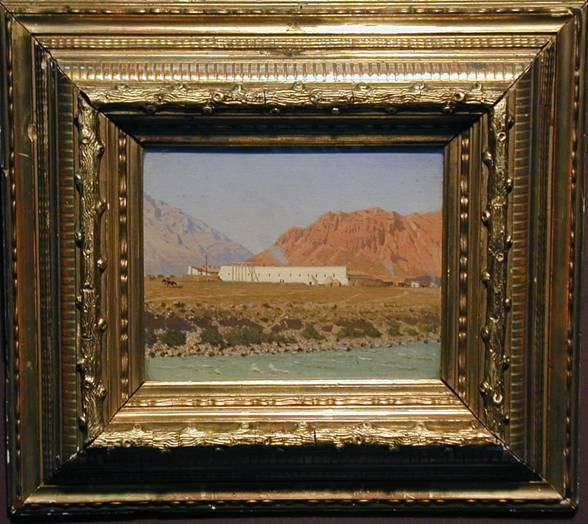

The Naryn Fortification - Nikolai Zeland, 1888 & A. Sokolov, 1908

Translations of two reports on Russia's most remote outpost in the Tianshan Mountains

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below are translations from two separate travelogues, both describing the Russian Empire’s small outpost at Naryn in the Tianshan Mountain, in modern day Kyrgyzstan.

The first is by Nikolai Lvovich Zeland, from his “Кашгария и перевалы Тянь-Шаня. Путевые записки” (Kashgariya and the Passes of the Tianshan. Travel Notes), published by the Western-Siberian Department of the Russian Imperial Geographic Society, Book IX, 1888. The original text can be found here. The source for this translation can be found here. Zeland was a graduate from the Military Medical Academy of Saint Petersburg, and worked in modern day Kazakhstan. He wrote about local medical affairs and anthropological texts on the Kazakhs.

The second is by A. D. Sokolov, from his “Тогуз-Торау. (По новой дороге из Семиречья в Фергану.), Верный, 1908.” (Toguz-Torau (Along the New Road from Semireche to Fergana), 1908) Verny, 1908. Unfortunately, I can find nothing about this author, including his full name, who he was, or an original version of the text. The source for this translation can be found here.

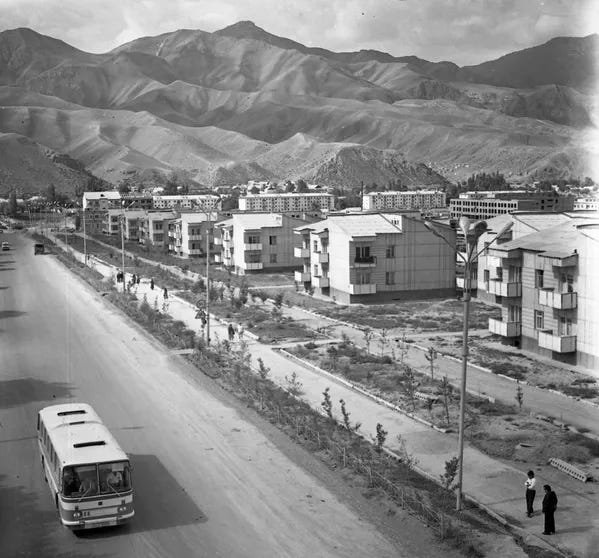

The focus of these two excerpts is the Russian fortification at Naryn. Located deep in the arid heights of the Tianshan Mountains, Naryn would have been one of Russia’s most distant and remote outposts. It had a special significance as it controlled one of the main roads from Kashgar. Thus it would have had both a military and commercial importance to Russia. The Kashgar-Torugart Pass-Naryn route was historically one of the main caravan roads on the Silk Road, and one of the two routes leading from Kashgar to the Fergana Valley (the other being the Irkeshtam Pass). Due to communism and the sealing of the Soviet Union’s and China’s Central Asian border, these regions became isolated backwaters in the 20th century. But with the revitalizing of trans-Eurasian trade due to China’s New Silk Road initiative, these routes are again being used by traders. Today, bazars in Kyrgyzstan are full of Chinese goods. Personally, seeing Chinese shipping containers scattered along the sides of roads in Kyrgyzstan was very representative of the new Silk Road that is being recreated.

Russian settlements such as Naryn were also very important from the standpoint of the local economy. Russian colonialism was often quite beneficial for nomadic peoples, as the Russians occupied a complementary economic niche in relation to the nomads. The nomads lacked many goods that they were largely incapable of making themselves, such tools, kitchenware, medicine, firearms, etc, as well as prestige or luxury items such as mirrors, jewelry, clothing, etc. These items were greatly valued by nomadic populations, and could only acquired though trade with sedentary communities who could produce such goods. Thus, nomads tended to orbit around sedentary communities with whom they could trade. As a result, many nomads were not totally nomadic. As Owen Lattimore said, “a pure nomad is a poor nomad.” What the nomads did have was an abundance of livestock. The nomad’s animal products could be traded with sedentary communities who needed meat, milk, butter, leather, etc. Trade with Russia made the nomads quite wealthier, and helped make their lives easier. Conversely, the Russians took away their freedom. Through trade and administrative control, the nomads were increasingly fixed to points on the map, Russians farmers increasingly took away their grazing lands, and ultimately the nomads lost their freedom as natural predators. Thus in the end Russian colonization was a mixed blessing.

For more on the economic dynamics between nomads and sedentary communities, I would recommend “Nomads and the Outside World” and “Nomads in the Sedentary World”, both by Anatoly Khazanov.

The Naryn Fortification

Н. Л. Зеланд. Кашгария и перевалы Тянь-Шаня. Путевые записки // Записки Западно-Сибирского отдела Императорского Русского географического общества. Книжка IX. 1888.

Before the entrance of the vast Dolon1 valley the coachman told me that Kyrgyz barantchis2 have chosen the mountains and the surrounding regions as their den, and prey on the Sarts,3 Dungans4 and others who pass by here without weapons. They take their horses and other things they find. But they do not brother the Russians, because they suspect them to have firearms, whereas they are only armed with pikes for the most part. Indeed, when we drove into the valley something began stir up above, and a bunch of riders started to move up and down, back and forth along the mountain heights. That of course, was end of the affair, as the barantchis were satisfied with their menacing stares sent down against us, who received in response a mocking smile from our coachman. Generally, despite the persecution from the administration, baranta in the different remote corners of Semireche5 has not yet entirely faded away entirely, and the robbery of cattle still occurs here and there, but rarely do affairs reach the point of murder.

When we entered the Dolon Pass, we found snow on the sides of the mountains nearly up to the road. And no wonder, this pass has been noted to be 9800 feet above sea level. From the pass, like a point, several mountain ranges are directed outwards from various sides.

From the pass we descended into a long and very picturesque gorge, with the river Ottuk flowing along the valley’s bottom. Here, eyes are suddenly presented with livelier, softer pictures. A fir tree appears, something that has not been seen since Verny.6 Generally, there are forests only along the northern sides of the Tianshan, and in places where there is more precipitation due to the meeting of warm westerly and cold easterly winds. Snow, in turn, contributes to the accumulation of moisture.

At first, scattered clusters of fir trees were encountered, then entire forests in picturesque groups, distributed along the sides and on top on the mountains. In one place the trees descended in a wide stream down the mountain, another set of trees stand straight like they are a row of soldiers. A third set are like a green wall of fir trees in each fold of the mountains that run up to the very top of the peaks. In the gaps of the forest a bright green carpet of alpine grass was visible, with the golden shade of autumn here and there, and from under this place sections of the mountains were visible which appeared as grey, bluish, and red jagged teeth, and wrinkly stripes of the mountainous lime and sand stone. Thoughts arrival to a person’s head in a most unexpected way: the sight of one place in this gorge suddenly reminded me of an alpine view, from a painting that I saw in childhood, depicting Henry IV7 as a pilgrim, when he was so pitifully setting out across the Alps to honor Hildebrandt. The local landscapes really do remind me of the Alps, from what I saw while travelling from Verona across Brenner8 to Bavaria.

Riding up the stantisa,9 I could see log izbas10 that I had not seen in a long time, one of which was being used by the stantsia. Thus, there are forests in abundance. In the mountains, those that Verny11 lies at the feet of, there are many spruce forests that decorate the landscape, but using their wood to build home is forbidden there, as in the rest of Semireche.12

The next stantsia – another curious sight on the road: the bottom of the Ottuk gorge runs a river so windingly that it needs to be forded 30 times. At some places the water is up to the belly of the horse, and this is considered to be low. When the was water was high it flipped a dozen and half bridges over with their backs exposed, which says something about the local environment. In springtime, people are forced to entirely abandon the postal road at times and carry their packs somewhere higher up into the mountains. The boredom from this nearly continuous fording of the river a little redeemed by the beautiful setting: slender spruce trees cover both sides from the gorge from top to the very bottom, so that it is like travelling through a forest here. Poking out from between the ephedra bushes are rowan, rosehip, barberry, etc. At the end, the gorge exits on to a smooth steppe road. It continues along a high valley framed by high mountains, which are in large part covered by wilted grass. Signs of life are encountered here again, patches of barley sown by the Kyrgyz as well as haystacks. The latter indicates that the Kyrgyz – some at the very least – have acknowledged the disaster that befell the Naryn volost13 this past winter. It is known that the majority of these nomads until now did not consider it necessary to buildup food supplies for their animals for the winter, and instead expected them to forge for grass from under the snow. But in the winter of 1885-1886, after a snow fall it briefly thawed but froze again. The cattle could not reach the grass under the ice and died in great numbers. On average, from 10 sheep only one remained.

The Naryn River is clear here, not stormy and already quite wide (the Naryn is nothing other than the beginning of the Sry-Darya. It is not uncommon in Middle Asia that the same river has different names at different places along its course), and on its left bank there is a fortification. It cannot be a called an excellent fortification. A short wall, ramparts, ditch and barracks house a team of 100 people, a half sotnya14 of Cossacks and few pieces of artillery. This all is only scary for Asians, but that is all that is required. Naryn, due to its remoteness and desertedness, is one of those flashpoints on the outskirts of our country that service people usually avoid, as it is seen as a form of exile.15 What is there to do! It is impossible to do without these places, - they are the forwards links in a chain of Russian settlements which are being created in the Muslim and Chinese east, step by step, reclaiming this land from Asian barbarism. That these words are not overly strong, we will see below. It seems to me, that everyone who has lived a year or more in such a place has in some way earned the right to be called a pioneer of civilization, and it would be fair that service in such isolated points, at the very least, should come with some privileges, which however do not yet exist. Nowhere else than in these barren corners does the atmosphere depend on the quality of the local senior commander. Naryn currently is quite lucky in terms of this. The influence of K. A. Larionov, who combines education and knowledge of the region with dignity of character, can be said to be very beneficial. His wife assists him with this, who in the past has accompanied him in all of the research expeditions in this region for topographical and meteorological purposes.

The settlement of Naryn itself, which is located outside of the fortification, is quite nice and almost entirely commercial. It has several streets that are long, wide and clean. The homes are made from mud bricks, with flat roofs and fenced front gardens. The greenery of the later is mostly willow. The main street consists of markets and shopping places, shops which are exclusively Asian, whose owners are in part Tatar and mostly black bearded Sarts16 in robes and turbans. Trade from Kashgar mainly passes through here. The number of merchants here is about 300.

The area around Naryn is unattractive. Located in a basin and surrounded by barren yellowish grey mountains, our soldiers call it a “punishment cell” due to its lack of horizon. In some places in the distance, there are a few spots where short spruce trees can be seen. The soil is amazingly dense, as it consists of loam17 mixed with tiny pebbles. The water is relatively rich in lime, which generally is common in the local mountains. There is also a rich deposit of alabaster. The climate, due the high location (7000-8000 feet above sea level), is very cold. Cabbage does not grow here, and potatoes only fair a little better than hazelnuts. Due to the cold climate, density of the soil, lack of swamps, relatively clean water, wide and clean streets, Naryn is one of the healthier places to live in Semireche,18 about which is evidenced by the good supply of quinine19 that is stored in the local pharmacy in the infirmary, whereas it is constantly in short supply elsewhere. However it should be noted that visitors here often suffer from nervous seizures – headaches, feeling short of breath and pointless spiritual depression, which is all partially explained by the location’s elevation.

While walking through Nayrn’s market place, I was witness to a very oriental scene. The benches, steps and rubble in front of a few shops were covered by the robe-wearing crowd. From the white bearded elders with white turbans to the barefooted boys sitting, they all seem petrified, their eyes fixed on a person walking back and forth along the street at some distance from the shops. The subject is wearing a white turban with a yellow sash and a silk robe, and speaking with a loud voice. Then he halts, stretches forth his arms, raising his voice and widening his eyes, then walking at an quickened pace, speaks quickly again before then sitting down as if he is in deep thought, speaking almost in a whisper, then again going into pathos, and in a word, improvising something very heartwarming. This, as it turns out, was a wandering storyteller or a lecturer, teaching the lives of Muslim saints. His craft is very profitable, he carried a gift in his hands.

А. Д. Соколов. Тогуз-Торау. (По новой дороге из Семиречья в Фергану.) — Верный, 1908.

The Naryn fortification (570.5 verstas20 from Verny) with in commercial center is located on the left bank of the river in a narrow river valley, similar to a pit, with the surrounding mountains towering above nearly everywhere and completely hiding the fortification from the eyes of travelers. Higher along the course of the river the valley narrows, and below (from the west) it is closed by the ranges of Naryn-Tau, Ak-Kiya, which makes the valley into a closed basin. At the bottom of the basin there is a fortress, built in 1868 by Major-General Ya. I. Kraevsky. Almost opposite the fortress on the steep southern slopes of the Naryn-Tau, a narrow gorge (Sharkratma) is visible, through which runs the road to Atbash and to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan. To the west down the Naryn river to Andijan.21 The road laid out by sappers was supposed to be suitable for wheeled vehicles, but later it turned out not to live up its expectations, or to be worth its cost (more than 100 thousand rubles).

Having gone down the soft clay escarpment into the valley and gone over a wooden bridge over the quick flowing Naryn, we turned west to the fortress. To the left from the road, an infirmary is located at the very feet of the forested mountains, along with a vast garden, and a little further a row of white custom buildings could be seen. To the western side of the fortress there is a small village or trading settlement, nearly entirely populated by Sarts and Taters who trade with the local Kyrgyz.

Interesting information about population: according to information for the year 1903, the Russian population of Naryn was 391 (including soldiers, Cossacks and frontier guards) and 484 foreigners, in total 875 people. (According to the information from the year 1906, the figures are are follows: 290 Russians, and 712 foreigners, 1011 people in total, and among them are 93 Tatars, 397 Sarts (Review of the Semireche Oblast for the year 1900)).

Such an insignificant population is explained by the fact that, despite being a crossroads for Andijan and Kashgar, the living conditions in Naryn are difficult. The location of the fortification is very southerly compared to other settlements in the region (41° 26′ N), the climate is very dry, average annual temperature is -2.9°, and in winter temperatures reach -30 and -32 °C with frequent cold winds, as observed by the local meteorological station. The main reason for this is the region’s altitude, which reaches more than 6600 feet above sea level, and the completely enclosed nature of this narrow and deep valley that is surrounded by tall, snowy mountains.

There is no agriculture or gardening there, thus bread, greens and fruits are all imported. Watermelons, melons and apples are brought from Przhevalsk22 and Verny, and apricots, peaches and grapes are brought from Kashgar by donkeys carrying them in packs. It was once a widespread opinion that it was entirely impossible to grow anything at the Naryn fortification because of the cold, but this seems to be not entirely correct. Currently below the city along the Naryn valley to the Ak-Kiya pass there are arable lands, and the general population, seemingly, as began to pay more attention to this matter. A few years ago, as was told by a resident, it was impossible to find fresh cabbage or potatoes in Naryn, but today this can all be purchased locally. But is difficult to find is baked bread. For the needs of the local Muslim population lepeshka23 can be found at the local bazar, but not Russian bread. According to the advice of a headman, I had to go the Russian merchant who took about a ruble for a loaf of low quality bread, and made it clear that he, as a seller of bread, does this for us as a small favor, for which we should be grateful for. As there were no further Russian settlements along the Naryn river and nowhere else to find bread further along the way, we accepted this valuable blessing. The population of this settlement, as I already mentioned, consists almost entirely of Sarts and Tatars occupied in trade with the Kyrgyz, bartering their goods in exchange for cattle. Here it should be once again noted that all of the trade in Semireche with the nomads is in the hands of the Sarts and Tatars, who hold the natives in a nearly total economic dependence. There is also a P-va store here, but it almost exclusively serves the Russian population of the fortress. The bazar is not very lively. The distinctive particularity of the bazar is the abundance of Kyrgyz and Kashgarlik (Sarts from Kashgar), and rarely, rarely will a uniform cap of a Russian flash through the crowd. On the question of whether the new road to Andijan has revived trade in this place, I heard that is not suitable for wheeled vehicles and thus it is not used at all, with the exception of a few places and where bridges cross large rivers. There is only a lively caravan trade coming from Kashgar here, which delivers mata (cotton fabric), furs, skins, etc, and other raw goods.

The Dolon pass leads from Lake Issyk Kul to Naryn. Zeland is traveling from the north to the south, to Naryn.

From the word “baranta”, a Turkic word for stealing cattle, sheep and other goods

Ethnonym for the farming people of Central Asia

Chinese Muslims, also called Hui in Chinese. Not to be confused with modern day Uyghurs, the people of the Tarim Basin

“Seven Rivers”. A region of southeastern corner of modern Kazakhstan, between Lake Balkhash and the Tianshan Mountains. The seven rivers all follow into Lake Balkhash

Modern day Almaty, the main city in Semireche

King of France, 1589-1610

The Brenner Pass, connecting Italy to Austria

A Cossack settlement

Traditional Russian log cabin

Modern day Almaty. The mountains are the Trans-Ili Alatau

Region of modern day southeastern Kazakhstan. The name means “Sever Rivers”, referring to the seven rivers which flow into Lake Balkhash

Russian territorial administrative unit

A sotnya were 100 Cossacks, so there are 50 Cossacks here

This sentence was awkward to translate, original says: Нарын, по отдаленности и пустынности своей, одно из тех злачных мест наших окраин, которых служащие наши обыкновенно избегают как ссылки на поселение.

And old, general term from the sedentary peoples of Central Asia. Mostly correlates to population of modern day Uzbekistan

A type of soil that is mixed heavily with sand, silt and clay

Modern day southeastern Kazakhstan. Semireche means “Seven rivers”, those that flow into Lake Balkhash

Used to malaria

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 kilometer/3,500 feet

Located in the Fergana Valley

Named after the explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky. Today known as Karakol, at the eastern end of Lake Issyk Kul, which is located between Semireche and Naryn

Flatbread, common to Central Asia and other nearby countries

Beautiful pics from a beautiful area.

Henry IV is the 11th C HRE emperor and Hildebrand is Pope Gregory VII The crossing of the Alps was part of the emperor's penitential walk to Canossa when the pope humiliated the emperor during the Investiture Controversy. Interesting to see such a reference in a 19th C russian report about the Tianshan.