Across the Southern Altai Mountains (2/2) - Grigory Spassky, 1809

Translation of a journey across the mountains of south Siberia - Russian settlements, Altai's ancient past, and the "rock-people"

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is part two of my translation of Grigory Ivanovich Spassky’s Путешествие по Южном Алтайским Горам (“A Journey Across the Altai Mountains”). Part one can be read here. For the full introduction of this translation, including details on the history of the Altai Mountains, the “chuds”, and the “rock people”, see part one. The source for this translation can be found here.

For more on the history of the Bukhtarma region, see “Travels in the Country of the Rock People” (Путешествие в страну каменщиков), by the local historian Alexander Grigorevich Lukhtanov. This work is in Russian, can be found here, and downloaded here.

Village of Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya1, 7 July

Very early in the morning we headed out from Korobishenskaya. My companions were forced to take a different road. They went along the left bank of the Bukhtarma as it was the more convenient for transporting the taradaek2 with provisions and the mountain instruments - and I set off along the right bank, escorted by one of the residents from the village Korobishenskaya and a miner, who was armed and having two hunting dogs with them and was with me during nearly all of my travels across the Southern Altai Mountains.

From Korobishenskaya we boarded a small boat and crossed over to the right bank of the river. Our boat was taken downstream by more than a verst by the quick current of the water, despite the skill of the rower, while the horse swam across as per local custom and the dog made it to shore much further downstream.

The courage and agility of the young rock people, who led the horses in crossing over the river, was incredible. They swam beside the horses, holding them by their manes, plunging them into the water and then swimming back up to the surface. They were having fun by the time they finished this trip as this was normal for them, but for any others it was dangerous, and within an hour they returned home in our boat.

The mountains, lying along both banks of the Bukhtarma, are made from granite, gneiss and slate, cut by quartz and lime. Along the left bank of the river the mountains stand at some distance, and represent a convenient route for travel, while along the right bank parts of these rocky cliffs adjoin with the water. Here the road, or better called a trail, is only usable on horseback, and it constantly twists and turns: sometimes it descends on to the horizon of the river, or coils like a snail ascending up the mountains. Together with these changes, the traveler is also exposed to various impressions. Fear seizes him at the feet of the mountains, under the overhanging rocks, as if they are waiting to fall on him, and on the other hand, he is brought to delight when he sees new locations from of the heights of the mountains.

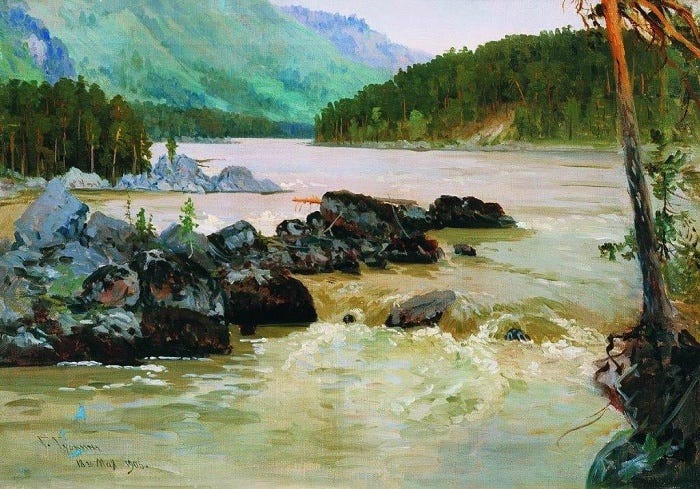

Many fallen boulders lie along the shore, others in the river, protruding from under a thin layer of water. In the first case, the traveler must closely pass by them with some difficultly; and in the other case they create rapids in the river that are impassable for even the bravest swimmer. As the water tumbles down over the rocks, it produces quite a bit of noise. From a distant it is similar to what we hear when we are approach a well-populated city. - This analogy can not only be applied to this place, but to many other rivers in the high mountains which are usually accompanied by a similar noise, especially when the water level is low.

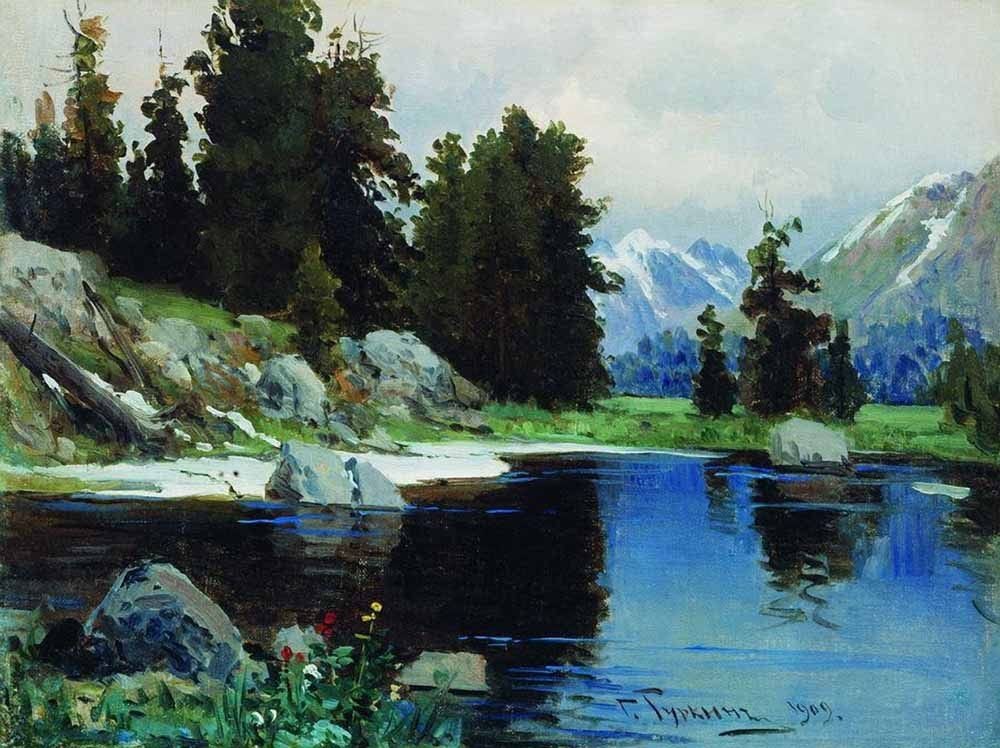

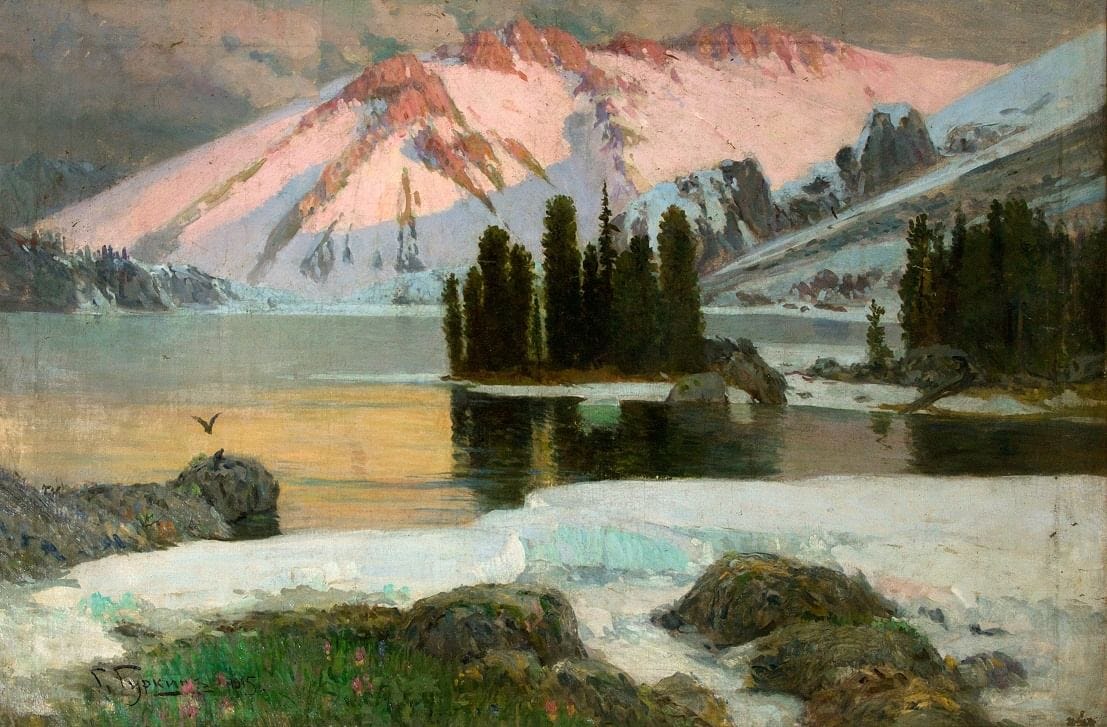

After 15 versts from Korobishenskaya and 5 from Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, the mountains from the bank of the river Bukhtarma deviate to the east. - Around here the view opens to a charming picture, and nor have I seen any similar view before, as it could only be captured by a brush that paints the earth's surface. A traveler is struck all of a sudden, as if carried off by the wild natural power of this place, where all that is great and elegant is joined as a sensation. His gaze embraces in one moment many boundless and innumerable things. Here under his feet one of the most wonderful of valleys spreads out, animated by the noise of a river rushing through and decorated by a carpet of greenery. From the first glance it seems that this valley being surrounded on all sides by mountains is like a vast amphitheater, but considering the details you find that the mountains have various heights and face different directions, and are separated by a large distance. From the western and eastern side they stretch out along two ridge lines, which come near the Bukhtarma, descending as if they do not dare look upon the majestic Kurchum range3 that proudly towers between them.

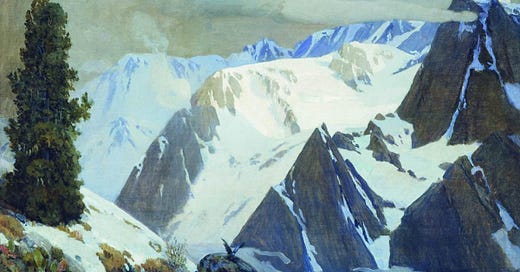

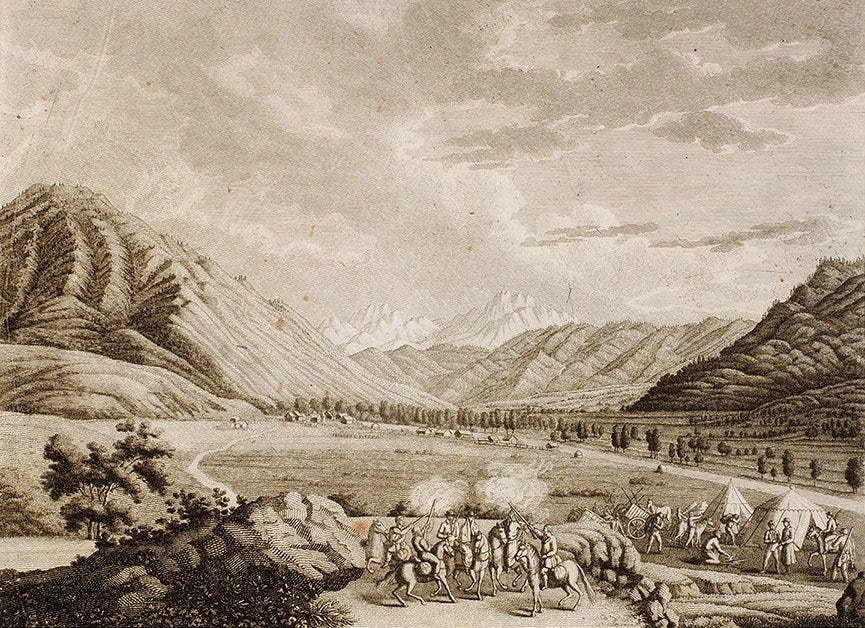

This range is the main object shown on the map, of which no brush or feather can depict precisely, and the view attached here represents only one of its weaker shades. Giant boulders rise on the brow of the Kurchum range, which lie somewhat randomly on the peaks. Their profile seems different depending on the sides from which they are looked at. From here they can be likened to giant ruins, with many pyramids and points sticking out. All these rocks, as well as the mountain range itself are covered with snow as far as the eyes can see. The gloomy rocks, eternally green trees on the mountain slopes and dazzling white snow have a striking contrast with the clear sky and clouds that lie behind the mountains on an endless horizon.

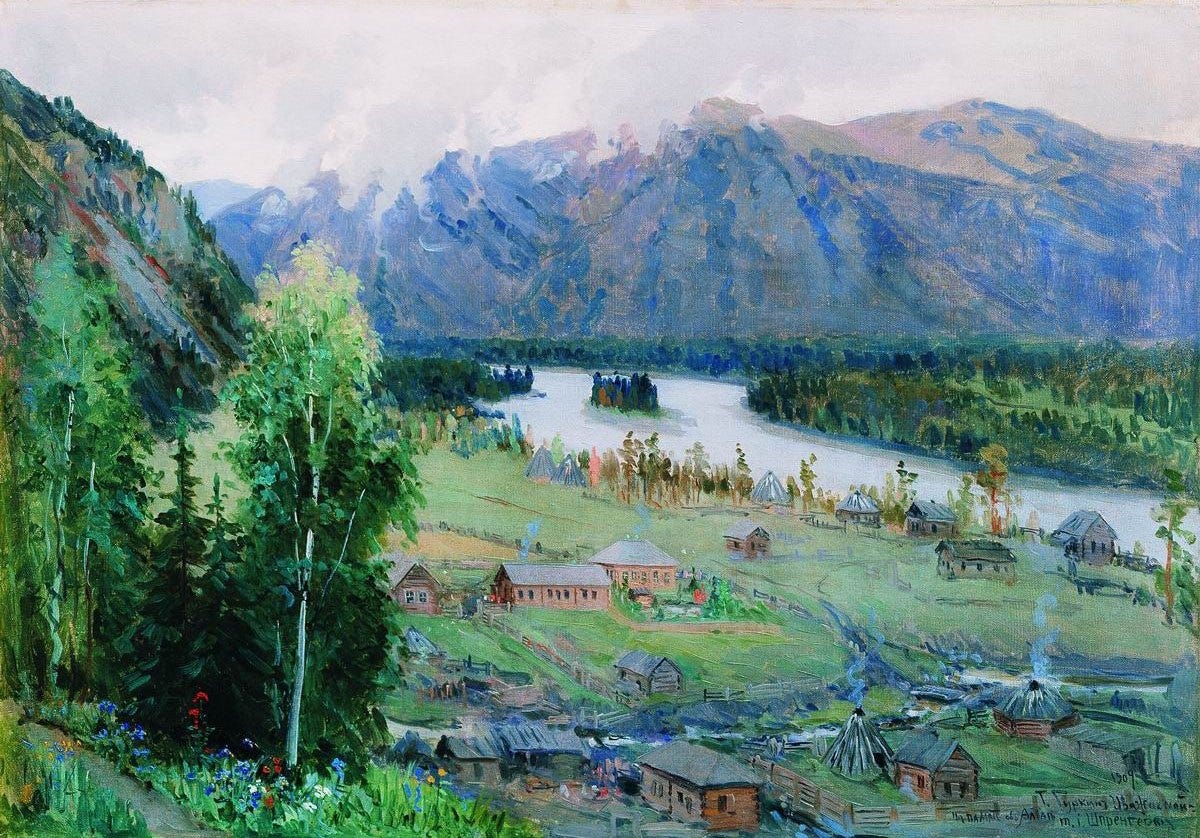

On the afternoon side of the valley,4 on the right bank of the Bukhtarma and at the foot of a tall granite mountain is the location of the rock people village of Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, also known as Pechishchenskaya. Its first name is from the river which flows beside it, while its other name is from a cave that is similar to a furnace's mouth, which is visible from the shore of the river near this village. The village Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya is inhabited by 20 hospitable families of rock people. Beside the village down the river, a few poor Kyrgyz5 live in yurts: in the summer they graze their horses and horned cattle, and in the winter they help the villagers with house work in exchange for food. These Kyrgyz, having all possibilities to live in houses, yet do not want to part from their yurts. They patiently endure the cruelest winter freezes, yet do not envy the lives of the rock people. How difficult it is to overcome the force of habit!

Although we traveled very quietly and often halted, we still reached our destination before our companions did. Opposite the village they crossed over the Bukhtarma. I ordered them to settle down near the Kyrgyz yurts to relax; there we set up our tents. From the village our camp could be seen. We stayed there for more than a day.

Village Belaya, 9 July

The Listvennichny, or Listvyazhnoy range begins next to the river Bukhtarma, running along its right bank to the river Chernaya, itself on a high ridge that occasionally has sharp hills towards its end. It gained its name from larches,6 which grow on it in greater numbers than firs, pines, poplars, birches and other trees. The Listvennichny range extends for a distance of about 60 versts, and with a width up to 15. The mountains from their beginning to the mouth of the river Belaya, which cuts through it, are called the Small Listvyazhny range, and the mountains going further to the range's end are the Big Listvyazhny range. The names are from the different heights of the mountains. The main mass of the first is from granite, shale and slate calcareous stone with quartz veins, and the second are granite and greenish ladder.7

The Listvyazhny range served as a refuge for the rock people during their period of exile and self-governance.8 They, persecuted by the state, hid away in the most impregnable places and caves, which are plentiful here, especially in the limestone mountains, and some of these caves are very wide and quite comfortable, like those on the river Chernaya at the mouth of the river Arkhipikhi, where the remains of the former inhabitants can still be seen today.9 Sometimes in these caves there is soil with saltpeter.10 This soil appears white like salt, also as greyish-white and bluish-white. These caves are 15 versts from the village Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, located between the left bank of the river Bukhtarma and the right bank of the river Sogornaya, before the mouth of the river Belaya. These caves have a depth from 1 to 4 arshins.

Having traveled some distance from the village Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, we rose up to an elevated plain watered by streams from the Small Listvyazhny range. - The right side of this range extends outwards, and to the left of the mountains, going from the right bank of the river Bukhtarma along various creeks, which are the Yazovaya, Poskocha and Okoleikha, along which the rock people have never lived. - These last mountains have many cliffs, high and impregnable. People alone, inclined or even enthusiastic about living in this desert,11 could chose such a wild place for themselves to live. Darkness reigns eternally here, and the beneficial rays of the sun do not illuminate anything in these gorges. These places are not only horrible for people, but for any kind of animal as well! Often promyshlenniki12 find the wildest animals buried by the winter snow here, and in summer they are seen to be shattered into pieces after falling from the rocky cliffs. They say that the small river Poskochi received its name from the giant rocks lying in it, and when horses cross the river they must constantly gallop, which is considerably dangerous for the rider. The Okoleikha is the same, deserving its name with its sheer wildness in comparison to other places and its impregnableness, and received its name from the few rock people hiding out there, who gave it the nickname Okoleevy.

It is worth noting, that almost all of the places where the rock people live have Russian names, unlike other parts of Siberia where the names that have come from the depths of ancient times have been preserved.13 If these places were not inhabited prior to the rock people - to which, however, is opposite is testified to by the ancient remains found here,14 - then at least animals must have attracted people to live in this area, and in this case it could explain the origin of their names, to which, apparently, were borrowed for this and other places in Siberia: there is not one corner of this land, where every remarkable object does not a name.

It is necessary to think, that the secrecy the rock people attempted when they first settled here, had hindered them from learning of what others had called these places before, and necessarily forced them to invent names themselves, so as not to be ignorant of the places so close to them.

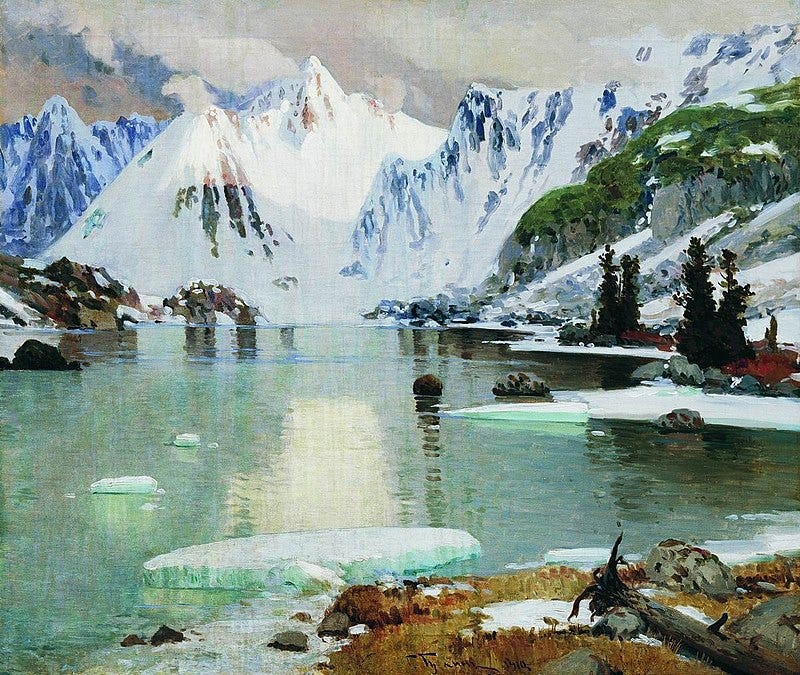

After 15 versts from Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, the noisy flowing river Sovrasovska and the Listvyazhny range turns towards sun at noon.15 Traveling through the Sovrasovska a few times, we rose up a high mountain and then descended again onto a pleasant plain that is watered by the river Belaya. Although this river is not very wide, it is extremely quick and dangerous to cross. It flows out from Maral Lake, near the village Fykalki, and flows into the river Bukhtarma near the village Belaya. We went across the river Belaya at the ford opposite this village itself. It lays 22 versts from Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya, at the end of the Small Listvyazhny range and at the beginning of the Big Listvyazhny range. Located there are 16 households of rock people. This village is remarkable because from there, the river Belaya turns towards the midday sun,16 passing through the Listvyazhny range, where between the mountains it opens up to a pin-shaped hill of the Kurchum range, covered in snow which gives this place a great view.

Village of Fykalka,17 11 July

On the next day we headed from Belaya to Fykalka. The sky was clear and the weather was favorable, but damp, with mist rising from the slopes and peaks of the northern mountains and hills which heralded a change. Residents of Siberia talk about this phenomenon, where the hills drown with mist. In fact, it seems that from afar the vapor comes out from the mountains similar to smoke. It has been noticed that if the vapor rises higher, then there will be bad weather soon after, and if the vapor descends then this serves as a harbinger of good weather. - The horizon darkened more and more; by the end all the mountains from their very peaks to their foundations and even the plains were covered by such a thick darkness that things 10 steps in front of you were indistinguishable.

Riding up to Fykalki, together with the most beautiful sight of the Listvyazhny range with surrounding mountains - presented in the view attached here - a sea of fog opens up to us, one without a bottom, nor shore, and village itself could not be seen, even when we were right before it. The consequence of this fog was torrential rain, which continued for the entire day and night, and in the mountains there was snow fall; the so-called Shchebenyukha differed from all other mountains with its sheer whiteness. Good weather came again in the morning and continued our entire time in the Listvyazhny mountains, where we went to in order to work on opening a mining shaft on its midday side.

The village Fykalka lies in a valley that is enclosed by two mountain ranges: located on the right side are the Big Listvyazhny range, and on the left is accompanied by the river Belaya. Between them in the distance are the blue peaks of the Katun mountains. In the Listvyazhny range stands a solitary, sharp and round hill covered in show and stony rubble, the reason it is named Shchebenyukha.18 Although it is taller than all the surrounding mountains, its height nevertheless does not reach the snow line. Much of the small granite lying on this hill has collapsed into small pieces of rubble indicating that this mountain was much higher before than it is now.

Fykalka is 25 versts from the village Belaya. It has only 12 homes, which are located along both side of a stream that flows into the river Belaya nearby, and because it is one of the first settlements of yasak paying19 peasants, or rock people, which I have mentioned a few times already, and I intend to report in some details about them here.

News about the rock people

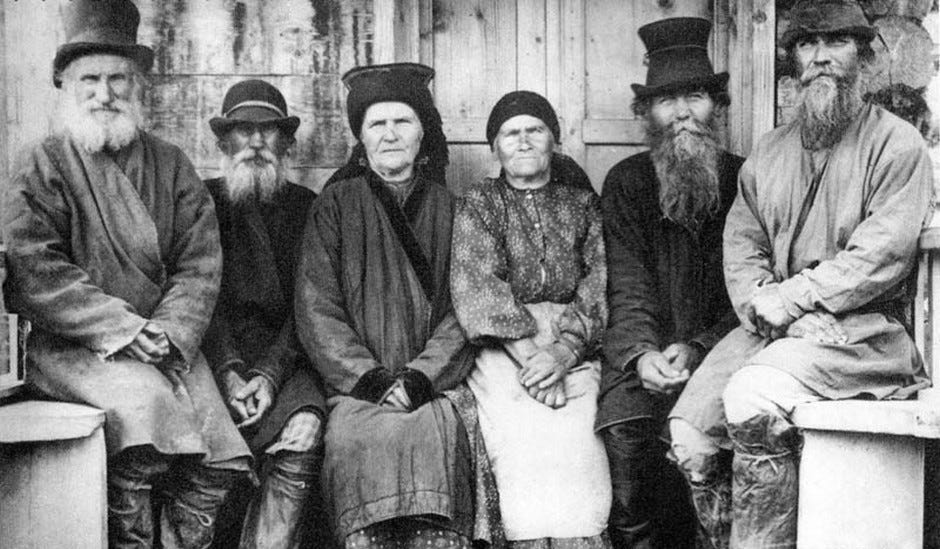

They are Siberian residents, inhabitants of this local mountainous country, and are generally known by the word “rock”, and said in the rocks or behind them. From these typical customs they received the name “rock people”, and are also known under the title of yasak paying peasants.

The rock people, similar as the Swiss, inhabit the most mountainous places of southern Siberia and live within the boundaries of the Tomsk guberniya20 of the Biya uezda.21 They somehow use the law of two estates, peasant and yasak, and are managed by the Biya zemstvo court22 through a special official who resides in the Semipalatinak fortress,23 and a general office was established in one of their settlements by the volost24 authorities.

They began paying the treasury according to the example set by the yasak peoples by giving an animal’s fur pelt, and for this reason they are called yasak. At a later time this tribute was changed to money which they pay, yet, at all possibilities they will contribute with the first form of payments because the region they occupy is abundant with animals and they hunt them with no less success than nomadic peoples, and besides, the local sables are of a very high quality. The number of these yasak people according to the first census of them, which served as the basis for assessing their yasak contribution, was 1 man for every 300 people.25 (According to the last 7 revisions, the census counted 313 males, and 314 female souls.).

The first settlement in this country was made about 50 years ago, and consisted of only 4 people who withdrew here due to a pious inclination. They founded their residence on the river Ulba, the same side as the mountains named Kholzun;26 but as one of their comrades was caught and their hiding place discovered, they all, fearing a similar fate, went over into the silent and wild gorges of the Bukhtarma. But there, despite the spot's congeniality, and whether due to inclination or their communal nature, or the need to feed themselves, they could not remain in absolutely isolation. Little by little they began showing up in nearby Russian villages, and especially in those where most residents were prone to the Old Believer schism. Their piety and humility, whether truthful or double faced, attracted new residents to them. They were greatly respected, which earned them much to eat, and by portraying their refuge as attractively as possible many were inclined to escape to them. - Many of the residents, being blinded by such seductive narratives, left their homes and moved with their wives and children to another land, which at that time was deserted and unknown.

In a short time they gathered a large enough number of residents, most of whom were peasants. They built themselves huts along the banks of the rivers Bukhtarma, Belaya Yazovoy and another river, where the wildness of nature is joined with some conveniences for herding cattle and farming. Their dwellings are fenced on all sides by the highest mountains and rivers both fast and wide. They lived peacefully, strictly observing their sacred faith and laws. Even land that was not cultivated generously rewarded the farmers; hunting brought innumerable riches to the promyshlenniki. - In a word, they would have been absolutely content if there were no restless people among their comrades.

Although the authorities took some measures against these fugitives, but due to the inaccessibility and the obscurity of their dwellings, the authorities could be neither certain where they were located or take action against them. Meanwhile, rumors and gossip spread about them, which attracted new comers to their settlements. These new comers were in large part fugitive soldiers, factory workers, punished and unpunished criminals and other similar types of people. As they settled every kind of disorder increased, of a kind that only unbridled liberty can produce. Violence followed, then theft and even murder. Together with this, there was a noticeable shortage of women compared to the number of men: kidnappings of wives and daughters began; strife and criminality took the place of quiet and productivity. - The criminals remained without punishment or were persecuted by the vengeance of the offended. No was secure in what they owned. Calamitous anarchy in even the smallest of societies!

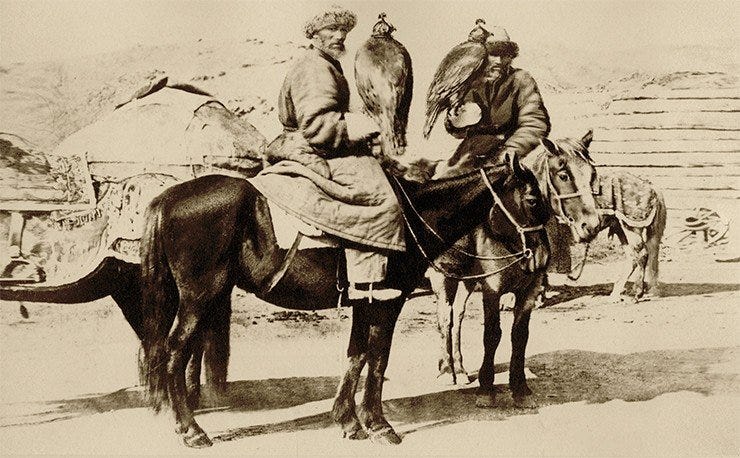

All of these consequences caused the local authorities to turn and give special attention to these mountain dwellers, often sending military teams to pursue them; but these wild gorges defended them every search, and the teams for the most part returned without success. The Chinese also looked indifferently at the insults that the rock people inflict upon the Kyrgyz that live beyond the Irtysh, and any efforts they made to prevent them were useless. The Kyrgyz, however, try not to be in debt: they are very much able to pay insult for insult.

Such was the station of the rock people. Some of them, innocent of the wicked deeds committed by their depraved comrades, already began thinking about their own security. The consequence of this was that punishments were to be decided by a common verdict for those accused of crimes. Once, the punishment was carried out in the following way: two prisoners were attached to a small raft and launched into the fast Bukhtarma: they were given a pole to save themselves from drowning if the occasion arose, and one piece of bread to eat; and indeed, one of them drowned, and the other reached shore without further harm. But as this example could not restore the desired order, they turned to one of the most restless person, which were Bykov and Zagumennoy. They attempted to catch these brave rock people with all of their accomplices and sentence them to punishment. Only luck saved them. - At the very moment, when the people were gathered and the punishment was being prepared, a Chinese border official unexpectedly arrived with armed men. One of the rock people somehow shot one of the armed men (tchurchuta27). The official was enraged by this act and ordered his men to surround the rock people on all sides, and upon learning the reason for why the crowd had assembled, he demanded they quickly free the convicted unless they wanted to be subjected to the same fate as what was prepared for the convicted. No matter how much the rock people protested that the murder of the tchurchuta was unintentional and that their comrades deserved to be punished, the Chinese official did not want to listen and would not leave before they did what he ordered. Bykov and Zagumennoy with their accomplices, freed themselves from upcoming trouble, and began again to continue their craft and tried to seek revenge for the disgrace inflicted upon them.

After this incident, the rock people condemned the bravest of their comrades and could no longer hope that the calm would be restored; and a new disaster was added to this - there was a crop failure in their country which lasted three summers in a row. They did not wish for anything more than to leave this place, it was made horrible for them and they hoped returned to their former homes but the fear of the punishments they deserved held them back. In the end they decided they would seek protection from the Chinese. They collected a few families, numbering 60 people, and headed to the Chinese frontier outpost of Chingistai,28 which is 55 versts from the current village of Fykalki. First, they stopped at some distance from this outpost, and sent 6 of their comrades to it in order to find out the opinion of the local noyen,29 or the frontier official, about their thoughts on the rock peoples' plan. But as the messengers they sent there were arrested, they did not going to wait for their return any longer, decided to go to the noyen with their wives and children. Upon their arrival to Chingistai, they were quickly escorted under supervision by the Tchurchuta to Khobdo,30 a Chinese city in Tatary.

They were sent there on horseback, with which the noyen provided them, and in large part they went across mountainous places. Having been on the road for nearly a month, they arrived to Khobdo and were presented to the local commander, who after collecting information from them ordered them to be placed together in a few buildings, a barracks of sort, or maybe better described as a prison. They were held there for more than enough time under strict supervision, receiving however, enough food and care. They were then freed and it was announced to them that a decree had been received from the Bogdo-khan31 in Beijing, which said he did not agree to accept them as his citizens. But in respect of their poverty, the Bogdo-khan ordered them to be given food and returned to where they came from. After this, they were quickly sent back along the same way they had come to Khobdo: they were given horses to ride, also sheep and sarachin millet32 to eat.

They were very happy about this decision regarding their fate, as executions were often carried out before their eyes which gave them a bad impression of the Chinese people and authorities. With surprise they noted that the Chinese not only punished the thief, but also the victim of the theft, as it was his oversight that allowed the theft to occur.33

Upon their return, although the Chinese frontier officials had provided them patronage, they boldly undertook to prepare defenses from all harassment, like their runaway brothers and their neighboring Kyrgyz. But this could not, however, deter all internal disturbances; the danger of being caught and punished also did not cease to torment them. Such a way of life was accompanied by everlasting violence and fear, and at the same time rumors reached the rock people about the boundless mercy of Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna34 awakened their voice of conscious not only among the more well-minded ones, but all the others as well. They unanimously agreed to leave their lives of isolation and accept the rule of law. With this intention they sent their society a fugitive dragoon, nicknamed Bykov, to the Bukhtarminsky mine as nearest comfortable place. The local mining official gave a prudent and favorable acceptance to Bykov's request, which prompted the other rock people to go there together with Bykov and confirm their common desire to come back under the law. The official, having accepted the wish of the rock people, did not delay in bring information on this important event to the commander, and with the proper certification, it was submitted to the Highest discretion of the Empress. Not in vain were the hopes of these people, despite being seduced by a vicious inclination and sent on a delusional path. They were prescribed the following laws: by mercy of the monarch, depicted in the most High rescript, given to the former governor-general of Siberia Pil on the day of 15 September, in the year 1791, joined them to the number of loyal subjects, under the name yasak.

Mercy, bestowed to these people, completely put an end to all the confusion between them and restored betterment and agreement amongst them. They left their horrible cliffs and gorges, these silent witnesses to their crimes and turmoil of their wayward life,35 and settled in places that have all possible comforts of the local country for communicating with one place to another, and for agriculture and raising cattle. They live there to this day. Their villages along the bank of the Bukhtarma are as follows: Osochikha, Bykova, Sennaya, Korobishenskaya and Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya; and in other places the main villages are Malonarymskaya, Yazovaya, Belaya and Fykalka. Located in almost every village is a prayer room, but not one of them have a church, because generally all of residents are devoted to the Old Believe. A few old men and scribes are chosen from their brethren to fulfill all requirements and sacred duties. Only for weddings do they go the Bukhtarminskaya fortress. The view represents a special ritual observed by the rock people during their weddings. They meet and fellow the newlyweds with gunfire, firing into the sky. The bride puts a man's hat above her above her large veil.

The homes of the rock people are such the same as in other places in Siberia, where there is enough timber. I did not notice anything special in their way of life, nor in their home life, nor in anything else when compared to other Siberian old-timers. Only one difference between the rock people and the others, is what they probably received from independent life and practice in hunting: this is their courage, nimbleness and some coarseness in manners, giving them a warlike appearance, which is all the more noticeable as they travel armed with rifles for the most part, in case of danger from predatory animal that are common in the local country.

The typical occupations for rock people are agriculture, cattle herding and hunting. They are engaged in trade with Chinese citizens who guard the border, and also trade with the Kyrgyz. Much of their trade is barter: goods they receive from the Kyrgyz are given to Chinese instead of cash payments. - This is usually as such: kitaiki,36 silk, porcelain, clay and wooden cups, flint, brick tea37 and more. Sometimes, which is currently very rare, they exchange sliver and silk fabrics, as such: kanchi, a type of headdress, kanfa, similar to a satin, and fanzas of a very low kindness.38 — From the Kyrgyz they receive horses and horned cattle, saddles, reigns, felt, or, Siberian felts, armyaki39 made from camel wool and paper fabrics called dubs and calico,40 and other goods.

The rock people exchanged most of the previously mentioned goods for their yuft skins,41 iron traps, axes, knives and other iron items, also salt and flour.

This information was collected by myself on the rock people or the yasak peasants, who inhabit the high and impregnable mountains of Southern Siberia. The rock people can be likened to the residents of the Alpine mountains, and maybe, in addition, are more superior with their strong bodies, simplicity of the customs and greater hospitable, which is all the more rare now among common peoples in all places, except for in Russia and Siberia.

Also known as Pechi, known today as Barlyq

A two-wheeled cart, more often spelled as “Таратайка”

Small range, about 150 kilometers in length, within the larger Altai Mountain system

Likely a reference to the side that the sun shines on during the afternoon

Actually Kazakhs, or people that would be called Kazakhs today. Up until Soviet times the people of modern day Kazakhstan were called Kyrgyz, or Kyrgyz-Kaisaks

A species of deciduous conifers

“Главную массу первого из них составляет гранит, глинистой сланец и сланцоватой известковой камень с кварцовыми прожилками, a второго гранит и зеленоватой трап”

“своевольство”

See the explanation on the "chuds" in the introduction in part one

Potassium nitrate. Can be used both as fertilizer and for gunpowder

“увлеченные склонностью пустынножительства”

See part one

The word “Siberia” is Turkic in origin

See part one, in reference to petroglyphs and mines made by the "chuds"

“В 15 верстах от Верх-Бухтарминской течет шумная речка Соврасовка и Листвяжный хребет отклонился к полудню”

“В ней находится 16 дворов жителей, каменщиков. Сия деревня примечательна тем, что отсюда река Белая, поворачивая наполдень”

Today named as Bekalka

Щебенюха, from “щебнюха”, meaning “rubble

See part one for explanation on the rock people and their unique status within the Russian Empire

Governorate, similar administratively to a province

Equivalent to a district

District level judicial-administrative body used throughout the Russian Empire, from 1775-1862

Located further down the Irtysh River from the Bukhtarminskaya fortress. Today known as Semey

Volost is an administrative unit, similar to a district or a township, or a raion in modern day Russia

This likely means one taxable person per every 300 rock people

In other words, they went from the modern day territory of Altai Krai and Altai Republic in Russia, south into what is today Kazakhstan

Likely a title related to the Qing Dynasty. I could find anything in English explaining this term, and search results in Russian were both few and very old

On the Bukhtarma River, directly north of Lake Markakol

Local representative of the Qing state

Khovdo, in western Mongolia, to the east-southeast of Chingistai

“Bogdo Khan” means “Holy Khan (ruler)”, the term Mongolians called the Qing Emperor

Buckwheat, also known as grechka in Russia

This was likely a punishment for those who did not properly care for state property

Catherine the Great

“своевольной жизни”

“Китайки”

China exported tea leaves in bulk, pressed into solid bricks

“канчи, род гарнитуру, канфы, подобные атласу, и фанзы очень низкой доброты”

“Армяки", caftan made from thick wool

“бязь” – A type of textile made from cotton, originally from India

Also known as “Russian leather”