"The Russian Conquest of Central Asia" by Alexander Morrison: Book Review & Analysis

Ambitious Men on the Frontier, Contested Sovereignty, Steppe Fortresses, Xinjiang - Exploring Russia's Conquest of Middle Asia

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

This review is a follow up to my Twitter thread on Alexander Morrison’s book “The Russian Conquest of Central Asia: A Study in Imperial Expansion, 1814-1914.” My thread outlines Morrison’s book with excerpts. My thread can be read here, but it is not at all necessary to read the thread before this review. The book will be summarized below.

Introduction

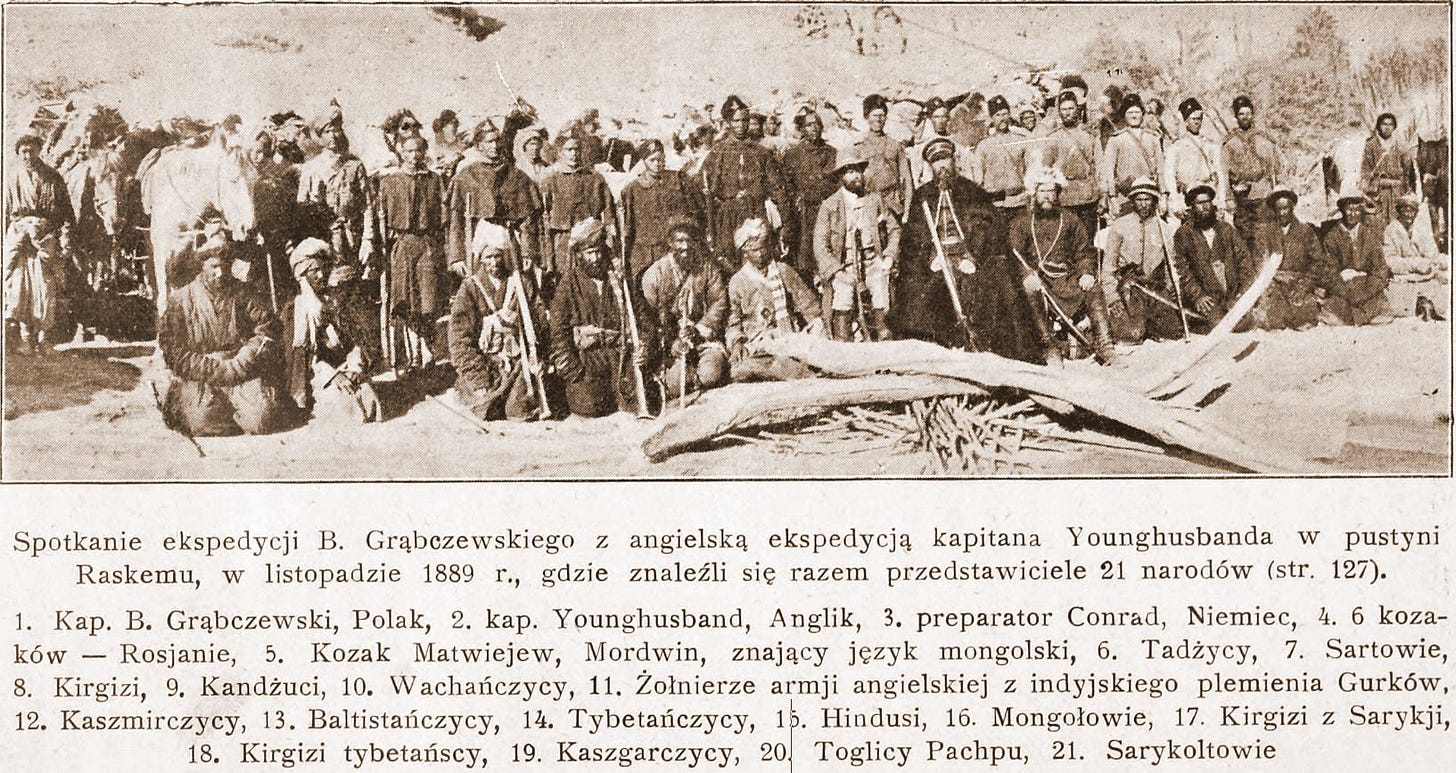

The history of Russia’s conquest of Central Asia has remained largely unknown and unexplored by English language historians, despite the enormous latent interest that exists for the topic. For the English speaking world, their awareness of Russia’s imperial expansion into Central Asia is mostly a derivative of the “Great Game”, the 19th century competition between Britain and Russia for empire in Central Eurasia. While the history of Britain’s expansion into India’s northwestern frontier, Afghanistan, Persia, Tibet, and Chinese Turkestan are all well known, in large part thanks to Peter Hopkirk’s wonderful books, the movements of Britain’s imperial rival are almost entirely clouded in mystery. More than simply that, the terrain itself that Russia conquered is terra incognito for most. While many have heard of places like the Fergana Valley, Samarkand , or the Pamirs, hardly anyone knows anything about these places, their geography, the ethnography and history of local peoples. Readers of Hopkirk’s “The Great Game” are left at a loss in regards to Russia’s movements and affairs beyond the Hindu Kush, just as much as the British in Indian would have been at the time. This sense of mystery, of the looming Russian titan gradually encroaching on the frontiers of the Raj, certainly adds to the allure of the book, but it also limits our historical knowledge considerably.

Thanks to Alexander Morrison’s amazing work, the veil of mystery surrounding Russia’s expansion into Central Asia has been decisively penetrated and conquered. “The Russian Conquest of Central Asia: A Study in Imperial Expansion, 1814-1914” is the best English language text on the subject (as far as I know). The text is very comprehensive and detailed, relying largely upon Russian language primary sources including memoirs of soldiers and generals, internal state memorandum, and private letters. Morrison captures the full scope of Russia’s expansion into Central Asia, and highlights many noteworthy elements, some of which will be further explored in this review. The text is written in an academic style, but is still very readable, and even captures the sense of adventure that must have been felt by the Russian conquerors at the time.

Morrison’s historiographical contribution is also extremely important. Many explanations exist for why Russia conquered Central Asia which are faulty, or only make sense with the benefit of hindsight. Morrison dispels these myths, while providing a thesis of his own, which will be explored further below. Additionally, the book’s biography and footnotes are extensive. This provides a particularly curious reader with a real rabbit hole to dive into.

That being said, the book does have a few flaws and shortcomings. Morrison at times does not write as clearly as he could, and at times his overly wordy prose obscures the topic at hand. Especially for military and strategic affairs, the simplistic style of Xenophon in his “Persian Expedition” is the benchmark that should be aimed for. Morrison also does not fully explain the importance of Russia’s fortified lines as well as he could. Their importance in Russia’s conquest of the steppe nomads will be explained throughout this review.

Additionally, the subject of Russia’s relations with China’s Qing Dynasty in Central Asia is almost entirely absent from the book. This is likely because Morrison chose to solely focus on what would later become “Russian Central Asia”, instead of examining the whole region holistically. Russia’s involvement in “Chinese Turkestan” and its relations with the Qing should have been examined for several reasons. Firstly, the division between Russian/Western Central Asian and Chinese/Eastern Central Asia is entirely artificial and entirely based on the division of the region by the Russian and Qing empires in the 19th century, the period of history that this book covers. Second, the Qing Dynasty and its territories were intimately involved with Russia’s conquest of Central Asia. Semireche was annexed from the Qing, the Ili Valley was temporarily occupied, and Russia very well could have annexed all of Chinese Central Asia if history had played out slightly different. Many prominent Russians, such as Nikolai Przhevalsky,1 wanted exactly this. Thirdly, western and eastern Central Asia are broadly united in culture and deeply connected through trade. The region can only be understood in its totality.

This book review will summarize Morrison’s work, examine his thesis for why Russia conquered Central Asia, place Russia’s conquest of Central Asia in the broader context of Russia’s expansion across Asia, and highlight certain noteworthy and interesting aspects of Russian imperialism.

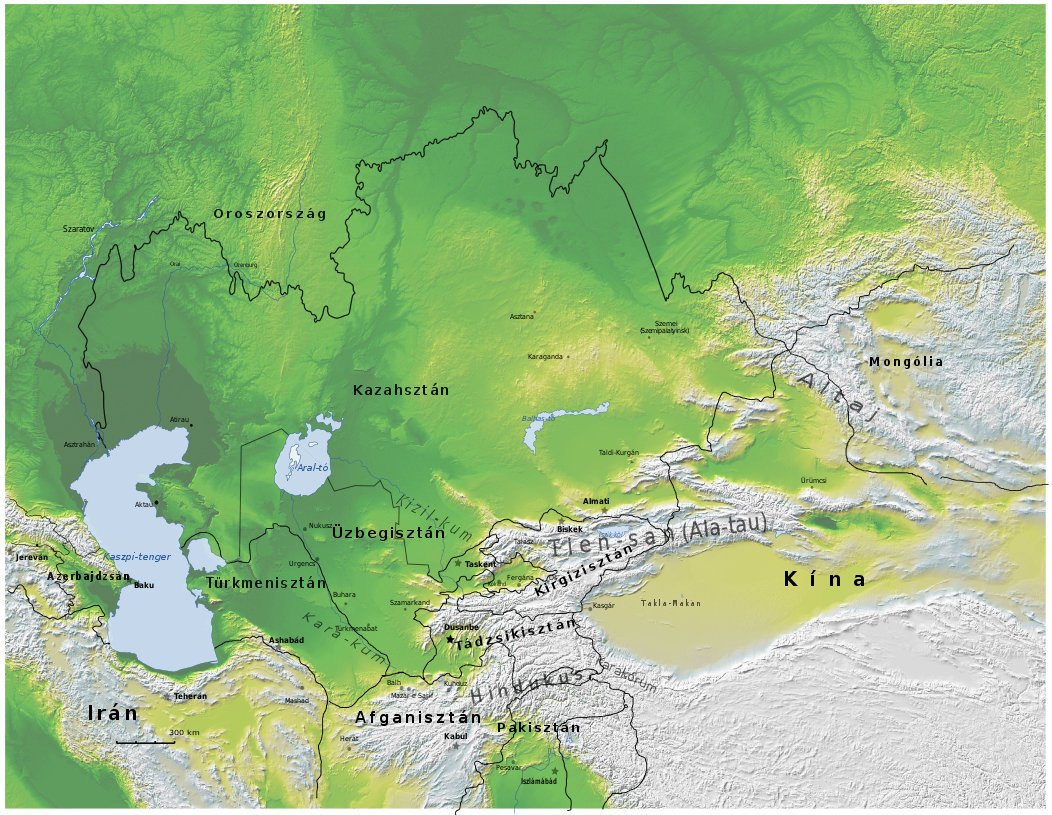

Historical Outline of Russia’s Conquest of Central Asia

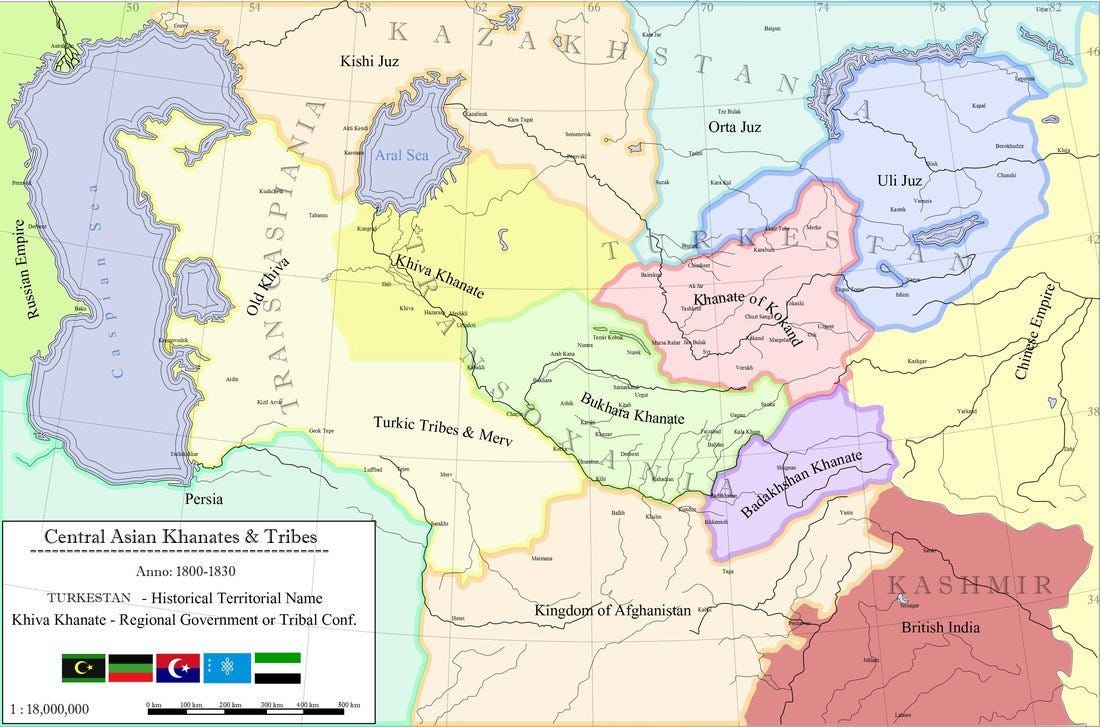

On the eve of Russia’s invasion of Central Asia the region was divided between three sedentary states, known as khanates, which also commanded significant nomadic cavalry forces as auxiliaries. These were the Kokand, Bukhara and Khiva Khanates. Most of the territories of these three states were later joined together to form the Uzbekistan Soviet Socialist Republic during the 1920’s. The Kazakh steppes were split between three nomadic hordes, also called Zhuz, which were highly fragmented internally. In the Tianshan Mountains were the Kyrgyz nomads, which were fragmented along tribal lines, with some tribes aligning with Kokand or Bukhara, and others with the Qing Dynasty. South and west of the Amu-Darya River were the nomadic Turkmen, who were also fragmented along tribal lines. Some of these Turkmen were aligned with Khiva, while others were partially sedentary and based around several oases. The Pamir Mountains were home to both Krygyz nomads and more sedentary Tajiks. These communities were either aligned with Bukhara, Kokand, the Qing Dynasty, Afghanistan, or simply autonomous. Nearly everyone in the region was a Turkic speaker, while the major cities hosted significant Iranic-speaking2 and Jewish3 minorities. The Tajiks of the Pamirs are also Iranic-speaking.

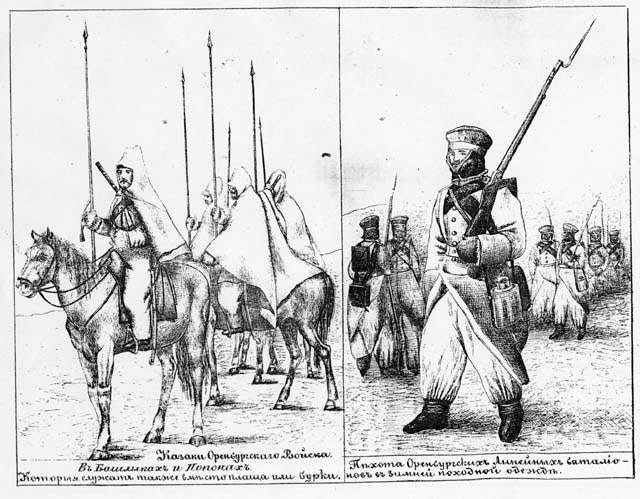

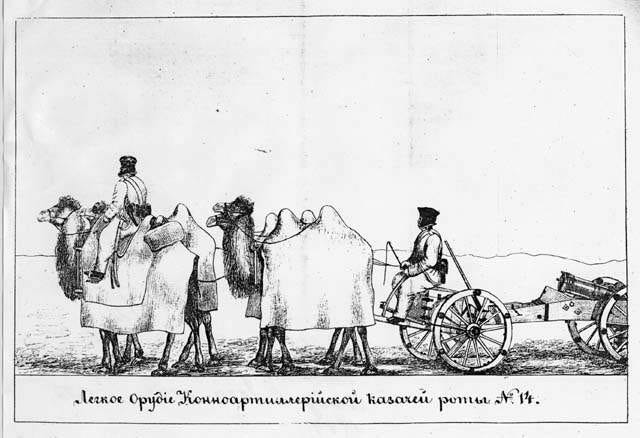

By the time Russia fully embarked upon its quest to conquer Central Asia in the 1830’s, it had already fully assimilated Western European military innovations, namely those in organization, tactics, and small arms and artillery technology. While Russia consistently lagged behind the West in terms of military modernization, its army and irregular Cossack cavalry forces easily overpowered local Central Asia forces in almost every engagement they fought. It was not necessarily that these local Central Asians were “backwards”, their armies were equipped with artillery and muskets, they knew how build fortifications and entrenchments, and the nomads fought with firearms as opposed to bow and arrows. Instead, the Central Asians were simply modernizing at an even slower pace than Russia was. In this sense, Russia’s conquest of Central Asia reflects the entire 19th century’s military history of the European world encountering the non-European world in microcosm.

The challenges Russia faced in Central Asia were not at all military in nature, but instead logistical. These logistical problems were compounded by the region’s harsh environments of arid steppes, mountains, and deserts. Almost always when Russian forces encountered local Central Asians on the field of battle, Russian arms were triumphant. It was only when Russia was already suffering from a lack of supplies that local Central Asians were able to inflict defeats upon them, such as in the steppes around Khiva, or in the depths of the Karakum desert of Turkmenistan. When Russian armies was campaigning in the sedentary, agricultural regions of Central Asia where supplies could be easily found, such as around Tashkent, the Fergana Valley, the Zerafshan Valley, and within the Khiva oasis, Russia never suffered defeat.

Russia’s first target was the Khanate of Khiva, located in the delta of Amu-Darya River, south of the Aral Sea. Khiva was also the Central Asian khanate that was located the closest to Russian supply bases on the rivers Ural and Volga. Russia first attacked Khiva in 1717 during the reign of Peter the Great. This attempt failed due to the harsh winter weather, a lack of supplies, and the hit and run tactics of Turkmen nomads who were aligned with Khiva. A second attempt was made in 1839 which also ended in failure for similar reasons. While being closest to Russia, Khiva was particular hard to conquer as it was isolated and surrounded by barren steppes and deserts inhabited by the Turkmen, who were particularly formidable warriors.

With the failure to conquer Khiva, Russia completely changed its strategy towards Central Asia. Russia temporarily abandoned its ambitions to conquer Khiva, and shifted its focus to controlling the Kazakh nomads. In order to achieve this Russia returned to its traditional approach of managing steppe nomads and drawing them into its orbit. This was done through the creation of chains of fortresses, primarily along important rivers, which served to both constrain the movement of nomads and force them into Russia’s orbit. These fortified lines were progressively expanded and eventually intersected each other, which allowed Russia to regulate the nomad’s migratory patterns and control their access to important resources, such as water and salt.

The fortified lines also served to detach the nomads from the khanates and reorient them towards Russia. The nomadic Kazakhs were aligned with the khanates primarily for trade purposes. The pastoral nomadic economy can exist in a state of autarky, but in order to obtain a variety of useful goods, as well as luxury and prestige items, trade with a sedentary society which is capable of producing such goods is necessary. As Owen Lattimore said, “It is the poor nomad who is the pure nomad.” These Russian forts as served as markets for nomads, where they could trade their animal products for Russian products, such as textiles, magnifying glasses, furniture, firearms, agricultural food supplies, and more. And of course, access to these commercial marketplaces was dependent upon political alignment. In order for the Kazakhs to trade with the Russians, they needed to respected Russian interests, which included distancing themselves from Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand.

The fortified line strategy dates as far back in Russian history as the period of medieval Muscovy and the Belogorod Line, and was instrumental in Russia’s expansion across the western Eurasian steppes from the 16th century onwards. This will be discussed in greater detail further below.

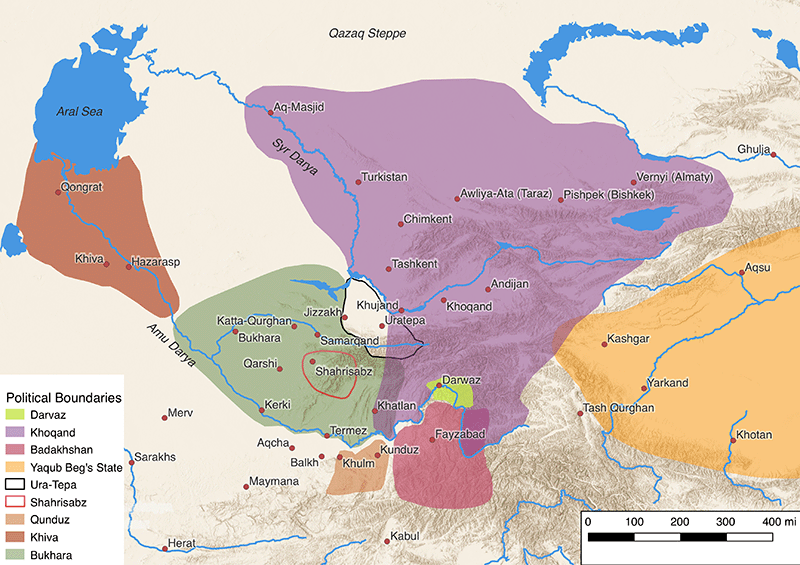

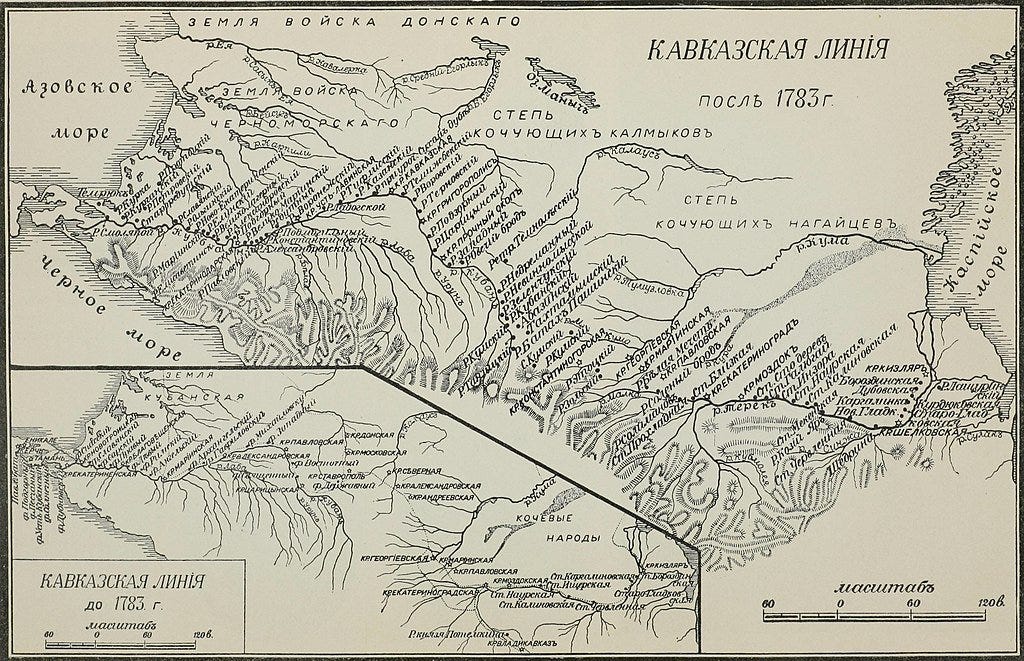

Beginning in the 1840’s, Russian penetrated into the Kazakh steppes with two separate fortified lines, both running south. The western line was supplied from Orenburg, and ran along the Syr-Darya River. The eastern line was supplied from western Siberia, and ran along the Irtysh River and the western Altai Mountains towards the Tianshan Mountains, parallel with the Zungarian Alautau. The development of these fortified lines brought Russia into direct conflict with the Khanate of Kokand, who already managed a network of fortress across the southern Kazakh steppes. Russia was essentially seeking to displace Kokand as arbiter over the Kazakhs.

The western line began with Kazalinsk near the Aral Sea, but to expand the line Russia needed conquer the Kokandi fortress of Aq Masjid (now Kyzylorda, near Baikonur) on the lower Syr-Darya River, which was taken in 1853. The eastern line was extended towards the Semireche4 region. Semireche had been home of the Kazakh Big Horde, a nominal vassal of the Qing Dynasty. The Qing handed this region peacefully to Russia in 1851, in the Treaty of Kuldja. The fortress of Verny (modern Almaty) was established in 1854, and soon after the Kokandi fortresses of Pishkek (modern Bishkek), Tokmak, and others were easily taken. The Russians then expanded their fortress line westwards along the northern face of the Tianshan. These two lines culminated and linked up with each other at Chimkent in southern Kazakhstan, which enclosed the majority of the Kazakh steppes within Russian control. The majority of Kazakhstan was effectively under Russian control.

While establishing these two lines was easy enough, supplying them was enormously expensive due to the distances involved. Russian military planners wanted to anchor the lines to secure supply base at the southern end of the lines. Tashkent and its large oasis immediately south of Chimkent was the logical choice as the southern anchor and supply base.

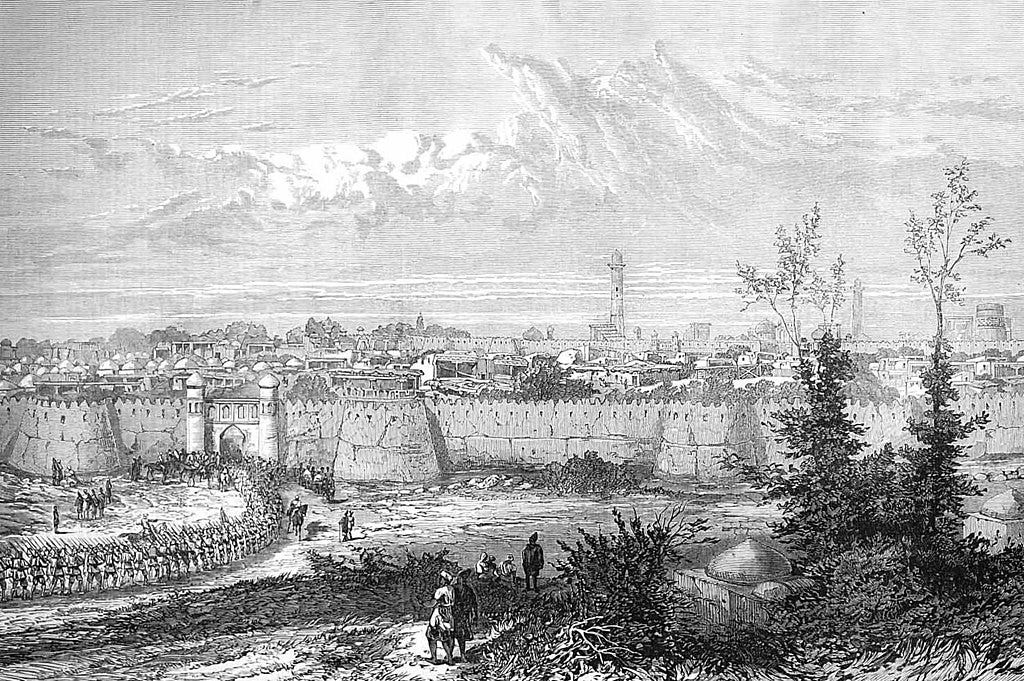

Tashkent was taken from Kokand by General Mikhail Grigoryevich Chernyaev in 1865. With the conquest of Tashkent, Russia’s conquest of Central Asia entered a new phase that would see Russia campaign throughout Central Asia’s sedentary agricultural region, and decisively defeat three khanates, one after another. The capture of Tashkent provoked Bukhara into declaring war on Russia. Not only did Bukharan armies threaten Tashkent, Russia also feared that Bukharan Imams would stir up Tashkent’s population into a jihad against it. In order to defend Tashkent, Russia was required to conquer further south and push Bukhara back.

Russia first defeated a Bukharan force immediately south of Tashkent, and then turned east to secure Tashkent’s eastern flank from Kokand in the Fergana Valley. Khujand, which controlled the entryway to the Fergana Valley, was taken, and so was Ura-Tepe, modern Istaravshan. After this Kokand made peace with Russia, and became a vassal state under the Tsar. Russia then pushed south from Tashkent towards Samarkand, the greatest city of Central Asia, located in the Zerafshan Valley. Russia took the Jizzakh pass in 1866. Peace was made with Bukhara, but was soon broken due to aggressive Imams within Bukhara that wanted war with Russia to continue. In 1868 General Petrovich von Kaufman advanced on Samarkand, and dislodged a Bukharan force that was entrenched on the Chupan-Ata heights to the northeast of the city. With the heights lost the Bukharans abandoned Samarkand, which Russia soon entered.

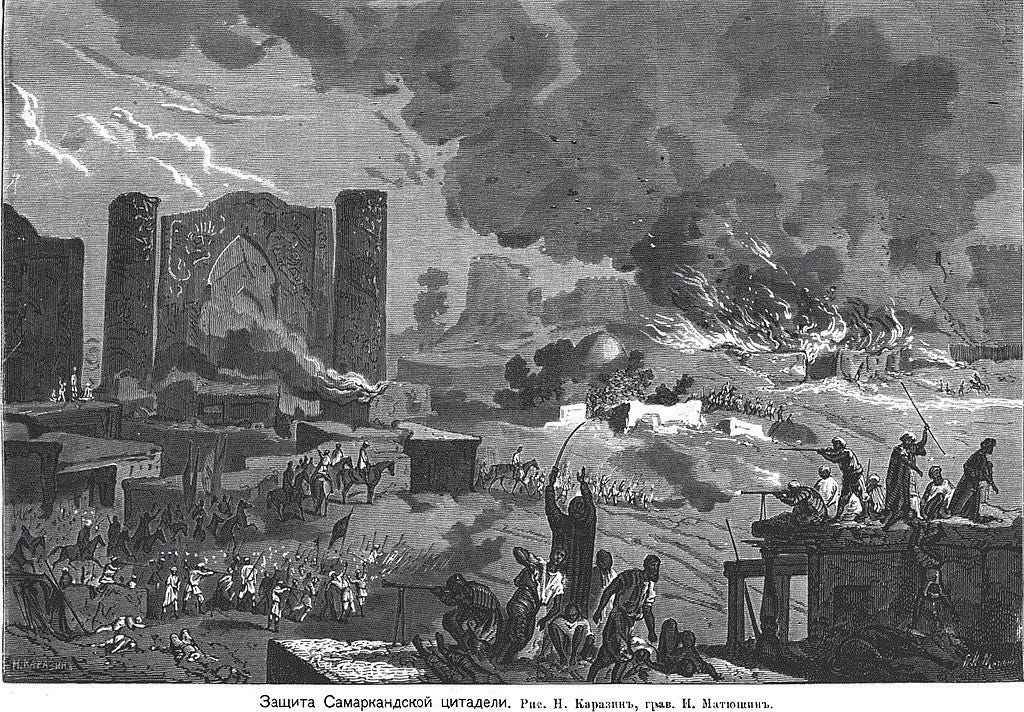

General Kaufman pursued the Bukharans down the Zerafshan Valley, leaving behind a force of 750 men to garrison Samarkand’s citadel. On 14th June 1868, Kaufman defeated the Bukharans at the Battle of the Zerabulak Heights, roughly 100 kilometers west of Samarkand, in 1868.

Meanwhile, the small Russian garrison at Samarkand came under siege by large force of local Samarkandis and irregulars from the city of Shahrisabzi to the south. Kaufman learned of the siege only after his battle, and swiftly returned back to relieve the citadel’s defenders. Bukhara now made permanent peace with Russia, and was reduced to being a Russian dependency. The Khanate of Bukhara was not liquidated by the Russian Empire, but ultimately abolished by the Bolsheviks after 1917. To further protect Samarkand, Russia defeated the ruler of Shahrisabzi, and handed the city over to Bukhara.

Russia now launched its third and ultimately successful bid to conquer Khiva. Not only was Khiva’s independence seen as a loss of prestige for Russia, especially after the two previous failed attempts to conquer it, Khiva also continued to draw Kazakh and Turkmen nomads into its orbit. These nomads continued to raid Russian lines and sedentary regions of Central Asia now under Russian control. The Turkmen especially aimed to capture people, which were later sold in Khiva’s slave markets. The Khanate of Khiva was essentially a large ulcer that was disrupting Russia’s otherwise mostly pacified southern frontier from the Caspian to the Pacific. Only the liquidation of Khiva’s sovereignty could resolve this security problem.

In 1873 Russia launched its invasion of Khiva with five separate armies. The first left from Orenburg and went south along the western shore of Aral Sea. This column entered the Khiva Oasis, but did not reach the city itself until after it was already captured. The second, left from the port of Kinderli on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea and went across the Mangishlaq Peninsula. The third, left from the other Caspian port of Chikishlyar, which is located much further south. This column ran out of supplies enroute and was forced to retreat to Krasnovodsk, another Russian port on the Caspian. Two additional columns were dispatched from Jizzakh and Kazalinsk in Turkestan. These two united enroute and continued to Khiva. The Kinderii column under the command of General Nikolai Pavlovich Lomakin and the Turkestan column under General Kaufman armies reached Khiva first, and a detachment from the Kinderii column commanded by Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was first to enter Khiva in June 1873.

As Russian forces neared the city, the Khan of Khiva accepted Russian demands but Russia nevertheless chose to conquer the city by force, largely for the sake of restoring the loss prestige it suffered during its past two attempts. Afterwards, the Russians massacred the Yomud Turkmen, who were previously aligned with Khiva.

Meanwhile in the Fergana Valley, the delicate balance of power between sedentary Uzbeks and nomadic Kyrgyz which sustained the political order in Kokand fell apart in 1873, and the city was convulsed by revolution and upheaval. A new khan seized power who attempted to maintain order and maintain Kokand’s dependency status under Russia, but he lacked the authority to enforce compliance upon the khanate’s semi-autonomous forces. Russia feared that the Islamic tinged rebellion would spread to its own territories, and soon a force of 15,000 Central Asians nominally under Kokand’s control attacked the Russian garrison at Khujand. In response, Russia invaded the Fergana Valley. Kokand was conquered and dissolved as a khanate, and later annexed it to the Russian Empire as the Fergana Oblast in 1876.

Thus ended Russia’s conquest of Central Asia’s khanates, as well as the majority of Central Asia’s settled agricultural regions. The final phase was the conquest of the nomadic Turkmen who inhabited the deserts and oases between the Amu-Darya River and the Persian and Afghan frontiers. As already seen with Russia’s massacre of the Yomud Turkmen, the conquest of the Turkmen would see the greatest levels of violence used by Russia during the conquest of Central Asia. Enemy combatants that had surrendered, as well as civilians, were regularly massacred. This violence was not arbitrary, and instead a calculated strategy meant to enforce Russian authority. This topic will be addressed in greater detail below.

Russia launched its invasion and conquest of the Turkmen from its ports on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, primarily Krasnovodsk (modern Turkmenbashi). Russia primarily used its armies stationed in the Caucasus region, and supplied them via the Volga River. Russia’s first campaign into Turkmenia was led by General Lomakin in 1879. He reached as far as the fortress of Geok Tepe (near modern Ashgabat, capital of modern Turkmenistan), but was forced to retreat. Skobelev commanded the second, more successful attempt, storming and capturing Geok Tepe in 1881. In 1884 the ancient oasis of Merv was peacefully annexed. Russia’s final push came in 1885, when it captured the Panjdeh oasis from Afghan forces, and nearly provoked a proto-world war with Great Britain in the process. For more on the Panjdeh Incident and how it nearly led to war, see my other Substack post, “The Fortress of Herat.”

In the 1890’s Russia absorbed the Pamir Mountain region (much of which today is modern Tajikistan). This was a mostly peaceful process and largely uneventful. This was done to secure a strategic buffer zone with Afghanistan and the British Raj. The annexation of the Pamir region was essentially the finishing touches to Russia’ conquest of Central Asia.

Russia held the region as a colonial possession for the remainder of the imperial era. Cotton plantations and railways were built, colonial towns and cities were constructed, and Bukhara and Khiva remained as vassal states. After the Russian Revolutions of 1917, Central Asia was reabsorbed into the Soviet Union, along with most of the rest of the former Tsarist Empire. Later under Stalin the region was divided into five Soviet Socialist Republic, which later became independent nation-states after 1991.

Morrison’s Thesis – The Will to Conquer

Along with the excellent narrative, the other great value in Morrison’s book is his thesis explaining why Russia conquered Central Asia. Morrison argues that Russia conquered simply because it could. Russia’s generals were ambitious men, the Cossacks and soldiers wanted adventure above all else, and the Russian state and society placed great value on conquest and imperialist expansion. At many points in Russia’s conquest, the commanding generals were not even authorized by Petersburg to make the advances they did. When General Chervyaev took Tashkent in 1865 he did so on his own accord, and this was repeated by other generals throughout the conquest. Whenever this occurred Petersburg accepted it as a fait accompli. During the 1873 invasion of Khiva in particular, the Russian columns were practically racing against each other to see who could storm the city first. Such was the will to conquer among the Russians. The conquest of Central Asia was simply a matter of ambitious men on the frontier who saw the opportunity for glory and took it.

According to Morrison, Russia only waited as long as did to conquer Central Asia because prior it was focused on other regions. In the late 18th century, Russia was finalizing its annexations of Ukraine and Poland, which was then followed by the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars which lasted until 1815. In the 1820’s Russia was forced to direct its energy towards the Caucasus region, against both the highlanders in the North Caucasus, and in wars against the Ottoman Empire and Persia in the South Caucasus. By the late 1830’s the Russia Empire was free to redirect its focus against Central Asia, and after the bulk of the campaigns against the khanates were complete, Russia then redirected its attention towards Manchuria and the Balkans.

Along with identifying the primary motivating cause, Morrison also dispels several alternative explanations that are commonly cited as why Russia conquered Central Asia which fail to make sense when closely examined. These include security, cotton, warm water ports and the “Great Game”. Security from the steppe nomads was already assured centuries prior to the 1840’s. Russian firepower could easily overwhelm and defeat any nomadic force. Persistent raiding still existed, but this was merely a nuisance and no longer an existential threat as it was before. The idea that Russia wanted to secure cotton resources is also easily dismissed. According to Morrison, cotton is never mentioned in the sources, and cotton production in Central Asia was only increased significantly in the 1890’s, long after Russia had conquered the region. If Russia conquered the region for cotton, scaling up production would have been one of the first things it did.

The notion that Russia has always sought warm water ports is dismissed as a purely British idea that only exists because of Britain’s own obsession with controlling seaways and strategic ports. It is essentially a case of Britain projecting its own strategic priorities as actually being Russian aims. The “Great Game” thesis is likewise rejected, as according to Morrison, Russian primary documents rarely ever mention Britain as an immediate rival or threat. It is worth nothing that with a careful reading of Hopkirk’s “The Great Game”, one can see that the “Russian threat” as a concept was largely a bureaucratic and media invention that was rolled out on occasion in order justify certain policies. Hopkirk repeatedly quotes the British media’s histrionic claims about an imminent Russian invasion of India, how divorced from reality these claims were. This is very similar to how contemporary Americans use Russia (and increasingly China as well) as a heel5 in the course of internal political fighting.

It is possible that Morrison’s thesis might appear as being too simple. Surely there must be a grander, more impersonal, and more concrete reason for why Russia conquered Central Asia. A useful historical parallel to Russia’s conquest are the campaigns of Alexander the Great. There was no pressing security threat posed by the Persian Empire towards Macedon and Greece, and if there was one it was neutralized at Issus, and decisively so at Gaugamela. There was no desire for resources, nor was there any ideological justification, similar to the role Christianity played in the Crusades or “liberal democracy” today.

One can think of Russia's conquest of Central Asia as simply a great military expedition to ends of earth, by men similar in spirit to Alexander. The Macedonian king and the Russian generals were all motivated by a desire for the grandest of adventures, to conquer and dominate, and to see lands that neither they nor any of their countrymen had ever seen before. Probably the best movie depicting this is John Huston’s “The Man who would be King” from 1975, based on the Rudyard Kipling novella.

The simplicity of this explanation risks being lost on modern readers, as modern people typically exist in a state of over intellectualization. Their minds are full of concepts and words they use in an attempt to understand the world, creating complex formulas of cause and effect, which in the end only cloud their ability to see things for being as simple as they truly are. Compare the unnecessary complexity typical to modern French philosophy, to the simplicity of Heraclitus and other Greek thinkers. Thucydides’ “Peloponnesian War” remains possibly the best book on war and international relations, not despite its simplicity, but exactly because of its straightforwardness.

It was simply conquest and adventure for its own sake. I think anyone full of life and energy can intuitively understand this explanation. Readers of Nietzsche in particular will likely not find Morrison’s thesis surprising at all. In fact, Nietzsche would likely have endorsed Morrison’s thesis himself.

Elites, Regimes, and Foreign Policy

It is also implicit in Morrison’s thesis that what constitutes a state’s “interests” and its behavior internationally is largely determined by its elite and the regime that governs it. This is another observation that is seemingly simple, yet is often obscured by overly intellectualized theories that are often found in international relations scholarship and elsewhere. Realist theories such as balance of power or geopolitics6 only really explain events in their broad strokes. Those who overly rely on these theories completely gloss over important nuisances,7 and even risk falling into deterministic lines of thinking.8

Instead of mere geography or an abstract concept like the “national interest” determining what a state’s international objectives are, it is what the elite wants and what the regime is oriented towards that determines this question. If anything, the “national interest” is whatever the elites believes it to be.

An excellent example of this is Iran. The 1979 Islamic Revolution radically changed Iran’s foreign policy, practically overnight. Prior to 1979, Iran was a close American ally, maintained friendly and cooperative relations with Israel, had peacefully resolved a border dispute with Iraq in 1975, and generally viewed revolutionary politics in the Arab world with great caution. After the 1979 revolution, Iran completely broke ties with America, made anti-Zionism a defining features of its internal ideology and foreign policy, and began promoting Islamic revolution throughout the Arab world. This sudden and total shift in Iran’s foreign policy was entirely due to the Shah being overthrown and replaced by an Islamic theocracy.

For the sake of the argument other prescient examples can be cited. The nature of the Athenian and Spartan foreign policies during the Peloponnesian War can be entirely explained as byproducts of the two states’ internal regimes. Athens promoted democracy and the overthrow of aristocracy abroad because the Athenian demos viewed fellow democracies as natural allies and wanted to prevent its own aristocrats from making allies with aristocratically ruled Greek cities, as together they could topple Athenian democracy. Sparta by contrast, protected other Greek aristocracies as it feared a democratic wave across the Greek world would result in mass popular uprisings among its helots and other subject populations. The Macedonians on the other hand, were completely uninterested in what type of regime other states had. Instead Macedon was purely oriented towards conquest and empire. This was because Philip and his son Alexander, as well as the entire Macedonian aristocracy, were only interested in dominating other states and conquering new lands. The Macedonians were generally accepting of any regime type as long as it remained loyal and obedient.

The foreign policy aims of Chinese dynasties also shifted fundamentally as a result of an uniquely fundamental change in the composition of China’s ruling elites in the 10th century. Prior to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907 – 960), Chinese states were ruled by an ancient, predominately northern based military aristocracy. With the collapse of the Tang Dynasty in 907, this aristocracy largely died out and faded away. It was replaced by the Confucian civil service elite, a class that was produced through the civil service examination system. This system had existed during the Tang Dynasty, but contributed marginally to the staffing of state positions. It was during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279) that this system became the principle avenue to gaining employment as a state official, with almost all high officials being graduates of these exams. As China’s ruling elite shifted from being principally military in nature to being scholar-bureaucrats, China became markedly less militaristic. The Song and Ming Dynasties remained on the back foot military throughout most of their lifespans. By contrast, the post-Tang dynasties that were headed by the far more militaristic steppe nomads such as the Liao, Jin, Yuan and Qing enjoyed far greater military success.

Lastly, the foreign policy of modern day America is almost entirely ideologically motivated. America as a whole derives very little from its foreign entanglements. Only the elite gain anything substantively from America’s “empire”, as it provides them with employment that is both lucrative and prestigious. Nevertheless, these policies are never understood as being vehicles for personal gain, but instead as ideological crusades for democracy, equality, human rights, etc. America’s support for Ukraine is a perfect example of a policy that is largely ideological, and ultimately only benefits those employed by the “military industrial complex”, government bureaucracies and various NGOs.

The Russian Limes9

As mentioned above, a minor flaw in the book is that Morrison does not elaborate on Russia’s fortress lines, specifically their exact purpose and their origins. This is a very important topic as these fortress lines, along with the Cossacks, were the principle means by which Russia conquered the steppes of Eurasia.

At the time of the foundation of the Kievan Rus in the 8th and 9th centuries, the Khazar Khaganate dominated the Pontic-Caspian steppes and largely maintained peace throughout the region. This came to end when Grand Prince of Kiev Syvatoslav the Great destroyed the Khazar state in 965. He had hoped to inherit the Khazar imperial sphere as its conqueror, but this did not happen. Instead the Pechenegs and other nomadic groupings, now unshackled from the Khazar hegemony, began rampaging across the western steppe lands and increasingly raided the Rus settlements along the forest-steppe zone.

From them on, the Rus existed in a state of permanent warfare against the steppe nomads, being subjected to regular raiding. It is important to understand that war and peace as clearly defined and differentiated states did not really exist for steppe nomadic peoples. Instead, the nomads essentially lived in a state of anarchy, which was defined by regularly shifting alliances, raids and counter-raids that were usually aimed at stealing other’s livestock, and clan-based blood feuds.

As a result of being directly adjacent to the steppes, Kievan Rus was made a part of this state of affairs. In fact, the Russians became at least partially nomadic themselves, and adapted to the ecological and political conditions of the steppes. This can be seen with Svyatoslav’s campaigns across the steppes against the Bulgars and Khazars, as well as the latter Cossacks. This is all the more remarkable considering that the ruling element of the ancient Russians were initially Varangians10 from Scandinavia who sailed inland and came to dominate both the rivers of northwest Eurasia as well the eastern Slavs living in the forests. In other words, the Rus were initially oriented towards a riverine and forest environment but were also able to adapt and expand into the steppe lands.11

Not only did the Rus adapt to the region’s unique ecological conditions, which demanded skilled horse riding and pastoralism as opposed to agriculture, the Rus also assimilated the political norms of the steppe. A few sources from the 9th and 10th centuries speak of the Rus being ruled by a Khagan, the imperial title of the ancient Turks that was also used by the contemporary Khazars. In all likelihood, the rulers of Kiev fashioned themselves in the Turkic imperial tradition in an attempt to solidify control over tribes that nomadized to their south on the Pontic steppes. And as mentioned above, Svyatoslav had hoped to inherit the empire of the Khazars for himself, but this failed and instead his son Vladimir the Great formed an alliance with Constantinople, converted to Christianity, and oriented the Rus towards the Roman imperial tradition. Yet the Rus nevertheless continued to assimilate the political culture and norms of steppe, simply as a result of their proximity to it.

Later, when Ivan the Terrible assumed the imperial title of Tsar, which means Caesar, he was just as much following in the tradition of the Mongol Khans12 as he was in the tradition of Roman emperors. It indicated his claim to the former Mongol Empire, and soon after Tsar Ivan IV conquered the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan on the Volga River, both remnants of the Golden Horde which itself was a remnant of the unified Mongol Empire. Just as how Kiev lay within the forests on the edge of the steppe, facing both towards the steppe and towards the northern forests and seas, Muscovy and the Russian Empire developed into a Janus faced entity facing both Europe and Asia. The Tsar was a Caesar in Europe and a Khan in Asia. And in both directions the Russian had similarly unlimited imperial ambitions as the two political cultures they modeled themselves after.

The conquest of the Volga River Khanates in the 16th century gave Russia not a controlling, but preeminent position on the Pontic-Caspian steppes. In the past when the nomads remained a grave threat, Moscow relied greatly upon fortified lines to defend itself from raids and invasion. These lines consisted of walls and other obstacles, and forts placed intermittently along its length. Prior to the 16th century, the primary line was the Belgorod Lines.

Once the Volga Khanates were taken, additional fortresses were constructed along the Volga River, which created a fortified line that penetrated deep into the steppe zone, down to the Caspian Sea. The Volga line was also extended up the Kama River, a tributary of the Volga, towards the Ural Mountains and into Bashkiria. While the Belgorod line was primarily defensive in nature, the lines created after the conquest of Volga khanates were principally offensive.

Further fortified lines were constructed along the Don River, along the Kuban and Terek Rivers which were joined to create the Caucasus Line, along the Ural River, the Irtysh, and more. The Irtysh Line was linked to the Tobol River in the west by the Ishim Line, which safeguard western Siberia from Kazakh raiding. These lines were a necessary solution for a state locked in constant warfare. It prevented raids, and even if the nomads succeeded in penetrating the line, it would be very difficult for them to exit while herding away any stolen animals.13 Additionally, the lines stopped peasants from fleeing into the steppes and draining Russia of labor.14 The Russian lines were built for all the same reasons the Chinese built their walls throughout history. Both states faced basically all the same problems vis-à-vis the steppes.

The forts themselves functioned as nodes, where patrols could be dispatched from and where trade with the nomads could be held, which was only available to them if they swore loyalty to the Tsar. A tribal leader who swore loyalty would often have to give one of his sons to the Russians as “amanat”, a hostage, who would be held in the fort. These forts linked together in a chain became a line that could control and regulate nomadic movement. The lines allowed Russia to limit the nomad’s access to grazing areas, water and salt resources depending on their political orientation. These lines were eventually linked together, for example the Don and Volga lines connected at Tsaritsyn, modern Volgograd. Intersecting line became nets that would entrap the highly mobile, hard to control nomads, fatally limiting their mobility and therefore their ability to resist the Tsarist state. The fortified lines were extended out into the steppes along river valleys, as if they were the literal tentacles of the Russian state. Eventually following the reforms of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great, these fortified lines morphed into administrative boundaries and districts.

These lines were not impenetrable though. For example, the Kalmyks south of Tsaritsyn felt themselves to be increasingly constricted territorally and administratively, and in 1771 a large contingent of them decided to migrate back to Zungaria in the Qing Dynasty. In the process of fleeing from Russian control, the Kalmyks smashed through the fortified lines along both the Volga and Urals Rivers. For more on the Kalmyks and Russia, see Michael Khodarkovsky’s “Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads, 1600–1771.”

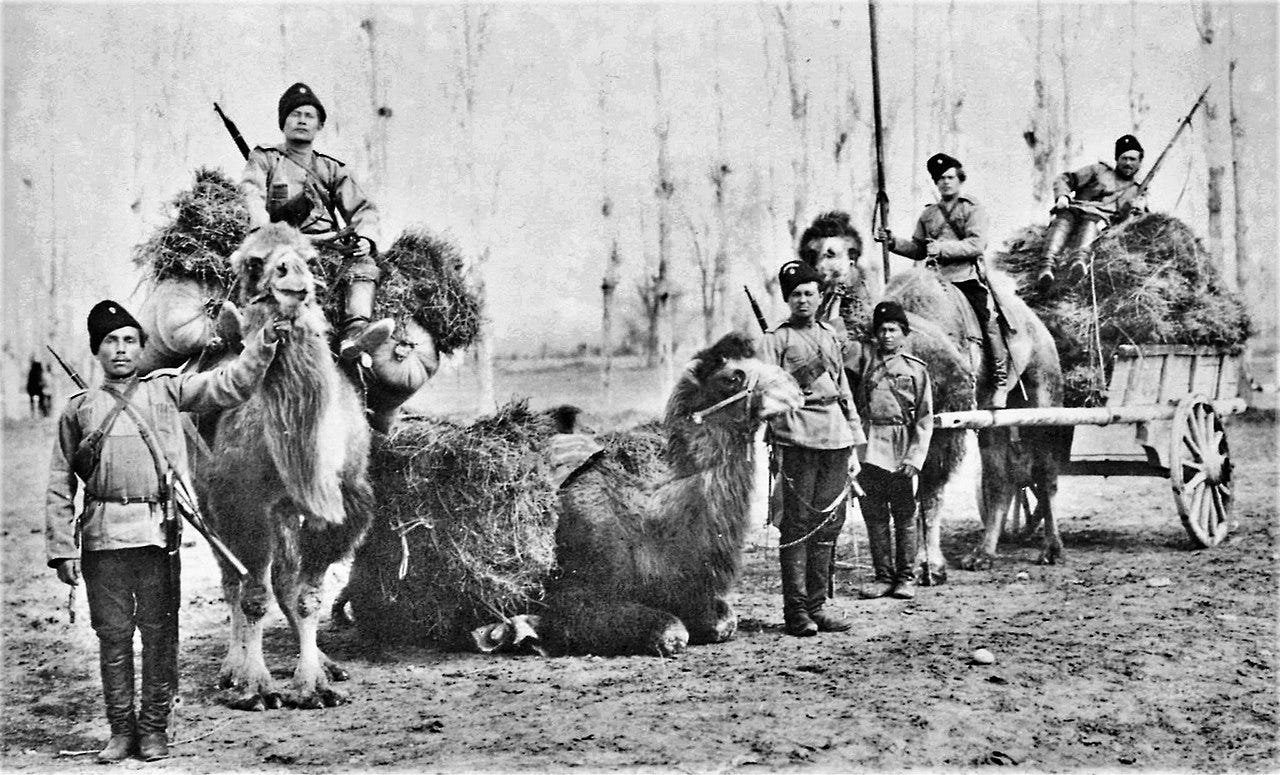

The conquest of the Volga Khanates also brought Russia into a new ecological zone, the steppe lands. Before this, the Russians, and earlier the Rus, had been primarily a people based in the forests and traveled using northwest Eurasia’s extensive river system, and portage from river to river. Siberia was later conquered by the Russians in a similar manner the Varangians had conquered the eastern Slavs. The Cossacks exploited Siberia’s great rivers and portaged between them, until they reached the frontiers of Qing China and the Pacific Ocean. But in order to expand into the steppes, the Russians were required to break into an ecological niche and adapted accordingly. The principle adapters to these new environmental conditions were the Cossacks.

The exact origins of the Cossacks is debated, but initially they likely consisted of Slavs who fled into the steppes seeking adventure and freedom. There, they took on the ways of the Turkic nomads and began to nomadize themselves. Over time, the various Cossacks hosts came under the control of Moscow and Petersburg. These Cossacks were effectively nomads themselves, engaging in similar practices of raiding and steppe warfare as their Turkic counterparts. The main difference was that the Cossacks had a large and very power Europeanized state apparatus behind them in support. The fortified lines served as the physical infrastructure to control the steppes and the steppe nomads, while the Cossacks played the decisive human role in building and manning the fortresses and outposts, patrolling the lines and frontiers, repelling raids, battling nomadic forces, and enforcing compliance and submission when it could not be secured voluntarily.

On the Eurasian steppes Russia had a decisively European face. From the 16th century onwards, European weaponry had an overwhelming effect upon nomadic cavalry forces, and especially following the Petrine reforms of the early 18th century, modern European modes of state administration were applied to the steppes in order to further constrict the mobility of the nomads. This envelopment of the steppes by the Russian state was made possible by the fortified lines which physically planted the state within the steppe zone and enclosed it within the reaches of Russian state power. These lines served a similar to how modern states today are physically delineated with border fences, checkpoints, and outposts, all of which were not common until the 20th century outside of select examples.15

While the Russian state in the east had a European face, in the west it often appeared distinctively Asiatic and nomadic. For example, Russia’s involvement in the War of the Sixth Coalition from 1813-1814, where Russia pursued Napoleon’s Grande Army into Germany after it had retreated from Russia, was only possible thanks to Russia’s vast stud farms that supplied near endless amounts of horses that Russia relied upon for its logistical tail. The Russian Army also had a very large cavalry force, which included the quasi-nomadic Cossacks and Turkic tribal levies. There are even famous anecdotes about Bashkir cavalry riding through Paris in 1814. The power of Russia has always been reliant on its ability to be simultaneously European and Asiatic when either or are required.

Contested Sovereignty on the Steppes

The main problem Russia faced with the nomads and the steppes was that it was never clear where sovereignty lay. The nomads would constantly shift their allegiances between Russia, the Khanates of Khiva, Bukhara and Khiva, the Qing Dynasty, or shun all and go it alone. This resulted in a constant state of low intensity warfare with regularized raiding as delineated states of war and peace did not meaningfully exist. This was byproduct of sovereignty being constantly contested on the steppe, there was no clearly defined state authority. To the extent nomadic states existed, they were highly fluid and ephemeral. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the nomads of the Kazakh steppes were almost entirely fragmented. Nominally there were three hordes (Zhuz), but these entities did not meaningfully exist in practical reality, thus any agreements reached with the khans or tribal leaders meant little as there were no real state structures in place which allowed Kazakhs to enforce compliance upon their followers. Essentially, a persisted state of quasi-anarchy existed along Russia’s southern frontier.

This problem was magnified by the states that existed on the far side of the steppes, to the south, and the influence they had upon the nomads. Principally, these states through their trading and religious ties to the nomads encouraged them to raid Russian lands for slaves. As far back the Scythians and the Khazars, the steppe nomads would engage in slave raiding and sell this merchandise to the sedentary civilizations to their south that required slave labor. The Scythians sold slaves to the Greek colonial cities on the Black Sea where they were exported to their mother cities, and the Khazars on the Pontic-Caspian steppes also exported slaves to the Abbasid Caliphate. Along with fur, amber and other luxury goods, slaves were the principle commodity exported from north to south in western and central Eurasia. This pattern continued well into the modern period.

Long after Russia had thrown off the “Tatar Yoke” in the 15th century and conquered the Kazan and Astrakhan Khanates in the 16th century, Russian continued to be subjected to regular slave raiding. In the first half of the 17th century alone, an estimated 150,000 - 200,000 Russians were captured by Turkic nomads and sold primarily to the Ottoman Empire to be slaves, eunuchs or as concubines in harems.16 There were also several small states along Russia’s southern frontier, whose economies were orientated towards handling the flow of Slavic slaves from north to south. The primarily one was the Crimean Khanate who reexported Slavic slaves to the Ottoman Empire, but the Shamkhalate of Tarki17 in Dagestan and the Khiva Khanate hosted significant slave markets as well.

This was not solely due to economic reasons either. As the Russians were Christian and not Muslims, it was permissible for the nominally Muslim nomads to raid the kaffir Russians for slaves. As late was the early 18th century, Turkic nomadic raids reached as far deep into Russia as Moscow. For the sake of Russia’s security, it was necessary to conquer the steppe nomads, and to liquidate the intermediary commercial middle man states that provided the markets from where slaves were sold and transported further to the Ottoman Empire, Persia and elsewhere.

A similar dynamic existed along the Kazakh steppes. The Kazakhs, as well as Turkmen further south, were politically and commercially linked to the three Central Asian khanates. The relationship with these state encouraged further raiding, as any people or goods stolen from the kaffirs could be easily sold in the khanates’ markets. What existed along the Kazakh steppes was far less of a security threat than what existed in prior centuries. The problem was no longer existential, but it did exacerbate the state of de facto anarchy that existed on the steppes.

Similar to the later Russian steppe forts which were used to control the nomads through access to trade and markets, the three khanates operated similar fortresses. Kokand for example maintained an extensive web of forts along the Syr-Darya River and across the Semireche region, as well as smaller forts in the Tianshan Mountains, from where they drew the nomads into their political and commercial orbit. For both the khanates and the later Russians, the steppes forts served as anchor points, excreting a gravitation force upon nearby tribes. To take their metaphor further, the nomadic tribes were like moons or satellites orbiting these steppe forts. That being said, tribes could drift away from the gravitational orbits of Russia, the Qing Dynasty, or any of the khanates for a myriad of reasons. When Russia began pushing south into the Kazakh steppes, it effectively replaced Kokand's steppe outposts with its own. Likewise, the Kazakhs of the Middle (northeast Kazakhstan) and Big (southeast Kazakhstan) Hordes that were aligned with the Qing Dynasty were detached and brought into the Russian fold.

Thus, the primary source of conflict between Russia and the three Central Asia khanates was that they served as competing centers of gravity in regards to the nomads. When tribes were aligned with the khanates, they had a material incentive to raid and attack Russian settlements, as anything captured could be sold to the khanates, including slaves. From the Russian perspective, the nomads were essentially proxies serving on the behalf of the khanates.

This problem was very difficult to solve because of the khanates lacked any firm degree of sovereign authority of the nomads. Any agreements made with the khanates meant to ensure an end to raiding and the selling of Russian slaves in their markets was meaningless. First, the economies, and therefore the regimes, of the khanates were highly dependent on the slave trade. Second, they could chose to simply turn a blind eye to where the tribes sources their slaves and other stolen goods. Third, they did not even really control the nomads aligned with them, and any attempt by a khanate to enforce compliance on the nomads would result in the nomads shifting their commerical relations to another khanate. And as mentioned above, nomadic tribes themselves were very difficult to reach an agreement with, as internally they were highly fragmented and generally lacked state structures and an internal sovereignty authority. As long as the nomads had alternative markets, they could disregard the interests of any particular state and look elsewhere. To control the nomads, controlling the khanates was also required.

A similar dynamic can be seen currently as well. Across the post-Soviet sphere, NATO and EU function as a rival center of gravity for the countries and elites of the former Soviet Union. The Western bloc has attempted to draw these states into its sphere of orbit, while Moscow has sought to keep these states and elites tied to itself. Without the West serving as a rival center of gravity, it would be impossible for Ukraine to resist Russia, and the Baltic state would also likely be forced to comply with Russian interests and preferences. When states such as Kyrgyzstan and Georgia, which at one point both flirted with a pro-Western direction, realized that the West’s gravitational orbit is weaker than previously thought, they realigned back to Russia. A significant reason why the much predicted Sino-Russian confrontation has not occurred in contemporary times is that Beijing has made no attempt to become a rival center of gravity in the post-Soviet sphere. Is does business with Central Asian states, but accepts that they are fundamentally within Moscow’s orbit

The entire Russian conquest of Central Asia can be understood as a continued attempt to resolve the problem of ambiguous sovereignty which existed across its southern frontier, and the poor security conditions that this produced. The initial attacks against Khiva were an attempt to neutralize one of the main centers of gravity that rivaled Russia for control of the Kazakhs in the Little Horde. The pacification of the Kazakh steppes was aimed at controlling the nomads themselves. By the end of this process it became clear that in order to sustain its hegemony over the steppes, the southern rim of the steppes needed to be controlled as well. This brought Russia into conflict with Kokand and Bukhara. But even once the three main rival centers of gravity had been subdued, the Turkmen in the Kyzyl-Kum and Kara-Kum Deserts remained. Russia understood that sedentary Central Asia would not remain stable unless the Turkmen were pacified as well. Once this was achieved by the mid 1880’s, Russia bordered cohesive, conventionally sovereign states that it could negotiate with.

Unlike the nomads and the khanates, Persia, Afghanistan and the Qing Dynasty could be relied upon to largely abide by any agreements and treaties that were made. Russia no longer faced a situation where sovereignty was contested and ambiguous, and where was there was an ever constant, low intensity war on going. Instead, Russia finally had neighbors to its south were international borders, and states of war and peace were both clearly defined. Repeatedly throughout the book, Morrison states Russia sought a “natural frontier.” What he means by this, is a frontier with states that abided by norms of international relations that were typical to Europe at the time.

Why didn’t Russia not conquer Xinjiang?

As mentioned in the introduction, “Central Asia” is really a far larger region than what the Russia conquered in the 19th century and what the Soviet Union ruled in the 20th. During both the Russian Imperial period, and in the early Soviet period as well, there were opportunities to conquer Xinjiang, but this did not occur. In fact, the Russian Empire and Soviet Union both occupied territories in Xinjiang, only to withdraw and return them to China. This occurred in 1881, when Russia returned the Ili Valley to the Qing Dynasty, and in 1949 when the Soviet Union liquidated Second East Turkestan Republic which it had been previously sponsoring. Additionally, the Soviet Union intervened in Xinjiang on several occasions in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but only in support of the Chinese provincial government based in Urumqi.

Truthfully, this question can only be explained in detail with and essay of its own, but a brief answer in summary can be provided. Russia first occupied the Ili Valley in 1871, when Xinjiang, Gansu, and other northwestern Qing provinces were being ravaged by the Dungan18 Revolt. The Tarim Basin in Xinjiang came under the control of Yakub Beg, an adventurer from Kokand, which he ruled the region as his own fiefdom. Eventually a Qing army was eventually dispatched and reconquered the region. The Russians had occupied the Ili Valley in response to the chaos unfolding in the Tarim, and justified it to Beijing as a temporary measure. With the crisis period over, Russia no longer had a reason to continue its occupation. Additionally, Russia believed itself to be already overextended, and feared that the Qing army in Xinjiang would be able to defeat and eject the Russian forces from Qing territory. Russia had no interest in war with the Qing Dynasty at the time, and feared that a defeat at the hands of China would severely damage its prestige,19 especially considering that an Anglo-French force had managed to occupy the Qing capital two decades prior. Thus, Russia returned Ili to the Qing with the Treaty of Petersburg in 1881.20

Early Soviet polices towards Xinjiang and China is a more complex issue. First, the Republic of China in the 1920’s and 1930’s was a highly fragmented country, with warlords carving out pieces for themselves and the central government lacking any real authority. Even after Chiang-Kai Shek had partially reunified China by 1928, Xinjiang remained de facto autonomous. The Soviet Union followed multiple, separate policies towards China and towards specific regions. Towards the central government, Moscow supported it and hoped to secure China as an ally against Western imperialism. The Bolsheviks hoped that if China could eject the Western powers from Chinese territory and liquidate their holdings, an economic crisis could be triggered in the West which would strengthen local communist parties.

Towards Xinjiang, the USSR hoped to keep it autonomous, ensure its provincial government was friendly to Moscow, and generally use it as a buffer state protecting Soviet Central Asia from Japanese and European imperial agents. In the 1930’s the Xinjiang province state came under the control of Sheng Shicai, who established very close ties to Moscow. Soviet political and military advisors were invited into Xinjiang, and numerous mining and lumber concessions were given to Soviet firms. Politically and economically, Xinjiang was a Soviet satellite state. This changed in the winter of 1942. During the battle of Stalingrad, Sheng thought the Soviet Union would lose the war to Germany, and proceeded to change course completely. All Soviet and Chinese Communist Party personnel were killed or interned. After pushing the Germans back from the Volga, the Soviets responded to Sheng’s betrayal by fermenting an uprising in the Ili Valley that soon declared itself the Second Turkestan Republic. Supported by weapons and advisors from the NKVD,21 the Second Turkestan Republic held off Sheng’s army. Yet, Stalin later had this organization disbanded, and likely ordered its leadership killed as well,22 in 1949 following the victory the Chinese Communist Party over the Guomingdang.

With the victory of the Soviet aligned and supported CCP, Stalin once again hoped that China would play an integral role in helping to weaken the European imperial powers and America. In order to secure China and Mao as allies, Stalin fully supported the PRC’s takeover of Xinjiang, as well as the country’s territorial integrity. Along with the Ili Valley being returned, Stalin also ended Soviet control over the Manchurian railway system and Port Arthur on the Liaoning Peninsula, two concessions the Soviets had gained in 1945. Later, following the Sino-Soviet Split, the Soviet Union planned to invade and occupy Xinjiang in the event of war with the PRC, but this of course did not occur.

Prestige

Morrison regularly states that the Russians were obsessed with their “prestige” and that with every setback or failure what Russian generals lamented more than anything else was the resulting loss of prestige they suffered. Yet despite its seeming importance, Morrison never states why prestige should matter so much. Throughout the text it appears as a very nebulous concept.

But the Russian generals were correct in placing such great importance on this matter. It must be remembered that Russian forces, and later colonists and colonial administrators, were always hugely outnumbered by the native population. If the Russians were faced by a mass native uprising, they would have struggled greatly to contain it, and even if they did it would come with great losses. Thus, Russian rule was in large part based on the perception of Russian power being all-powerful and any resistance as being futile. This partially explains why the nomads were such irritants, the mere fact of their independence served as an example and as inspiration for others. This also explains why Russian applied violence to varying degrees throughout its conquest of the region.

Application of Violence

The level of violence Russia used while conquering Central Asia was almost always correlated to the degree of native resistance it faced. The native Central Asians who suffered the greatest by Russian hands were also those who resisted the most. This included: the Khivans in 1873, the insurgents during the 1875 Kokand uprising, Turkmen, and the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz during the 1916 revolts. By contrast, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz during their initial absorption saw relatively minimal violence; Bukhara and Kokand initially saw violence that was largely in accordance with the rules of warfare at the time; and the Pamiris who did not fight Russia at all also experienced no violence at all.

Russia was much more severe to those who resisted the most, because it was necessary to make an example out them, to show others what the consequences of fighting and resisting Russia would be. This ties back to the previous section. The Russians were heavily outnumbered by natives in Central Asia, the distances were enormous and the terrain favored the nomads. Russia could only secure the region through compliance and submission by the natives, whereas mass resistance had the potential to drive the Russians out. In order to achieve this, it was necessary for Russia to show that those who submitted would be treated as friends, those who resisted would die, and anyone who managed to defeat Russian forces would die along with their families and kin.

A quote by Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev in 1882, following his massacre of the Akhal-Teke Turkmen at the Geok-Tepe fortress, clearly states the logic of Russian violence: “I hold it as a principle that in Asia the duration of peace is in direct proportion to the slaughter you inflict on the enemy. The harder you hit them, the longer they will be quiet afterwards. We killed nearly 20,000 Turcomans at Geok Tepé. The survivors will not soon forget the lesson.”

It should be noted, that prior, the Turkmen were the most formidable and independently minded of all Central Asians, but following Russia’s conquest, Turkmenistan was one of the most stable and peaceful areas of the region. Regardless of what anyone might think, Russian methods proved successful.

As a method of empire and imperialism, this is typical to other Central Eurasian empires such as the Mongols. Chingis Khan was very peaceful towards the Qocho Uyghurs and others who submitted, but was horribly brutal to the Xi Xia, Khwarazmian Empire, and especially to those who rebelled after submitting. Similar as the Russians, the Mongols were vastly outnumbered by their subjects and campaigned across vast distances and harsh terrain. For both, it was necessary to establish a reputation and to make sure their reputation preceded them. Otherwise they would not be feared, only hated, and with the hearts of their enemies and subjects only filled with hate, they would meet resistance everywhere and their empires would have come to an end soon thereafter. Russians, Mongols, and other Central Eurasian imperial peoples never sought to merely kill and destroy cities. Their preference was to take control of cities and regions mostly intact, so they could be taxed and the conquerors could enrich themselves off the labor and commerce of others. Extreme violence was instead merely used as a tool to intimidate others.

The same pattern can be seen today as well. Compare the fate of Dagestan to Chechnya, or Belarus to Ukraine. Acquiesce to Moscow is clearly rewarded, while resistance is punished with the greatest severity.

Legacy

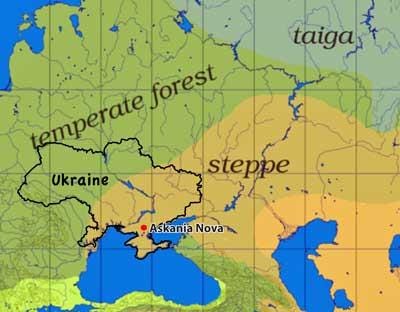

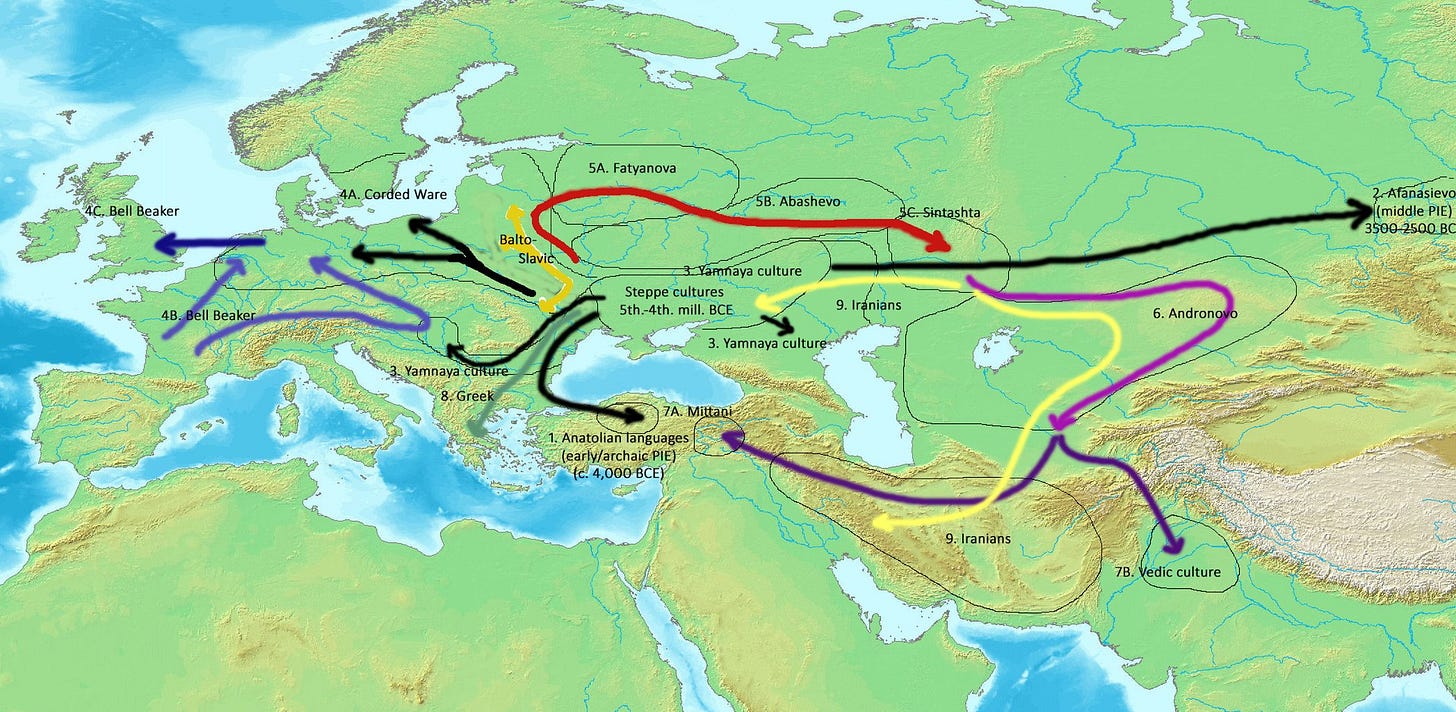

The most immediate consequence of Russia’s conquest of Central Asia is that it returned the region to being the dominion of the Indo-Europeans as opposed to Altaics. The Proto-Indo-European Aryan peoples began their expansion across Eurasia around 4000 BC. From their urheimat in the Pontic-Caspian steppes, they divided into various “cultures” and branches of the Indo-European language family. Most relevant for Central Asia, the Aryan expansions produced the Sintashta culture in the southern Ural Mountains, the Andronovo culture in eastern Kazakhstan, the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex culture along the Amu-Darya River, and the Afanasievo culture in southern Siberia.

Beginning in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, the Indo-Europeans Aryan peoples on the steppes were replaced by Altaic speakers, a process which began with the westward migration of the Huns, and continued with later migrations of the Oghuz, Avars, Turks and Mongols.23 With the Russian conquest came the partial linguistic Russification of local peoples and the colonization of the region by Slavic settlers. That being said, most Central Asians continue to speak Turkic languages. The Russian Revolutions, and especially the Soviet nationalities policy and korenizatsiya24 served to reduce Slavic dominance over the region, and the breakup of the Soviet Union only reduced it further.

Economically, the conquest has proved huge beneficial for Russia. In the short term, ruling Central Asia was net drain on the imperial state’s budget. Nevertheless, it did secure important resources for Russia, namely cotton which was necessary for the Russian Empire’s burgeoning textile industry. Today, Central Asia serves the Russian Federation as a large pool of cheap labor that partially compensates for Russia’s own low birth rate and high emigration. Similar to how the Anglicization of India, Africa and elsewhere created in modern times a large labor pool of partially acculturated, low cost labor for the Anglosphere, the Russian conquest of Central Asia had a similar consequence. An underappreciated fact is that Russia's war in Ukraine is likely only possible thanks to Central Asian guest workers, whose labor fills the gaps left by Russia's increasingly large military-industrial complex and mobilization.

Conversely, the Russia conquest had horrific environmental consequences. The drying up of the Aral Sea is well known, but additionally the nuclear testing in Kazakhstan caused great damage, both environmental and birth defects. The massive expansion of irrigation, the cause of the Aral Sea’s disappearance, also led to destruction of much of the region's natural environment. Under the Soviet Union, every inch of the oases which could be irrigated and made into farm land was made so. Babur, the founder of the Mughal Dynasty in India, tells in his memoir of Fergana as being a paradise of forests and deer, whereas today the Fergana Valley has been terraformed into an enormous cotton plantation.

More generally, Russia and Soviet Union brought the inhabitant of Central Asia into the modern age. The Soviet Union in particular created industries, hospitals, schools, and other facets of the modern world. Additionally, the Soviet Union left behind a series of modern nation-states in Central Asia, bequeathing Westphalian statehood upon the peoples of the region. In this sense the Soviet Union is similar to the Roman Empire, in whose wake also left behind several successor states that were partially formed in its own image.

Central Asia’s strange modern borders should also be explained. It is often thought these borders are a result of Stalin’s scheming, and his desire to rule the region through a “divide and conquer” strategy. This is not true. The borders of the Central Asian republics were created based upon demographic and economic considerations. In the Fergana Valley in particular, an attempt was made to provide the mountainous, less urban republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan with access to urban centers which would have aided their ability to economically develop. This is why Osh and Jalalabad are within Kyrgystan, and Khujand is a part of Tajikistan. Additionally, it is worth noting that Stalin and the rest of the Soviet state never planned for the Soviet Union to dissolve. When Stalin wanted to assert his control over Central Asians, and others, he simply had people arrested, executed and imprisoned. More broadly, Stalin regularly chose to relocated peoples to different territories as opposed to gerrymandering.

Post Script

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Russians and British during their imperial rivalry viewed each other with respect and admiration. Naturally, much of this sense of mutual respect was lost during the Cold War due to the conflict’s intensely ideological and existential nature. Today hostility has continued and actually worsened, but only on the Western side. I can say with experience, Russian institutions and those who staff them do not despise the West as Westerners despise Russia. Western academia in particularly is far more hostile to the modern Russian Federation than it was to the Soviet Union, as bizarre as that might seem. All of this can be explained by the fact that the intense revolutionary and ideological spirit that inspired the Bolsheviks now exists in the West. If the Soviet elite were Marxists, then the Western elite are Fabians.25 This is all very unfortunate. In many ways, modern Russia is one of the few countries today that seeks to preserve what remains of European high culture. Seeking to exterminate Russia in the name of “liberal democracy” is an insane ideological crusade, no different than the Bolsheviks’ desire to exterminate the European way of life a century ago.

International conflict and rivalry is normal and often unavoidable. If Russia and Western countries must be at odds, then so be it. But Westerners believe in ridiculous things, only unanchored moralism and extreme decadence could produce our contemporary ideological climate. The Great Game Players viewed each other merely as fraternal rivals. No other people in the past several centuries have demonstrated a will to conquer at such a universal scale as the Russians and the Anglo-Saxons. We should understand that we are more similar than we are different.

Along with the Tarim Basin and Zungaria, Przhevalsky also wanted Russia to annex all of Mongolia, Tibet, Manchuria, and Gansu

Urban Iranic speakers were also called Tajiks often. The complete Turkification of what is now Uzbekistan was a consequence of Soviet Union’s nationalities policy

Commonly known as Bukharan Jews. Often employed in skilled craftsmanship such as carpet weaving and dyes

Russian for “Seven Rivers”, in reference to the rivers which feed into Lake Balkhash

Heel (professional wrestling): “a wrestler who performs the role of the unsympathetic antagonist or adversary in a staged wrestling match”, from Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Of course, international politics are not staged, but this dynamic plays out similarly nevertheless. Examples of this include “Russiagate”, which proved to be fake and was instead an attempt to smear Trump, and Trump’s repeated claims that China controls Biden

The role of geography in determining a state's internal and foreign policies

It is worth noting that John Mearsheimer’s “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics”, one of the most important realist texts, focuses almost exclusively on intra-European affairs, where all the actors shared the same norms and values. More broadly, one of the primary flaws in realism is that it assumes all actors share similar norms and an equal ‘will to power’, which is simply not true.

Based on a simplistic understanding of geopolitics, the continued Sino-American cooperation and close trade ties make almost no sense. Understanding the world purely through the lens of a security competition completely fails to explain why America has done so much to aid China’s rise since the year 1990’s onwards, especially in regards to American trade policy

Modern term for the Roman Empire’s frontier defensives, which consisted of a line of forts, among other things

Vikings are often called Varangians in the east, as this is what Byzantium called them

Another example of a northern forest people who were similarly able to adapt and expand into the steppes were the Jurchens, a Tungusic people from northern Manchuria who established the Jin Dynasty in the 12th century

Themselves following in the Turkic imperial tradition

The older Chinese “Great Walls” were often only a meter or two tall. Their primary purpose was to simply make it too difficult for nomads to herd away animals or cart of amounts of goods

While serfdom existed prior, as an institution it was expanded and the peasants were further disenfranchised following the “Time of Troubles” in the early 17th century, where Russia lost up to the third of its population. This was because of the increased shortage of labor and the need to prevent peasants from leaving and going elsewhere. Additionally, serfdom was likely more than mere slavery, at least initially. The word “serfdom” in Russian is either крепостное право (“fortress law”) or крепостная зависимость (fortress dependency”). These two terms imply serfdom was based on peasants being tied to a fortress, both for the purpose of supplying the fort and as a place to seek protection during a nomad raid. I should note, I am neither an expert in Russian language etymology or serfdom. Above is simply a theory of mine, which I believe to be mostly correct. The necessity of supply these fortified lines and ensuring they had apple supply of food, which was done by tying the serfs to the fortresses, is a major factor in why Russia developed such an autocratic political culture.

For much of Eurasian history, the borders of states were demarcated by signs if at all, and state power was felt in the form of tax collection at towns and cities, or at specific geographic points like mountain passes or river crossings. Situations as existed with China’s Great Walls or the Roman walls in Britain and its limes along the Rhine and Danube were the exception. And as indicated above, these structures were built for similar purposes as the Russian lines. In fact, the Russian lines were basically the Great Wall or Hadrian’s Wall recreated in miniature but far more extensively

Mikhail Khodarkovsky, “Russia’s Steppe Frontier”, page 21.

Located at modern day Makhachkala

Dungans are Chinese Muslims, also known as “Hui” in Chinese

It should be noted that Russia found itself in a similar position on the eve of the 1904-5 Russo-Japanese War. Russia had overextended itself and in the process provoked a hostile response from Japan. But unlike with the Ili crisis, the Russian leadership lacked the good senses to withdraw before the disaster could manifest itself

See “The Russian General Staff in Asia” by Alex Marshall for more on this incident

The Stalin era secret police. Later became the KGB

The leaders of the Second Turkestan Republic conveniently all died in a plane crash in Soviet territory

Some speculate that there was a degree of Indo-European and Aryan influence upon the Altaics. Many aspects of ancient Turkic political culture and lifeways closely resemble the Indo-Europeans, and thus in all likelihood there is some degree of influence, but the extent of which is debated. It is known that Indo-European Aryans expanded as far east as Gansu province and Ordos in China, and into the western Mongolian plateau and the Altai Mountains. The ancient steppe empire of the Xiongnu was likely made of up peoples with both Caucasian and Asiatic features

“Коренизация” – “taking root”, or “indigenization”. This policy gave political and cultural power and autonomy to local peoples within the USSR. Throughout the early Soviet period (before 1945), the Soviet state shifted back and forth between promoting Russification and promoting local cultural autonomy.

Fabians wanted to achieve socialism gradually through reform as opposed to revolution

"In many ways, modern Russia is one of the few countries today that seeks to preserve what remains of European high culture." One more reason for the woke western elite to hate russians. Plus as white people they are perfect to be cast as villains.

I could study the maps and images all day long. You are correct that most of us who know anything about this period know it from Hopkirk's gems and dusty British travel logs. (I still have a box of them somewhere in the barn.) So great to learn something of the other side. Thanks for this treat.