The Khazar Khaganate: An Introduction

An Overview of the Empire of the Khazars

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Of all the steppe nomadic empires, the Jewish Khazars have been one of the greatest historical enigmas. A steppe nomadic people comparable to Atilla’s Huns and the Mongols, the Khazars have attracted a great amount of attention for their seemingly bizarre conversion to Judaism. In popular imagination, the Jews, following the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 AD, are often thought of as a people of wandering merchants and theological scholars. The idea that a horde of ferocious steppe warriors and Asiatic nomads living in tents would convert to Judaism is often looked upon as one of the more peculiar chapters in world history.

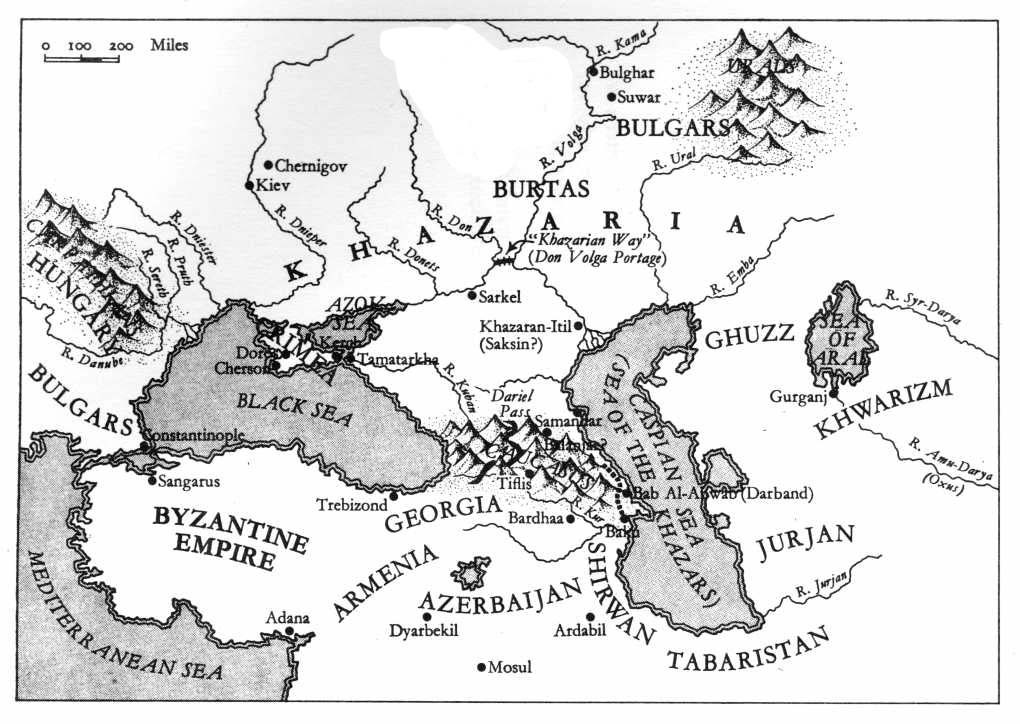

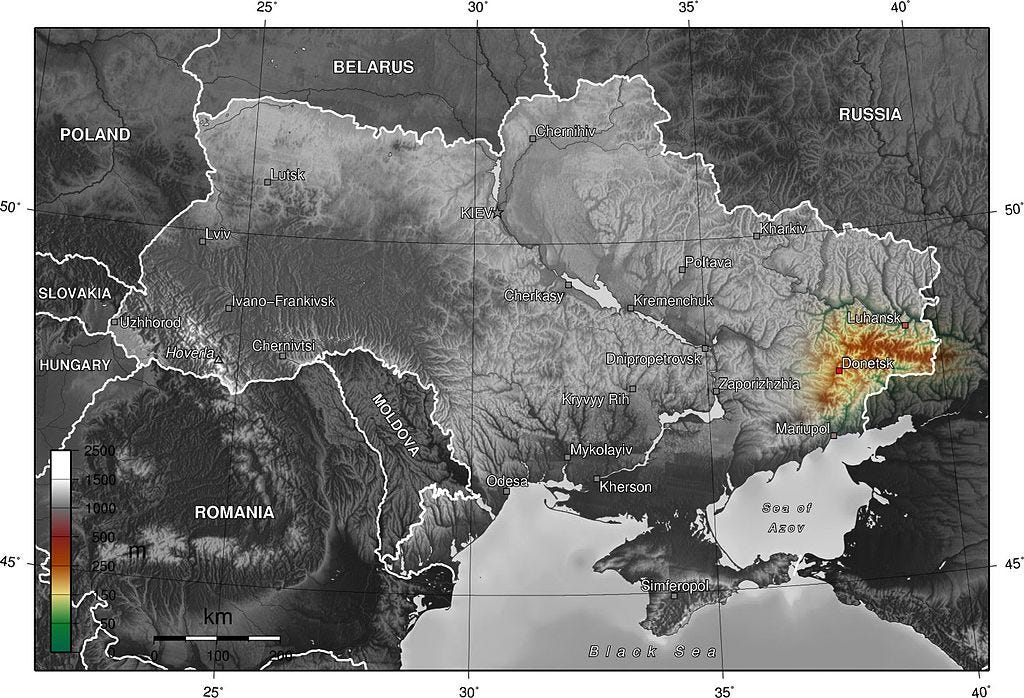

The empire of the Khazars rose to power in the 7th century and disintegrated in the 10th. Predominately a Turkic nomadic people, the Khazars built an empire than covered the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe lands, a region encompassing the grassland plains from Ukraine in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east, the Caucasus Mountains in the south to the forests of modern Russia in the far north. The Khazars dominated the western Eurasian steppes for over 300 years, creating what latter historians have called “Pax Khazarica”. Under the Khazar Peace, security and order were established, creating the conditions for the formation of “civilization” for the first time in this part of the world.

Prior to the coming of the Khazars, the Pontic, Caspian, and north Caucasian steppes had long been the home of nomads. In antiquity the Cimmerians, Scythians, and Samartians had roamed these regions, with a few islands of sedentary life existing within the nomadic sea. The Greek colonial cities on the Black Sea littoral had a complementary economic relationship with these nomadic peoples, but Huns and Turks who began arriving to the West in late antiquity shattered every civilization they encountered. Even among the relatively more peaceful predecessors to Attila and later Turks, the steppe nomads lived in a state of semi-perpetual anarchy.

This was largely a result of their pastoral lifestyle which allowed for a high degree of mobility which prevented any form of lasting state structures from emerging. Often alliances would form between clans, even confederations of clans acting in unison in the pursuit of some goal, but these relationships were highly ephemeral and difficult to maintain. If a clan or grouping of clans was not satisfied with their situation for any reason, they could simply migrate away and exit from whatever political arrangements they had previously been a part of. This of course was only possible because nomads could easily migrate away with their flocks of sheep, cattle, and horses. In fact, their pastoral way of life required them to migrate to different pasture lands throughout the year. This all contributed to the political life of nomads being inherently formless.

In order to illustrate this point, it is worth contrasting the situation on the steppes with conquest and state formation in the sedentary world. The Romans built their empire through conquest, and if a city later rebelled a Roman army would simply recapture the city and punish the leaders of the rebellion. It is not easy to relocate a city or an agricultural community. Cities and farms are stuck at fixed location and exist at the mercy of anyone who can march an army against them. Another example, while campaigning in Central Asia, Alexander was able to conquer the cities and fortresses of Bactria and Sogdia, which brought those peoples under his dominion. Yet, he was unable to conquer to the nomadic Saka beyond the Jaxartes River who could simply flee with their herds and avoid capture.

The inability to permanently conquer and subdue one another prevented the formation of lasting states by nomadic peoples. Of course, Attila created an empire but his empire completely fragmented following his death. The nomadic world was plagued by ephemeral states, anarchy and near constant warfare. Such conditions prevented the emergence of what many would define as “civilization”. In “Politics”, Aristotle says, civilized life is only possible thanks to laws, and laws are the product of families coming together to form a city where such laws can be formalized. Without the city, none of this is possible. The anarchy and constant warfare on the steppe made the creation of urban life impossible. In order to create and maintain cities a large surplus of agricultural goods is required. Additionally, irrigation, a constant supply of drinking water, and other capital intensive pieces of infrastructure are often required. Yet, large scale farming was simply impossible due to the ever constant threat of a nomadic horde arriving and trampling your crops. And without extensive farming no agricultural surplus could be created to feed urban life.

It should be noted that terms like “civilization” and “civilized life” are not exactly the most useful words, and should be used sparingly and with reservation. They are often misleading, and carry with them subjective moral claims. The nomads might not have been “civilized” but their way of life was exceedingly complex in its own right. Moreover and more importantly, the “barbarian” steppe nomads repeatedly throughout history were the conquerors of civilizations to their south despite almost always being vastly outnumbered. These nomads would conquer the decadent and decayed peoples beyond the steppes and become their rulers. The Vikings came to rule the Rus, the Mongols and Manchus conquered China, the Turks conquered Byzantium, and many other such examples exist. In the words of Nietzsche, “the noble caste was always the barbarian caste”. Very often in history the designation of nomads as being savages was nothing more than the moralistic outrages of weaker peoples who could do nothing more. To quote Nietzsche again, “It was the noble races which left the concept of ‘barbarian’ in their traces of wherever they went.” In their state of decay and weakness, the Romans called the Huns barbarians in the same way the Gauls would have viewed the Romans themselves are barbarians centuries prior. For the nomads and other “barbarians”, their “primitive” way of life was the source of their strength. This might seem like a tangent, but these matter are very important to keep in mind when discussing nomads, or any historical matter in fact. Positing moral claims usually only serves to obscure our understanding of historical events and processes.

This state of constant anarchy on the steppes came to a temporary end with the establishment of the Pax Khazarica. For the first time ever in the western Eurasian steppes, irrigation, agriculture, aquaculture, and urban life were all made possible. Cities sprung up on the steppes and over time the Khazars became a partially sedentary people, no longer fully nomadic as they traded in their yurts for urbanized life. Peace also brought with it commercial opportunities, and in time the Khazar Khaganate became an international trading and commercial hub, fully integrated into Silk Roads. The Khaganate became both a center for commerce transiting east to west and north to south, and a major exporter of two of the most valuable commodities in the pre-modern world, furs and slaves. Thanks to the Pax Khazarica, foreign merchants were able to travel safety in the steppe lands of western Eurasia and conduct their business without fear of robbery and death.

The era of the Khazars was one of the great eras for the Silk Road. The rise of the Tang Dynasty in China and the Turkic expansion across the Eurasian steppes inaugurated a period of enormous commercial activity, only in the Mongol era was Silk Road trade greater. Pax Khazaric was crucial for this as it allowed for trade to reach Europe from across the steppes and brought valuable slaves and furs to the south. In addition, the Khazar peace created stability which benefited those civilizations bordering the steppes like Byzantium. As will be seen, Byzantium’s survival in the 7th and 8th centuries was in large part thanks to the Khazars.

The Khazars have always been a subject of particular interest, mainly for their conversion to Judaism. Their conversion appears very strange, but it is actually not as bizarre as it first appears. The exact details of their conversion are largely unknown, and what information that exists is obviously mythological. Nor is it known precisely why they converted, or why they chose Judaism. Several theories and historiographical interpretations exist which attempt to answer these question, but they are just speculations ultimately.

My theory as to why the Khazars converted to Judaism will be answered in the second article of this series. My explanation is quite complex and it will require an entire essay onto itself to be explained properly, but a brief and preliminary explanation should be given. I believe the Khazars converted to Judaism in order to achieve the political consolidation of the Khaganate by increasing the Khaganate’s wealth through greater involvement in world trade and by attracting a people who could serve as administrators. By converting to Judaism the Khazars would both attract Jewish merchants to their realm and leverage the international Jewish diaspora, especially the Radhanite Jews who were a great mercantile people involved with the Silk Road at the time. Increased wealth through greater involvement in the Silk Road was used to tie the disparate subject peoples of the Khaganate around the Khagan. Additionally, the Khazars being a nomadic Turkic people had no traditions of learning or literacy, thus they were poorly suited to be administrators and officials of an empire. By converting to Judaism the Khazars would attract a highly educated people who had abilities that would fill a niche that the Khazars otherwise could not fill themselves. In short, the Khazars converted to Judaism in order to use the Jews to affect the political consolidation of their empire.

The Khazar conversion fits a broader pattern of steppe nomads adopting Abrahamic faiths; the Khazars are hardly alone in this. Many contemporary Turkic empires converted to monotheistic religions just as the Khazars did, and often for similar reasons. In fact, the contemporary Uyghur Khaganate had a nearly identical relationship with the Manichean Sogdians as the Khazars did with the Jews. The only thing that is unique about the Khazars is that they chose Judaism. Later in history, many Turkic nomad peoples would convert to Nestorian Christianity, and by the 20th century all steppe nomads had converted to a religion which was not indigenous to the steppes. Almost all Turkic peoples by then had become Muslim, while the Mongols and Manchus were Tibetan Buddhists.

The history of the Khazars is an interesting case study of how nomadic empires are created and how they ultimately collapse. Through the Khazars we can better understand how nomads functioned and dispel a number of misconceptions, such as that nomads were wandering savages who were purely nomadic and would conquer a sedentary civilization simply when the urge overcome them. More broadly, understanding the Khazars is key to understanding western Eurasia during the early middle ages. The Khazar Khaganate played a crucial role in the international relations of that era. The histories of Byzantium and the Islam Caliphate during this era cannot be properly understood without knowledge of the Khazars as well.

There are very few primarily sources on the Khazars. The only documents written by the Khazars themselves that have come down to us are the Khazar Correspondence and the Schechter Letter. The Khazar Correspondence is a series of letters from the mid-10th century between the Khazar King Joseph and Hasdai ibn Shaprut, the Jewish foreign secretary of the Caliphate of Cordoba in Spain. The Schechter Letter is a letter from an anonymous Khazar in Constantinople to an unnamed Jewish dignitary. Both documents primarily address how the Khazars converted to Judaism, which will be discussed in detail in the second essay. Suffice to say for now; both documents present highly mythologized accounts of the conversion. Additionally there are several primary sources written by Byzantine, Arab, Syriac, Georgian and Armenian authors. The most noteworthy of these are Ibn Fadlan, the Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor, De Administrando Imperio by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, and History of the Caucasian Albanians by Movses Dasxuranci. Some of our knowledge on the Khazars also comes from archeological finds, mainly in the North Caucasus, Black Sea coast and in the Donbass region. It must be emphasized that due to a lack of sources, what is known about the Khazars is very limited and speculation plays a large part in the historiography.

This essay will be the first of a three part series on the history of the Khazars. The current essay is meant only to be an introduction to the Khazars and their world. It has no real overreaching argument. I thought it best to offer a broad overview of the Khazar Khaganate before diving into any historical interpretations, which of course require sufficient background knowledge to be properly understood. The second part will cover their conversion to Judaism. The essay will attempt to answer the question, why did the Khazars convert to Judaism? The third essay will look at the collapse of the Khazar Khaganate, the various theories explaining the collapse, and how the broader steppe world destabilized from the mid-9th century onwards.

The Origins of the Khazars

The precise origins of the Khazars are not entirely clear due to a lack of written sources. Nevertheless, enough information exists allowing us to make a rough outline of the ethnogenesis which made them into a distinct nomadic people. As mentioned prior, the Khazars were a nomadic Turkic people. The Turks originally entered into world history in the 6th century AD as a nomadic people living in the Altai Mountains, located between southern Siberia and western Mongolia. During this time the Turks were famed for their excellent metallurgy, especially in the production of weapons. The ethnonym “Turk” means “helmet”, and likely refers to the armor the Turks would forge, or possibly a reference to a nearby mountain that resembled a helmet. Initially the Turks were subordinate to the Rouran Khaganate, a nomadic empire that bordered China. The origins of the Turks is shrouded in myth, but what we know for certain is that Bumin of the Ashina clan lead the Turks in rebellion against the Rouran, overthrew their empire, and conquered nearly the entirety of the Eurasian steppes from Manchuria in the east to Pontic Steppes of Ukraine in the west in the process. The expansion of the Turks across the steppes was very similar to the Mongol expansion six centuries later. In fact, during their westward expansion, the Mongols collided into the Turks and intermixed with them creating a series of Turko-Mongolic peoples and states, such as the Golden Horde and the Timurid Dynasty. The Ashina clan of Bumin became in essence the royal family of the Turks. In later Turkic Khaganates the ruling Khagan had to be a descendant of the Ashina clan. This is similar to how almost all steppe nomadic rules following the Mongol conquests claimed descend from Chingis Khan in order to legitimate their rule.

As the Turks rapidly expanded westward, Khagan Bumin split the Turkic Empire and made his brother Istemi the Khagan of the Western Turkic Khaganate. At the end of the 6th century China was reunified under the Sui Dynasty, only to be replaced by the Tang Dynasty two decades later in 618. The Tang was one of China’s most powerful dynasties, and swiftly brought the Eastern and Western Khaganates under Tang dominion as vassals. With Chinese power in ascendancy the Turks fragmented. A series of revolts resulted in several independent khaganates spread across the steppes. In the east, on the steppes of modern day Mongolia, the Uyghur Khaganate emerged and in the far west, the Khazar Khaganate emerged from the wreckage of the Western Khaganate.

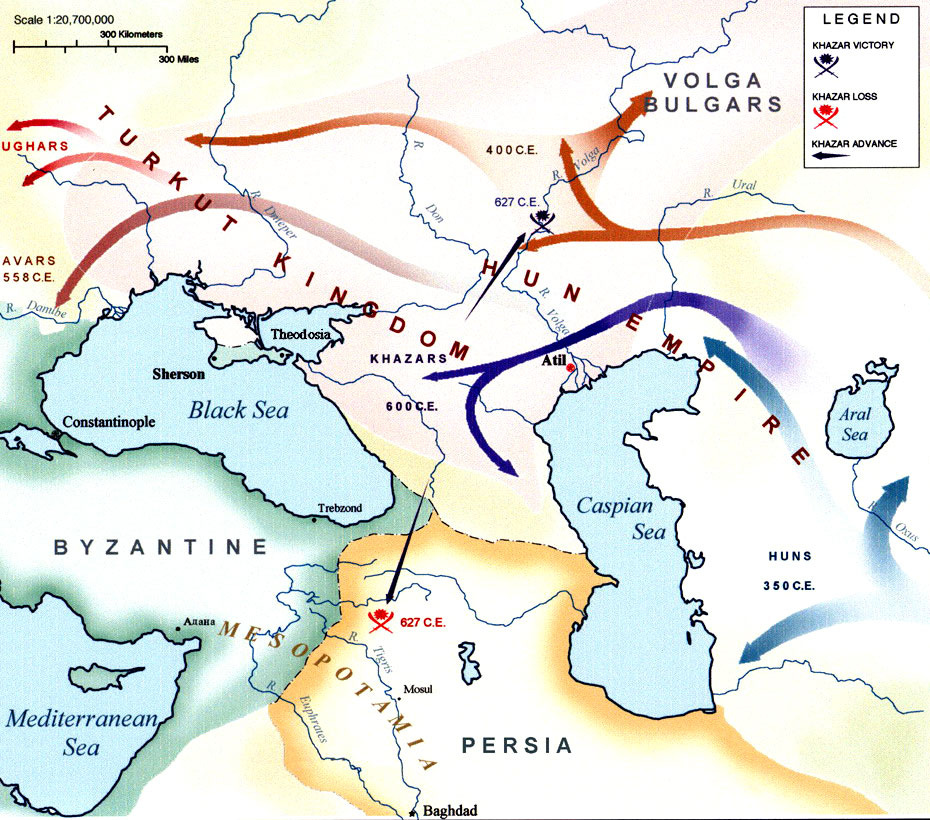

The Khazars are first mentioned in the sources during the final war between Rome and Persia. The centuries’ long rivalry between the two great empires of antiquity culminated in the early 7th century with a series of dramatic back-and-forth campaigns. First, the Persian marched west, capturing Jerusalem and the Holy Cross. They then marched further west across Anatolia, and in 626 the Sasanians reached the Asian shore of the Bosporus, just across from the Roman capital Constantinople. On the European side, the Avars in alliance with Persians besieged Constantinople on landward side. For many, it seemed this was the end for the Roman Empire.

The empire instead was saved by the Emperor Heraclius. In 627 Emperor Heraclius led a campaign deep into the Sasanian rear. Landing at Trebizond on the Black Sea coast, the Romans marched inland into the south Caucasus region, which was then the northern frontier of the Sasanian Empire. While on the march, the Emperor Heraclius sent word to the Khazars north of the Caucasus and made an alliance with them against the Sasanians. The Khazars rode south through the Caspian Gates at Darband, and met up the Roman army at the Sasanian fortress city of Tbilisi, capital of modern day Georgia. The Roman-Khazar force captured the city, and pushed southwards across Armenia into Mesopotamia. The allied force devastated the heartland of the Sasanian Empire and threatened to capture the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon near modern Baghdad. The Sasanians made peace with the Romans, returning their borders to the status quo ante. The exact political status of the Khazars is unclear at this time. They were likely still nominally subordinate to the Western Turkic Khaganate, but gained full independence in the following decades.

The question still remains, where exactly did the Khazars come from? There are a few written historical sources answering this, but they give imprecise and contradictory answers. Nevertheless, looking at the stories of their origins and using generalities from ancient Turkic history, we can make a good speculation on the precise origins of the Khazars. The sources locate the Khazar homeland to several different geographic regions. Some of the sources indicated the Khazars migrated from the southern Ural Mountains, somewhere near modern day Bashkortostan. Other sources say Attila the Huns forced the Khazars to live in the deserts south of the Volga River. Both of these possible origin stories contradict the common belief that the Khazars were a Turkic people, as the Turks came from modern Mongolia and not the Urals.

Another source offer an origin story more in line with the rise of the Turks in the 6th century. The source says, “Turks built empire and wealth from raiding Serica, and later forced the king of Seres to provide them with tribute, with tribute they gained more loyal followers. After some time Serica was eventually milked dry and the three brothers set off with 650,000 cavalry to find new lands to pillage.” To the Greeks and Romans, China was known as “Serica”, and Chinese as “Seres,” thus locating the homeland of Khazars near China which argues they were one of the tribes that migrated westward at some point during the Turkic expansion.

One apocryphal story of Alexander the Great tells of him meeting the Khazars somewhere between Merv and Herat in Margiana. This story might simply have been an attempt by a writer to link a contemporary people to the Alexander Romance stories. But it could also indicate an Iranic element to the Khazars, as the region of Margiana was inhabitant by Massagetae, a nomadic comparable to the Saka and Scythians.

The most likely answer to this mystery is that the Khazars were of Turkic tribes who intermixed with the Sabirs, a nomadic people already living in the Pontic-Caspian steppes, likely a Uralic or Hunnic people who had been subject to the Huns. It would have been politically very difficult for the Khazar Khagan to claim the title of Khagan without being from the Ashina clan, thus it is likely the Khazars were descendants from Ashina Turks that migrated west following Khagan Istemi. That being said, some debate exists whether the Khazars actually had an Ashina lineage.

Who were the Khazars?

The term “Khazar” itself requires some clarification. The word Khazar was originally the name of a specific tribe. As the Khazar tribe grew in power, bringing other tribes under their dominion and creating a tribal confederacy, the name “Khazar” originally designating a specific tribe would have become the name of supra-tribal confederacy. The early Turkic Khaganates were usually structured around a founding tribe, inner tribes and outer tribes. The inner tribes would have been the first tribes to pledge loyalty and join with the founding tribe, while the outer tribes were those who were later conquered and incorporated into the Khaganate. The Khagans would take wives from the inner tribes, and the leading men from these tribes would have held significant political and military roles within the Khaganate. For the first Khaganate there were 10 inner tribes and 30 outer ones, and while there are no sources on the internal make-up of the Khazar Khaganate in this regard, it was likely something similar. It is very likely the Sabirs were one of the inner tribes. A good comparison to explain how the name “Khazar” went from a tribal identity to an imperial one is Rome. The ethnonym of “Roman” initially referred only to the citizens of the city of Rome, but as this small group conquered first their neighbors and eventually the entire Mediterranean, the term Roman came to refer to anyone living within the empire. A similar evolution occurred with the ethnonym of “Russian”, where people like Catherine the Great or Sergei Lavrov are thought of as being Russians when they are in fact German and Armenian by blood.

Similar to the Roman and Russian Empires, the Khazar Khaganate was a highly ethnically heterogeneous entity. The ethnic composition of the Khazars themselves was likely largely Turkic, with some Uralic admixture at the very least. Similar to the Americans, the racial composition of the Khazars likely changed substantially over time. Their conversion to Judaism almost certainly resulted in marriages between Khazars and Jews with mixed offspring. All of the early Turkic Khaganates were highly cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic states. The other Khaganates in Middle and East Asia saw extensive mixing with Sogdians, Chinese, Indo-Europeans and others. Additionally, the Khazar Khagans would likely not have been all pure-blooded Turks. It is certain that the Khagans took foreign wives, as the kings of each subject people had to give a daughter to the royal harem. Turkic Khagans in the Western, Eastern, and Uyghur Khaganates all took Chinese princesses as wives and had half Turk, half Chinese children, with many becoming Khagans themselves. We can assume the Khazars were ruled by similarly mixed race Khagans.

As time went on the Khazars likely became even more so ethnically mixed. Moreover, the heterogeneity of the Khazars was likely not distributed equally across all of the inner and outer tribes. For example, the sources say the Khagan was Jewish but many lower ranking Khazars remained pagan. This likely means there was intermixing between Jews and Khazars of the founding and inner tribes, but less so with the outer tribes. This of course is not guaranteed, we lack any written sources elaborating on this, nor are there any Khazars today for genetic researchers to study. It is possible the Khazar converted to Judaism without anyone marrying Jewish people, but I find this to be unlikely. In the contemporary world, most people who covert to Judaism usually do so because they married a Jewish person. Of course, what is common today does not necessarily mean it was the case in the Middle Ages, but nevertheless I think the hypothesis that there was a large degree of mixed marriages is a fair assumption.

The Jewish conversion very likely resulted in marriages between Khazar Turks and Jews from the Middle East and Byzantium. There was also possibly intermixing with Chorasmians, people from the modern day Khiva oasis in Uzbekistan. The evidence for this is that the Khazar Khagan’s royal guard was recruited from Chorasmia. Initially the Khazars would have likely had an Asiatic appearance, similar to Mongols and Kazakhs, but this is not known for certain. There are theories of a large Iranic nomadic element to the earliest Turks, which means the Khazars could possibly have looked at least partially Caucasian, similar to Scythians. Overtime the Khazars would have racially transmogrified due to the intermixing with Uralic, Jewish, possibly Chorasmian and other peoples.

Sources also speak of “Kara Khazars” and “Aq Khazars.” The words “kara” and “aq” mean “black” and “white” in Turkic, and have both racial and status connotations. Among steppe nomads “white” was often associated with the sky, Tengri, nobility, nobleness and purity, while “black” meant commoner. The designations of the white and black likely had something to do with the existence of inner and outer tribes. The Aq Khazars were likely members of the inner tribes while Kara Khazars were subject peoples, but it still not known who exactly these people were. Additionally, Arab source say the Kara Khazars were dark in complexion, which implies there were racially different than the inner tribes.

Historical Outline

The Turks first reached the Volga River in the mid-6th century while pursing the Avars, a splinter group from the former Rouran Khaganate, the Turks former masters. The original tribe of Khazars likely arrived to the steppes north and west of the Caspian Sea near at the end of the 6th century, just a few decades prior to the final Byzantine-Sassanid War. The arrival of the Khazar tribe was preceded by the arrival of the Bulgars, another Turkic tribal grouping who lived primarily along the Kuban River. There also seems to have been many Hunnic tribes living on steppes near the Caucasus and on the steppes west of the Caspian. These Turks in the far west were likely already largely autonomous from of the Western Turkic Khaganate centered at Suyab near modern Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Without strong Khaganal control over the western steppes, conflict broke out between newly arrived Khazars and the preexisting nomads. First the Khazars subdued the Hunnic tribes closer to them, and then fought the Bulgars for dominion over the western steppes. The Khazars emerged victorious and scattered the Bulgars in several directions. Some Bulgars migrated to the lower Danube region were they overtime sedentarized, Slavicized, Christianized and would ultimately prove to be an exceptionally sharp thorn in Constantinople’s side. Other Bulgars migrated to the upper Volga, while others remained near the Kuban, both of whom became subordinate to the Khazars.

By the 620’s the Khazars were certainly already well-established on the steppes between the Black and Caspian Seas. Byzantium and the Khazars formed an alliance against Sassanid Persia which has already been discussed. In the 630’s the Khazars likely consolidated their hold over the remainder of the western steppes, fully conquering the remaining Bulgars and extending their dominion to the Dnepr River and to frontiers of Chorasmia, known today as Khorezm. In the 640’s the Muslim Arabs first penetrated north of the Caucasus Mountain, inaugurating a century and half of constant raids and warfare between the two empires. Whatever vestigial influences the Western Turkic Khaganate still on the Khazars, it was destroyed following Tang China’s conquest of the Khaganate in the 650’s. By the end of the 8th century the Arab-Khazar war had stabilized into regularized, minor raids.

In 737 the Khazars suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Arabs, with the Khazar army being encircled, the Khagan captured and forced to convert to Islam. The Arabs withdrew soon after but this defeat likely rocked the foundations of the Khaganate. Likely sometime later in the century the Khazars converted to Judaism. In conjunction with their conversion the internal political regime of the Khazars also began to evolve, namely their institution of the duel kings. The early 9th century saw the Qabar revolt, a rebellion led by disaffected Khazars for reasons unknown. The revolt failed, and the losers fled to Pannonia and the Balkans.

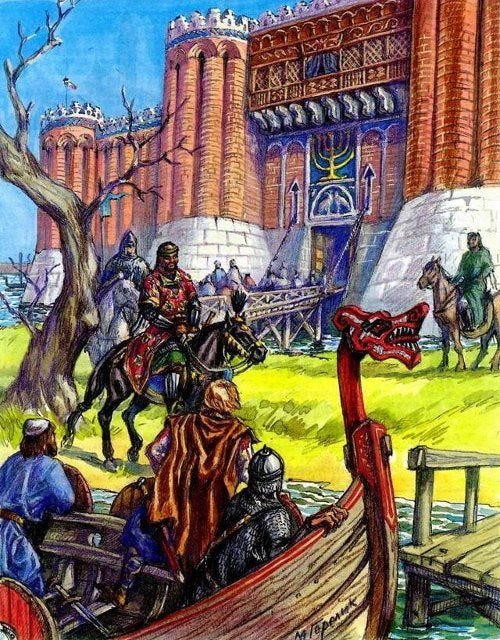

In the 910’s the first Rus and Varangian raids down the Volga into the Caspian Sea basin began, which were initially supported by the Khagan. In the 920’s the embassy of Ibn Fadlan on behalf of the Abbasid Caliphate passed through Khazaria on its way to the Volga Bulgars. Ibn Fadlan would later write one of the best primary sources we have on the Khazars, Varangians, and others. The aforementioned correspondences between the Khazar king and the foreign minister of the Caliphate of Corboda occurred in the 950’s or 960’s.

By the 10th century the inner tribes of the Khaganate were likely only partially nomadic and lived in Atil, their capital city on the Volga. Sedentarization and the immense wealth produced from international trade likely had the effect of weakening the once formidable warrior people. Like so many other great imperial peoples, the Khazars succumbed to decadence and luxury, trading the austere nomadic lifestyle which made strong for an easy life full of comforts. Coinciding with the Khazar’s decay, the Eurasian steppes destabilized from the mid-9th century onwards. First the Uyghur Khaganate collapsed in 840, and then the Tang Dynasty fell in 907. As the two principle powers that facilitated the Silk Road trade collapsed, the international commercial trading system unraveled as well. The decline of Silk Road trade negatively affected the stability of the Khaganate, and to make matters worse, a new and especially formidable nomadic people arrived to the western steppes, the Pechenegs.

The Pechenegs migrated first to the Caspian and then to the Pontic steppes and caused mass chaos in their wake, massively upsetting the harmony and peace the Khazars had created. The arrival of the Pecheneg seriously weakened the Khazars, but the killing blow ultimately came from the Rus. Led by Grand Prince Svyatoslav in 965, the Rus sacked Atil, terminating the Khaganate.

Foreign Relations

In western Eurasia the Khazar Khaganate was one of the three great powers of the early medieval world in western Eurasia, along with the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic Caliphate. It is not at all hyperbole to say the wars of these three powers determined the fate of the world.

Byzantium

The rise of the Khazars coincided with the onset of the Byzantine Dark Ages, a period of immense decline suffered by Constantinople following the Arab victory at Yarmouk in 636. Constantinople’s population was reduced to a mere 50,000, literacy become much less common and the empire’s cultural life and material prosperity were severely reduced. In fact, many historians consider this period to be where Byzantium broke from its Roman past, where “New Rome” ended and the empire become “Byzantium” as it is known today. In accordance with this periodization, it could be said that for Byzantium antiquity ended at Yarmouk and the Medieval era began.

As mentioned before, the Byzantine-Khazar alliance began in 627 with the siege of Tbilisi during the final war against Persia. As the Muslim Arabs began their extremely aggressive expansion so after, the alliance continued. Byzantium’s relationship with the Khazars remained a core pillar in Constantinople’s foreign policy during its Dark Age as the Arabs attacked the two empires relentlessly. To give an idea of the importance Byzantium placed in this relationship, all diplomatic letters to the Khazars bore a gold seal that was heavier and more imposing than the seal used for letters to the Pope in Rome. The Khaganate was likely Byzantium’s most important foreign partner.

The close relationship between Byzantium and the Khaganate is best exemplified by the extensive dynastic marriages between the imperial family in Constantinople and the Khaganate’s inner tribe. The first marriage was between Justinian II Rhinotmetus and the Khagan’s sister. In 695 Justinian II was overthrown by a mob riot. Instead of being killed outright, his nose was cut off and he was exiled to Cherson in Crimea. From there Justinian II fled to the Khazars seeking support in regaining his throne, and ultimately married the Khagan’s sister who was baptized as Theodora. Hearing of his escape from Cherson, Constantinople sent an envoy to the Khagan requesting Justinian to be returned, but before this request could be carried out Justinian was warned and fled again, this time to the fleeing court of Tervel of the Bulgars on the Danube. In 705 he marched on Constantinople with an army of Bulgars and Slavs but he could not breach the wall. After camping outside the city for 3 days Justinian entered the city with a few others by crawling through an unused aqueduct, which triggered his supporters within the city to riot and force the then reigning emperor Tiberius III to abdicate. The following year Justinian II sent a punitive mission to Cherson to punish those who had imprisoned him, but the city revolted with Khazar assistance.

The iconoclast Isaurian dynasty who ruled in Constantinople from 717 to 802 maintained a much more stable regime than Justinian II had, and intermarried with the Khazar royal house even more extensively. Constantine V, son of Leo III the Isaurian, married the Khagan’s daughter in 733 who was named Tzitzak, later baptized as Irene. Their son was Leo IV the Khazar and reigned as emperor from 775 to 780. The dynasty’s final ruler was the Empress Irene who held a more anti-Khazar policy than her predecessors, which was likely a response to Khazar support of Abkhazian independence and the campaign against the Byzantine-aligned Crimean Goths.

The era of the Isaurian dynasty coincided with the peak of the Arab threat. Leo III began his reign with the Arab siege of Constantinople in 717 and Constantine V married Tzitzak just prior to the great Arab offensive into the Caucasus, against Byzantine Abkhazia and the Khaganate itself. As the Arab threat waned in the late 8th century and the Byzantine and Khazar frontiers with the Caliphate stabilized, the alliance likely became superfluous and the relationship cooled.

The only significant sources of tension between the Khazars and Byzantium were their conflicting spheres of influence which overlapped in the northern Black Sea coast, specifically in Crimea and Akhazia. For more on the Crimea between the Khaganate and Constantinople, see the Crimea section under “Geography of the Khazar Khaganate” below in the essay. Additionally, the empires held joint claims over Abkhazia, a small kingdom on the Caucasian coast of the Black Sea. In the 770’s the Khazars encouraged the Abkhazian king Leon II to declare independence from Constantinople, but this did little to antagonize Byzantium. For more on Leon II and Abkhazia during this era see my Substack post, “Abkhazia in the early Middle Ages”.

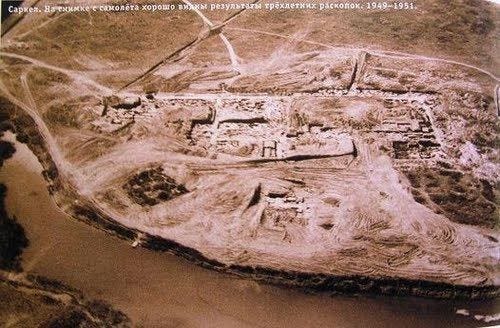

The Byzantines also built many fortresses for the Khazars, most notably Sarkel on the Don River, also known as the White House. The fortress was built in the 830s by the Byzantine general Petronas Kamateros. The primary construction material was brick. It is unknown what enemy Sarkel was meant to guard against, but historians speculate it was either the Hungarians who were beginning to migrate westwards or early Varangians coming down Russia’s rivers. Sarkel was built on the Don River where it nears the Volga River, so the fortress was likely built to protect merchants as they portaged from one river to another. It is also possible the construction of Sarkel was a result of Byzantium’s resurgence in the 9th century following the end of the Dark Age. Possibly as Byzantium experienced a new breath of life and a restored vitality trade routes were reoriented towards the empire, drawing the attention of raiding Maygars or Varangians which prompted Sarkel’s construction. The Byzantines likely also assisted in constructing the Khumara Fortress in the Caucasus.

In the mid-8th century there was an attempt by Byzantium to convert the Khazars to Christianity. Patriarch Photius of Constantinople sent his protégé Constantine to the Khazars in order to bring about the Khagan’s conversion, but he only managed to baptize a few hundred people. Interestingly, Photius was said to be “Khazar-faced”, indicating he had some steppe ancestry, or possibly even a Khazar Turk himself.

The possibility should be considered that the Khazar-Byzantine relationship might have deteriorated from 800 onwards as a result of the Khazar conversion. Even more curious, Byzantine sources do not say a word on the Khazar’s conversion to Judaism. One would think this would have been noted. I can think of two explanations for this. The first, the Khazar conversion to Judaism was highly superficial and thus deemed irrelevant by Constantinople. This is unlikely because even a superficial conversion should still have garnered at least some attention. The other possibility is that the Christian Byzantines were embarrassed their faith was not chosen by the Khazars and thus chose to downplay this failure. A Khazar conversion to Christianity would not only have been an ecclesiastical success, but it would have completely aligned the Khaganate to Constantinople. Thus the ascension of Judaism in Atil would have been seen not only as a major defeat by the church, but a defeat by the entire court and imperial apparatus. It is worth pointing out that America’s defeat in Afghanistan was totally forgotten about by the media soon after it occurred. It is hardly unprecedented for an empire to sweep its failures under the rug.

Islamic Caliphate

The main rival to the Khazar Khaganate was the Arab Islamic Caliphate. In 641 the Arabs reached the Caucasus, only 21 years after the Prophet Muhammad’s Hijrah, and in 642 they launched their first major raid north of the Caucasus Mountains where they attacked the Khazar city of Balanjar. It is possible this was when the Khazars decided to relocate their capital from Semendar at modern Makhachkala further north to Atil on the Volga. The Arabs withdrew, and in the following decades the Khazars and Huns raided the south Caucasus and attacked the Arabs there. The Arab offensive resumed in the early 8th century, with the Caliphate’s capture of Darband in 705. In 722 the Khazars launched a major raid on Armenia, which prompted the Arabs to seize Tiflis in 724. Tiflis was a major fortress city at the southern end of the Daryal Pass, and along with Darband it guarded the northern frontiers of the Caliphate. In 730 the Arabs went north through the Daryal Pass and attacked the Alans. The Khazar-Arab wars saw their climax in 737. The Arabs penetrated both the Daryal Pass and the Caspian Gates and reached as far as the Volga River where they surrounded the Khazar Khagan and his army. The Khagan was forced to convert to Islam, but he apostatized soon after as the Arabs withdrew south of the Caucasus.

In 750 the Umayyads were overthrown and replaced by the Abbasids, who sought to stabilize their imperial frontiers. For the remainder of the Khaganate’s existence back-and-forth raiding continued between the Khazars and Arabs but no campaign on the scale of the one in 737 occurred again. The 737 campaign to the Volga River would be the furthest north the Caliphate reached. The Khazars unintentionally served as the shield of Christendom and Europe against the Muslim Arabs, as without the powerful Khaganate to resist the Arab advance northwards it is fully possible armies of the Caliphate could have conquered the Rus and beyond. In this sense the Khazars are very comparable to Byzantium and the Franks in the west. Just as Leo III stopped the Arabs at Constantinople in 717-718 and Charles Martel stopped the Arab advance into Western Europe at Tours in 732, the Khazars prevented an Arab penetration into Eastern Europe.

Varangians and Rus

The era of the Khazars also coincided with the expansion of the Vikings, also known in the east as the Varangians, as well as the later formation of ancient Rus. It was during this era that the eastern Slavic tribes underwent an ethnogenetic process which would result in the emergence of Kievan Rus, the progenitor of modern Russian, Ukraine and Belarus.

The various Slavic tribes were either subject peoples under the Khazars and obligated to pay an annual tax in pelts, or victims of regular slave raiding. The city of Kiev was likely founded by the Khazars as a trading post where merchants of the Khaganate could collect furs and slaves. Whereas the Slavs were largely either vassals of the Khazars or victims of slave raiding, the Varangians would have been trade partners and mercenaries. It is likely that many of the Slavic slaves sold in Khazar markets were initially captured by the Varangians and sold to the Khazars later. More broadly, the Varangians served to integrate the far north into the Silk Road. They would have sold amber and furs to the Khazars in addition to slaves.

This early period is not well understood, but what is known is that the Varangians from Scandinavia made their way from the Baltic Sea to the interior of the continent and came to rule over the Slavic tribes on the Dnepr River. It also appears the political regime of the early Kievan Rus greatly resembled the internal political arrangements of the Khaganate. According to sources there was a duel kingship system with a sacred figurehead king and another king with real authority. It even appears at one point a “Rus Khaganate” existed, implying the existence of the Rus Khagan. Yet, extremely little is known about any of this.

Later in the 10th century the Rus conducted two major raids in the Caspian Sea basin.The first raid was in 913 and the second in 943. In the first raid, the Rus made an agreement with the Khaganate to provide the Khagan with half of all goods they looted in exchange for being allowed to sail down the Volga past Atil. For reasons not understood there was a falling out between the Khazars and the Rus upon their return, with the Khazars attacking and killing the entire Rus host. The second raid ended even more anticlimactically, with the Rus all dying in Barda, in modern Azerbaijan, due to dysentery.

The Khazar Khaganate was ultimately destroyed by Kievan Rus in 965, when the Grand Prince Svyatoslav sacked Atil. Afterwards the Rus attempted to claim the Khazar’s legacy in western Eurasia for themselves, hoping to inherit the Khazar’s tributary empire but this did not pan out.

Dual Kingship System

Along their conversion to Judaism, the other particularity about the Khazars which has drawn attention to them is their unique political system of dual kings. The Khazar Khaganate was not ruled solely by the Khagan like in other Turkic steppe empires, but shared his authority as sovereign with the “Bek”. The title of Khagan is similar to the later title of Khan, both being equivalent titles of emperor, whereas Bek is comparable to the title of lord. Nominally the Bek was the second highest office in the Khaganate, subordinate only to the Khagan, while in reality the Bek was the primary ruler of day to day affairs. The Khazar Bek would lead the army in the field, manage state affairs and meet with foreign envoys. Real power lay with the Bek, while the Great Khagan by contrast was merely a figure head. It is generally agreed upon that initially the Khagan and Bek ruled as equals, or at least shared power, but overtime the Bek appears to have completely sidelined the Khagan to a purely ceremonial role. While this is known, it is debated when this change occurred and why.

It must be noted that the Khazars did not view the Khagan as a purely ceremonial position. In fact they did truly regard him as the highest person in the state, just not for earthly political reasons. Instead they thought to be the Khagan to be the source of “qut”, a spiritual charisma that would emanate out from the Khagan and bless the entire realm. For the sake of simplicity it is best to think of qut as what we would regard today as “good luck”. The Khagan was essentially a good luck totem embodied in human form. This notion of qut and good luck was not solely a Khazar belief. All Turks of this era believed in this idea, the only difference was that they believed qut emanated from Mount Otuken, likely located in the Altai Mountains. The Turks in the eastern and central steppes would do annual pilgrimages to Otuken for worship and believed this scared mountain was where they originated from as a people. The mountain was thought to be a nexus between heaven and earth, where qut would enter into the human world. It is likely the Khazars being so far from the Altai Mountains simply transferred the role of Mount Outken to the figure of the Khagan. Instead of Otuken being the nexus from where qut would enter the human world, the Khagan was the nexus point. As a result the Khazar Khagan was considered to be a sacred person.

The Khagan would have come from the founding or inner tribes, likely an Ashina Turk, and was selected by the leading men in an election. During the crowning ceremony the leading men of the Khaganate would carry the new Khagan up high on a carpet or shield facing the sun and spin him nine times, and upon each turn his subjects would bow. After this, they help the Khagan mount a horse, and while on the horseback the leading men would strangle the new Khagan with a silk scarf until he neared death. As death approached, the new Khagan would be asked, “How long will you be Khagan?” The Khagan would answer with a number, and that number would be the number of years the Khagan would serve in that role. The belief was that in a state of near death, the new Khagan would lose contact with this world and enter the spirit realm. In the spirit realm his mind and soul would be clear, allowing him to give the “correct” answer. The ceremony was called the “Ascent to Heaven”.

It was believed that once however many years he had stated were over, the Khagan would no longer be a source of qut, and would be ritually strangled to death with a piece of silk. Additionally, if there is a famine or a military disaster, the leading men of the Khaganate would go the King and say he brought them bad luck. Believing him to no longer be a source of qut they would kill him in a similar manner as if he had completed is term.

The Khagan served as the sacred totem of the Khazar state. The Khagan lived in the capital city of Atil in a palace on an island on the Volga River. In order to visit the Khagan, a person had to pass through purifying fires before they can see the Khagan, which was a common ritual among steppe nomads. The palace was a large structure made of mud bricks, where the Khagan lived with his harem of 25 wives and innumerable concubines. Every ruler of a vassal kingdom under the Khazars had to send a daughter to the Khagan to be his wife. Each wife and concubine had her own room in the palace and a eunuch slave who protected her. The Khagan’s harem was kept entirely secluded from the outside world, with their eunuchs ensuring no one but the Khagan laid their eyes on them.

The Khagan was rarely seen outside of his quarters. Only 4 times a year did he venture beyond the palace according to some sources, likely for seasonal holidays. Anyone who encounters the Khagan while he traveled outside of his palace and court had to prostrate before him. Wherever the Khagan went a large metallic disc was held up behind him, which would reflect the sun’s rays symbolizing the Khagan as the sun, and as the center of the army and state. At court the Khagan was often veiled. According to Ibn Fadlan, the burial site of a former Khagan consisted of a underground tomb with 20 room where the Khagan would be buried with servants, horses and weapons so he could conquer the next world. Afterwards a river was diverted as to flood the land above the tomb in order to prevent any grave robbers for desecrating the site. Additionally, everyone involved with the burial would be executed so nobody would know where exactly the tomb actually was.

While the general details of the dual kingship system are known, what is unknown is how this institution evolved over time. Some speculate the dual kingship system only emerged following the catastrophic defeat in 737 as the position of Khagan was thoroughly discredited. In accordance with this theory others argue the dual kingship institution was either a Jewish innovation or somehow a product of the Khazar’s conversion. Others believe the dual kingship system existed prior to the Jewish conversion. Some argue the dual monarchy was created to give the conquered Bulgars a role in the Khaganate, as a method of reconciliation. Others argue it was introduced to the Khazars by the Chorasmians who began fleeing the Khaganate due to the Arab invasion beginning in 712. There is also a large grouping of historians who believe this institution to have originated among Iranic nomads who were subordinate to the Khazars, and somehow transferred their political arrangements to their conquerors. Some historians who believe the institution came from a non-Jewish origin believe that the Khazar state was ruled by duopoly monarchy prior to the Jewish conversion, with the Khagan and Bek sharing power. In accordance with this line of thinking, the conversion to Judaism in fact created a de facto unifed monarchy, as they believe Jewish influence was the driving force in sidelining the Khagan and raising the Bek to be the primary head of government.

What I have outlined here is a very basic overview of historiography covering the Khazar dual kingship system. Many of these theories rely on very arcane arguments related to etymology of words and vague similarities to other nomadic peoples that existed historically or contemporary. For purposes of brevity and simplicity I have decided not to dive too deeply here, but for anyone interested, I recommend “Khazaria in the 9th and 10th centuries” by Boris Zhivkov. Moreover, this political arrangement is not totally unheard of. The Spartans had a similar system of dual kings and the British today have a ceremonial monarchy and office of Prime Minister. Nevertheless, this dual kingship system is quite the oddity and remains ill understood by historians.

Khazar Army

The role of general under the Khazars was called “Spasalar”. Along with tribal levies, the Khazar army was also made up of the “al-Larisiya”, who served as royal bodyguards and as elite forces. The al-Larisiya came from Chorasmia, possibly as refugees from the Arab invasions, although it is said in the sources that the al-Larisiya were Muslims. The “Cavus” or “Javsigr” was the army commander, who was responsible for organizing the army, managing the Khagan’s escort, and marshaling the ranks for battle. This role would be equivalent to a staff officer in modern militaries. Under Khazar law retreating from battle was strictly forbidden. Anyone that retreated was killed, and if it was a commander that fled he would be forced to watch his wives and children being given away as slaves and he himself would he crucified.

Law and Punishments

While the state was officially Jewish, the population of the Khaganate was highly mixed with many Christians, Muslims and Pagans. As each religion had its own laws and regulations on personal behavior, the Khazars sought to maintain harmony among its people by creating a legal system akin to the Ottoman millet system. Jews, Muslims, Christians and Pagans were all under separate legal jurisdictions according to their faith, which meant those accused of crimes would be judged by people of the religion. In Atil there were seven high judges, and of them two Muslims, two Jews, two Christians, and one Pagan.

The standard form of execution under the Khazars was to be tied to two or four horses and then pulled apart. Adultery was punished by the guilty being tied to the ground and then cut in half from the neck to the groin with an ax. They would then hang the sides of the two guilty parties from a tree. Nobles were never executed; instead the Khagan would command them to commit suicide, indicating a strong honor culture among the elite, which is standard for warrior peoples.

Economy

The internal economy of the Khazars was based on a mix of traditional nomadic pastoralism and agriculture which supported the Khaganate’s urban centers. The Khaganate was likely largely autarkic due to access to grazing and farm land, high availability of cheap slave labor, as well as control over urban centers where manufacturing would occur. Yet, autarky merely results in self-sufficiency and not in great wealth which all men desire.

The Khazar Khaganate derived much of its wealth from the “Silk Road” international trade. Khazar trade was largely conducted along the internal navigable waterways of the Khaganate, with the Volga River linking the Khazars to the Persia and the Caliphate, while the Don and Dnepr led to Byzantium. Trade routes also connected to Chorasmia in the east and to Germany in the west. It is worth noting the Khazar Khaganate emerged coinciding with the reunification of China under the Tang Dynasty. Beginning in the 640’s Tang China expanded deep into Central Eurasia, with Tang armies conquering the Turks on the steppe and reached as far as Sogdia in the west. It was Tang hegemony that created Silk Road, and it was during the Tang epoch that Silk Road trade was at its greatest volumes prior to the Mongol conquests. Just as the prosperity of the Khazar Khaganate was dependent upon the Silk Road which Tang China inaugurated, the history of the Khazar Khaganate can only be understood in a broader Eurasian context.

The Khazar’s international trade routes were likely based upon connections between Jewish merchants in the Khaganate and the diaspora living in Central Europe, Byzantium, and the Radhanite Jews in the Caliphate and elsewhere in Central Asia. Additionally it is worth noting the Khazar epoch coincided with expansion of Nordic and Varangian commercial activity across modern day Russia. The Khazars would have been able to tax all trade transiting the Khaganate from Scandinavia to the south.

The main sources of wealth for the Khazars were highly valuable exports such as slaves and furs. The Khazars mainly enslaved Slavs, but also likely sold captured Turks from rival tribes as slaves as well. The Khazars seemed to have preferred to raid the Slavs during the winter for slaves. The exact scale of this slave trade is unknown due to a lack of sources, but rough estimates can be made. Long after the Khazars had disappeared, the Slavs of what would become Russia continued to be subjected to slave raiding by Turkic nomads to their south. In the first half of the 17th century alone, an estimated 150,000 - 200,000 Russians were captured primarily by the Crimean Khanate to be sold as slaves to the Ottoman Empire. This trade was also comparable to the slave trade handled by Arabs in Central Asia and later by the Samanid Emirate, an Islamic state based out Sogdia which existed in the 9th and 10th centuries. Under the Arabs and Samanids, Turks captured during inter-tribal warfare were sold in Sogdian markets to buyers from Persia and Khorasan. The main routes of the slave trade were to Chorasmia and then to the Caliphate, and to Tmutarakan on the Taman Peninsula, where slaves would then be taken to Byzantium.

Animal furs were also a very important export commodity. The Khazars largely sourced furs from subject peoples to their north, who would have given the furs they captured to the Khazars as either a form of tribute and tax, or through a commercial transaction and trade. The economic life of these people was largely based on the fur trade, with some tribes such as the Volga Bulgars even using squirrel furs as a form of currency. Their animal traps were designed not to damage the skin, and they used blunt tipped arrows which would kill but not pierce and damage the pelt. The most common furs exported were sable, grey squirrel, ermine, fox, marten, beaver, and spotted hare. The Khazar’s involvement in the fur trade was very comparable to the later Russian Empire’s involvement in the trade, both whom expanded into the far north of Eurasia for the purpose of securing additional furs to be sold to wealthy foreign markets. Both furs and slaves were primarily sold into lands under the rule of the Islamic Caliphate, causing a major out flow of silver from Islamic world to the Khazars and to peoples further north including the Scandinavians.

The main imports to the Khaganate were finely crafted manufactured goods that the Khazars lacked the ability to produce. Naturally, manufacturing and craftsmanship requires an urbanized workforce which the Khazars, at least initially, did not have for reasons already explained. From Persia the Khazars imported swords with no furnishing which they add later themselves. From Byzantium the Khazars purchased weapons, plates, cups, silver dishware, textiles, carpets, wine, amphora, and luxury goods.

To give the reader an idea of how commerce was conducted in this part of the world at this time, it is worth quoting the Arab traveler Ibn Battuta wrote an account of how trade worked with the Slavs in the far north. “When the travellers have journeyed for forty days, they make camp near the Land of Darkness. Each of them puts down the merchandise he has brought, then retires to the campground. The next day they return to examine their merchandise and find set down beside it sable, squirrel and ermine pelts. If the owner of the merchandise is satisfied with what has been placed beside his goods, he takes it. If not, he leaves it. The inhabitants of the Land of Darkness might add to the number of pelts they have left, but often take them back, leaving the goods the foreign merchants have displayed. This is how they carry out commercial exchanges. The men who go to this place do not know if those who sell and buy are men or Jinn, for they never glimpse anyone.”

Geography of the Khazar Khaganate

From Kiev in the west to the Aral Sea in the east, the Ural Mountains in the north and the Caucasus in the south, the Khazars established their hegemony across the entire western third of the Eurasian steppe lands. The Khaganate covered the entirety of southern Russia, much of central Russia, the eastern half of Ukraine and western Kazakhstan. Subordinated the Khazar Khaganate, there were peoples who lived under radically different conditions in terms of socio-political organization and economy. There were semi-nomadic fur trappers and pastoralist in the far north and in the North Caucasus; sedentary kingdoms and urban settlements in the Crimea, Donbass, and Caucasus; and various nomadic peoples scattered throughout the steppe.

Volga River Basin

The Khazar Khaganate was centered on the Volga River, then called the Atil River after Attila the Hun. The Khazars dominated the Volga’s drainage basin both politically and economically. The Volga served as a major transport artery allowing for quick and convenient travel from what is today the Moscow region in the north to the steppes and Caspian Sea basin in the south. The Khazars also controlled the Kama River which begins near the Ural Mountains and feeds in the Volga near modern day Kazan. The upper Volga and Kama rivers were home to various Turkic, Uralic and Slavic peoples. Khazar merchants would have been able to easily travel up and down the Volga River, integrating the entire basin’s population into the Pax Khazarica commercial network.

The Volga Bulgars were a Turkic, semi-nomadic people who had lived in the western Eurasia prior to the arrival the Khazars, but were conquered by the Khazars and were made into tributary vassals. The Volga Bulgars lived around the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers had to pay an annual tax of one sable skin per household to the Khazar Khagan. Reportedly, the Volga Bulgars had one city name Suvar which functioned primarily as a trade center. It was said to be a “grim and forbidding place”. There were several additional peoples subordinate to Bulgars such as the Uralic Ves and Aru tribes who lived further north. They primarily trapped beaver, grey squirrel and ermine and had to pay annual taxes in fur to the Bulgar King, who in turn paid a fraction this revenue to the Khagan. The Pechenegs were another Turkic nomadic tribal coalition who arrived to the southern Ural and later Pontic steppes in the 9th century, and they also paid taxes in the form of animal furs, as well as beeswax and hides. Additional peoples subordinate to the Khazars in the Volga basin were the Ungaroi, later known as the Maygars and todays as Hungarians, the Burtas, likely another Uralic or Turkic tribe who lived in modern day Bashkortostan, and the Slavs who have already been discussed.

Atil & Samander

The capital of the Khazar Khaganate for most of its history was the city of Atil on the lower Volga River. The capital was initially located at Samander in Dagestan, but due Arab invasion the capital was relocated further north to where it was more secure.

Samander was originally constructed by Persian Sassanid Shah Khosraw Anushirvan in the 6th century as a part of the Sassanid fornications guarding the Caspian Gates and the Derbent pass. There is ongoing historical debate on the exact location of Samander. Some believe it was located between the Terek and Sunzha Rivers in the northern Dagestani plain, but most evidence indicates it was located very near to modern day Makhachkala, capital of Dagestan, Russia. More specifically, Semander was likely on top of the Tarki Hill which overlooks the city of Makhachkala. The modern city largely lies between Tarki and the Caspian Sea. The Tarki Hill towers 500 meters above the lowland plain below. Samander lies at the northern end of the lowland Caspian corridor which runs north-south between the Caucasus Mountains and Caspian Sea. At Samander/Makhachkala the lowland corridor dramatically narrows to a mere 5 kilometers between the sea and the Tarki Hill, making it a natural strong point. There was likely a fortress and palace on the Tarki Hill with city’s inhabitants living on the plain below.

Samander reportedly had many gardens, orchards and as many as 4000 vineyards. Buildings were almost entirely made of wood, which explains a complete lack of ruins. Semander remained under the Khazars for the entirety of their history, but they lost control of Derbent further south repeatedly. In the 8th century the Arab Muslims captured the city several times. Later in the 9th century it was captured by Sarir, a Christian kingdom in the mountains of Dagestan with its capital at modern Khunzakh. Later in the century Derbent was captured by Shirvan (modern Azerbaijan), who limited Khazar commercial access through the Caspian Gates trade, forcing Khazar merchants to redirect their trade to Chorasmia in the east.

The Khazars likely relocated their capital to Atil following the Arab raids in 642 or after their defeat in 737. Later in the 18th century Tarki was the capital of the Shamkhalate of Tarku, a small Kumyk state had been a vassal of the Golden Horde prior to its destruction and was likewise highly dependent on the trade of Slavic slaves to Persia in the south. For more on the Caspian Gates and the Khazar-Arab Wars read my first Substack article, “The Caspian Gates”. Atil was likely located near the delta of the Volga River near modern day Astrakhan. Atil was the main urban settlement in the Khaganate, home to the Khagan and the Khaganate’s administrative apparatus, along with housing for merchants, artisans and others. The peace created by Pax Khazarica made agriculture in the steppe lands feasible. Farmers were protected by the Khazar state which allowed Atil to sustain a large urban population. According to what archeological evidence that does exist, farms and vineyards were not located near the city of Atil but further upstream. The river’s delta would have been rich in fish and irrigation canals were dug which were used for fish farming.

The city itself spanned both banks of the Volga River. The left bank of the river (eastern bank as the river flows south) was home to the homes of the all the leading men of the Khaganate, presumably the warrior elite, wealthy merchants, religious officials and high ranking state officials. The right bank of the river was home to the city’s commoners. According to Ibn Fadlan, the city’s Muslim population was cosigned entirely to the right bank of the river. They were all under the khaz, who was responsible for all their civic affairs from legal judgments to tax collection. Only the Khagan and the Khaganate’s leading men were allowed to live in clay houses, the rest the population lived in either tents or houses made of wood and reeds.

North Caucasus – Huns, Sarir, Durdzuks, Alans and Kasogs

The North Caucasus was one of the most varied regions in the Khaganate, home to a wide range of peoples including Huns who did not follow Attila into Europe, the Alans, the Kingdom of Sarir, Kasogs, Bulgars, various mountain tribes and scattered urban settlements.

The Caspian plain in the north of modern Dagestan was mostly under the control of the Jidan Kingdom made up of Caucasian Huns who were likely only semi-nomadic. Somewhere here was the capital of the Caucasian Huns known as Varachan. Its exact location is unknown. In the eastern half of the North Caucasus lowlands are the Terek and Sunzha Rivers, both of which originate in the high Caucasus and flow eastward across the steppes and foothills before feeding into the Caspian Sea. Along these two river valleys were numerous small urban settlements that likely functioned primarily as markets and centers of exchange between nomads living on the steppe and highlanders in the mountains, those who lived in the modern regions of Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia. The city of the Balajar was likely the largest settlement here, located between the Terek and Sunzha near the Caspian coast, in the vicinity of modern Kizlyar. The city was likely named after a local Hunnic tribe called “Zhar”.

Archeologists have uncovered remains of the Andrei-Aul Hillfort, located near Endrei in Dagestan, just south of Khasavyurt. In the 18th century Endrei was subordinate under the aforementioned Shamkhalate of Tarki and hosted a large slave market. It is impossible to know what the economic life of the hill fort and the surrounding region consisted of during the Khazar era. Yet, considering how the Khazar economy was based on the slave trade similar to the later Golden Horde and Shamkhalate, it is fair to speculate that slavery likewise was the main economic activity of the region.

In the mountains of Dagestan there was the Kingdom of Sarir with its capital at modern Khunzakh. Sarir was a small, highly fragmented Christian kingdom that was subordinate to the Khazars for the majority of the Khaganate’s existence. Sarir was converted to Christianity by missionaries from Iberia, modern day central and eastern Georgia, and by Caucasian Albania, modern Azerbaijan. Sometime in the late 8th century the Arabs likely penetrated into the Dagestani mountains and forced the king of Sarir to convert to Islam, but soon after, a Khazar army intervened and helped restore Sarir to Christianity. Later in the 9th century Sarir temporarily occupied Derbent, indicating Sarir had broken away from Khazar dominion sometime earlier.

Known as the Durdzuks by the medieval Georgians, the Nakh peoples living in modern day Chechnya and Ingushetia, would also have been highly independent of the Khazars. There is almost no recorded information on what existed amongst the Durdzuks during the Khazar era, but some speculations can be made based on what is known of the Nakh peoples prior to their conquest by Russia. Prior the Russian conquest and Imam Shamil’s short-lived Caucasian Imamate there was no state to speak of. Instead what existed were purely patrimonial relationships amongst clans and an honor based culture, comparable to what existed amongst steppe nomads when there was no centralized state. The Nakh peoples would have been highly politically fragmented unlike the Alans, even more so than Sarir.

Not only mountainous, in both Chechnya and Ingushetia the lowland regions were highly forested as well up until the Russian conquest. These thick forests caused immense grief to Russians in the 19th century as they provided shelter to highlanders resisting Russian imperial rule. Russia was only able to conquer modern Chechnya and Ingushetia after cutting down large swaths of forest. Presumably these thick, gloomy forests that had existed prior to the Russia’s conquest also existed during the time of the Khazars. Such dense forest make cavalry maneuvers impossible and would have entirely negated the Khazar’s cavalry based army.

Further west were the Alans who lived in the modern day Russian regions of Ingushetia, North Ossetia-Alania, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia. The Alan capital was called Magas. Its location is disputed by historians; some believe it to be at the same place as modern Magas, capital of Ingushetia, other think it was at Arkhyz, a village in the upper Bolshoy Zelenchuk River valley in Karachay-Balkaria. The Alans were an Iranic nomadic people who migrated westwards from Central Asia to the Pontic steppes and Kuban region sometime around the 1st century AD. Several centuries later when the Huns migrated westwards they dislocated the Alans, pushing some tribes into Europe who eventually settled as far as Spain and France, while others migrated south towards the Caucasus. The Khazars pushed the Alans further into the Caucasian Mountains, which likely resulted in them becoming only semi-nomadic. The Caucasian Alans lived in river valleys of the Terek, Zelenchuk, Laba, and in the region of Pyatigorsk and Mineralnye Vody. According to sources they built stone castles at the entrances of valleys leading into the mountains and several stone forts in the lowlands. When threatened, the Alans would move their flocks and people into these fortified settlements for safety. As indicated by their castles, the Alans were likely only partially nomadic and subsisted on pastoral farming. Alans were vassals of the Khazars throughout the most of the Khaganate’s history, but it appears they became largely independent in the 10th century and looked more to Constantinople than they did to Atil.

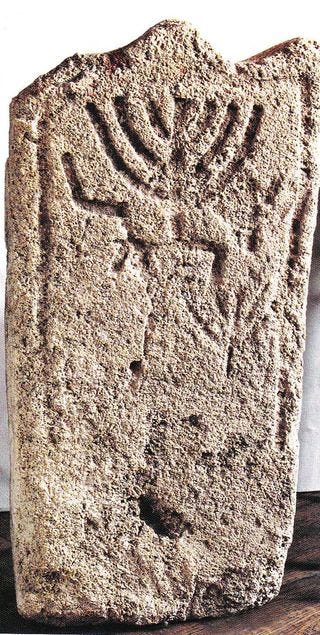

The Alans were a particularly important people for the Khazars, as they controlled the two of the three main routes leading south over the Caucasus Mountains. They guarded not only the Daryal Pass which runs from modern Vladikavkaz in Russia to Tbilisi in Georgia, but also several smaller and more difficult mountain passes further west along the main mountain range of the Caucasus, all located at the upper reaches of the Kuban’s tributaries. These passes lead to Svaneti and Abkhazia, and largely saw commercial traffic. Known as the Misimian Branch of the Silk Road, these passes linked trade routes running across the Eurasian steppes to Abkhazian ports on the Black Sea. From these port merchants could sail to and from the Byzantine Empire. These trade routes were the most active in the 6th century AD during the reign of Justinian. Yet these passes did see the occasionally invasion, such as in 737 when the Arabs went up the Kodori River valley after first attacking Abkhazia. In response, the Khazars built the Khumara fortress in the lower Teberda Valley. Within the Khumara fortress, Jewish graves and the ruins of a tabernacle shaped structure have been found. For more on these trade routes linking the Khazars and Alans to Abkhazia and Byzantium, and the Khumara fortress among other fortress in the regions, see my other Substack, “Abkhazia during the Early Middle Ages”.

The importance of the Daryal Pass was largely military-strategic as just to the south lay Kartli (ancient Iberia, modern day central Georgia) which was under Islamic occupation. Repeatedly throughout the wars between the Khazars and the Caliphate, Arab armies rode north through the Dayral Pass to attack the Alans and Khazars. The Arab invasions into the North Caucasus had a very destabilizing effect. The steppelands of modern day northern Dagestan were largely agricultural and were dependent upon a high degree of security provided by Pax Khazarica, otherwise their crops would be trampled, their homes destroyed and possibly they would be taken away and enslaved. The repeated Arab invasions in the 8th century which penetrated north of the Caucasus forced many farmers and Alans to flee to the Donbass region and upper Seversky Donets River.

Additional peoples who lived under the Khazar hegemony were the Kasogs, who were likely ancestors of the Circassians, Bulgars on the Kuban River Valley and various peoples living deep within the Caucasus Mountains. The Kuban Bulgars were likely largely nomadic and under full Khazar control. The Kasogs and Caucasian highlanders were likely the exact opposite, highly independent and largely beyond the Khazar’s reach. These peoples lived in environments that were perfectly suited for resisting external control and had fierce warrior cultures. The part of the Black Sea coastline between Abkhazia and the mouth of the Kuban River was where the Kasogs lived, and was known to the Byzantines as being extremely dangerous. Later in the 19th century Russia only gained full control of Circassia after ethnically cleansing the majority of the population and forcing them to flee to the Ottoman Empire.

Crimea

Crimea was split between the Khazar Khaganate and the Byzantium, who had overlapping layers of sovereignty over some parts of the peninsula. The majority of the peninsula is a continuation of the Eurasian steppe, with the Tauric Mountains in the south sheltering a narrow lowland coast. Dating back to the 8th century BC Greek colonies had existed on the peninsula, and they remained largely Greek in the era of the Khazars.

The northern steppelands of the Crimea were likely wholly occupied by nomads, by Turkic and Iranic tribes. In previous waves of nomadic migrations emanating out of Asia, many tribes who had lived on the Pontic Steppes were displaced to Crimea by the newcomers. For example, when the Scythians arrived to the Pontic steppes they displaced the Cimmerians who migrated into Crimea, and the Scythian themselves settled in Crimea when they were displaced by the Samartians later. Considering the relatively small pasture lands on the peninsula and the Khazar’s control over the more distant cities beyond the Tauric Mountains, the nomads on Crimean steppes were likely fully subordinate to the Atil.

The Khazars had the weakest control over the Tauric Mountains, which were largely settled by Goths who migrated there during the 4th century. The Goths were largely pagan with some having converted to Christianity. They lived in fortified hilltop settlements such as Chufut-Kale and Mangup, known to the Byzantines as Doros. The Goths were able to maintain their autonomy from the Khazars thanks to their relationship with Constantinople. Under the reign of Justinian many Greek and Gothic settlements on Crimea were heavily fortified, and later into the Khazar era this relationship between New Rome and the Crimean Goths continued. Despite the Byzantine-Khazar alliance the Byzantines nevertheless promoted anti-Khazar movements amongst the Goths.

In 786 the Khazars attacked Doros, and forced the Goths into submission. A Gothic Christian priest named John of Gothia led an uprising which drove out the Khazar tudun from Mangup. The Christian Goths held Mangup for a year before the Khazars retook the city. It is uncertain to what degree of support this uprising had, but ultimately John of Gothia would flee to Amastris in Anatolia. The primary sources say little about Byzantine support for this revolt, but it can be speculated that Byzantium hoped to see a buffer exist between the Greek cities on the southern coast of Crimea and the Khazars further north. Additionally there were surely elements within the church who wanted to see Christianity ascendant among the Goths. It must also be considered that the support for John of Gothia’s action might not have come from Constantinople but instead was the work of local actors in Cherson and Parthenit operating independent from the central imperial organs.

The Greek cities around the southern perimeter of Crimea appear to have been under some form of duel control by Byzantium and the Khaganate. The cities of Cherson, Pathenit, Sugdea, Theodosia and others remained under Constantinople’s political control but hosted a tudun from the Khaganate who collected taxes on behalf of the Khagan. The exact nature of this duel sovereignty is unknown. Seemingly there was not a uniform control over the peninsula’s Greek cities by either empire; instead their relative authority would sway back and forth depending on local political and commercial concerns unique to each city, and Constantinople’s relative influence compared to the Khaganate’s.

For much of the 8th and early 9th century Cherson, the largest Greek city on the peninsula, was under the Khaganate’s control. In the 9th century Byzantium emerged from its post-Hieromyax dark age and began reasserting itself across all of its frontiers. Constantinople regained political control of Cherson and established the Cherson Theme (a Theme was a military-administrative territorial subdivision akin to province or state. In the 7th century the Theme system replaced the old Roman provinces, and was meant to strengthen the empire’s territorial defense in the face of the innumerable threats on all of its frontiers). Throughout the Khazar epoch Cherson served as the main diplomatic nexus between Constantinople and Atil. Notably, the first Strategos (military governor) of the Cherson Theme was the leading architect who built the Sarkel fortress for the Khazars on the Don River. Yet despite a restoration of Byzantine rule, the Khazars retained a strong degree of commercial and financial control over Cherson.