Chuguchak - Andrei Putinstev, 1811

Translation of an intelligence report on the Chinese frontier city of Chuguchak

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of an excerpt from “The Daily Notes of the Translator Putinstev, from his Journey from the Bukhtarma Fortress to the Chinese City of Kuldja and back in 1811 (Дневные записки переводчика Путинцева, в проезд его от Бухтарминской крепости до китайского города Кульжи и обратно в 1811 году). The excerpt focuses on Putinstev’s observations of the city of Chuguchak, known today as Tacheng in the Chinese province of Xinjiang.

Andrei Putinstev was born in 1780. He worked as a cartographer mapping the region south of Omsk, and later served as a customs official at the Bukhtarma fortress. Both Omsk and Bukhtarma were major Russian fortresses on the Irtysh River, and guarded Russia’s south Siberian frontier. For more on the Bukhtarma fortress, see my translation of Grigory Spassky’s journey (part 1) up the Irtysh and through the southern Altai Mountains. The official purpose of Putinstev’s journey was to learn of what commercial opportunities existed in the northwestern frontier cities of the Qing Empire.

Puntistev’s notes very much reads like a intelligence report, as they detail not only Chuguchak’s commercial affairs, but also its military infrastructure, agriculture, and status of local nomadic peoples. This is made especially obvious by Putinstev’s observations of Chuguchak’s walls and that the Mongolian Ulyut tribes have a “special plan”, as indicated by how they manage their cattle herds. Such information obviously has no commercial value, and would only military and political purposes.

It’s worthy noting that espionage is often conducted under very banal, almost obvious ways. States often used merchants as intelligence agents, for example, the British Raj often used the Indian commercial diaspora as source of information on what was going on in Central Asia and elsewhere beyond the frontiers of India. Anyone who has read the novel “Kim” by Rudyard Kipling will be familiar with this. Russia in particular has always maintained a very active information collection apparatus. As Edward Luttwak points out, the Russian state and society as a whole, both historically and currently, is oriented towards information collection for intelligence purposes, and that this is a sphere that Russia uniquely excels in. And as can be seen in the text, a merchant or customs official can recon a city’s defenses and the disposition of local forces just as easily as anyone else can.

This should be read in the context of understanding Russia’s long standing ambitions not only to open up new markets in Asia, especially in China, but also to potentially conquer the territory that would later be known as Xinjiang (Zungaria and Chinese Turkestan). For various reasons Russia always hesitated in carrying out the later, but it did gradually secure greater and greater commercial access to Xinjiang over time. Initially Russia was only allowed to trade with China on the Trans-Baikal - Mongolian frontier on a limited basis, as stipulated by the Treaties of Nerchinsk in 1689 and Kyakhta in 1727.

The Qing Dynasty was extremely cautious of all foreign influence into China, including by foreign merchants, and as a result Beijing attempted to hermetically seal China off from the outside world. This was not done for no good reason either. Under the Qing, the oasis cities of the Tarim Basin were permanently unsettled due to commercial ties they had with Kokand in the Fergana Valley. British trade was even more destabilizing. Not only was opium exported into China which caused mass addiction, but missionaries followed the merchants. The coming of Christianity completely upset China on the ideological level and directly led to Taiping Rebellion from 1850-1864, which killed nearly 30 million people and nearly resulted in the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty itself. Other East Asian countries followed the Qing in isolating themselves from European influences with greater success. Tokugawa Japan enacted the “Sakoku” policy, which not only forbid foreigners from traveling to Japan, but even barred Japanese who traveled abroad from returning under pain of death.

Russia eventually gained commercial access to Chuguchak and Kuldja in 1851 with the Treaty of Kuldja. Later in 1864 with the Treaty of Tarbagatai (the Mongolian name for Chuhuchak), Russia annexed the territories of modern day eastern Kazakhstan, including Lake Zaisan, Semireche and the Chu Valley from the Qing. As a result of this treaty, Chuguchak became located almost immediately on the border. The modern Kazakh-Chinese border adheres to the border created in 1864. In 1881 with the Treaty of Saint Petersburg, Russia gained expanded commercial access throughout Xinjiang, as well as the right to establish consulates in various cities, which became centers of Russian espionage against China.

One last thing to note, Puntinstev notes the population of Chuguchak was largely made up of convicts exiled there from the interior of China, and Mongolian military forces. Chinese empires had long used criminals to colonize its distant northwestern frontiers. They were primarily used as agriculturalists, creating a stable and local source of food for Chinese administrative and military personnel. This method is still used today, most notably by the Bingtuan, a paramilitary force created under Mao to garrison Xinjiang. Initially the Bingtuan consisted of soldier-farmers but has expanded into managing other key sectors of Xinjiang’s economy following market liberalization.

The presence of Mongolian peoples is a result of the Qing Dynasty (founded by the semi-nomadic Manchus) using the Mongolians to conquer much of their empire outside of China proper. During the Qing’s early history, the eastern Mongolian tribes were subdued and used to conquer the western Mongols, also known as the Zungars, who were based in the region that is now known as Zungaria, or the portion of Xinjiang north of the Tianshan Mountains. This struggled played out from the mid-17th century until 1756 when the Zungars were finally defeated. For more on this, see “China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia” Peter Purdue.

The source for this translation can be found here. Putinstev’s travel notes were originally published by Grigory Ivanovitch Spassky in “Sibirsky Vestnik”, part 7, 1819. This original text in its entirety can be found here. It can be found on pages 29-96 of part 7, or pages 262-329 within the e-book/PDF. I plan to translate the full text at some point in the future.

Chuguchak

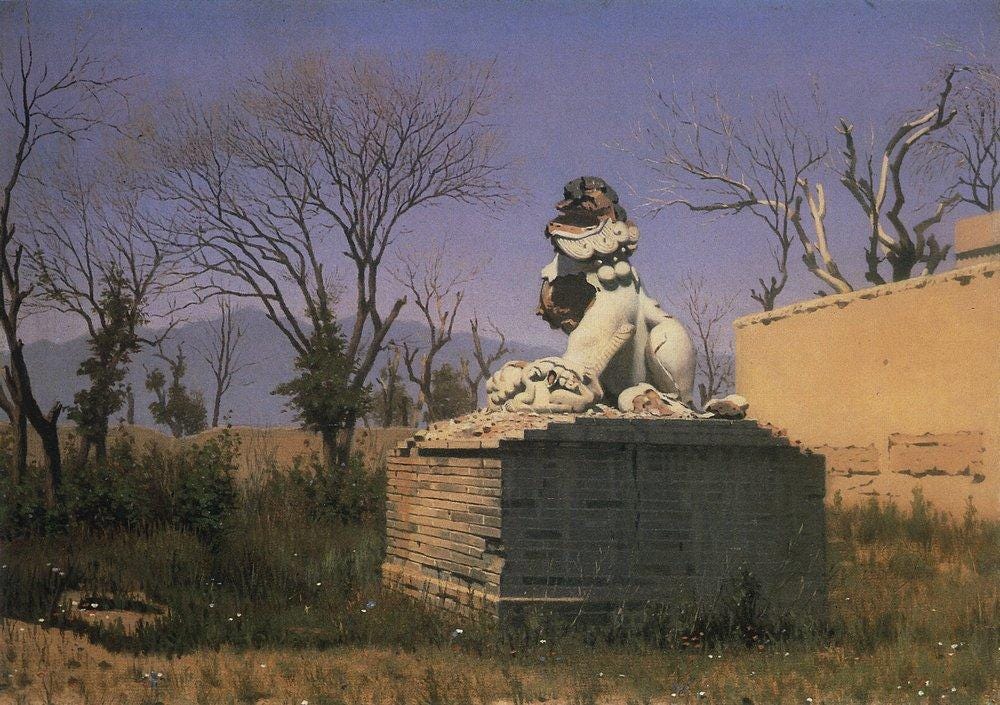

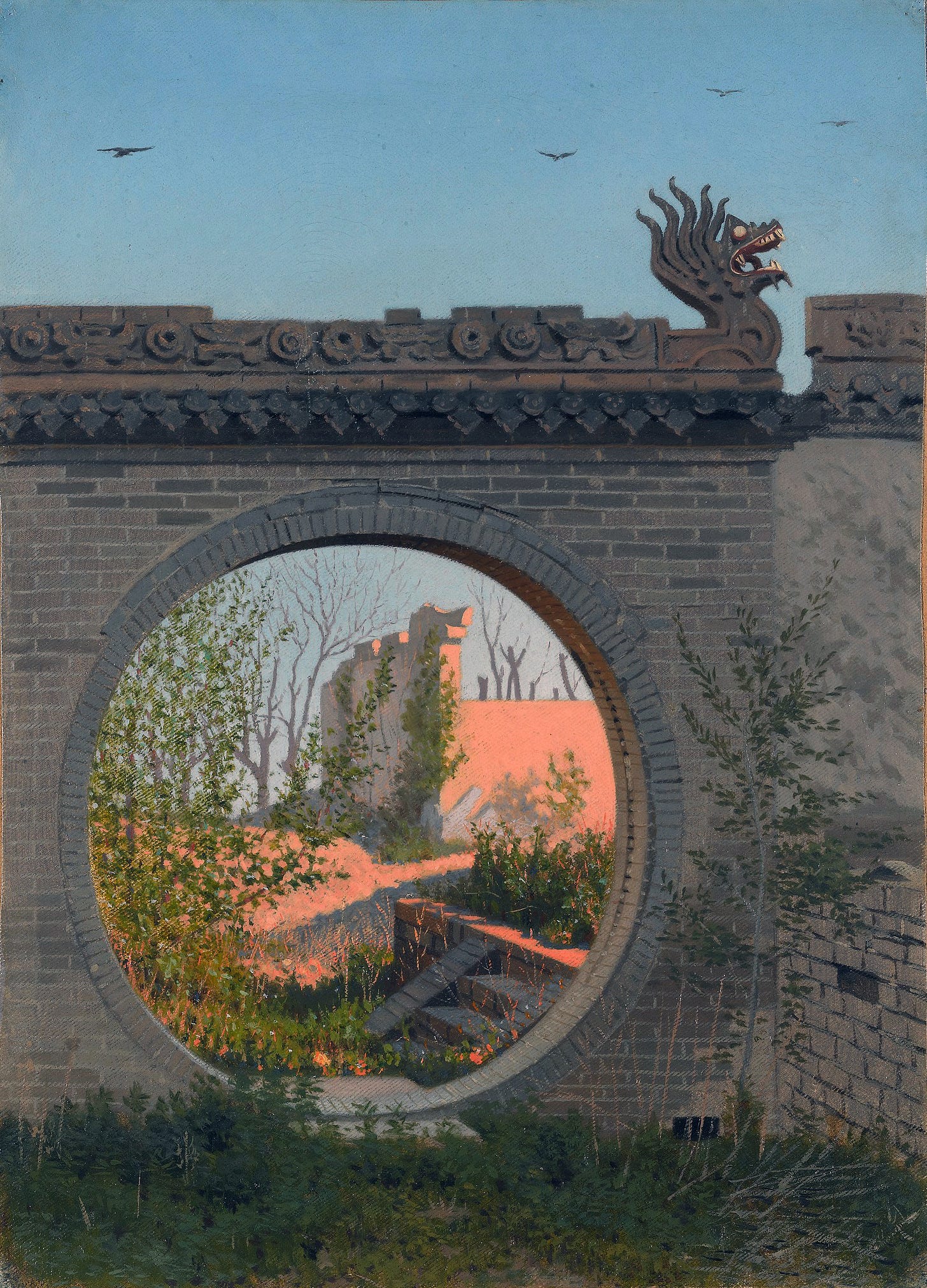

Chuguchak is one of the several Chinese cities on the frontier. It is surrounded by a four-sided stone wall, which has a length of 150 sazhens,1 located at its corners are towers with four sides that are 5 sazhens in height. In each tower on the two outer sides and on one inner side there are square windows with paper screens and covered by wooden shutters. Located on the other inner side of each tower is a large door for entry to the tower. These same towers are built above gates that serve as the entrance to the city and the exit. All of these towers and walls are made from unfired clay bricks, which have been made white on the outside. The wall’s outer slope is 2.5 sazhens high. At half of its height there are drainage ramps for the water coming from the inner parts of the fortification. Around the wall in front there is a small canal, in which water from two small rivers is funneled into, and this same city also stands above these rivers. Near the city wall on both the inner and outer sides grow willow trees, planted there on purpose; and located on the western and eastern sides adjacent to the wall are small villages and suburbs.

In the city of Chuguchak there are up to 600 homes, not excluding the barracks built for local military people. A large part of the residents of this village are temporary, sent from different Chinese cities to work in various trades, such as: merchants, craftsman and farmers; and the permanent residents there are almost entirely exiled convicts from the interior of China, working on state farms.2 Merchants in large part conduct trade with Chinese subjects: with Kalmyks, Torghuts and Ulyuts. Both of the last two peoples are also Kalmyks.3 The Torghuts are Kalmyks who fled to China from our Volga Steppes,4 and the Ulyuts are the oldest inhabitants of the local country.5 They are all generally nomadic6 and belong to the military estate;7 but the Chinese authorities, apparently, do not have a lot of confidence in them: inorder to ensure they remain on guard at the frontier, the Chinese send 1500 people from Kuldja8 to them annually.

Residents of Chuguchak, in addition to local peoples around them, have trade relations with the interior Chinese cities of Khobdo9 and Urumchi.10 From Chuguchak to the first takes 20 days travelling on a bull or a horse with a heavy cart, and to the other takes 12 days. At Khobdo trade is insignificant, but Urumchi is noted as one of the richest Chinese cities for its factories and industry. Residents of Chuguchak are able to receive the best goods from Urumchi, if only they were able to have the goods delivered there, similar to the cities of Asha, Kashgar, Khotan and Yarkent,11 whose residents also conduct important trade with Urumchi. Not only in Chuguchak, but also in Kuldja, which is quite a large city, quality tea is not sold, only so-called brick tea12 is available.

The location of Chuguchak and its surrounding areas are favorable to agriculture; wheat, millet and barely are especially abundant there, but sarachin millet almost never grows there at all, and it is delivered from Kuldja and Urumchi. Gardening is not extensive: travelers have only seen apple trees. There are many garden vegetables, more so than tobacco.

Cattle herding around Chuguchak is fairly developed, mostly among the Torghuts and Ulyuts. The Torghuts are very willing to exchange cattle for silver, while the Ulyuts are trying to breed more cattle and increase the size of their herds. Mr. Putinstev concludes from this, that the Ulyuts have some sort of special plans.

<…>

On 25th July, early in the morning, an interpreter was sent to Mr. Putinstev with the orders that he and everyone belonging to his caravan must immediately go with him to the chancery, which they did. Upon arrival there the local governor ordered 4 people from his subordinates to lead them out of the city. This news surprised the travelers, and no matter how much they tried to find out the reason for this, there was no answer to this and those escorting them knew nothing. There was nothing to be done, except only to obey the order.

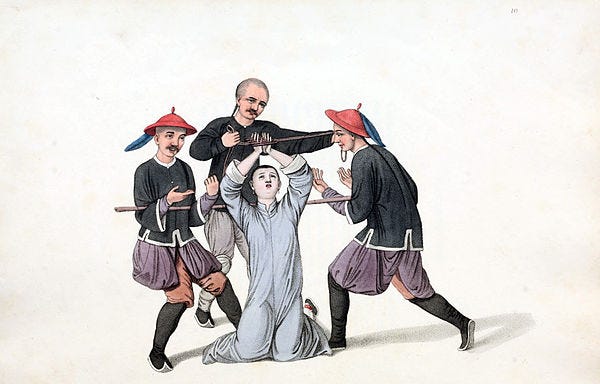

Upon arrival to the designated place, they saw a large grouping of people, a lined row of service people13 and one person being carried on a two-wheeled cart, with his hands tied behind his back and being escorted by 12 men with drawn swords. Before him went three members of the chancery, one after another, with another 12 commoners: the one in the middle had some kind of sign in his hands, like staff that was covered by a handle which had a Chinese inscription. The person being transported was a prisoner, being taken to his execution.

Two of the members accompanying him went into an already sent up tent and placed the previously mentioned sign on the table, and when the prisoner was brought the place execution place, some of the officials approached our travelers and announced to them the following through an interpreter: “his Majesty the Bogda-Khan14 commanded us (showing the prisoner and the horse standing there) to cut off his head for the theft of this horse; such in the justice of the Bodga-Khan and severity of the laws, for whenever you are in within its boundaries, not only our loyal subjects, but whoever it is, similar crimes will be punished without any respect”. During this time the prisoner fell to his knees; his eyes were covered by a thin string, the end of which were held by two executioners, a third held in his hands a sword, with which he used to strike the prisoner across his neck; but he could not off his head in one strike, then two of his comrades, threw him on to the ground and cut his head off with a knife. This unfortunate man had lived no more than 18 years.

On the nights of the 28th and 29th, workers belonging to the caravan caught a Kalmyk who had intent to steal horses that were usually always tied up at night and that the travelers had ordered to be strictly guarded. The guards should have been located with the horses included two high-ranking officials, one from Manchuria, another from Chauar,15 and 7 commoners, but of these, except for two Kalmyks, none of them were there that night. The next morning, very early, they arrived together with an interpreter and requested that what had happened not be brought to the chancery’s attention, and to give them the thief for punishment. Mr. Putinstev, called upon the Tashkentis16 with him, told them the official’s request. They agreed and handed over the Kalmyk, and in their presence he was hit 50 times with the whip as punishment.

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.13 meters or 7 feet

See “China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia”, chapter 9 “Land Settlement and Military Colonies” for more on this.

Nomadic ethnonyms are often times are just names of tribal groupings and subgroupings

The Kalmyks migrated from Zungaria to the Volga Steppes in the early 1600’s, and eventually came under Russian rule. Later in the 1770’s, some the Kalmyks, dissatisfied under Russian rule, migrated back to Zungaria and submitted to the Qing. See “Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads 1600–1771” by Michael Khodarkovsky for more on this

Ulyut is possibly a bastardized way of spelling Oirat in older Russian texts, but I am not familiar with this subject in Russian language literature enough to say for certain

Not all “nomads” nomadized. Often cities were built and sometimes nomadic populations engaged in agriculture

“к сословию”. The Qing Empire was a multiethnic empire, and its different peoples were used in different capacities. Mongols were typically enrolled in the “banner system” and primarily served in a military role

Today known as Yining, in the Ili valley

Modern Khovd, today in western Mongolia (then a part of the Qing Empire)

To the southeast of Chuguchak. Urumchi is current capital of Xinjiang

Cities in the Tarim Basin, south of Chuguchak beyond the Tianshan Mountains. Also a part of modern Xinjiang

The Qing Dynasty at this time mostly exported tea leaves that were compressed into bricks, and sold them in bulk

Those who serve the state in some capacity

Mongolians would refer to the Qing (Manchu) emperor with this title, meaning “Holy” or “Godly” Khan. At the time, the Qing Dynasty was ruled by the Jiaqing Emperor

“другой из чауаров”. Its unclear to me where this is. Possibly referring to the Choros, another Mongolian tribal grouping

From the oasis city of Tashkent in what would become Russian Central Asia. Much of the commerce and management of caravans was done by people from the city states of Trans-Oxiana. At the time of writing, Tashkent was a part of the Kokand Khanate, based in the Fergana Valley