The History of Yenisei Kyrgyz and their Trade - Sergey Kiselev, 1947

Translation of an Archaeological Essay on the History of Yenisei Kyrgyz and their Commerical Relations

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Below is a translation of an essay detailing the history of the Yenisei Kyrgyz and their commercial relations, based on archaeological findings. The Yenisei Kyrgyz were a small, but not insignificant people, who lived along the Yenisei River in southern Siberia during the Middle Ages. They are best known historically for annihilating the Uyghur Khaganate in 840 and sacking the capital Ordubaliq, located in the middle of the Mongolian plateau, putting the city to the torch and scattering the Uyghurs in all directions. Prior to this, the Uyghurs had been the greatest and most powerful of all nomadic states to rule the steppes before the coming of the Mongols, but their empire was gone in an instant as a result of the Kyrgyz’s bolt from the blue.

The author, Sergey Vladimirovich Kiselev, was born on 17th July, 1905. In the 1920’s he studied at the Moscow State University and later worked at the Moscow State Historian Museum. Kiselev took part in several very important archaeological expeditions across south Siberian and the steppes lands immediately to the south. Most notable, from 1948-1949 he led the expedition to excavate the ruins of Ordubaliq, as well as Karakorum, the Mongol capital, and other settlements in Mongolia. Ordubaliq had been discovered prior, by Nikolai Yadrintsev and Vasily Radlov in 1891, but Kiselev was the first to scientifically explore and study the site.

The Yenisei River valley, and mainly the Minusinsk Basin, was the homeland of the Yenisei Kyrgyz. The Yenisei River begins in the Sayan Mountains, on the up land plateau region of Tuva to the south of the Minusinsk Basin. From there, the Yenisei flows northwards, through Siberia before eventually discharging into the Arctic Ocean.

The Minusinsk Basin can be classified as a steppe-forest region, which allowed the Kyrgyz to practice a mixed economy of both pastoral semi-nomadism and hunting, along with some agriculture. It is believed the Yenisei Kyrgyz were initially a Samoyedic speaking people, but were gradually linguistically Turkicified as a result of influence of from their powerful southern neighbor. According to Chinese sources, many Kyrgyz had green eyes and red hair, with only some having Asiatic features. The Yenisei Kyrgyz are now know today as the Khakas people, and the territory of the Yenisei Kyrgyz today is mostly within the Republic of Khakassia, within the Russian Federation. Additionally, the Yenisei Kyrgyz should not be confused with the modern day Kyrgyz of Kyrgyzstan. They are different peoples, and I do not yet understand how and why the ethnonym “Kyrgyz” was applied to both peoples.

The history of the Yenisei Kyrgyz was intimately interlinked with the history of the Turkic Khaganates, which were based on the steppes of the Mongolian plateau. The Kyrgyz were divided from the steppes by Tuva, a mountainous plateau region. Tuva represented a major geographic barrier between the two, and the Turks constantly attempted to hold the region as a buffer territory between themselves and the equally militaristic Kyrgyz. During the Uyghur period when the conflict with the Kyrgyz intensified, several major fortresses were built across Tuva. The most famous of these is the Por-Bazhyn complex, a fortified palace located on Lake Tere-Kol. The Uyghurs built these fortresses in the course of their wars against the Kyrgyz. But overtime the Uyghur’s state was weakened due to political infighting and growing decadence among the ruling tribes. In the end these fortresses were all for naught. In 839, after a particularly intense episode of fractional fighting within the Uyghur court, a Uyghur general defected to the Kyrgyz and led them back over Tuva on to the steppes, where they put Ordubaliq to the torch. The Uyghur Khagan perished and the tribes fled in all directions, namely going to the Tarim Basin, the Hexi Corridor and the Chinese frontier. Over the next century, the Kyrgyz and Manchurian Khitans drove the remaining Turks off the Mongolian plateau, forcing them to seek new lands in the west. The downfall of the Uyghur Khaganate resulted in the Turks losing their homelands, created a vacuum that was later filled by the Mongols. For more on the Yenisei Kyrgyz and the Uyghurs, see my essay on Substack, The Collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate and the Uyghur Migration across the Silk Road.

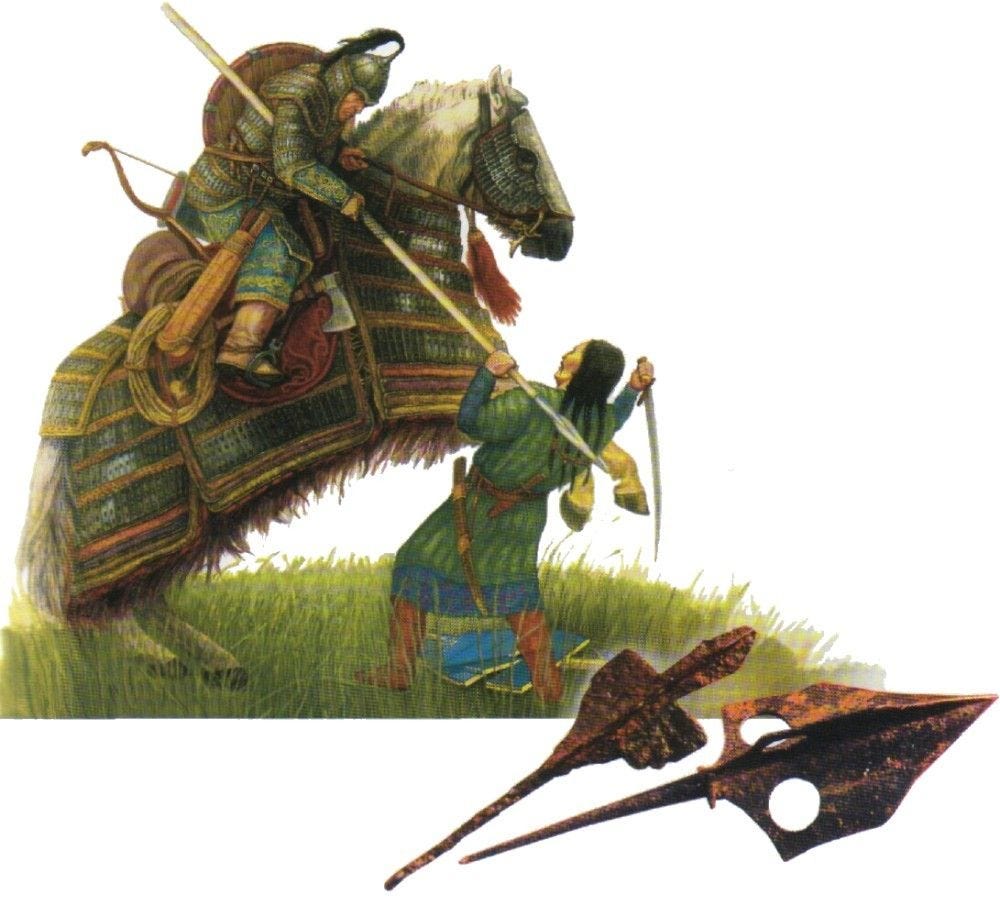

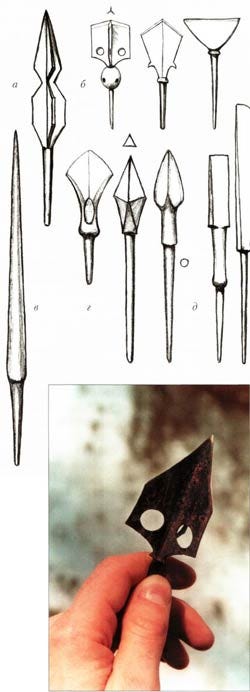

Unfortunately our knowledge on the Yenisei Kyrgyz is very limited. Located on the furthest edge of the civilized world, the Kyrgyz were very distant from China, and main literary power in pre-modern East Asia and sources of much of our information on the Turks, Tibetans and others, and thus little was written about them. This makes the archaeological findings all the more important. As Kiselev details in the essay below, despite their remoteness, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were deeply integrated into the trade routes of the “Silk Road”. They primarily exported furs along with other musk, birch, tusk and metal products. Their main trade partners were the western Turks, those occupying the Semireche region in the southeast of modern Kazakhstan, the Tibetans and the Arabs. Most interestingly, it appears the Kyrgyz were excellent blacksmiths, as indicated by the vast finds of arrows. Their excellent metal craft production would have served as the material basis enabling them to challenge the Turks, and ultimately defeat them at the height of their power.

Yet the text has one notable mistake. Kiselev falsely discusses the Kyrgyz as having an empire on the Mongolian plateau after 840, and that the Kyrgyz ruler relocated his residence there. None of this is true. The Kyrgyz raided and sent embassies to China across the steppes, but they never attempted to establish themselves in the region. For a full explanation of why the Kyrgyz chose to remain in south Siberia, see the essay “Breaking the Orkhon Tradition: Kirghiz Adherence to the Yenisei Region after A.D. 840” by Michael Drompp. Drompp has written extensively on the Yenisei Kyrgyz, and interested readers are encouraged see his other work, including his most excellent book “Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History”.

This essay was published in journal Краткие сообщения Института истории материальной культуры (Short Reports of the Institute of History of Material Cultures), volume 16 pages 94-96. Source for the translation can be found here. Page numbers, as according to the original publication, are stated in brackets. I have included all the original footnotes untranslated in Russian, and added a few additional footnotes explaining certain details. Also, a catalog of Yenisei Kyrgyz arrow heads can be found here.

The History of Yenisei Kyrgyz and their Trade

(page 94) The complex system of Kyrgyz crafts, which we have repeatedly written about, to one degree or another, were oriented towards exchange, and in turn was stimulated by it. Already it has been noted, that close ties between Kyrgyz blacksmith crafts and exchange are indicated by the wide spread of Kyrgyz produced iron tipped arrow heads in neighboring regions in Siberia. This is confirmed not only their complete similarity with findings from the Yenisei region, but also the fact, that nowhere has such a number of finished and unfinished (unsharpened) arrows been found elsewhere other than in settlements of Yenisei Kyrgyz blacksmiths. This can also be said about the Kyrgyz foundry works. Chinese statements on the high quality of Kyrgyz weapons suggest their spread on to international markets, and to the court of the Chinese emperors. The strong trade ties the Kyrgyz had with others, for the exchange of their metalworking crafts, made them independent and represented a very important industry in their economy.1 Besides iron products, the Kyrgyz traded gold and furs – riches, that are especially noted in the sources.2 The connection between the Kyrgyz with Asian markets persisted until the 9th - 11th centuries. In particular, Arab merchants had good knowledge of the routes to the country of the Kyrgyz. Along with the previous mentioned trade goods that were exported from the country of the Kyrgyz, musk was significant as well. Thus, in the 10th century Ibn-Khaukal noted, that the best musk in terms of quality and prices came from Tibet and from Kyrgyz regions. In the famous “Tuman Manuscript”,3 written in Persian in 982-983, it is reported that birch and tusks, which were used for knife handles, were exported from the Kyrgyz. It is possible, that the tusks were walrus tusks, which the Kyrgyz resold after receiving it from the north.4

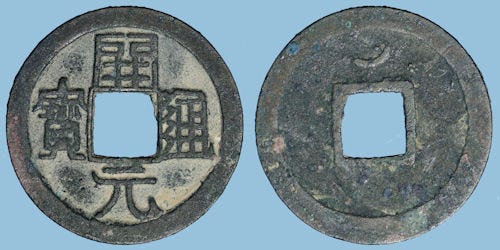

Regarding the trade of birch, this matches with statements by the Chinese, that the Kyrgyz “grow birch most of all”.5 They likely sold it to China. Imports by the Kyrgyz are represented by archaeological data. From China, for example, they imported metal products – plow blades, harness accessories (even stirrups), decorations and mirrors in especially large quantities. Interesting conclusions about relations with China in the context of the changing foreign policy position of the Kyrgyz can be made based on numismatic finds in the Minusinsk Basin. For this we relied on the collection (page 95) of Chinese coins at the Minusinsk Museum.

During the terrible times of China’s history, prior to the epoch of the Tang Dynasty,6 relations with the north were, naturally, very limited. Very few Chinese coins reached the Yenisei during that time. This can be said as only four coins have been found, from the 5th century (Western Wei Dynasty 544 AD).7

Clearly, the military weakness of China and the hostility on the side of the Rouran and Turks8 in the first period of their rule created a serious obstacle for the Kyrgyz to communicate with China. The situation became completely different in the 7th century, when in the 20’s the Tang Dynasty conquered the lands of the Eastern Turks. Trade increased, and this is noted by 45 coins of the Tang Dynasty minted in 621, found in different places in the Minusinsk Basin.9 However, the Orkhon10 Turks liberated themselves from the Chinese, an uprising which began in 661-663 and ended with the restoration of the self-ruled Khaganate11 in 682, again making it difficult for the Kyrgyz to communicate with China. Among the finds in the Minusinsk Basin there are no Chinese coins from the second half of the 7th century, nor form the first half of the 8th century, when the Turks were not only greatly strengthened, but had entered into a struggle against the Kyrgyz. Chinese chronicles, however, report about repeated Kyrgyz embassies to the court of the emperor during this time.12 But, of course, these were diplomatic missions with the goal of coordinating the struggle against a common enemy – the Turks, and trade could not have been significant. Kyrgyz trade connections with China were also weakly developed during the Uyghur domination. However, in the first years of their rule – 758 and 759 – there were finds of 13 coins,13 but this could be explained that the new rulers of Central Asia had insufficient control of the trade routes. Only later on does the Minusinsk collection have 6 coins, from 780.14 It must be remembered, that the Chinese chronicles note that after 758 when the Uyghurs conquered the Kyrgyz, “Khyagas15 embassies could no longer reach the Middle State16”.17 But here comes a sharp turning point in the history the Kyrgyz. Their forces smashed the Uyghurs, and the Kyrgyz khan “transferred his residence to the southern side of Laoshan Mountains (likely, Tannu-Ola18”.19 This happened around 840, and it immediately allowed for a strengthening of the ties to China. A record number of coins were found in the Minusinsk Basin dating from 841 to 846 - 237 copies.20 The increase in Kyrgyz trade with China in the 9th century undoubtedly was connected with dominant position of the Kyrgyz in Central Asia. However, this did not last long. Under pressure by the Khitan at the beginning of the 10th century, the Kyrgyz were forced to leave the regions south of Tannu-Ola. The connection with China was again severed. From the middle of the 10th century, the Minusinsk museum has only four coins.21 Only at the end of the 10th century and in the 11th were relations again revived, and again Chinese coins began reaching the Yenisei. In all, 37 coins from the Song Dynasty and 3 Japanese coins from 1091 were collected.22 In the 12th century, with the dominance of Jin Dynasty in northern China, there was no revival of communications between the Kyrgyz and China. In the Minusinsk collection there are merely (page 96) 8 Jin coins, found in only a single place, around the village of Kaptyrevo.23 Seemingly, the political situation in Central Asia at this time did not allow for the development of Kyrgyz-Chinese relations. Finally, the formidable 13th century arrived. In the Minusinsk collection there is not one coin from this time. There is only one Yuan coin from the middle of the 14th century.24

Except for this single find, it can be said that as a result of the Mongol’s defeat, Chinese coins disappeared from the Yenisei for nearly 400 years.25 Only in the 17th century do they appear again, in small quantities (only 12 specimens were found, minted between 1621 and 1628).26 A revival in the 18th century was to be expected. In the Minusinsk museum there are 49 coins from this time.27 The interest the Kyrgyz had in trade also affected their western connections. Different from many Central Asian peoples, the Kyrgyz, in the words of the Chinese, had friendly trade relations with the Karluks (Gelolu), Tibetans (Tufan), Tocharistan28 (Dakhya), and the Arabs (Dashi).29 The Kyrgyz sold them their “works” and received from them valuable goods. The Chinese were well aware of this trade. Such details were even known to them, that “the Tufans (Tibetans) when in communication with the Khyagas, are afraid of robbery by the Uyghurs, which is why they take escorts from the Gelolu30”.31 The Chinese chronicler also knew that the Kyrgyz received “from the Dashi, not more than 20 camels came with patterned silk fabrics; but when it is not possible to fit all of it in, they spread it out across 24 camels. Such a caravan was sent once every three years”.32 In another place the same historian reports, that the fabrics were brought to the Yenisei not only from the Arabs, but also from Kucha and Beiting, also known as Beshbaliq, which belonged to the Uyghurs.33 This shows that, despite the hostiles between the Uyghur khans and the Kyrgyz, the Kyrgyz still traded with the Uyghur cities in eastern Turkestan.34

This was awkward to translate, the original is: “Укреплявшаяся связь кыргызских металлообрабатывающих ремёсел с обменом делала их самостоятельной и очень важной отраслью хозяйства.”

Иакинф. Собрание сведений о народах, обитавших в Средней Азии в древнейшие времена, ч. 1, стр. 144.

A book by Hudud al-'Alam, a 10th century Persian geographer from Guzgan in modern day northern Afghanistan. It is named the “Tuman Manuscript” because it was discovered by Alexander Tuman in Bukhara, in 1892. The English translation is by Vladimir Minorsky, and can be read here - http://www.kroraina.com/hudud/hudud_al_alam_1937.pdf

Hudud al-Alam «The region of the World» a persian geography 372 a.h. — 982 a.d. Oxford — London 1937, p. 96-97.

Иакинф. Собр. сведений и т. д., ч. 1, стр. 444.

From the fall of the Han Dynasty in 220 AD to the established the Sui Dynasty in 581, China was beset by near constant wars and foreign invasions. The Sui Dynasty was later replaced, almost seamlessly, by Tang in 618

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5620-5623.

The Rouran was a nomadic state that ruled the steppes north of China in the 4th and 5th centuries. They were later replaced by the Turkic Khaganate

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5295-5339.

Orkhon refers to the Orkhon River on the Mongolian Plateau, which was the center of the Turkic Khaganate

Known as the Second, or Eastern, Turkic Khaganate

Иакинф. Собр. свед. и т.д., ч. 1, стр. 448 и сл.

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5264-5268, 5617, 5618 и 5709, 5710, 5716, 5718, 5720.

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5711-5715, 5717.

An older way to write Khakas, the modern ethnonym for the people of the Minusinsk Basin

Chinese refer to their own country as the “Middle State”, or “Middle Country”, which in Chinese is Zhongguo 中国. The word “China” is likely derived from the old Arabic word for China, which is Sina

Иакинф. Собр. свед. и т.д, ч. 1, стр. 449.

A mountain range in southwestern Tuva

Там же, стр. 450.

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5340-5558, 5279-5290, 5816, 5884-5886 (последние четыре — из Тюхтятского клада). Кроме того, одна монета найдена В.П. Левашовой в кургане №19 II группы Капчелов в 1935 г.

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5291-5294.

Хранятся там же, инв. №5569, 5574-5609 и 5652-5664.

Хранятся там же, инв. №5610-5616 и 5619а.

Хранится там же, инв. №5619.

This likely refers to the fall of the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty in 1368, which naturally would have resulted in a total decline of trade across the region

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, инв. №5624, 5625, 5627-5636.

Хранятся в Минусинском музее, ннв. №5637-5651, 5655-5708.

Ancient Bactria, modern Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan. The name Tocharistian comes from the Tocharian speaking Yuezhi who conquered the region around 140 BC

The names in brackets were the Chinese names for these peoples

The Uyghurs were in conflict with the Tibetans, Karluks and Yenisei Kyrgyz at the time

Иакинф. Собр. свед. и т.д., ч. 1, стр. 449.

Там же, стр. 449.

Там же, стр. 445.

This statement is only partially true, and is based on a misunderstanding. During the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghurs and Tibetans fought over Beiting with neither side gaining a firm hold over the city. Kucha as the time was mostly under Tibetan control. After 840, Uyghur tribes fled to Beiting and Turfan, and established the Qocho Idiqut State, with Beiting/Beshbaliq serving as the Uyghur’s summer capital. Kiselev appears to have mixed up these two distinct periods of Uyghur history. During the Khaganate period, the Uyghurs and Kyrgyz were fiercely opposed to each other. The Kyrgyz likely traded with the Uyghur cities of eastern Turkestan during the Qocho period, as only then were these cities under firm Uyghur control and no conflict existed between the Uyghurs and Krygyz)

I had no idea regular trade routes went so deep into medieval Central Siberia. Especially surprising was "3 Japanese coins from 1091"