for assignments in the districts

- 9 ober-officers for commanding the distantsiyas

- 2 medical doctors

- 319 additional personnel of lower ranks (298 cavalry, 21 infantry)

- 472 dzhigits, hired from among the local residence, on the condition that they would not out number lower ranks among the frontier guards at the posts.

Field-officers were given the same rights as OKPS brigade commanders and were named as superintendents over frontier surveillance in the districts, while the heads of the distantsiyas were given the rights of corps department commanders.

It was also imagined that in every district at the most convenient points on the border two mobile Orthodox churches would be established for the customs officials.

On the 6th of June of the year, the proposal for frontier surveillance in the Trans-Caspian Oblast and in Middle Asia on the right bank of the river Panj and Amu-Darya was approved by his Highness the Emperor.

From the very beginning, the insufficient number of ober-officers available for assignments under the heads of each frontier surveillance unit (there was supposed to be one ober-officer for each unit) detrimentally affected the process of organizing the service. They were unable to cope with the flow of correspondence, not to mention in-person inspections of the border, where they were supposed to regularly travel to. Therefore, throughout the year four additional ober-officers were added to each frontier surveillance area (8 in total).

With the establishment of frontier and customs surveillance in Middle Asia in 1894, there was still no establishment of permanent frontier surveillance in the port of Kransovodsk itself, due to the insignificance of its commercial activities.

Not far from Kransovodsk located in a closed bay was the port Uzun-Ada and its customs house, where during this time nearly all exports and a significant part of imports of the Trans-Caspian Oblast were funneled through, as well as nearly all transit between European Russian and the Caucasus on one side and Persia, Afghanistan, Bukhara and the Turkestan region on the other.

With the increased turnover of cargo in the port of Krasnovodsk, the decision was accepted for the monitoring of seaborne traffic arriving to it and the organization customs surveillance for foreign trade. One customs official from Uzun-Ada was sent to Krasnovodsk with the necessary number of customs inspectors. However, these measures turned out be insufficient for identifying and seizing contraband. Therefore, the local customs commander recognized the necessity to establish in the port of Kransovodsk a reliable system of frontier surveillance under the command of an officer of the frontier guards service with a sufficient number of cavalry from the lower ranks. The commander of the Trans-Caspian Oblast agreed with this proposal.

The necessity of urgently establishing reliable frontier surveillance over the Kransovodsk port and its surrounding area was understood by the Ministry of Finance. Initially, based on previous research carried out in the area of Krasnovodsk, the frontier surveillance posts closest to the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea were set at: Kazandzhik, at a station of the Trans-Caspian railway of the same name, located 174 verstas11 from Uzun-Ada, and Chakan-Kala, located right one the Persian border at a distance of more than 150 verstas from Chikishlyar. The Chakan-Kala post was located in a gorge, leading to Persia, it consisted of only a Cossack barracks, surrounded by a high wall with four two-storied towers on its corners.

From these posts, on the direction west towards the Mikhailovsky bay, patrols were dispatched to monitor the routes going to Khiva and crossing over the railway line at Ushak and Balla-Ishem. But as the year long experience of frontier surveillance had shown, such patrols turned out to be not very effective because of the shortage of personnel at these posts (at Kazandzhik: 4 lower ranking officials and 8 dzhigits, at Chakan-Kala: 4 lower ranking officials and 7 dzhigits). Additionally, the length of the line that needed to be guarded made it difficult to provide reliable coverage for all of it. Therefore, the actions of these posts were mostly limited to carrying out frontier service in the area immediately located near their points as well as in the spaces between neighboring posts. Thus, the entire eastern shore of the Caspian Sea between Krasnovodsk and Chikishlyar did not have any frontier surveillance.

Part 2

Due to this it was deemed necessary to establish frontier surveillance in Krasnovodsk itself and along the nearest coastline, and for this it was proposed to add to the staff of the Trans-Caspian surveillance 1 ober-officer as commander of the distantsiya, 22 cavalry of the lower ranks (2 wachtmeisters12 and 2 senior posts), 5 infantry guards and 1 civilian medical paramedic on contract. They were provided with 2 boats for coastal patrols along the Caspian Sea and 2 felt kibitkas to be used as mobile sentries on the most dangerous routes movement by contraband smugglers.

For a higher quality of frontier surveillance over the transportation of goods along the Trans-Caspian railway line, from the Uzun-Ada station, where such surveillance was entirely absent, and for strengthening security of the demarcated border itself, it was necessary to add one more distantsiya headed by an ober-officer to the existing Trans-Caspian frontier surveillance system. Thus, out of the 5 distantsiyas already in existence, it was planned to create 6th with a more uniform number of posts in each distantsiya. At this time only the Akhal-Tekinskaya distantsiya had 9 posts, located across a space of 300 verstas.

It was also necessary to add to 4 lower ranks of infantry as civil servants to the 4 previously appointed ober-officers.

Having considered these proposals, the State Council decided: The existing frontier surveillance in the Trans-Caspian Oblast would be strengthened by: 2 commanders of the distantsiya from among the ober-officers, 1 hired civilian paramedic, 31 lower ranking officials including 22 cavalry and 9 infantry. The distribution of the additional ranking officials within the Trans-Caspian Oblast was provided for by the Ministry of Finance. The order entered into force on 22 January, 1896.

It must be noted that the frontier surveillance established on the border with Persia and Afghanistan had significant differences from what was constructed along Russia’s European border or in the Caucasus. The difference was that it attracted personnel from lower ranking frontier guards as well as locally hired dzhigits (natives), which for the most part did not know how to speak Russian, did not meet the requirements and discipline for service, and were distinguished by the independence in will and laziness. In the first year alone, nearly 100% of the dzhigits had to be replaced, despite the fact that they were accepted into the service by the local administrative authorities.

The organizational structure of frontier surveillance was not divided into departments and detachments, consisting of units from all parts of the frontier guards that were normally commanded, but divided based on the distantsiyas, each of which being subordinated to an officer. The distribution of the posts did not provide complete cordon cover of the border, as the posts were only located at the most important trade routes and open crossing points across the rivers located along the frontier.

Inconsistencies were identified in terms of the number of posts and the number of personnel stationed at them, and the local conditions, including the length of the border area that needed to be guarded. There were not enough forces and supplies at the posts for reliable interdiction of contraband.

During the practical organization of frontier surveillance in the Middle Asian region it became clear that in terms of trade and customs, the border of the Trans-Caspian Oblast and Turkestan were incomparably more important than previously thought. Not only was there a huge volume of trade on the Bukharan-Afghan frontier with Afghan and Anglo-Indian goods, but there was also a very active trade in contraband goods too.

On the Trans-Caspian’s land border, which ran more than 1650 verstas, frontier surveillance was only established on a stretch of 775 verstas and covered 21 frontier posts, while the remainder of the border was entirely open. The space between the cordons were very large and on average there were separated by a distance of 15 to 75 verstas, and sometimes reaching 90 verstas. Moreover, the posts were involved with escorting goods in transit from the border to the customs and back, and some guarded the main trade routes used by contraband smugglers than ran to Askhabad and Merv. The rest of the dry land border, from the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, from Krasnovodsk to Chikishlyar, remained unguarded due to the area being sparsely populated and deserted. The layout of frontier surveillance posts along the border, especially in the Trans-Caspian Oblast, did not present a particular risk of “intruders”, even in the parts where these posts were located. But as these posts were laid out on extremely rugged and mountains areas and were at a significant distance from one another, without constant and reliable communications, there was little could they could do to assist each other in countering and arresting contraband smugglers.

On the Bukhara-Afghan border transport of contraband goods was also carried out not out in the open across river crossings in frontier areas where customs and frontier posts were located, but in areas in between posts, across spaces that stretched 70 to 90 verstas and were concealed by dense thickets of tall reeds that help hide violations of the border and the secret transport of goods. Frontier surveillance along the rivers Amu-Darya and Panj was significantly weakened further due to the absence of reliable means of communication along the line of posts. Other than horse riding there were no other means of transport and communication. Between customs posts and surveillance posts, all outgoing and incoming correspondence, sums of money, parcels and telegrams that were transported by officials of the frontier guards (the so-called frontier mail) by pack horses 15-16 times a month. All of this had to be escorted and guarded by a strong convoy, and this greatly distracted the frontier guards from completely the more immediately task of guarding the frontier. Additionally, the timely delivery of communication was hindered by the lack of well-equipped and safe crossings over the rivers Surkhan, Kafernigan and Vakhash.

The unsatisfactory organization of medical and sanitary affairs greatly damaged the cause of guarding the border. The previously recommended method of using felt kibitkas turned out to be completely impractical. Accommodations in felt kibitkas for people unaccustomed to the nomadic life turned out to be not only uncomfortable, but also extremely difficult and even harmful to their health. During the summer temperatures of these places reached 35-40°C and caused insatiable thirst and the excessive drinking of water. The kibitkas also had drafts that were harmful to a person’s health, while during the autumn and spring it rained often causing dampness, and in the winter cold affected the health of frontier guards and caused fevers. Additionally, these posts were very much in remote locations, which did not allow for timely medical assistance.

With the massive length of the cordon line and the absence of other means of communication, a part from riding along the Amu-Darya and Panj, doctors of the Turkestan frontier surveillance force, even in emergency cases, would need at least a month to reach the frontier’s left flank.13 In such cases even a simple illnesses became complicated and took on acute forms. Therefore, the earlier proposed method of providing medical assistance, based on one paramedic for each distantsiya and one doctor per headquarters of the frontier surveillance, turned out to be insufficient and not appropriate for the local conditions.

Middle Asia’s frontier surveillance organizational command structure turned out to be equally unsatisfactory. Control over the lower ranking officials and their management was not carried out consistently. Control and supervision of the frontier was not constant nor effective due to the disproportionate vastness of the areas entrusted to them (from 150 to 400 verstas). During the first years of the existence of frontier surveillance in Middle Asia the number of staff officers increased by 2 in each district, 2 additional commanders per distantsiya, and the headquarters was moved from Tashkent directly up to the border. Despite all of this, the state of affairs did not improve.

Considering all of the experience gained in managing the surveillance of the Trans-Caspian Oblast and along the rivers Amu-Darya and Panj, the decision was decided to make two common units of the Separate Corps Frontier Guard, which created the brigades Trans-Caspian and Amu-Darya, and adapting them to local conditions, and increasing their existing numbers of officers and lower ranking officials.

It was also planned to replace the lower ranking officials of the frontier guards with hired dzhigits, leaving the limited number of those who remained as translators. New medical brigades were organized in conjunction with the creation of new medical institutions. The kibitkas were replaced by service buildings to be used both as posts and as bases for brigades. For the organization of uninterrupted communications along the cordon line and customs, and for the transport of postal correspondence, medical supplies and state cargo, detachments were supplied with appropriate means of land transportation, while some posts were given sail boats, and the brigade on the Amu-Darya was given a steam ship. Having taken into account the accumulated experience acquired from the first years of guarding the border in the Trans-Caspian Oblast and Turkestan, the Ministry of Finance understood the importance of establishing uninterrupted, high quality surveillance across the frontier. The increasing stream of contraband made it necessary for a more tightly covered border line from Krasnovodsk to the foothills of the Pamir, on a distance of nearly 3000 verstas.

The section of the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, between Krasnovodsk and the mouth of the river Artek ran nearly 400 verstas, consisting mainly of places unsuitable for permanent human settlement due to the shifting sands and the lack of fresh water. The shallow waters of the coastal strip made it unreachable for mooring ships which could cross the Caspian with contraband goods from the Persian shore to ours. Therefore, for this section it was considered sufficient to establish 8-9 individual strong and well equipped frontier posts that were equipped with boats, at points on the coast where would have been convenient for contraband ships to land.14 There were two similarly unfavorable conditions for continuously coverage on the Middle Asian border, first from Caspian Sea along the river Artek, at a distance of nearly 230 verstas, and the second was from the Kushka fortress, along the Afghan border, up to the river Amu-Darya, which covered a distance of nearly 360 verstas. At these sections, as according to local conditions, it was possible to establish only a few separate frontier posts at points that had wells with drinkable water and which were placed on the side of the main trade and contraband routes. A large part of this deserted and waterless border was impossible for permanent settlement during the summer months, but as experience showed, it remained accessible for camel-borne cargo to transit through. The area was supposed to be guarded by increasing the number of existing posts located on the routes that led to Khiva and Bukhara, along the second line inside of this region.

For the purpose of preventing the penetration of contraband along the remaining sections of Middle Asia’s land borders, passing within the Trans-Caspian Oblast (nearly 1000 verstas), and in Turkestan along the shores of the rivers Amu-Darya and Panj (nearly 900 verstas), where localities were more or less settled, it was necessary to increase the density of the guards and establish uninterrupted communications between the frontier posts and cordon. To do this, it was necessary to increase the number of main and intermediate posts, the quantity of people and horses, and to establish new posts on additional section of the Bukharan-Afghan border that was delineated in 1885 by the Pamir Border Commission.

Having taken into account the proposals, on 22 March, 1896, the frontier surveillance and customs districts that previously existed in Trans-Caspia and Turkestan were transformed and made into two brigades of frontier guards, receiving the names: Trans-Caspian – made up of 5 departments, 19 detachments and 70 posts, and Amu-Darya - made up 4 departments, 15 detachments and 51 posts.

To bring the brigades up to existing strength, it was planned to add to them:

For the Trans-Caspian brigade:

- Staff officers – 6

- Ober-officers – 20

- Lower ranking officials – 1228

- Cavalry – 721

For the Amu-Darya brigade:

- Staff officers – 5

- Ober-officers – 18

- Lower ranking officials – 727

- Cavalry – 329

The number of dzhigits was increased from 260 to 472. In the Trans-Caspian brigade there were 127 translators, and 85 in the Amu-Darya brigade, who could be used for verbal translations when necessary during inspections, patrols, and convoying goods.

The formation of new brigades came with the several complexities, such as the lack of prepared additional housing, absences of timely medical assistance, impossibility of purchasing and preparing the required number of riding horses, the need to transfer officers and long serving lower ranking officials from European brigades of the frontier guards, etc. The staffing of the brigades was supposed to done mainly with the most experienced officers from the frontier service in European, Caucasian and Trans-Caucasian oblasts, and partially supplemented by transferring to them forces from the Turkestan Military District and Trans-Caspian Oblast. Therefore, their formation and organization was only carried out gradually, over the course of three years, beginning in 1897 and done so such a manner that they would be able to address the most important tasks of frontier surveillance.

The newly formed brigades of the frontier guards remained subordinated to the commanders of the Trans-Caspian and Turkestan custom district.

Places in the scorching parts of Asia have for a long time been known for their harmful climatic conditions and their detrimental influence on the health of people who are not adapted to live in these southern regions. Fevers are often at the scale of an epidemic, in addition to other illnesses being common across the Trans-Caspian Oblast and Bukhara, namely “Pendinskaya ulcer”.15 This all required the timely organization of medical services in the Middle Asian brigades of the frontier guards. Considering the large distances of the border that these brigades guarded and the absence of proper lines of communication for the transport of the ill, it was urgently necessary to build special medical establishments and the recruitment of a large number of medical workers. For the transportation of patients, it was planned for brigades to use the railway which was relatively close to the line of post along the border, with the railway transporting patients to more distant medical establishments. But for the Amu-Darya brigades, located in large part on navigable rivers, it was decided that they would use steam ships as a means to transport patients.

It was planned to equip every brigade with one central infirmary, in addition to three infirmary departments being added to the Trans-Caspian brigade, at places that were the most distant from the railway, and in the Amu-Darya region, two similar departments on the upper Panj where the river is not navigable.

One of the most important and paramount issue were the measures undertaken to create housing for the frontier surveillance personnel. The initial use of kibitkas as a temporary measure came with great inconvenience and ill effects on people’s health, and thus needed to be replaced with permanent housing. However, the construction of permanent, stone buildings, similar to the ones used in the Caucasus, would have cost 5000 rubles per soldier and 8000 for an officer. Considering the number of posts, the required total sum would have been nearly a million rubles. Therefore, it was planned to use local, cheap materials when possible for the constructing buildings which were to be used for frontier surveillance, and to create adobe buildings for soldiers posted in the Amu-Darya brigade. The costs of these posts would only be 650-700 rubles each. Posts in the Trans-Caspian Oblast were to be constructed with mud brick (as local clay was not of a quality to be used for construction, unlike in Bukharan territories) and they could cost the treasury on average 2000 rubles per post.

Concerning the buildings for brigade headquarters and departments, medical, economic and administrative purposes, for officers’ quarters, brigade churches, etc, they were planned to be constructed mainly with raw bricks. According to preliminary calculations, on the entirely of the Middle Asian frontier there would be more than 80 buildings built for each brigade. Therefore, the project’s plan, the drawings, estimates, and primarily, monitoring of the construction, all required special technicians who would be stationed on the border permanently under direct subordination and at the disposal of brigade commanders, and be held responsible for the successful completion of the tasks. Architects were hired at 2000 rubles a year, with a stipend of 400 rubles for office equipment and 600 rubles for moving.

As the construction of postal buildings progressed gradually and could only be completed within 3-4 years, it was proposed to temporary place of frontier servicemen in kibitkas. Brigades would be equipped with a necessary number of them, which for the Trans-Caspian brigade was 68, and for the Amu-Darya brigade would be 52.

In terms of legislation, the Trans-Caspian and Amu-Darya frontier guard brigades were subordinate to regulations established for the frontier guards in the Trans-Caucasian region.

By the beginning of the 20th century, practically of all the work of creating frontier surveillance in the Trans-Caspian Oblast and in Middle Asia was complete. Later, there were no further structural changes or transformations, except that with time the Russian-Afghan border was covered more tightly from Meruchal to Kerki and in 1912 the management of the 7th district of the Separate Corps of Frontier Guards was transferred from Tashkent to Askhabad.

Appendix (Translator)

On the following page in the thread (9), Vladmal posted additional information regarding the Trans-Caspian Brigade and Amu-Darya brigades. This post mostly consists covers the number of officers and personnel and is better summarized instead of translated.

Headquarters of the Trans-Caspian Brigade was based in Askhabad, a small city of clay building surrounded by fruit gardens.

Distance of 1650 verstas

Average distance guarded:

- Department- 330 verstas

- Detachment – 87 verstas

- Average number of lower ranking officials per 1 versta of border – 0.34

Amu-Darya Frontier Guards - Headquarters at the kishlak (village) of Patta-Kisar, 1.2 kilometers from the right bank of the Amu-Darya, located into the Khanate of Bukhara. Vladmal notes that smugglers often hid on islands on the rivers Surkhan, Kafernigan and Vankhsh, which meant that the frontier guards were especially in need of kayaks in order to monitor these rivers.

Covered distance of 1250 verstas

Average distance guarded:

- Department- 312 verstas

- Detachment – 33 verstas

- Average number of lower ranking officials per 1 versta of border – 0.73

Lastly, the people at Progranec.ru posted the video below on the Youtube channel, the song “And Again we Carry out Frontier Service…” with footage of Russia’s modern day Frontier Service personnel. It’s an interesting look at what guarding Russia’s frontiers actually looks like.

Пограичной надзор

A region in Caucasus. North Ossetia is in Russia, while South Ossetia is a breakaway region from Georgia

Modern day Taurage, in Lativa

Located in modern day Lithuania

Located in modern Poland

The Russian term for the South Caucasus

A Turkic word for a brave, skillful horse riders

An administrative unit used by the Russian Empire in the 19th century, primarily in Trans-Caucasus and in Central Asia

Modern day Turkmenabad

A nomadic tent home, very similar to the yurt

Old Russian unit of measurements. 1 vertsa = 1.0668 kilometer or 3,500 feet

“Вахмистр”, or Wachtmeister. NCO rank of Germanic origin, meaning “watch-master”

This refers to the upper Amu-Darya region

For a fictional example of this, see Hero of our Time, chapter “Taman”

Also known as “Кожный лейшманиоз” or as “Cutaneous leishmaniasis”, a skin infection transmitted by the bites from sand flies. In severe cases it can resemble leprosy