Russia's Withdrawal From the Ili River Valley in 1881 - Vsemirnaya Illyustratsiya, 1882 & Ivan Poklevsky-Kozell, 1885

Translations on Russia's retreat from the Ili Valley, the resettlement of the Ili's population & strategic implications

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below are two translations on the end of Russia’s occupation of the Ili Valley and the territory’s return to China’s Qing Dynasty.

The first discusses the handover itself and was published by Всемирная Иллюстрация, 1882, № 686 (All-World Illustration). I could not exactly located the original, but it is likely somewhere here. The source for the translation can be found here. All-World Illustration was a weekly journal containing art and articles. It was founded by a Prussian, Hermann Hoppe, and became Russia’s most popular illustrated journal with circulation reaching 10,000. It ran from 1869 to 1898.

The second is an excerpt from a text was written several years after the return of Ili to the Qing, and discusses the region’s economic, military and strategic potential. The original text is titled “Новый торговый путь от Иртыша в Верный и Кульджу и исследование реки Или на пароходе «Колпаковский».” (New Trade Routes from the Irtysh to Verny and Kuldja and Research of the River Ili on the steamship “Koplakovsky”), published in 1885 by Ivan Ivanovich Poklevskii-Kozell. The original text can be found here. The source of the translation can be found here.

Ivan Ivanovich Poklevskii-Kozell was Polish-Russian military engineer and born in 1837 in modern day Belarus. He as involved in the Polish Uprising against the Russian Empire in 1863 and ended up in emigration in France, where he later served in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. He returned to Russian controled Poland in 1872. Despite promises of amnesty, he was arrested upon his return, exiled to Central Asia, and enrolled in the Semireche Cossack force. In Russian Turkestan he had an illustrious career where he led the construction of Verny, modern day Almaty (Kazakhstan’s largest city). He was later tasked with developing industry in Ili while it was under Russian occupation, as well a being considered the founder of Zharkent. Later he worked in Russia’s Trans-Caspian Oblast (modern day Turkmenistan).

A few notes on the historical and geographic context of the texts. Russia conquered the “Semireche” region in the 1850’s. The word “Semireche” is Russian, meaning “Seven Rivers”, a reference to the seven main rivers that flow into Lake Balkhash. The region is also known as “Zhetysu”, a Turkic word which means the same thing. This region historically was very geopolitically important as it was a like a giant oasis on the steppes. Several nomadic empires were based here, including the Saka, Western Turkic Khaganate, Karluks, Karakhanids, and Kara Khitan (or Western Liao Dynasty). Prior to the Russians, the region was occupied by the Big Horde of the Kazakhs.

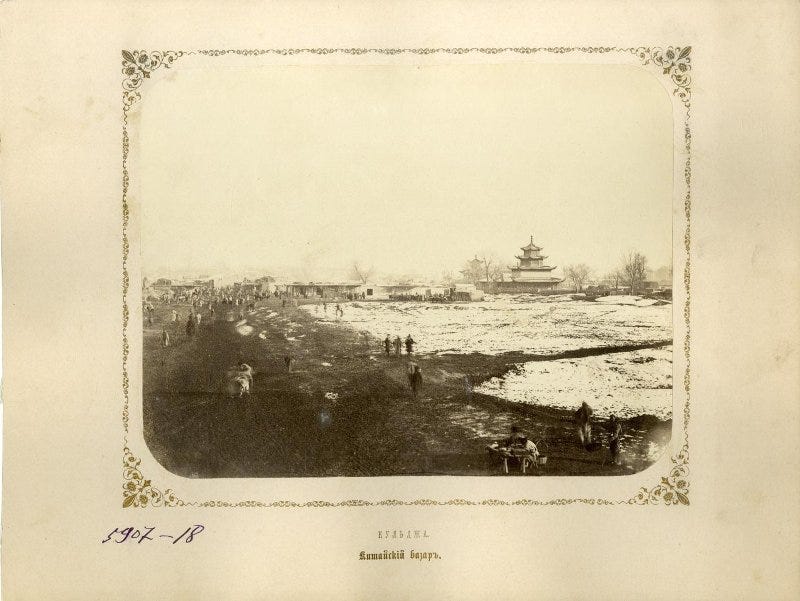

Of the seven rivers that make up Semireche, the Ili is the largest. While Russia controlled the lower half, the upper half remained within China’s Qing Dynasty. While Semireche is largely steppe, in its upper reaches inside of China the Ili flows through a large mountain valley carved out of the Tianshan mountains. The main city is today known as Yining, or Ili City, but in the past it was called Kuldja (sometimes spelled as Guldja). As Poklevskii-Kozell mentions below, the Russian-Chinese border at the Ili Valley is nothing but an arbitrary line drawn in the sand.

Today, the Kazakh city of Khogos on the Kazakh-Chinese border at the Ili Valley is one of the most important dry ports on China’s new Silk Road, where cargo is transferred from the Chinese railway system to the Russian system (the USSR used a smaller rail gauge as it would slow down the logistics of any invading army).

Russia came to occupy the Ili Valley in 1871 due to the Dungan Revolt, a massive Muslim uprising which raged across the entire northwest of the Qing Dynasty. Ili came under the control of the Sultanate of Ili, which began raiding Russian territory. In response the Russians invaded and occupied the region “on behalf of the Qing”, and used it as a buffer between the rampaging Muslims in the Tarim Basin and their own Central Asian territories. Eventually a Qing force reconquered Xinjiang. The Russians feared that the Qing would be able to easily defeat and dislodge its forces from Ili, so they peacefully evacuated and gave the region back to China under the terms of of Treaty of Saint Petersburg. Thus, the Ili Valley is the one and only place in Central Asia that Russia retreated from (not including the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan).

For more on the Dungan Revolt, see “Holy War in China” by Kim Ho-dong. For more on why Russia withdrew from Ili, see “The Russian General Staff and Asia, 1860-1917” by Alex Marshall. The Soviet Union also controlled Ili for some time. For more on this, see my book review on The Russian Conquest of Central Asia" by Alexander Morrison and “Stalin and the Struggle for Supremacy in Eurasia” by Alfred J. Rieber.

It is also interesting to note how the Russian authors here describe the Chinese as being corrupt and cruel, which is very similar to how Westerners often write about Russians, both historically and today. If we are to use the standards of Western polemics against Russia, these Russian accusations against China were probably at least half true. But it also should be noted that the Chinese were likely justified in the their actions. Anyone remaining in Ili after Russia’s evacuation could be spies that were left behind by the Russians, and the Kyrgyz who “accidentally” wandered into Chinese territory could be scouts. It is impossible to say for sure, especially so from the standpoint of the local Qing authorities who were tasked with guarding the frontier. Why should they accept of the risks of Russian espionage against them? After all, Russia was nothing but aggressive towards China during this period, not only did they attempt to seize Ili, but the Far Eastern regions were taken from China in the early 1860’s and Russia was constantly meddling in Mongolia.

Also interesting to note that the fears of China’s future ambitions towards Russia and Central Asia are not at all new. But just like such predictions in the past, similar predictions today will be proven to be unfounded I believe. Maybe sometime soon I will write an article explaining why I think Russia and the post-Soviet Central Asia states have little to fear from China, at least in the immediate future.

The Handover of Kuldja to the Chinese

Передача Кульджи китайцам // Всемирная иллюстрация, 1882, № 686.

As soon as the agreement to handover Kuldja to the Chinese was ratified, the head commander of the Semireche oblast ordered its contexts announced to the local residents, and asked who whom among them wished to be resettled in Russia and who would stay under Chinese rule. With this purpose, on the 16th of July last year (1881), Kuldja’s leading mullahs, biys,1 kazis,2 and other representatives of the Dungan3 and Taranchi4 population were assembled, and Major-General Fride,5 the head commissioner of the handover, announced to them that Kuldja would soon go back to the Chinese, but that any of the residents who desired to remain under Russian rule will be given land, which had already been partially surveyed and found suitable for settlement. Additionally, he promised that those in need would be given provisions.

This speech deeply touched those present, and one from among the Taranchi elders, in few, but emotional words expressed gratitude on behalf of the population: “we do not need anything from the White Tsar, just let Him provide us with a small piece of land – we will be very grateful to Him for that” he said. The other representatives of the Dungans and Taranchis also confirmed this, adding that nearly none of the tribes wished to remain under Chinese rule.

Their course of action was understandable. Not only does the local population wish to be resettled, who are well acquitted with Chinese customs and do not trust the Chinese promises of amnesty, but even many Chinese plan to resettle within our territory due to the danger of the officials of the Bodgakhan6 using some pretext to take away the property that they acquired during the time their country was under Russian rule.

It cannot be said that these fears were baseless. Before the Chinese had managed to accept Kuldja back under their control, Erkebun,7 who had been appointed to accept the territory, began to demand the extradition of some wealthy Chinese from us, despite that such claims were in direct contradiction to the terms of the treaty with China. Of course, his request was rejected, but this attempt serves as evidence that the promises of the Chinese authorities cannot be relied upon, especially since other information confirms the bad faith manner with which the Chinese are executing the terms of the treaty.

Some of our merchants were not allowed to enter certain places that Russians were supposed to be allowed to trade in; in other places caravans were detained – and some Kyrgyz, who passed through Chinese territory by mistake, had parts of their herds confiscated and suffered beatings, and some were seriously injured.

All of these facts, of course, were not unknown to the population of Kuldja, and that is why nearly everyone without exception chose to resettle within Russian territory. The Chinese themselves, seeing this, sent people from their inner provinces of their empire to our frontier to be settled, those who were too well acquainted with the yoke of the Mandarins.8

Unfortunately, antagonisms between the Dungans and the Chinese did not end under Russian control, and recently they reemerged with a new force: several Chinese families in the city itself were robbed, with one women being wounded by a bullet; also on the roads small gangs of robbers appeared. Under favorable circumstances these gangs can massively increase in size, as was the case with the Dungan uprising.

These are the conditions with which the handover of Kuldja occurred. Apparently, it is difficult to count on lasting peace if the Chinese do not change their system of rule, for which, it seems, there is little to hope for.

Kuldja: The Pearl of Our Steppes

И. И. Поклевский-Козелл. Новый торговый путь от Иртыша в Верный и Кульджу и исследование реки Или на пароходе «Колпаковский». — СПб., 1885.

Speaking of Semireche, one cannot fail to mention Kuldja, which in essence, has nothing separating it from Semireche except for a recently delineated border along a completely flat place in the Ili valley. Kuldja – this was the pearl of our steppes. A wonderful climate, the most fertile soil, the richest deposits of coal and other minerals; wonderfully constructed irrigation across the entire territory, magnificent gardens, excellently cultivated soil, wonderful vegetable and rice fields, and with a population that is sober, hardworking, and very well acquitted with agriculture, managing irrigation and mining. Without exaggeration it can be said, that across all of Russia there is no corner as perfectly suited to become an industrial center as Ili, it is as if it was created by nature for such a purpose.

As an example of the region’s mineral wealth, I point to the coal mines that belong to me personally. In one mine I had on the right bank of the Ili, the layer of coal was 30 arshins9 deep and there were also deposits of high quality iron and excellent fire resistant clay. In another, on the left bank of the Ili there were coal and iron outcrops located on a steep hill 200 sazhens10 from the river and were placed in such a way that a furnace could be built below, with the ores and coal lowed straight down into the furnace and the finished iron would be then lowered on to a barge waiting on the river. Additionally, with a small amount of money this place could be possible to build a water powered turbine with the power of several horses.

Currently the Chinese own this wonderful valley and can concentrate supplies and military forces there, which will constantly be a threat to us. The handover of Kuldja made the creation of good communications between Semireche and Russia an urgent necessity. Although it is commonly said that the Chinese have remained very motionless, all the same, this assumption should not be relied upon too much. I think that they will not hesitate to very quickly turn Kuldja into a strong military settlement. With improved rifles and cannons, and a sufficient number of Prussian instructors, the Chinese can be transformed from being funny to scary. They have a very large population and it cannot be said that the Mandarins value the heads of their soldiers. While we were separated by the deserts the Chinese were not scary, because no army could cross the massive steppes from Hami to Suzhei.11 A few battalions of infantry and a few sotny12 of Cossacks would be all that it takes to defend our frontier here. But after the Chinese occupied Kashgar and after Kuldja was returned to them, we had before us not an insignificant Middle Asian khanate, but massive China, and we stood eye to eye on a single road, along which from time immemorial great migrations of people took place. The Ili and Chu – these are the two great roads along which that all Asian conquerors traveled.

To our happiness and to the honor of the local Russian administration, the entire Taranchi and Dungan population of Kuldja was resettled in Semireche. This weakened the Chinese for some time and strengthened us. As far as I know, the movement of Kuldja’s Muslims into our territory is unprecedented in Russia’s history, no one or hardly anyone has noted this significant fact. The entire population, despite the benefits provided to them by the Chinese and offers of silver and cattle, left their most prefect country, the graves of their ancestors, their holy temples and followed the Russians to a barren desert steppe. They destroyed their old homes, so that Kuldja today after being returned to the Chinese apparently is nothing but rows of ruins. The English and French, who do not say particularly flattering things about Russians, and who use to the word Cossack almost as a synonym for barbarism, are constantly busy with pacifying various uprisings in Asia, Africa, all while the entire population of Kuldja followed behind our Cossacks and the warlike population of Merv13 peacefully surrendered to our Cossacks. Anyone who has lived in Middle Asia cannot be anything but convinced that the influence Russia has upon these regions is huge; Russia holds the Asians more so with its moral force than by its armed force.

Elected judges among the Kazakhs

Islamic legal scholars and judges

Chinese Muslims. Known in China was Huis

Agriculturalists from the Tarim Basin who were resettled in the Ili valley by the Zungars and later Qing. They would be considered Uyghurs today

Alexey Yakovlevich Friede

Mongolian term for the Manchu emperor of the Qing Dynasty

From what I can find, this was a Qing regimental commander

Reference to Chinese officials

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 arshin = 71.12 cm/2.33 feet

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.1336 m/7 feet

Hami is the eastern most city on the Silk Road beyond China. I do not know where Suzhei is, this is presumably an old name that is no longer used

“hundreds”. Cossacks were organized in units of 100

A large oasis in Turkmenistan. Merv was taken by Russian in 1884

Wonderful pictures, breathtaking landscapes!

It would be great if some of these articles were compiled & published in book form. With pictures. And maps.