The Caucasian - Mikhail Lermontov, 1841

Translation of an essay on how Russians "went native" in the Caucasus

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of the essay “Кавказец” (The Caucasian) by Mikhail Lermontov. Lermontov was a Russian army officer and writer who served in the Caucasus in the 19th century, and is best known for his novel “Hero of Our Time,” which tells the story of the nihilistic officer Pechorin and his adventures in the Caucasus. This essay should be viewed as a complementary text to be read alongside “Hero of Our Time.” For a longer biography of Lermontov and explanation of Russia’s 19th century conquest of the Caucasus, see my introduction here. The source for this translation can be found here, under the “проза” section. I learned of this essay while recently re-reading Alexander Etkind’s excellent book “Internal Colonization”, which I would highly recommend.

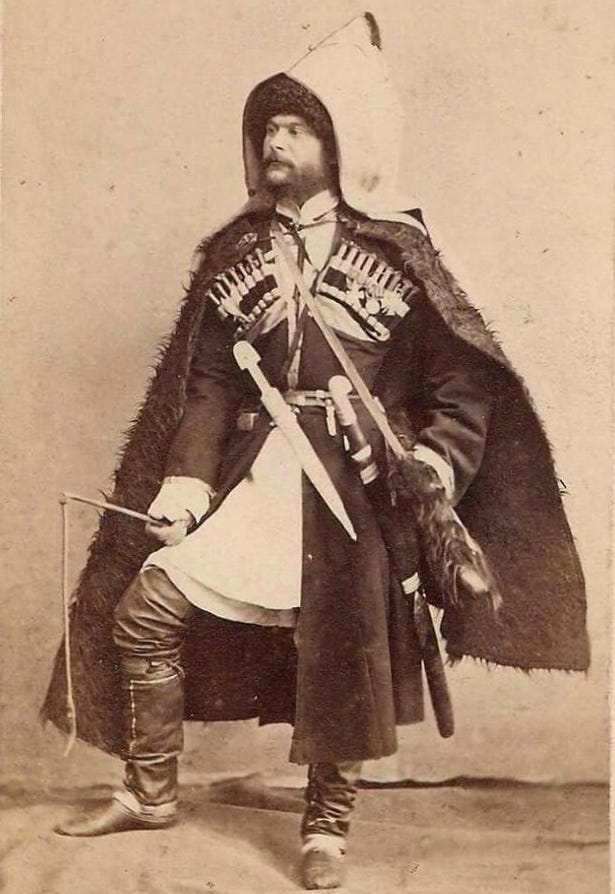

Lermontov’s essay was written in 1841, but was only found and published in 1929 by Nikolai Osipovich Lerner. The essay outlines the profile and life of a typical Russian who served in the Caucasus in the 19th century, and specifically how he “went native.” According to Lermontov, as a Russian spent longer and longer in the Caucasus he adopted more and more of native’s customs, including dress, vocabulary and even morals. Nor would he "de-assimilate” and become fully Russian again after he left the Caucasus. Instead he kept on wearing his kinzhal sword and his burka overcoat.

The place that the Caucasus holds in Russia’s cultural horizon cannot be underrated. For Russia in the 19th century the Caucasus represented an exotic frontier similar to what the Wild West was for America, and likewise served as a setting for many novels, poems, films and more. The landscapes and peoples of the Caucasus are as charming as they are wild, and in many ways the mountains seduced the Russians into becoming Caucasians more so than the Caucasians were assimilated by the Russians who conquered them. The 2003 film “Война” (War) set during the Chechen Wars highlights this quite nicely, where a Chechen warlord, after being defeated and captured in his own mountain village, congratulates the Russian solder Ivan by telling him that he has become a highlander. This paralleled events that were ongoing in Russia and the Caucasus at the time. Putin first rose to power by stopping the Chechen invasion of Dagestan in 1999, and later cemented his rule by forcefully bringing Chechnya back under Moscow’s control. It is said that only a Caucasian can conquer the Caucasus.

Aside from its historical and anthropological context, this essay really should be read alongside Lermontov’s novel “Hero of Our Time.” Maksim Maksimovich, a character from the novel, is immediately recognized as being the same type of person that Lermontov is describing here (see excerpt below). A noteworthy aside, Tsar Nikolai I, while despising Lermontov’s novel, loved the character of Maksim Maksimovich.

The Caucasian

First, what exactly is a Caucasian and what kinds of Caucasians are there? A Caucasian is in essence only half-Russian and half-Asian; an inclination to eastern customs has taken hold of him, but he is ashamed of it when viewed at by outsiders, those being visitors from Russia. He is mostly 30 to 45 years old; his face is tanned and a little pockmarked; if he is not a staff captain, then he is surely a major. Real Caucasians can be found on the line;1 they have a different tone over the mountain in Georgia; Caucasians in the civil service exist; for the most part they are awkward imitations, but if you encounter a real one, they are usually among regimental medics.

A real Caucasian man is brilliant, worthy of all respects and honors. Up to the age of 18 he was brought up in the cadet corps and graduated from it as an excellent officer; while in class he slowly and quietly read “Prisoner of the Caucasus”2 which ignited his passion for the Caucasus. He along with 10 comrades were sent there on state funds with great hopes and little baggage. While he was still in Petersburg he sewed himself an akhaluk,3 got himself a furry hat4 and a Circassian5 whip for the coach driver. Arriving to Stavropol, he paid greatly for a worthless kinzhal,6 and for the first few days he wore it day and night until eventually growing tired of it. In the end he joined his regiment, which was located in its wintering quarters in some kind of stanitsa,7 there he fell in love, as it happens, to a Cossack girl, before he heading off on an expedition; all wonderful things! Such poetry! Here they go on an expedition, with our young man throwing himself anywhere that a single bullet could fly.8 He imagines we will catch two dozen mountaineers with his bare hands, he dreams of terrible battles, rivers of blood and a general’s epaulets. In he dreams he performs knightly deeds – but it’s a dream, nonsense, the enemy is nowhere to be seen, fights are rare, and to his greatness sadness, the mountaineers cannot stand up to bayonet charges and nor do they surrender, they take their bodies and flee. Meanwhile, the summer heat is grueling, and the autumns are full of mud and cold. It’s boring! Five, six years flash by: each one is no different from the last. He gains experience, becomes able to brave the cold and learns to laugh at the new guys, who stick their heads up without any need.

Although crosses hang from his chest, no rank is forthcoming. He becomes gloomy and silent; he sits by himself and smokes from a small pipe; at the sloboda9 he also reads Marlinsky10 and talks about how good it is; he no longer earns to go on expeditions: his old wound hurts! The Cossack girls no longer charm him, he once dreamed about a captured Circassian, but now he no longer remembers her as anything more than an impossible dream. However he has a new passion, and now he has been made into a real Caucasian.

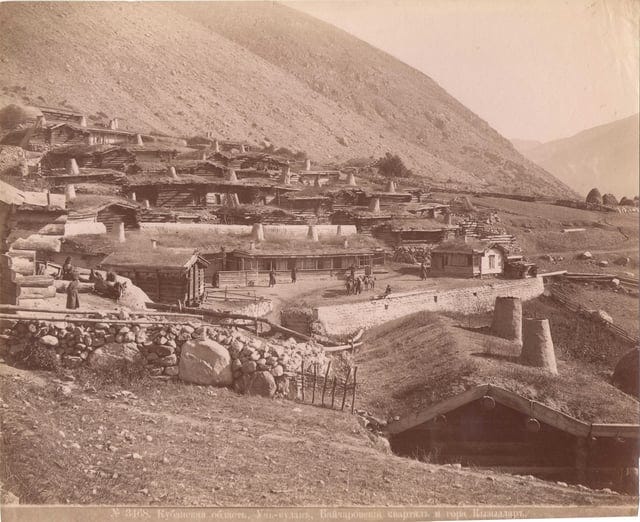

This passion was born in such a way: as of late he has become friends with a peaceful Circassian, and started travelling to his aul.11 As a stranger to the refinements of secular and urban living, he falls in love with the simple and wild life; not knowing the history of Russian and European politics, he becomes totally enamored with the poetic legends of a warrior people. He completely understands the morals and customs of the mountaineers, having learned the names of their heroes and remembered the pedigrees of their leading families. He knows which prince is reliable and which is rogue, who is friendly with whom and who has a blood pact with whom. He gently scribbles in Tatar; he has started wearing a sword, a real one, a kinzhal - an old bazalay,12 a pistol with trans-Kuban13 finishing, an excellent Crimean rifle which he himself can clean, a horse – a pure shallokh14 and dresses entirely in a Circassian custom, which is worn only for important occasions and was sewn for him by some sort of wild princess. His passion for everything Circassian reaches to such an incredible extent. He is prepared to spend all day talking about his friend’s dirty horse, and his own worthless horse and rusty rifle, and very much loves to force others to hear about the secrets of Asian customs. There have been a few different surprising incidents with him, so let’s hear them. When a new guy buys a gun or a horse from his uzden15 friend he only smiles slyly. This is how he speaks about the mountaineers: “they are a good people, only they are Asians! Chechens, truly, are rubbish, however the Karbadians are great guys; well, between them they have the Shapsugs16 who are a decent people, it is only that the Karbadians are not all equal, nor can they dress like that, nor ride past them… nevertheless, they live in a clean way, very clean!”

One must have the mentality of a Caucasian to find anything clean about a Circassian saklya.17

The experience from long campaigns did not teach him the inventiveness of a typical army officer; he shows off his carelessness and habit of enduring the inconveniences of military life, he carries only his teapot, and rarely is shchi18 boiling over his bivouac fire. Regardless if the weather is hot or cold he wears an akhaluk under his jacket and a sheep hat on his head; he has a strong prejudice against overcoats in favour of burkas;19 the burka is his toga, he drapes himself in it; rain pouring over his shoulder, wind blowing into it – it’s nothing! The burka, glorified by Pushkin, Marlinsky and the portrait of Ermolov,20 never comes off from his shoulder, he sleeps in it and covers his horse with it; he tries all sorts of tricks and swindles in order to get a real Andi21 burka, especially a white one with black border at the bottom, only to then begin looking at others with contempt. In his own words, his horse can gallop marvelously – far into the distance! That is why he is not with you when all you want to do is to gallop only 15 verstas.22 Although the service is very hard for him, he will always praise the Caucasian life; he tells everyone that service in the Caucasus nothing but pleasant.

But the years go on, the Caucasian is already 40 years old, he would like to own a house, and if he is not wounded, he proceeds with this aim in such a way: during a shootout he hides his head behind a rock, and his feet up for a pension; this expression is a sanctified custom in the Caucasus. A benevolent bullet will hit him in the leg, and he will be happy. He retires with a pension, buys a cart, harnesses it to a pair of riding horses and little by little heads home; however, he always stops at post stations in order to chat up anyone passing by. Upon encountering him it becomes immediately obvious that he is a real Caucasian, as even as far as Voronezh he still has not taken off his kinzhal or sabre, as they do not brother him. The stanitsa station master listens to him with respect, and only here is the retired hero allowed to boast about himself, and even invent a story; while at the Caucasus he was modest, and after all, who in Russia can prove that his horse cannot gallop 200 verstas in a single sprint and that no gun can hit a target at 400 sazhens?23 But alas, more often than not a Caucasian will lay his bones down in Muslim lands. Caucasians rarely marry, but if fate has burdened him with a spouse, he will try to be transferred to a garrison and will end his days in some kind of fortress where his wife will protect him from the fatal habits that Russians are prone to.

Now, two additional notes on other types of Caucasians, not the real ones. A Georgian Caucasian is different from a real one in that he very much loves Kakhetian24 and wide silk pants.25 State employees in the Caucasus rarely dress in Asian clothing; he is a Caucasian more in the soul than in the body: busy with archaeological discoveries, and discusses the possibility of trade with the mountaineers and about the means to conquer and educate them. He only served there for a few years. He usually returns to Russia with a rank and a red nose.

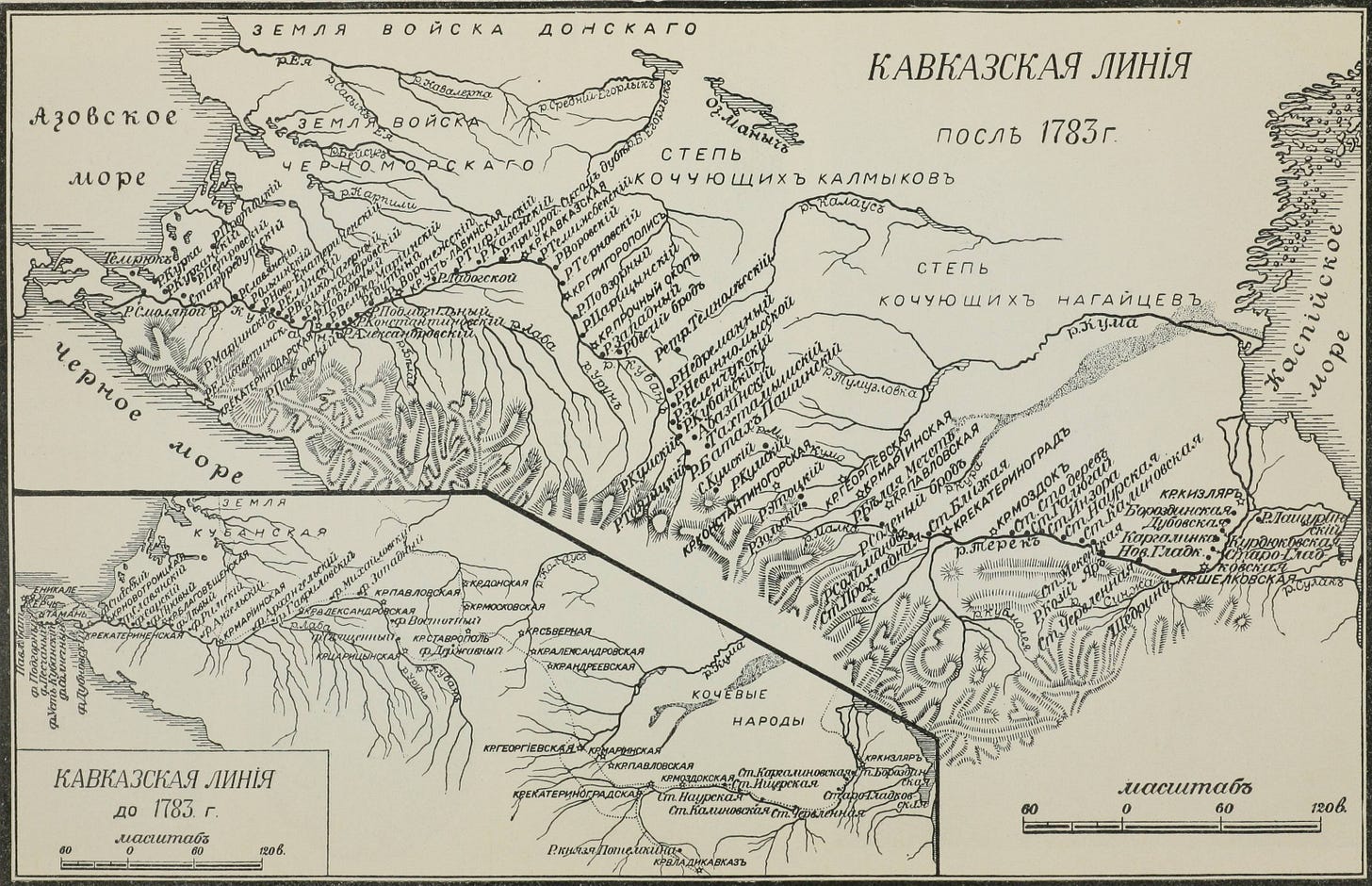

Modern photos from Twitter account Чики

The Caucasian Line, a chain of forts and outposts along the face of the North Caucasus guarding against raids by the highlanders

Like the poem by Pushkin which was published in 1822. The Tolstoy novella was only published in 1872

A kraftan of Caucasian origins, made from silk or cloth

A papakha

Circassians were the people living around the Kuban river and the western end of the Caucasus

A long Caucasian dagger

A type of Cossack settlement

This was an awkward to translate sentence, the original says: “Вот пошли в экспедицию; наш юноша кидался всюду, где только провизжала одна пуля.”

A type of Cossack settlement

Alexander Alexandrovich Bestuzhev, a Decemberist writer who wrote under the name Marlinsky

A Caucasian village

Bazalay was a Kumyk (a small ethnic group from Dagestan) clan that specialized in crafting high quality kinzhals

“Trans” meaning “beyond the Kuban River”

This is the name of a particular Circassian whose horses were greatly favoured in the Caucasus

A term for a free person in the Caucasus

A powerful Circassian tribe, from modern day Adygea and Krasnodar Krai

A Circassian home

A Russian soup

A large jacket worn in the Caucasus that can also be slept in. Not to be confused with the Islamic face covering dress

Russian general, fought in the wars against Napoleon and started the main effort to conquer the high Caucasus

A small ethnic group in Dagestan. The Andi speak a language similar to the Avars, and in along the Chechen-Dagestan border in the mountains, near Botlikh and Lake Kezenoyam

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 km / 3,500 ft

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.1336 m/ 7 ft

A region of eastern Georgia

“шаровары”

This was fascinating! Thank you for writing / translating

This is splendid! After I finish reading 'The Brothers Karamazov' I plan to read 'A Hero of Our Time'. Grateful to thee for this essay.