The Fortress of Herat - Turkestan Vedomosti, 1885

Translation of a military-reconnaissance report on the defenses of Herat during the Panjdeh Crisis

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of the article Герат (Herat) from the newspaper Туркестанский Ведомости (Turkestan Vedomosti), 1885, № 44. The original text can be read here, the article itself is on pages 1 & 2. The source for my translation is from a modernized version of the text (post-1917 reforms), and can be found here.

The article “Herat” was published in the midst of the Panjdeh Incident in 1885, where Russia and Great Britain nearly went to war over the Panjdeh oasis, near the city of Herat. The article gives a short overview of the defensive fortifications of Herat in western Afghanistan, and what the Russian Army could expect if they attempted to take the city by force. According to the article, Herat was the most fortified city in all of Central Asia.

In the 1880’s Russia finalized its conquest of the Turkmen nomads and the Trans-Caspia region, which largely correlates to modern Turkmenistan. In 1881, the Russian captured the Turkmen fortress of Geok-Tepe near modern Ashgabat, and in 1884 the ancient Silk Road oasis of Merv was annexed. This brought Russian power to the northern frontiers of Afghanistan, which had long been a source of conflict between the Russian and British empires in their ‘Great Game’, the 19th century’s imperial competition for empire in Central Eurasia.

Unlike a Westphalian state with clearly defined borders, which was typical to Europe at the time, Afghanistan’s northern border with the Turkmen was not clearly defined, and based more on tribal affiliations and who payed tribute to whom. Thus, the Russians saw an opportunity to enlarge their conquests, and hoped to push the frontier boundary as far south as possible before it could be set by an official Russian-Afghan-British border commission.

In early March 1885, General Komarov, commanding a force of infantry, Cossacks, and local Turkmen tribal levies, approached the village of Ak-Tepe at the confluence of the Kushk and Murghab rivers. There, they encountered an Afghan fort called Pul-i Khishti/Tash-Kopru (Stone Bridge) which controlled the bridge over Kushk River. After short negotiation, the Afghans fired on the Russian force. The Russians responded by storming the Afghan positions and seizing the fort, sending the Afghan garrison of 4000 into flight. Prior, the Russians had made assurances to the British that they would not to attack the Afghans at Panjdeh unless they were attacked first. Some accused the Russians of staging a provocation against the Afghans. Either way, with the Panjdeh oasis now under Russian control, the road to Herat was now open.

It had been a long running fear among the British that Russia had intentions to invade British India, and that Russia’s main axis of advance would be through Herat, then through Kandahar, Quetta and the Bolan Pass. Earlier in the 19th century, British India had been twice thrown into crisis when Persia attempted to conquer Herat in 1838 and 1856. The British believed Persia was a semi-vassal of Russia, and thus they thought if Herat was under Persian control, its gates would be thrown open to Russia and could serve as a launch pad by Russia for an invasion of the Indian subcontinent. Thus, Russia’s advance on to Herat in 1885 triggered a war scare in both London and Shimla1. Two army corps were mobilized in India and were prepared to march to Herat in order to defend it from Russian assault, and the Royal Navy was likewise prepared for global operations against Russian Navy.

The crisis was ultimately resolved peacefully. In 1887, the Joint Afghan Boundary Commission set Afghanistan’s northern border largely unchanged from what Kabul claimed, except for the southern bulge, which included Panjdeh, that was carved out by General Komarov, now apart of modern Turkmenistan.

The Panjdeh Incident is an interesting case of how actions taken by a Great Power’s forces operating on a distant frontier can risk provoking a general war. A similar colonial crisis would erupt in 1898 between Britain and France over the upper reaches of the White Nile, known as the Fashoda Incident. This problem especially plagued American and Soviet policy makers during the Cold War, who feared an ally or a proxy state would act too independently and provoke a Third World War. In order to prevent further incidents of the “tail wagging the dog”, modern states, thanks to advances in communication technologies that facilitate better command and control, have established very strict centralized control over their forces.

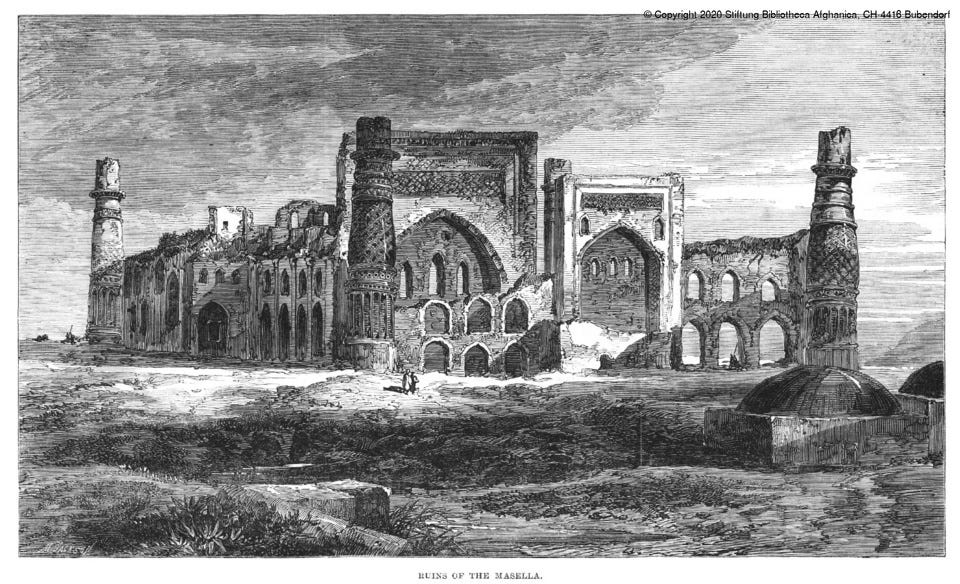

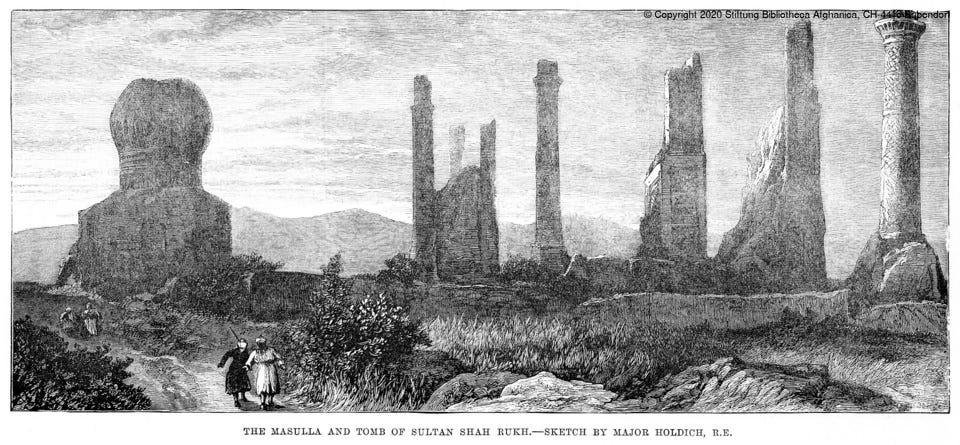

Lastly, the article mentions the Musalla Complex, a very important Islamic heritage site located at Herat. Built by the Timurids in the 15th century, the complex consisted of a mosque, madrassa, a mausoleum and minarets. This site was unfortunately demolished in the course of the Panjdeh Incident, as it would have provided crucial cover to the Russians if they have attempted to storm Herat and its citadel. Today only four minarets remain. Herat’s citadel was renovated from 2006-2011.

For more on the Panjdeh Incident, and the 19th century geopolitics of Central Asia, I would recommend Peter Hopkirk’s “The Great Game” and Alexander Morrison’s “The Russian Conquest of Central Asia”.

Herat

Herat has acquired all the more importance with current events; at the very least, the English are strenuously fortifying it.

Due to the way Herat was built and fortified, it is entirely opposite from other Central Asian cities, which in the majority of cases consist of a group of buildings that are scattered across a vast area, with dilapidated fortifications that are almost defenseless against current and modernized artillery, even those medium-sized calibers. Herat, by contrast, is a first-class fortress, by Asian standards. It can only be taken with a long siege; it walls are laid out as if they were built by a Cyclops, and shells from field artillery will bounce of its walls without inflicting any harm.

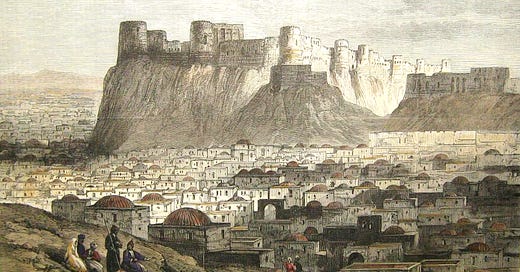

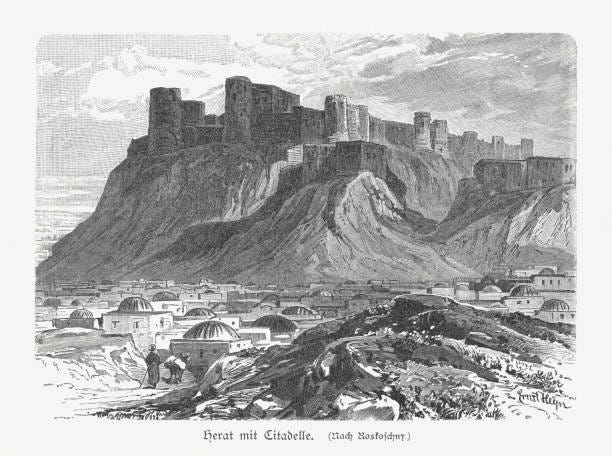

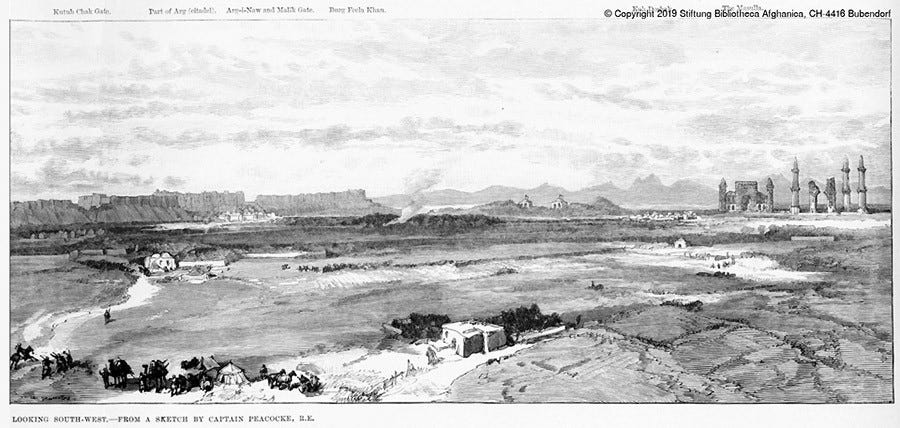

Among the rolling grain fields, in a fertile valley, the irrigated Hari-Rud2 and its entire network of canals, the road rises up to the picturesque ramparts of the ancient Afghan stronghold. They are built on a mighty stone pedestal, 40 feet tall, at a distance of 300 steps from the shore of the river. The right and left of the river valley are encircled by a jagged mountain range with a fantastical outline; but at the same time the mountains dominate over the city which is only a few miles removed, and therefore do not represent any benefits for shelling the city, as if the unknown builders of the Herat’s fortifications had a presentiment about the invention of long-range artillery. Of course, according to modern understandings, the fortifications of Herat are outdated, but they will still preform their function. Centuries have passed by without leaving a trace over these mighty stone walls. Not Saracens,3 not Persians, nor the great Mongols could make the slightest breach in these walls,

Additionally, Herat is extremely convenient for defenders. The entire city has up to 30,000 inhabitants, is a small, almost square-like quadrilateral 600 sazhens4 long, and in width about 600. Six gates interrupt its walls, rising from 60-80 feet above the floor of the valley. Two of these gates – Bab-el-Melik (the royal gate) and Bab-el-Kushk – are unusually rich in architectural decorations. Through each of these gates the path turns through reduits, casemate lunette5 and then turns into a new fort. Above the ramparts, which as a line intersects with 14 bastions and four forts that face north, south, east and west; they are called Abdul-Ment, Kurrrm-Bey, Kuttab-Chamk and Fellekh-Kan. At the end, in the very center of the city on a sheer cliff stands the citadel, named “Ark”, dominating the view far across the landscape over the river and valley. This – Herat’s equivalent of Gibraltar, which, it seems, can be taken only by starving its defenders or by inducing someone inside to commit treason, which is more in line with the customs of this country. It must be added, that all the forts and fortifications are built in such a way that allows the defenders to lay down mutual cross-fire on the approaches to the citadel, so Herat can be held even if the enemy successfully breaks through and storms the outer line. But this is far away.

The approaches to Herat are very difficult for the attacker, especially from the north. Before anything else, they have to overcome a defile, which opens to the valley of the Hari-rud; then it is necessary to conduct a forced crossing over the Hari-rud, and this affair is not easy: the bridge is defended by two strong tête de pont (“bridgehead” - defensive fortifications at each end of the bridge).

Pul-i-Khatun was built in the time before the Crusades; it is entirely marble and is spread out on a wide arc on 22 arches across the river, while covering the entire flood plain. The difficulty of taking possession of the bridge is increases even more so because it can be fired upon from the “Ark”, the citadel of Herat. Generally, they say in all of Asia there is not another city where besiegers would be in such an unbeneficial position in comparison to the besieged; the enemy can only reach the city with enormous losses, because the entire surrounding area is does not have even the slightest cover. The terrain is entirely flat, which would facilitate the construction of breaching-batteries.

Until recently, however, there existed a place, which in the case of a siege of Herat, it could serve as a basis for enemy actions, namely – the majestic mausoleum6 of the lord Hussein-mirza-khan and his successor the great Shah Rukh.7 This church8 is among the most respected in the Muslim world and survived among the most wild and devastating wars. Mazylya,[8] as the church is named, consists of a mosque, with a cupola made of yellow and blue tiled bricks, burned under the sun as gold. The number of minarets is 21. This is the richest building of Muslim construction; it is more than three times larger than the 7 heights of the Kaaba in Mecca. Of course, time has not passed without a trace for Mazulya, but now she still represents a wonderful sight, with its giant gate and the entire forest of slender, thin minarets. And here – Goldig and Pikok, majors in the British service, who came to strengthen Herat, found that Mazulya could serve as cover for an enemy force. British “civilization” destroyed this site, which had been spared by the wild hordes of Chingis Khan. In 4 hours, with no small help from dynamite, the wonderful monument of Afghanistan disappeared without a trace!..

Summer capital of British India

A river flowing westwards, flowing past Herat, towards Mashed in Iran and the Kyzylkum Desert in Turkmenistan

Old word for Muslim Arabs

Old Russian unit of measurement, about 2.1 meters

Fortified gun emplacement (modern equivalent would be a bunker), a lunette in particular is a crescent moon-shaped firing position for artillery

Musalla complex

Son of Timur, ruled the Timurid Empire from 1405-1447

Not literally a church, but the Russian word used is “храм”

I still weep for the Musalla Mausoleum. As Robert Byron put it in ‘The Road to Oxiana’:

“This array of blue towers rising haphazard from a patchwork of brown fields and yellow orchards has a most unnatural look. […] it can be seen from the insides of these minarets, where the tilework stops short some forty feet from the ground, that they were originally joined by walls or arches and must have formed part of a series of mosques or colleges. What has happened to these buildings? Things on this scale may fall down, but they leave some ruin. They don’t vanish of their own accord without trace or clue, as these have done.

It is a miserable story.”

Very nice.