The Collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate and the Uyghur Migration across the Silk Road

The Rise and Fall of the Toquzoguz in the Context of Eurasian History

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

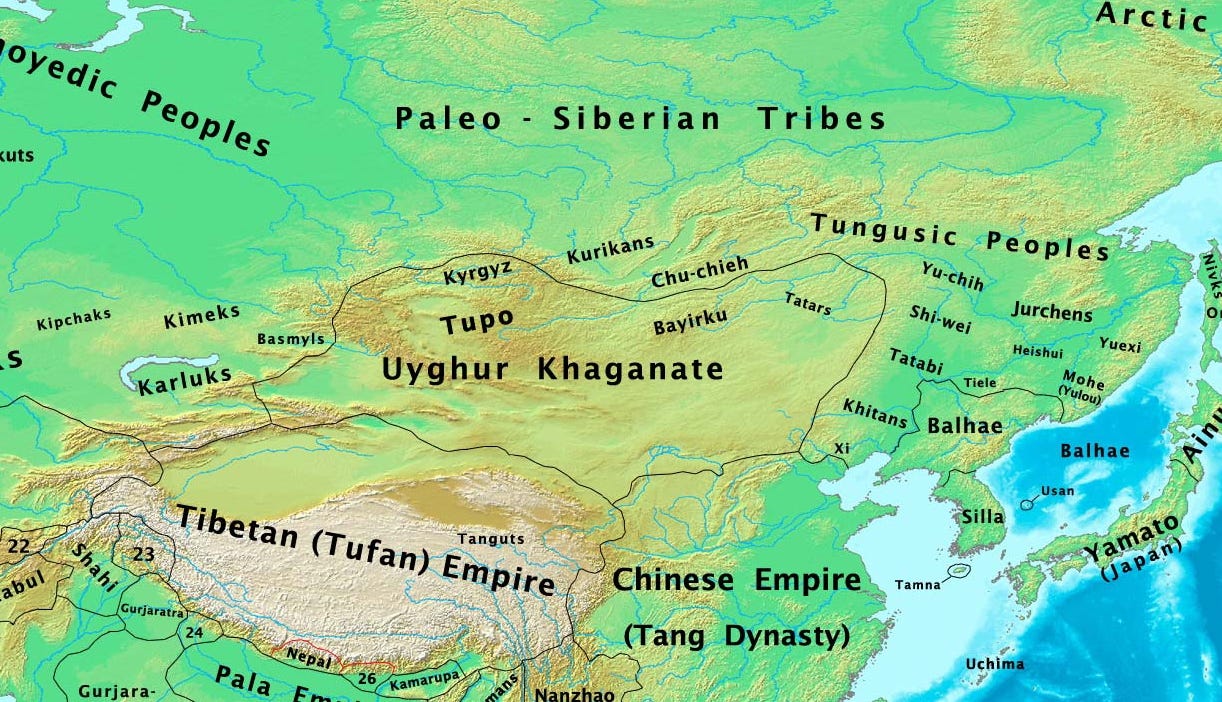

In 840, the Uyghur Khaganate at the height of its power was annihilated by the Yenisei Kyrgyz. The semi-nomadic Kyrgyz from southern Siberia struck seemingly out of the blue. They sacked the Uyghur capital of Ordubaliq, and in an instant shattered the entire Khaganate as a unified political entity. For a century the Uyghurs, a Turkic nomadic people, had ruled a great empire on the steppes of the Mongolian Plateau1 north of China, which stretched from Manchuria in the east to the Tarbagatai Mountains2 in the west. The Uyghurs initially established their empire in 744 following their successful revolt against the Second Turkic Khaganate, and soon became the most powerful nomadic empire to rule the eastern Eurasian steppes prior to the Mongols. The downfall of the Uyghur Khaganate ended the epoch of Turkic hegemony on the steppes and triggered the greatest geopolitical revolution on the Eurasian steppes since the rise of the Turks three centuries prior.

The destruction of the Uyghur Empire triggered the mass migration of Uyghurs to the south fleeing from the Kyrgyz. In the course of their exodus, the Uyghurs fled across the Gobi Desert to varying destinations. Whereas the Uyghurs had been unified tribal grouping on the steppes, as refugees the fate of each grouping was unique to itself. Some of the Uyghurs would succeed in carving out new states for themselves, going on to create cultural achievements that arguably out shined anything that was accomplished during the Khaganate period, while others perished in the arid wastelands of the Gobi Desert.

The Uyghur migrations forever altered the cultural landscape of Inner Asia. As a result of their migrations to new lands, Turkic languages became dominant across the Silk Road, while the Uyghurs themselves were transformed from being a great military power to an artistic one. As will be seen, the cultural legacy of the Uyghurs is enormous despite its obscurity. Arguably the Uyghurs had a far greater impact on world history in the cultural sphere than in the military and imperial state building sphere.

The history of the Uyghur Khaganate’s collapse and the subsequent Uyghur migrations serve as an interesting case study of how steppe empires collapse and the ensuing reshuffling of territory that occurs as a result of nomadic migrations. Additionally, the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate intersects with one of the most interesting periods of Chinese history. The fate of the Uyghurs who fled to the Great Wall frontier is particularly illustrative in how the once highly cosmopolitan Tang Dynasty had evolved into a guarded, xenophobic state. In general, the history of Tang China and the Uyghurs make for a great case study of nomadic-Chinese relations, and the dynamics involved.

Tang China and the Rise of the Uyghurs

To understand anything about the Uyghur Khaganate, one must begin with the An Lushan Rebellion that convulsed the Tang Dynasty at its imperial apogee. Imperial China had been initially unified by the state of Qin in 221BC. Shortly after the death of the first emperor Qin Shi Huang, the Qin Dynasty collapsed and was seamlessly replaced by the Han Dynasty which ruled for nearly 400 years, before collapsing itself in the 3rd century AD. The collapse of the Han Dynasty was followed by centuries of fragmentation as China was ruled by several small, competing dynasties. Much of northern China was conquered by proto-Turkic steppe nomads who created hybridized dynasties that had both nomadic and Chinese characteristics. This period of fragmentation came to an end in the later 6th century, as the Sui Dynasty successfully reunified China. Yet, the Sui Dynasty was destined to play a similar role as the Qin Dynasty. The Sui became bogged down in a failed invasion of Korea and local rebellions sprung up against imperial authority. Ultimately, the Sui collapsed and its imperial house of Yang was replaced by the Li family, whose power base was in the north of modern day Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia. The Lis were not wholly Chinese themselves, but decedents of both Han and proto-Turkic nomads, the biological legacy of the hybrid nomadic-sedentary dynasties which had ruled northern China during the Han-Sui interregnum.3

The Janus-faced nature of the Li family provided them with connections to both the world of China and the steppes. As the Sui Dynasty disintegrated, the head of Li family, Li Yuan, formed an alliance with the Turkic Khaganate on the steppes and then marched south. In the course of a brief campaign, Li Yuan defeated what remained of Sui forces in the Fan and Yellow River valleys before entering Chang’an, China’s imperial capital (modern day Xi’an). There, Li Yuan declared himself Emperor Gaozu of the Tang Dynasty, and quickly moved to reunify the fragmented Sui Empire under his new dynasty. With China unified, the Tang rapidly conquered first the Eastern Turkic Khaganate centered on the Mongolian Plateau, and then swiftly conquered the Western Khaganate centered in the Semirechye4 region of modern day southeastern Kazakhstan and northern Kyrgyzstan. By 650, Emperor Gaozu was both the “Son of Heaven” and the “Heavenly Khagan”, ruling both China and the steppes.5

The Tang Dynasty would become a highly cosmopolitan empire, whose power and influence reached as far as Samarkand and the Pamir Mountains. It was the preeminent state during the early medieval era of the 7th and 8th centuries, with the eastern Eurasian world orbiting around the Tang court in the imperial capital of Chang’an, a city whose population reached 2 million at its peak, the largest urban center of its era. The majesty and hegemony of the Tang resulted in the creation of a widespread commercial network that spanned the entirety of Eurasia, commonly known today as the ‘Silk Road.’ In the year 744, not only was the Tang Dynasty at the height of its power, it also represented China’s civilizational apex, imperial China’s equivalent to Rome in the era of the Emperor Trajan.

Yet the Tang’s power belied a growing malaise. By the 750’s life at the Tang court under Emperor Xuanzong had become decadent and consumed with vapid pursuits. Foreign entertainment such as Kuchean dancers pervaded court at the expense of actual governance. Under Xuanzong, the Tang drifted away from an autocratic mode of governance to an oligarchic one, while the emperor himself was solely interested in the arts and his concubines. By 755 actual management of his empire was in the hands of bureaucrats and court fractions.6 Simultaneously, centrifugal forces on the empire’s periphery worsened, with local elites gaining power at the center’s expense. And lastly, of all the Chinese dynasties the Tang was uniquely cosmopolitan, with many Sogdians from Central Asia serving as imperial officials, while Turks and other nomadic peoples served in the army. Many of these peoples were not primarily loyal to the Tang Dynasty, but instead loyal to each other or their kin who were outside of the Tang realm. All of these trends culminated in the rebellion of An Lushan at the end of 755.

Born to a Sogdian father and Turk mother and initially named as Rokhshan, An Lushan became the Jiedushi (military governor) of the Youzhou region, the Tang’s northeastern frontier facing Manchuria.7 In the years preceding his rebellion he had enjoyed imperial patronage, thanks to his close relationship with the Lady Yang Guifei, Emperor Xuanzong’s favored concubine. The exact nature of the relationship is uncertain, but is known is that An enjoyed the protection and patronage of the Yang family, who had become a powerful clique within the imperial court due to Guifei’s relationship with the emperor.8 By 755 the Yang family had gained immense wealth and power, and under their influence the Tang court was blind to the looming catastrophe. The disaster was brought about through a combination of imperial hubris, fecklessness, and xenophilia, and the ensuing cataclysm “shook all under heaven.”9

In the final days of 755 An Lushan launched his rebellion and marched south towards Chang’an across the Chinese Central Plain, and in early 765 An declared himself the emperor of the Yan Dynasty. Yan forces swiftly captured the imperial capitals of Luoyang and Chang’an, sending the Tang court fleeing in exile to Sichuan and Ningxia. The rebellion would ultimately drag on for 8 years, killing and displacing up to a third of China’s population. In truth, it was less a civil war as the term ‘rebellion’ would imply, but instead an invasion of Turkic and Manchurian steppe tribes led by a Sinicized elite under the banner of a pseudo dynasty.

The conflagration that was instigated by An Lushan left the Tang severely crippled. The dynasty never fully recovered from the war. At the rebellion’s outbreak, Tang armies were scattered across the empire’s distant frontiers in Inner Asia. They were immediately withdrawn to respond to An Lushan, which left the Tang’s holding west of the Yellow River defenseless. Tibet, which was the Tang’s main rival in the region, quickly filled the void. The withdrawal of the Tang forces effectively reduced the geographic scope of the Tang Dynasty to the Chinese mainland, and only a thousand years later would Inner Asia come back under Chinese rule during the Qing Dynasty. As the imperial court struggled against Yan forces, it was forced to rely increasing upon regional warlords who were outside imperial control, but could mobilize the armies required to defeat the Yan. Many of these regional warlords would remain largely autonomous from the imperial center until the Tang’s final collapse in 907.10 The ultimate result of the rebellion was a far more inward looking, less cosmopolitan, and less grand Tang Dynasty.

Just as the An Lushan rebellion irrevocably altered the course of the Tang Dynasty, it had the most profound consequences for the Uyghur Khaganate to the north. As Yan forces approached Chang’an, the crown prince Li Heng fled to Lingwu in the northwest, in modern Ningxia province. There, he usurped the throne, declared himself Emperor Suzong, and established contact with the Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur.11 An alliance was formed, where the Uyghurs would intervene on behalf of the Tang, and spearhead the effort to retake Chang’an. In exchange the Uyghurs were allowed to sack the city and haul off all the goods and women they could take. In addition, Khagan Bayanchur was given an imperial princess to marry and trade terms were negotiated that were extremely favorable to the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs provided military assistance throughout the course of the rebellion, and afterwards the unequal relationship was maintained simply due to the Tang’s severe weakness. The Tang court continued to trade on unfavorable terms with Uyghurs out of fear, while the Uyghurs concluded it was more profitable to exploit the Tang through unequal trade terms than to raid and steal from it. The end result was the enormous enrichment of the Uyghur Khaganate.

The Origins of the Uyghur Khaganate

Historians believe the Uyghurs as a tribal grouping emerged following the collapse Xiongnu, the nomadic empire which ruled the steppes during the era of the Qin and Han Dynasties. The Uyghurs were merely one tribe amongst a larger grouping known as the Toquzoguz, a tribal ethnonym which simply means “nine tribes.”12 The Uyghurs were the royal, ruling clan of the Toquzoguz, with the eight other tribes being subordinate to them. The Uyghurs themselves were made up of ten clans and eight smaller families.13 The Turkic Khaganates were all structured around a royal tribe, inner tribes, and outer tribes. While the Khagans would come from the royal tribe, his wives, generals and high officials would be recruited from the inner tribes. During the Uyghur Khaganate the eight additional tribes within the Toquzoguz grouping would have served as the inner tribes.

From the mid-6th century onwards the Uyghurs were subordinate to the Turkic Khagans but regularly rebelled. Seemingly, the Uyghurs were one of their most recalcitrant subjects. Around 650, during the Second Turkic Khaganate period, the Yaghlaqar clan became leaders of Uyghur tribal grouping. By the 740’s the Second Khaganate was fracturing, and in 742 the Uyghurs, along with the Basmil and Karluk tribal groups, rebelled against the reigning Khagan. Immediately following the Khaganate’s collapse the three tribal allies turned on each other. First, the Uyghurs aligned with the Karluks to defeat the Basmils, who then fled southwest to Zungaria, modern day northern Xinjiang. The Uyghurs then defeated the Karluks, who fled to the Chu Valley in Semirechye, displacing the Turgesh Turks who previously ruled there. By 744 the Uyghurs had seized full control over the steppes of the Mongolian Plateau, and established the Uyghur Khaganate. The Khaganate’s capital of Ordubaliq (“city of the horde”), also known as Karabalghasun (“the black city”), was constructed along Chinese urban planning norms and was located in the Orkhon Valley, west of the modern Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar.

The Uyghur Khaganate was generally the same as the previous Turkic Khaganates, except for one significant difference. Under the previous Khaganates, the Khagans were required to be from the Ashina family and descendants of Bumin Ashina, the founder of the first Khaganate. Without an Ashina lineage, the Khagan would be seen as illegitimate and as usurper. Similar to the Romanovs in the Russian Empire or the Hapsburgs in the Austrian Empire, the Ashina were seen as being the sole legitimate rulers of the Turks. Yet, the Uyghur royal Yaghlaqar clan were not of Ashina family, and in the eyes of the other Turkic nomads, the Uyghurs led by the Yaghlaqars were illegitimate usurpers. The Yaghlaqar’s crisis of legitimacy was solved by the Uyghurs’ conversion to Manichaeism and their affiliation with the Sogdians.

The Turko-Sogdian Milieu

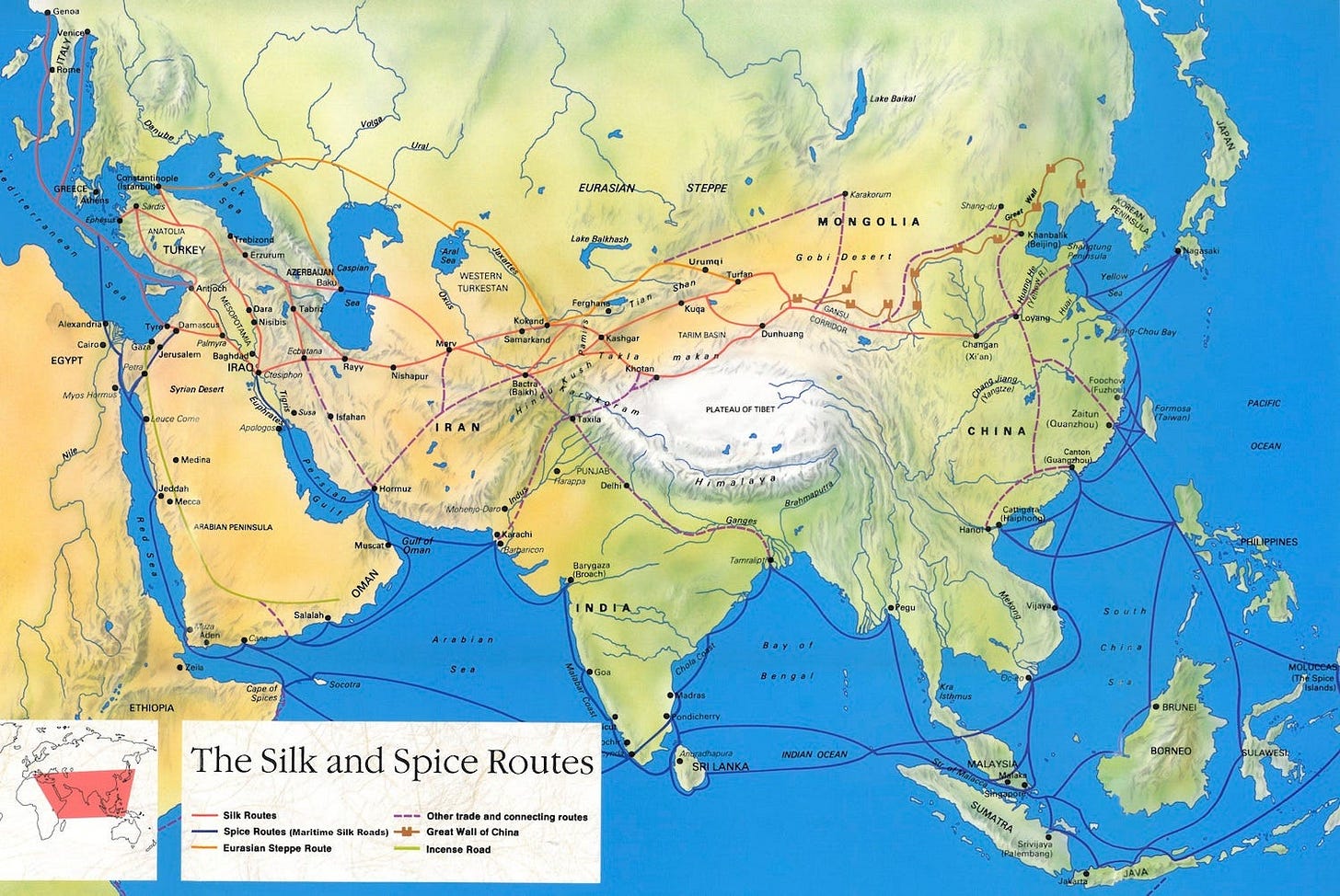

In the early medieval period, the Sogdians were the preeminent merchants on the Silk Road.14 Originally from Sogdia, the oasis cities of modern Uzbekistan such as Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara, beginning in the 5th century the Sogdians expanded eastwards. They founded colonies and created a diaspora network that stretched from their homeland in Central Asia to China. Similar as other “middleman minorities” such as the Jews, Armenians, Chinese Hakkas, Phoenicians in antiquity and Lebanese today, the Sogdians were able to leverage their diaspora networks and cosmopolitanism in order to manage long distance trade between different sedentary societies and the steppe nomadic world.15

The 6th and 7th centuries saw geopolitical revolutions in two opposite ends of Eurasia that fundamentally transformed the Sogdian world. The first was the rise of the Turks, and second was the rise of the Islamic Arabs. The Turkic Khaganate and its conquest of the Eurasian steppes created enormous opportunities for the Sogdians. With the steppes unified and peace established, long distance trade and commerce could be conducted without fear of robbery or extortion by either bandits or warring states. The Sogdians were already handling much of the long distance trade along the Silk Road, but with the establishment of the world spanning Turkic Empire, Sogdian commercial activity reached new heights. Turkic hegemony resulted in the flourishing of the Sogdians.

Also similar to the Jews in Europe and in the Islamic world, the Sogdians often served as state officials under the Turks due to their uniquely strong culture of literacy and cosmopolitanism. Sogdian involvement in state affairs was most commonly seen in diplomacy. For example, the first diplomatic contact between the Turks and Byzantium was established by the Sogdian Maniakh who visited Constantinople in 560’s.16 Maniakh served at the behest of the Western Turk leader, Yabgu Istemi.17 Naturally, it would have been very difficult for an empire ruled by illiterate, cultureless people to maintain diplomatic contact with China, Persia and Byzantium, all of whom had strong imperial traditions themselves. Thus as a result, the Sogdians came to fill a much needed niche as scribes, officials, and diplomats within the Turkic Khaganates. Likewise, Chinese were used as architects and craftsman, and all Turkic urban centers would be built in a grid layout similar to Chinese cities. The Sogdians and Chinese filled the same niches that Jews and Byzantines would have filled in the Khazar Khaganate that later emerged in the west contemporary with the Uyghur Khaganate. For more on the Khazars, see my introductory essay on the Khazar Khaganate.

The expansion of the Arabs into Central Asia proved to be far less lucrative for the Sogdians. The Arabs first penetrated into Central Asia in the mid-7th century, shortly after they conquered the Persian Sassanid Empire. Their initial incursions were largely raids and not very significant, but beginning in the 8th century the Arabs reentered the region much more forcefully. The Arabs now sought to conquer the region and bring the Sogdians firmly under their domination. As Arab control over the region was not firm, the Sogdians repeatedly rebelled, and in response the Arabs launched repeated punitive attacks on Sogdian cities which inflicted massive damage on them. Moreover, the Arab expansion into Sogdia prompted the intervention by the Turgesh, a Turkic tribal alliance based in Semirechye. The Arabs and Turgesh fought their wars across Sogdia, which only further devastated the region.18 The transformation of their homeland into warzone prompted a mass exodus of Sogdians eastwards to where they already had colonies and knew of opportunities in the Khaganate and in China. One of the many consequences of the Arab expansion into Central Asia was the deepening of Sogdian involvement in Turko-Chinese affairs.

The Sogdians also served as state officials in the various hybrid dynasties that had existed in northern China during the Han-Sui interregnum and extensively in the Tang Dynasty prior to the An Lushan Rebellion. Following such an intimate involvement by the Sogdians in Chinese and Turkic state affairs, a general Turko-Sogdian and Sino-Sogdian cultural fusion occurred that largely happened at elite levels. For example, as mentioned above, An Lushan was part Sogdian and Turkic, but he was hardly alone this. Throughout the Turkic Khaganates, Chinese dynasties, and the Tocharian city states of the Tarim Basin, the Sogdians intermixed extensively with locals, creating a hybridized Eurasian cultural milieu that was distinct to eastern Eurasia in the early middle ages.

The Uyghur Khaganate was merely the culmination of centuries of Turkic-Sogdian fusion. The Uyghur Khaganate likely had a significant Sogdian presence at its outset, but following the An Lushan Rebellion, Sogdian influence amongst the Uyghurs reached an unparalleled level not seen in any prior Khaganate.

The Manichean Uyghurs

As the An Lushan Rebellion dragged on, the Uyghurs intervened repeatedly on behalf of the Tang to help defeat the Yan rebels. Towards the end of the rebellion in 762, the Uyghurs recaptured Luoyang, the Tang’s second capital.19 There, Khagan Bögü encountered Sogdian Manichean priests, and under their influence in the ruins of Luoyang he converted to Manichaeism.20

The Manichaean faith was a gnostic, dualistic, Abrahamic religion that originated in the 3rd century in Mesopotamia.21 The religion’s founder was Mani, who was raised in an Elcesaite community, a Judeo-Christian sect that was founded by Jews who rejected the Passover sacrifice and instead accepted elements of Christianity. The Elcesaites believed fire was evil, and that water cleansed the sins of both animate and inanimate objects. They would ritually purify their food by washing it in water. Due to their unique dinning customs they would rarely eat food from outside of their community, nor could they eat with outsiders, resulting in an extremely inwardly looking sect.

The religion of Mani traced its theological genealogy back through Christ, Buddha Sakyamuni, Zoroaster and Moses. As a result, Manichaeism contained elements of Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, creating a highly syncretic religion. Manichaeism’s core theological belief was the existence of a dualistic struggle between light and matter. They believed in primordial times the evil “King of Darkness” had attacked the Land of Light, and entrapped the light within physical bodies. The Manicheans believed that upon death, the light would be released from physical entrapment and defilement, while sexual reproduction would continue the light’s entrapment. The faithful were divided between the “Elect” who maintained an ascetic lifestyle which forbid meat, sex, drinking wine, the use of fire, and all material processions, and “Hearers” who constituted the religion’s lay followers. The Elect believed in complete non-violence, even rejecting agriculture and farming as they believed “if a man reaps, he will be reaped.”22

Mani wrote his gospels in Syriac Aramaic, which was already present in Sogdia prior to the coming of Manichaeism as the Persian Achaemenid Empire had used Aramaic as its administrative linga franca.23 The Sogdians not only converted to Manichaeism, but also to Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Nestorian Christianity which also used the Syriac Aramaic script. And wherever the Sogdians went, they brought their religion with them. In relation to the Turks, the Sogdians were essential like bumblebees in how they cross-pollenated the illiterate, shamanist nomads with foreign customs and ideas that were more complex than what the Turks were use to.24 Not only were the Uyghurs converted to Manichaeism, but other tribes adopted Zoroastrianism and Nestorian Christianity from the Sogdians. The European medieval story of Prester John was likely based on rumors of Christianized Turkic nomads in Inner Asia who had converted due to the proselytizing efforts of Sogdian Christians.25

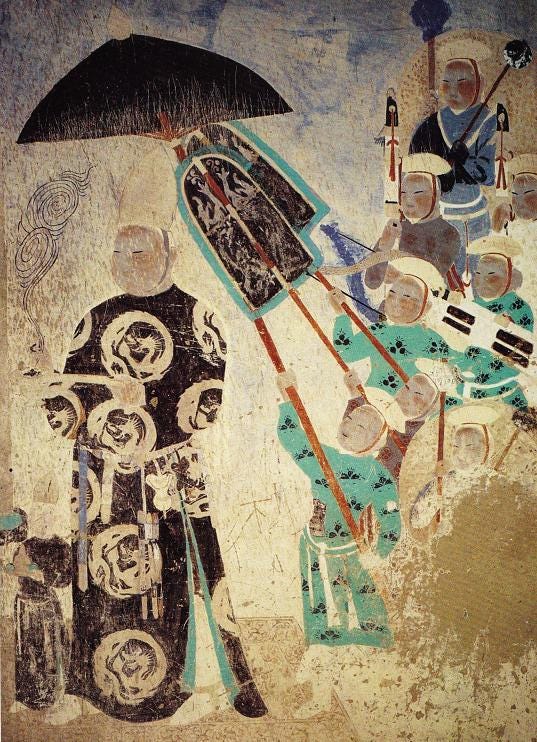

Upon returning to Ordubaliq, Khagan Bögü established Manichaeism as the Khaganate’s state religion. The conversion to Manichaeism inextricably linked the Uyghurs to the Manichaean Sogdians, tying the Khaganate to these Sogdians and their commercial networks. United in faith, the Manichaean Sogdians who resided in Tang China came under Uyghur sovereignty and protection. This alliance with the Manichean Sogdians brought enormous wealth to the Uyghurs, as the Sogdians served as their commercial agents in China, and served to integrate the Uyghur Khaganate into the trade flows of the Silk Road. These Sogdian not only negotiated on behalf of the Khaganate highly favorable trade terms with China, they also made the Uyghur Khaganate into the central commercial emporium in eastern Eurasia. The principle result of the Uyghurs’ conversion to Manichaeism was their massive enrichment.

The An Lushan Rebellion was as much a foreign invasion by barbarians as it was a rebellion, and while not all foreigners cooperated with An or rebelled, the connection was clear nevertheless.26 The rebellion was an inflection point in the history of the Tang Dynasty not only in terms of its power but as result of the rebellion the civic culture of the Tang shifted from being cosmopolitan, xenophilic even, to being decisively xenophobic. Following the rebellion’s resolution, the Tang state began persecuting Sogdians and other foreigners, but relented from attacking the Manichean Sogdians due to political pressure from the Uyghur Khaganate to the north.

Manichean temples that were forcefully closed were allowed to reopen due to Uyghur pressure. The Tang risked incurring the wrath of the Uyghurs if they had continued to target the Manichean Sogdians. A Uyghur invasion could very possibly have toppled the dynasty, and thus the Tang relented on targeting Manichean temples and the Sogdian faithful. For Uyghur Khaganate, legitimacy became based on defending the Manichean faith, which in practical terms meant the international diaspora network of Manichean Sogdian merchants. Through their proselytizing efforts, the Manichean Sogdians had effectively entered into a political-commercial alliance with the Uyghurs. The result of this partnership was their mutual enrichment at China’s expense.

The Enrichment of the Uyghurs and the Looting of China

In exchange for the Uyghur’s intervention, the Tang agreed to significant political and commercial concessions. New terms of trade were agreed to which greatly favored the Uyghurs, and these terms remained fixed following the resolution of the rebellion. As the Uyghurs enjoyed greater power and prestige than any Turkic Khaganate prior, and as the Tang remained crippled, the Tang court was not in a position to renegotiate commercial relations.

It is important to note that foreign policies of Chinese dynasties were often formulated and phrased in a manner quite distinct from how modern states speak about their foreign relations. Today states speak about their foreign policies as either being based on transactions or morality. By contrast, imperial China spoke of its policies with a tone of reciprocity, familial hierarchy, and the ever present sense that China was the central hegemon, even if in actual power political terms they were not. From the An Lushan rebellion onwards, the Tang gave the Uyghurs enormous concessions all phrased in a face-saving manner that masked the real power relations between the two. The Uyghurs were given “gifts in return for assistance”, the most important being three imperial Tang princess that were married off to Uyghur Khagans between 756 and 840. Marriages to these princesses not only gave the Uyghur Khagans immense prestige, but also came with enormous dowries that the Tang court paid to the Uyghurs.27

The Uyghurs were also given the opportunity send missions to Chang’an “rendering tribute.” In reality, it was the Tang court giving tribute to the Uyghurs. Officially the Uyghurs would come to give tribute, but effectively they were trade missions dressed in state pomp, and of course, the terms of trade were extremely favorable to the Uyghurs. Additionally, the members of the mission were given official titles and salaries. Between 745 and 840, the Uyghurs conducted 116 of these “rendering tribute” missions to Chang’an.28

The Tang withdrawal from the west had the additional consequence of the loss of the dynasty’s best pasture lands. The Tang’s power largely lay in its cavalry force, as infantry lacked the mobility to effectively combat the Tang’s Turkic and Tibetan rivals with their cavalry centric armies. South the Great Wall, China generally lacked pasture lands that could sustain a massive cavalry force.29 First, China’s land was largely utilized for farming. Secondly, its soil generally lacked the same nutrients as land in the steppes, the result being that horses raised in China were smaller and weaker than horses from the steppes. Due to these ecological conditions Chinese dynasties were often dependent on their nomadic rivals to supply them with horse. What was decisive in these trade relations was the relative balance of power between China and the nomads, as this factor would determine the terms of trade. Unlike other smaller dynasties such as the Song or Ming, the Tang prior to 755 controlled many excellent pasture lands beyond the Great Wall frontier, namely in the modern day provinces of Gansu and Qinghai.30 But as these pasture lands were lost to the Tibetans after 755, the Tang were that much more dependent upon the Uyghurs for their supply of horses.31

Tang-Uyghur trade was largely centered on horses for silk, with the later serving as a form of currency along the Silk Road at the time. Before the rebellion, the Tang would pay 25 bolts of silk per horse. After 755, the Sogdians were able to take advantage of the Tang’s beleaguered condition and negotiated new, and more favorable, terms of trade on behalf of the Uyghurs. The price per horse was raised from the traditional 25 bolts of silk to 40 bolts per horse.32 33 Following the renegotiated trade terms set during the rebellion, the Uyghurs sold Tang China around 7,500 horses annually, in exchange for 300,000 bolts of silk. Tang China’s enormous silk payments to the Uyghurs were even noted by Tamim ibn Bahr, a Samanid envoy who visited Ordubaliq in 821.34 According to Tang sources, the Uyghurs would often sell them inferior quality horses, but again, due to the Tang’s weakness they were hesitant to protest.35 36 The immense burden of putting down the An Lushan Rebellion, combined with the unequal trade terms with the Uyghurs, Tang finances were bleed dry. For decades after the rebellion the court had difficulty in paying the salaries of court officials.

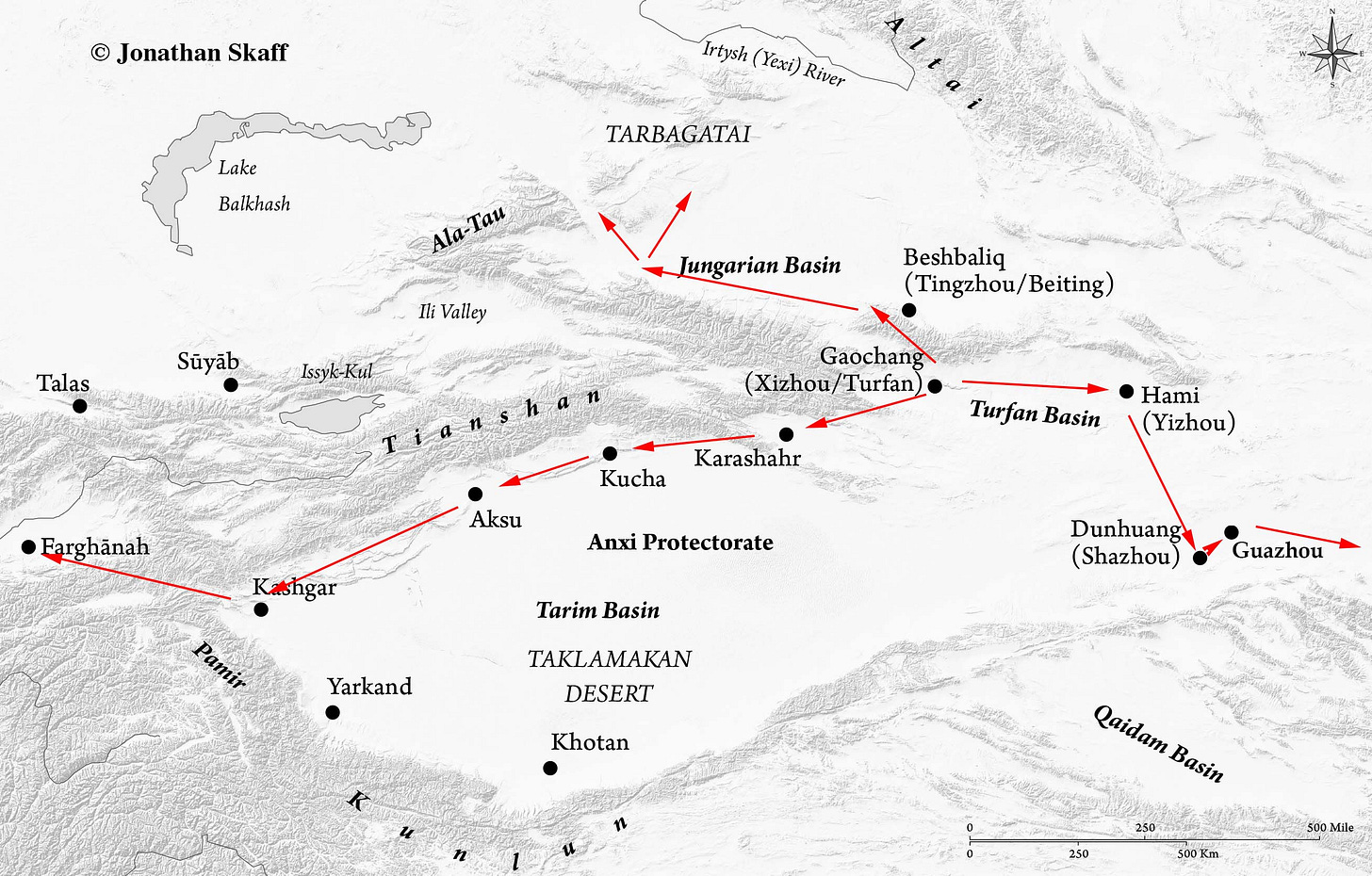

The Manichean Sogdians also rerouted their commercial networks to transit through the Uyghur Khaganate. Prior to the An Lushan Rebellion, most trade routes ran west from Chang’an through the Hexi Corridor, then continuing across the Tarim Basin either along its southern or northern edge, or going north towards the Turfan Depression and continuing along the northern face of the Tianshan Mountains. As Tang forces withdrew from the West in order to combat the Yan rebels, the entire length of the Silk Road from the Yellow River to the Pamir Mountains was occupied by the Tibetans, and later became a warzone as the Tibetan-Uyghur conflict intensified.37 As security deteriorated along the Hexi-Tarim route, trade routes shifted northwards, running from China towards the Uyghur Khaganate on the Mongolia Plateau, and then turning west and continuing along the steppes through Zungaria, between the Tianshan and Altai Mountains. As the Manichean Sogdians knew they could rely on the Uyghurs for protection, there was the double incentive for merchants to travel through the Khaganate instead of taking the risker routes to the south. With caravans being redirected northwards, the Uyghurs were able to tax all transitory trade between China and the rest of Eurasia.38

Resolving to the Yaghlaqar’s Crisis of Legitimacy

This massive influx of wealth, provide by the Uyghurs’ conversion to Manichaeism and their affiliation with the Sogdians more broadly served to overcome the Yaghlaqar’s crisis of legitimacy. As stated above, the Yaghlaqars were not Ashina Turks, and thus lacked the historic connection to the founder of the First Turkic Khagan, Bumin Ashina. Without this connection, the Yaghlaqars had no moral claim to the title of Khagan, nor the right to claim hegemony over the other Turks. Nevertheless, they overthrew the Second Turkic Khaganate, defeated their erstwhile Karluk and Basmil allies, crushed all other rivals, and even came to dominate the Tang Dynasty. While the Yaghlaqars might have lacked moral legitimacy, they certainly had enormous power. Yet, in order to established a lasting political order, two things are required, power and legitimacy.39 Power is of course necessary to impose your will upon others, especially those who are extremely recalcitrant, but power and the use of force can only go so far. The state cannot be maintained solely by coercion, it needs the cooperation of its subjects, and this cooperation will only be given if they view the state as being legitimate.40

For a state such as a Khaganate, cooperation is especially needed from tribal leaders. Without the cooperation from the tribal leaders, they will simply defect from the Khaganate and migrate away. For example, in the 17th century the Mongolic Torghut tribe defected from the Oirat Confederacy, also known as the Western Mongols. The Torghuts were dissatisfied with the state of things, and migrated from Zungaria all the way to the steppes just south of the Volga River. There, they became known as the Kalmyks, and eventually came under Russian Tsarist control. The Kalmyks eventually became dissatisfied with Russian rule, and after a century of living near the Volga, a large contingent of Kalmyks migrated back eastwards to Zungaria.41 As can be seen, the high degree of mobility made the nomads especially difficult to control. In fact, despite the Khaganate being a nominally autocratic, authoritarian state, it depended on a sense of legitimacy and elite cooperation more so than other empires did, such as the Roman or the Russian empires. After all, a rebellious city or region could not simply up root itself and migrate away as a nomadic tribe could, or at least not as easily.

Of course, the Khaganate needed more than just Ashina leadership to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of the Turks. What principally held a steppe nomadic state together were promises of wealth for its followers and warriors. In this sense, a Khaganate was essentially a giant piratical organization, organized to extract wealth from neighboring sedentary societies. The nomads would either raid and physically seize the wealth, or intimidate the sedentary society’s government and force them to give the nomads tribute. This is not radically different from a mafia organization demanding protection money. Tribal leaders were effectively warlords, and the ability to deliver wealth to their followers would attract to them more followers. With more followers, they would be that much more capable of effectively raiding or intimidating the neighboring sedentary society. Thus, a snowball effect would occur, where a charismatic warlord with a proven track record of success could come to process an army and an empire. What held a union of nomadic tribes together was not ideology or religion, but promises of wealth.

Thus it can be seen that nomadic empires were essentially functioned as parasitical organisms that leeched off of nearby sedentary societies. For the Turks and other nomadic peoples who inhabited the eastern Eurasian steppes, the primary target for exploitation would naturally be China. Thomas Barfield goes so far to argue that the rise of steppe nomadic empires was dependent upon a unified China to exploit, as only a unified China could mobilize a sufficient amount of wealth for the nomads to extract that would allow them to snowball into an empire themselves.42

But why were the Sogdians instrumental in allowing the Uyghurs to overcome their lack of legitimacy? The Sogdians helped the Uyghurs exploit China to fullest possible extent. By converting to Manichaeism, the Uyghurs made themselves partners with the Manichaean Sogdians, and through these Sogdians the Uyghur achieved unparalleled amounts of wealth. As stated above, the Sogdians negotiated highly favorable terms of trade on behalf of the Uyghurs and the Sogdians redirected their caravan trade routes through the Khaganate. In short, the Uyghurs piggybacked on the commercial networks managed by the Manichean Sogdians, and engorged themselves on the wealth that flowed through them. Thanks to their affiliation with the Manichean Sogdian, the Turks extracted more wealth from China than ever before, far more than what had been realized during the First or Second Khaganates. As the Turks came to enjoy all this wealth, the fact that their Uyghur rulers were led by the Yaghlaqars and not by the Ashina clan became less important. In other words, the Uyghur compensated for their lack of Ashina lineage by providing the Turkic tribes with unparalleled wealth. Even more simply put, the Uyghurs bribed the other Turks to simply not care.

It should also be considered that the Sogdians served an additional, and much simpler, purpose in helping the Yaghlaqars overcoming their crisis of legitimacy. Simply, the Yaghlaqars could put their complete trust in the Manichean Sogdians. By contrast, the political loyalties of the Turks not within the Toguzoguz tribal union would always be suspect.

The problem that the Yaghlaqars faced was that they were seen as usurpers, and therefore doubts to their legitimacy as rulers of a Turkic Khaganate would have always hung over their heads like the sword of Damocles. One could even say, the Yaghlaqars’ lack of an Ashina lineage was the original sin of the Uyghur Khaganate. As detailed above, the Yaghlaqars solution to this problem was to effectively bribe the Turks and purchase their loyalty, or at least ensure their complacency. But of course, this does not completely resolve the problem but merely paper over it. No matter how much wealth the Yaghlaqars brought to the Turks, this fundamental problem concerning their legitimacy would always remain.

To better understand this crucial dynamic to the inner workings of the Yaghlaqar regime, let us turn to ancient Greek political thinking. Using Aristotle’s categorization of regime type as laid out in his “Politics”, the Uyghur Khaganate can be understood to be a tyranny, while the preceding Turkic Khaganates were monarchies. According to Aristotle, a tyranny is a deviation from monarchy. While a monarch rules over willing subjects, a tyrant rules over unwilling subjects.43 What characterizes a monarchy and kingship is that the ruler is selected for his outstanding virtue, of which he has more than anyone else in the community.44 A king in a monarchy, while autocratic, nevertheless rules with a degree of popular consent, and instead of relying on force or other means, his regime stands upon his moral virtue.45 A tyrant by contrast: “looks to nothing common, unless it is for the sake of private benefit. The tyrant’s goal is pleasure; the goal of a king is the noble. Hence, of the objects of aggrandizement, material goods are characteristic of tyranny, while what pertains to honor is characteristic of kingship.”46

Using the king/tyrant dichotomy provided to us by Aristotle, we can see the First and Second Turkic Khaganates, led by the Ashina clan, were monarchies, while the Uyghur Khaganate was a tyranny. Bumin Ashina, founder of the First Khaganate, was deemed the most virtuous as he led the Turks to victory over the Rouran and established their state, while his descendants ruled upon a hereditary principle. The Yaghlaqar clan by contrast, based their rule on lavishing wealth upon their subject, in order to compensate for the fact that they were not the traditionally legitimate rulers of the Turks. Aristotle’s observation, that tyranny represents an ultimate version of democracy can also be seen in the Uyghur Khaganate.47 Just how an extreme democracy panders to the people and seeks to gain their favor, a tyranny must do the same in order to garner support and legitimacy for the regime. The Uyghurs enriched the Turks in order to gain their support, or in other words, they effectively bribed the people in a manner similar to how Caesar reduced the plebeians’ debts when he was dictator. Thus, the Uyghur usurpation can be seen to represent a transition from monarchy to tyranny within the Turkic Khaganal tradition.48

Now that it has been established that the Uyghur Khaganate was a tyranny, what the primarily purpose of the Sogdians was for the Yaghlaqars can be understood. The Manichaean Sogdians represented an element within the state that the Yaghlaqars could trust and rely upon fully. This is because the status the Manichean Sogdians enjoyed within the Khaganate was wholly dependent upon the Yaghlaqars. The Yaghlaqars understood that without them, the Manichean Sogdians would have nothing. Their homeland was being ravaged by the Muslims, who had a particular displeasure towards Manichaeism, and the Tang Dynasty had turned extremely hostile to them following the An Lushan Rebellion. Without Uyghur protection, their communities in China would be uprooted and eradicated, and their commercial networks would disintegrate. All of this would have been obvious to the Yaghlaqars, and thus they were guaranteed of the Manichean Sogdians’ loyalty to them and their regime.

A tyrant’s distrust of his own citizens and the use of foreigners to prop up his regime was a well-known phenomenon among Greek political thinkers, Aristotle among several others. To quote Aristotle, “It is also characteristic of the tyrant to have foreigners rather than persons from the city as companions for dining and entertainment, the assumption being that the latter are enemies, while the former do not act as rivals.”49 As a tyrant mistrusts his own people and fears he lacks their support, he comes to rely on foreigners in order to consolidate his rule, as the foreigners will be wholly dependent on him.

Xenophon points this out in his dialogue “Hiero the Tyrant.” Hiero speaking to Simonides says, “The point is that he doesn’t like to develop combativeness and military skills in the citizens in his state; it gives him greater pleasure to make his foreign militia a more formidable fighting force than his fellow countrymen and to use them as his personal guard.”50 In “The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers” by Diogenes Laërtius, Solon, speaking to Periander, said nearly the same as Xenophon speaking through Hiero. Solon says, “But if you absolutely must be tyrant, then you better provide for having a foreign force in the city superior to that the citizens.”51 Aristotle likewise acknowledges the tyrant’s reliance on foreigners, “citizens guard kings with their own arms, while a foreign element guards the tyrant, since the former rule willing persons in accordance with law, while the latter rule unwilling persons. So the ones have a bodyguard provided by the citizens, the others one that is directed against them.”52 While Sogdians did not serve as body guards or as soldiers within the Khaganate, the utility was nevertheless the same. The Sogdians represented a foreign contingent that was wholly dependent on the Yaghlaqars for their status, and thus the Yaghlaqars could trust them not to overthrow the reigning regime.

The Yaghlaqars utilization of the Sogdians to overcome their crisis of legitimacy proved highly successful. Not only did the Yaghlaqars prevent any Ashina revival or internal insurrection, they created a highly prosperous, extremely powerful state. While documentary evidence is scarce, it appears that after 762 the Uyghur Khaganate replaced the Tang Dynasty as the center of gravity in Eurasia and the Silk Road. Yet, the enormous enrichment of the Turks did not have a positive long term consequences on the Khaganate. The Yaghlaqars’ successful resolution of one crisis created a new problem. The Uyghur elite used their newly found wealth to trade the harsh life of nomadic wandering in tents for the pleasures of urban life, but as a consequence of this change they lost their ‘barbarian virtues’ and what had made them great. The Uyghur Khaganate suffered a similar fate as the Roman Empire, as understood by Gibbon. Both states succumbed to decadence and lost their virtues.53 Nor is this surprising, warlike peoples have are prone to over indulgence in luxury, as Aristotle notes, Ares and Aphrodite are often paired.54

The Domestication and Decadence of the Uyghurs

The immense wealth accumulated by the Uyghurs had the principle effect of making them partially sedentarized. After all, it is far more difficult to be regularly on the move and nomadize if you are encumbered with so many material possessions. In order to have a simpler life and to better enjoy their wealth, the Uyghurs built their grand capital of Ordubaliq in the Orkhon Valley, and their secondary capital of Baybaliq in the Selenga Valley.55 According to archeological findings, the walled enclosure of Ordubaliq was 33km2, roughly the same size as the Tang capital of Chang’an. While certainly not as densely populated as Chang’an, a large portion of the Khaganate’s approximate 800,000 inhabitants lived there, with an even larger portion of the khaganate’s wealth was stored there as well.56

As mentioned above, the only surviving firsthand account of Ordubaliq comes down to us from the Samanid envoy Tamim ibn Bahr. Bahr describes the Uyghur capital as such: “He reports that this is a great town, rich in agriculture and surrounded by rustaqs full of cultivation and villages lying close together. The town has twelve iron gates of huge size. The town in populous and thickly crowded and has markets and various trades. Among its population, the Zindiq (Manichean) religion prevails.”57

The most noteworthy pieces of information in Bahr’s account are the references to the extensive agriculture surrounding the city, the city being “thickly crowded,” and its twelve giant gates. Clearly, Ordubaliq was far from being a temporary nomadic camp, but instead a major urban center that would have resembled any other capital city of a sedentary civilization. The reference to extensive agriculture is particularly important. As hegemony had been established on the steppes and what enemies the Uyghurs had were far away, agriculture was made possible. The importance of this is less so the changes it might have had on the Uyghur’s diet. In all likelihood, Uyghurs retained the traditional steppe nomadic diet of mostly dairy and meat. Instead, agriculture production was likely meant to feed to the new inhabitants of Ordubaliq.

The wealth of the Uyghurs almost certainly attracted many craftsmen, merchants, entertainers and other such people that would be found in any other major urban center at the time. These people would have come from China, Sogdia, Siberia, the Tarim Basin’s city states and elsewhere. As the Tang declined, many who had once plied their services in Chang’an likely relocated to the far richer and more vibrant Uyghur capital. For example, as the Tang became decisively xenophobic, many the Kuchean dancers that were once very popular among the Chang’an elite likely chose to relocate to Ordubaliq where potential patrons were wealthier and the political climate more welcoming. Ordubaliq likely developed a “floating world”58 comparable to what existed in Chang’an prior to its great calamity, and it can easily be imagined that the once poor and uncultured Uyghurs would have been even more enamored with such entertainment than the Tang had been under the Emperor Xuanzong. The effects this had on the Uyghur’s virtues and moral character are difficult to determine. More importantly, it meant that Uyghur power was now anchored in a fixed urban center with a large population that was dependent on agricultural supplies. This development completely negated the traditional nomadic advantage of mobility.59

The partial sedentarization of the Uyghur elite and their core followers in their capital of Ordubaliq ultimately doomed the Khaganate. The most immediate change would have been a general softening of the Uyghurs. No longer living on the harsh steppes in tents, but instead enjoying the pleasures and comforts of urban life, the Uyghurs would surely have declined as a martial people. Sedentarization not only resulted in the loss of their ‘barbarian virtues’, but it also created a fixed, immobile, and alluring target for the predatory tribes that remained beyond the Uyghur’s control. The mobility of the nomads was their greatest assets. Their lifestyle was inherently mobile, and their wealth largely lay in their animals which could be herded with relative ease. If they were ever threatened, nomads could simply withdraw as the Scythians or Mongols famously did when being attacked by the Persians and Chinese. The only piece of territory the nomadic Scythians and Turks would defend were their royal tombs. The creation of a large, wealthy urban center on the steppes changed this dynamic.

In an ironic twist of fate, by the mid-9th century the Uyghur Khaganate became the decadent and feckless empire just as the Tang Dynasty had once been. Just as how the Tang Dynasty suffered a cataclysm at its imperial apogee, so would the Uyghurs. But unlike the Tang who survived in a crippled state for nearly another 150 years, the catastrophe that befell the Uyghurs completely annihilated their empire on the steppes. Ordubaliq came to resemble Constantinople on the other side of Eurasia. The opulently wealthy capital of Constantinople whetted the appetites of barbarian tribes beyond the imperial frontiers, and as a result the Byzantines regularly found themselves at the mercy of predatory nomadic hordes, all seeking to loot the greatest target that existed in western Eurasia.60 But unlike Constantinople which was located on an easily defended peninsula and guarded by the Theodosian Walls, Ordubaliq was vastly more vulnerable.

What the consequences of sedentarization would have been on the Uyghurs was hardly unknown them. By the 9th century the Turks had ruled the steppes for over 200 years and the Uyghurs could look back on the history of two previous Khaganates, their extensive dealings with China and their rise and fall. The course taken by the Uyghur Khaganate had been warned against already. The fourth Khagan of the Second Khaganate, Bilge Khagan had warned against of Sinicization.61 His warning survives as an inscription on a stele that was made during his lifetime, and later discovered by archeologists in the Orkhon Valley. Bilge Khagan’s inscription says:

“The words of the Chinese people have always been sweet and the silks of the Chinese people have always been soft. Deceiving by means of their sweet words and soft silks, the Chinese are said to cause the remote peoples to come close in this manner. After such a people have settled close to them, the Chinese are said to plan their ill will there. … Having been taken in by their sweet words and soft materials, you Turkic people, were killed in great numbers. O Turkic peoples, you will die! … unwise people went close to the Chinese and were killed in great numbers. …If you stay at the Otuken Mountains, you will live forever dominating the tribes! … If you once become satiated, you do not think of being hungry again.”62

For the nomads on the steppe “becoming Chinese” was practically a synonym for sedentarization. As mentioned above, cities on the steppe were built in a Chinese manner. Similar as how modernization today essentially results in Americanization, sedentarization was the equivalent to Sinification simply because of China’s overwhelming material and cultural dominance. More generally, China and the steppe nomads defined themselves against the other’s way of life. The nomads disdained the dreary serfdom of agricultural live, while Chinese disdained the rootless wanderings of the nomads on the steppe.

Tonyukuk, who served as a Tarkhan, or general, under Bilge Khagan gave an even more blunt warning:

Tonykuk issued this warning in response to Bilge Khagan’s interest in converting to Buddhism and building temples. It is worth noting that nearly 1000 years later, the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty would promote Tibetan Buddhism among Mongolians in order to tie tribes to fixed locations on the steppe.

The Uyghur’s partial sedentarization did not result in China attacking as Bilge Khagan had forewarned, but instead another more ‘barbarian’ people took advantage of the Uyghur’s laxness.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz

The Yenisei Kyrgyz lived northwest of the Uyghur Khaganate, in the Yenisei Valley and the Minusinsk Basin in southern Siberia, namely in the modern day regions of Khakassia and Krasnoyarsk Krai in Russia.63 Reportedly, the land of the Yenisei Kyrgyz was 40 days by caravan from Ordubaliq, a journey which involved crossing the Khangai and Sayan Mountains in the northwest of the Mongolian Plateau. Only semi-nomadic, the Yenisei Kyrgyz lived in wooden houses in the winter and then nomadize during the summertime in tents. They practiced both pastoral husbandry and limited agriculture. They reportedly had one city where the Yenisei Kyrgyz lived, but its location is completely unknown, and so is the existence of any other towns or settlements they might have had.

According to Chinese sources, the Yenisei Kyrgyz believed themselves to be descendants of a spirit and a cow. More concretely, it is believed they spoke a Samoyedic language, which is a branch of the Uralic language family. During the Turkic Khaganates, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were partially Turkicized, as indicated by inscriptions dated from the 8th century found near the Yenisei River.64 Turkic likely served as a linga franca, but not the commonly spoken language. The Yenisei Kyrgyz were largely Caucasian in appearance, with some having Asiatic features. According to Tang Dynasty sources, the Kyrgyz were tall with red hair, white faces, and green or blue eyes.65 Tibetan sources from the 8th century also mention the Yenisei Kyrgyz has having blue eyes, while texts from the Ghaznavids say the Kyrgyz look like the Slavs.66 Some Kyrgyz had black hair, but this was considered to be unlucky. The Kyrgyz believed those with dark colored hair and eyes to be descendants of Li Ling, a Han Dynasty general from the first century BC who defected to the Xiongnu and then was sent by the Xiongnu ruler to the Yenisei Kyrgyz as an official to supervise them, and then later married a Kyrgyz woman.67

The Yenisei inscriptions mentioned above made references to Tengri, the same supreme deity the Turks worshiped. It is also known the Yenisei Kyrgyz worshiped water, grass, trees, wind, fire, and various animals including hedgehogs, oxen, falcons, and birds, also trees and the wind. For burials they cremated their dead.68 During the Uyghur era, some Sogdians attempted to convert the Kyrgyz to Manichaeism, but they were met with little success. The Yenisei Kyrgyz likely had little interest in a religion that would bring them closer to the Uyghurs, who they were actively trying to differentiate themselves from.

Despite periods of overlordship, the Turks never fully subdued the Yenisei Kyrgyz. The Kyrgyz were able to regularly rebel and effectively resist Turkic control thanks in part to their remote geographic region beyond the Sayan Mountain in Siberia, and also thanks to their extensive metallurgy production necessary for both amour and weapons. The Yenisei Kyrgyz initially came under Turkic rule around the 560’s, shortly after the founding of the first Khaganate. Following the Tang’s victory over Turks in 630, the Kyrgyz gained autonomy and opened diplomatic contacts with the Tang. As Turkic power reconstituted itself in 682, the Kyrgyz were once again subordinated under the Khaganate. A Kyrgyz rebellion was defeated in 710, with the would-be Kyrgyz Khagan dying in battle.

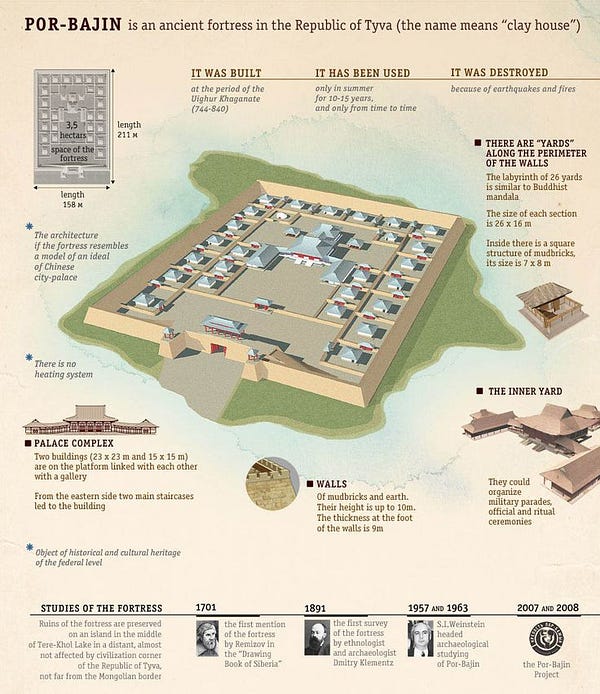

The Kyrgyz regained independence again following the Second Turkic Khaganate’s collapse in 742, but were soon after conquered by the Uyghurs in 758.69 Yet, the Kyrgyz were not defeated decisively, and were able to maintain a degree of autonomy, including the ability to conduct independent foreign relations with the Karluks, Tibetans and Arabs, but were prevented from making contact with Tang China. In 795, the Uyghurs had to fight the Kyrgyz again to reaffirm their control, and in the process killed the Kyrgyz ruler. During this period the Uyghurs built extensive fortifications in the Sayan Mountains, near the source of the Yenisei River in modern day Tuva, in order to defend against the Kyrgyz. The most famous of these sites is Por-Borzhan, a walled settlement located on an island in Lake Tere-Khol.

In 820 the Kyrgyz renewed their attempts to throw off Uyghur overlordship. The Kyrgyz ruler declared himself a Khagan, which not only signaled independence but also challenged the Uyghur’s status as sole hegemon over the steppes.70 Thanks to factionalism within the Uyghur court and Yenisei Kyrgyz’s alliance with the Karluks, the Uyghurs were unable to put down the revolt.

The Downfall of the Uyghurs and the Destruction of Ordubaliq

The Uyghur court had been long beset by severe factionalism and infighting. The details of what caused the infighting are not known, but the overwhelming influence of the Sogdians appears to have been the fault line. The first significant outbreak of internal turmoil occurred in 779 following the death of the Tang Emperor Daizong. The Sogdian advisors to the reigning Khagan Bögü advocated for an attack on the Tang Dynasty in order to take advantage of Daizong’s death and catch the Tang court when they were unbalanced.71 Khagan Bögü agreed to this, and ordered the Khaganate’s armies to advance towards the Chinese frontier. The Khagan’s chief minister Tarkhan72 Tun Baga, who was also his uncle, strongly opposed this and attempted to dissuade the Khagan from his planned war on China. According to Tang sources, the Tun Baga argued that the Tang had been friendly with the Uyghurs and that victory was not guaranteed, while a defeat could be catastrophic.73 The actual reasons for Tun Baga’s dissent were likely somewhat different, but it is impossible to know this for certain, nor what exactly his actual views were. What can be speculated is that Tun Baga represented a fraction within the Uyghur court who strongly opposed the Manichean Sogdians who had rapidly gained power within the Khaganate.74 Possibly, Tun Baga feared that Manicheanization would have similar consequences for the Uyghurs as Sincization as would, as their growing material wealth was all coming from China. As the material life of the Uyghurs became increasingly Chinese in origin, they risked becoming Chinese by extension and sedentarize.

Unable to argue the Khagan out of his decision, Tun Baga instead killed Khagan Bögü and 2000 of his closest followers, including his family, his clique and his Sogdian advisors.75 Tun Baga then assumed the role of Khagan with the throne name Alp Qutlugh Bilge. The anti-Manichaean faction ruled for the next decade. Khagan Alp Qutlugh Bilge died in 789 and was succeeded by his younger brother, Khagan Külüg, but he was killed a year later by his brother who then usurped the throne. Political instability continued within the Khaganate and only worsened into the 820’s and 830’s. As mentioned above, Uyghur factionalism gave breathing room to the Yenisei Kyrgyz, allowing them to mount a successful bid for independence. From 820 onwards the Uyghur and Kyrgyz were locked in continuous warfare. In 833, the reigning Khagan Zhaoli was murdered by his ministers and replaced by his younger brother, Khagan Zhangxin.76 77

In 839, Khagan Zhangxin discovered that several of his ministers were plotting to overthrow him. He ordered them to be executed, but another of his ministers named Kürebir sought vengeance and mobilized the Shatuo Turks to his cause.78 What begun merely as court intrigue had spiraled into a tribal revolt headed by a court fraction.79 Kürebir order the Shatuo Turks to surround the Khagan, which prompted the Khagan to committing suicide. Kürebir then installed Hesa as Khagan, with the throne name Kasar.80 In response to Kürebir’s actions, the Uyghur general Külüg Bagha fled to the Yenisei Kyrgyz. What exactly motivated Külüg Bagha is unknown, but presumably he was a part of the fraction linked to the former Khagan Zhangxin that had recently been deposed and wanted revenge.

The fortunes of the Khaganate only worsened as the winter of 839/840 was especially harsh. A deep freeze in conjunction with an epizootic outbreak decimated the Khaganate’s herds.81 Not only did this have negative economic ramifications, it would have also served to delegitimize the recently installed Kasar Khagan. Unfavorable climatic conditions following particularly severe political infighting would surely have been interpreted as a loss of “qut.”82 Qut was the Turkic concept of divine, heaven sent charisma which was embodied within the Khagan and extended over the entire state. Very similar to the Chinese concept of the “mandate of heaven,” political instability and natural disasters were seen as Heaven’s displeasure with the reigning temporal state. The loss of qut, or the mandate of Heaven, was tantamount to the state’s loss of legitimacy in the eyes of the Turks and Chinese.

With the Khaganate already severely weakened, Külüg Bagha returned to Ordubaliq leading a force of 100,000 Yenisei Kyrgyz sometime around February in 840.83 As it is told in the sources, Külüg Bagha and his Kyrgyz allies seemingly struck out of the blue, annihilating the Uyghur capital of Ordubaliq and with it the Khaganate as a unified political entity in single strike. In the course of the conflagration both Kürebir and Kasar Khagan died, and the Taihe Princess was captured by the Kyrgyz. The Taihe Princess was the daughter of Emperor Xianzong84 and was married to the Uyghur Khagan Chongde in 821.85 As will be seen later, the Taihe Princess would later play a major role in the fate of the Uyghurs who fled towards the Chinese frontier.

The downfall of the Uyghur Khaganate is recorded in the Hsin Tang-shu, or “New Tang History” as such: “Just that year, there was a famine and pestilence, and also heavy snowfalls. Many of the sheep and horses died. …. Wu-tsung86 ascended the throne and the heir-designate of the Prince of Tse, Yung, went to announce the fact to the Uighurs. He thus found out about the disorder of their state. Before long, the great chief Chü-lu mo-hu,87 together with the Kirghiz, brought together 100,000 cavalry and attacked the Uighur fortress, killed the Khagan, executed Chüeh-lo-wu88 and set fire to their royal camp. All the tribes scattered.”89

Practically overnight the Uyghurs went from being the greatest power in Inner Asia, dominating the Tang Dynasty and all the nomads of the steppe, to refugees scattered to the wind. The Uyghur Khaganate at the time of its collapse had an estimated population of around 800,000.90 91 The Yenisei Kyrgyz’s destruction of Ordubaliq resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands, and the panicked flight of those who survived. Those who were not killed during the initial Kyrgyz attack were hunted and pursued for years afterwards by the Yenisei Kyrgyz.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz’s destruction of Ordubaliq and the Uyghur Khaganate broke three centuries of continual Turkic imperial hegemony on the Eurasian steppes. A tradition that began with Bumin Ashina’s revolt against the Rouran and the founding the first Turkic Khaganate in the 6th century came to end with Manichean Uyghurs fleeing from the Samoyedic, semi-nomadic Yenisei Kyrgyz. The victory of the Kyrgyz and defeat of the Uyghurs was nothing less than a geopolitical revolution comparable to collapse of the Roman Empire. While the Turkic Empire had fallen, its legacy elsewhere throughout the world would be enormous. For more than a millennium afterwards peoples and countries would name themselves “Turk” just as others styled themselves as “Roman.”

In the short term, the breaking of Turkic power on the steppes allowed for the rise of the Manchurians. In the following five centuries, the semi-nomadic, partially Sinicized Manchurian peoples would establish several states which within over northern China and Central Asia, such as the Liao Dynasty, Western Liao (also known as the Kara-Khitan), and the Jurchen Jin Dynasty. The steppes of the Mongolian Plateau remained chaotic and disorganized, and would only be reunified five centuries later by Temujin, better known as Chingiz Khan. In the end, Mongolic speakers replaced Turkic speakers on the territory of modern day Mongolia. The Yenisei Kyrgyz’s victory over the Uyghurs represented the defeat of three centuries of Turkic hegemony on the Eurasian steppes, and the ultimately resulted in the Turks losing their homeland.

The remainder of this essay will examine the fate of the Uyghurs who fled from the Yenisei Kyrgyz, migrating off the Mongolian Plateau and went south. The story of the Uyghurs as refugees and their establishment of new states along the Silk Road are just as important as the history of their Khaganate. But first before proceeding, we shall remain with the Yenisei Kyrgyz for just a bit longer.

The Elusive Empire of the Yenisei Kyrgyz

Despite their total victory over the Uyghurs, at seemingly little cost, the Yenisei Kyrgyz did not establish an empire of their own the Mongolian steppes. Nor did they make any effort to occupy the Orkhon Valley, which was both the sacral and functional core territory of the prior Turkic and Uyghur Khaganates.

Why was there no Yenisei Kyrgyz Empire on the steppes? First of all, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were not a Turkic people and had completely different set of political traditions than the Turks. The Orkhon Valley had little significant value in their eyes, and establishing a Khaganate would necessitate migrating to a new, unfamiliar land. Establishing a Khaganate-style state would simply have been outside of their own political traditions.92 The more significant hindrance was that occupying the Orkhon Valley and the steppes would entail a significant, even enormous change to their lifestyle and culture, more than just political.

Like almost all pre-modern peoples, the Yenisei Kyrgyz had a way of life and economy that were in congruence with their local environment. Those who lived on the steppes or in mountains relied on pastoralism and animal husbandry, those living near the sea or rivers fished, and if the land was suitable, the people would farm. The Yenisei Kyrgyz in southern Siberia lived in a forest-steppe, mountain-meadow environment and they occupied an economic niche specialized for that type of environment. As mentioned prior, the Kyrgyz only nomadized in the summer, and agriculture constituted a larger role in their diet than it did for traditional steppe nomads. Agriculture was practiced in the Orkon Valley and elsewhere, and contrary to what is commonly assumed, nomads were rarely “fully nomadic.”93 Nevertheless, a steppe nomad’s diet was largely constituted of dairy and meat, whereas their consumption of grains and vegetables was minimal. In April, the Kyrgyz sowed millet, barley, wheat, Himalayan barley and rye, and harvested these crops in October.94 There is also archaeological evidence of extensive irrigation along the Yenisei and its tributaries. In all likelihood, even in the summer months only a portion of the population nomadized.

The Kyrgyz also maintained unique commercial relations that were determined by their local environment. They traded products from the forests of Siberia such as furs and musks, which they sold to the Turks, Arabs and Tibetans to their south. We can safely assume that hunting and trapping were important occupations amongst the Kyrgyz. According Chinese sources, the larger horses of the Kyrgyz were unsuited for steppe as they would have had a harder time foraging for grass underneath the snow during the winter.95

By all accounts, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were highly successful within the unique ecological niche they occupied. Relocating to the Mongolian Plateau would necessitate immense changes to their way of life. Realistically, the process of establishing an empire on the steppes would have resulted in their material and political culture being totally upended. Moreover and most importantly, there would be no guarantee that such a change would even be successful. It would be just as likely that another tribe would come and sweep them away, just as they had swept away the Uyghurs. The lifestyle and economy of the Yenisei Kyrgyz was probably similar in terms of general characteristic to the Russians, who also occupied the forests and forest-steppe zone situated just north of the steppes proper. It is worth noting that the Russians were only able to penetrate and colonize the steppes in the 16th century thanks to gunpowder technology from the West.

If the Kyrgyz had managed to establish a Khaganate, they would have seen no support from China. As stated before, both tribute and the silk-horse trade was critical in facilitating the power of the Uyghurs. The formation of nomadic states largely depended on the ability of a charismatic tribal leader to secure wealth from a sedentary society, and then distribute it his followers. Success in raiding and extorting wealth from a sedentary state would draw more followers to the tribal leader, creating a snowball effect that if continued could result in the creation of a grand empire such as the Uyghur’s. Unlike the Uyghurs who secured these highly favorable trade terms with the Tang as a result to their involvement with the An Lushan Rebellion, the Yenisei Kyrgyz would have been unable to recreate equivalent trade and political relations for practical reasons. Being unable to siphon a comparable amount of wealth from China that the previous Turkic Empires had done, the Kyrgyz would have found it very difficult to unify the steppe tribes around themselves.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz’s assault on Ordubaliq was more akin to a piratical raid then a conquest. And for years afterwards the Kyrgyz continued to raid across the Mongolian steppes, killing and capturing all the remaining the Uyghurs they could find. After the 840’s the Yenisei Kyrgyz largely disappear from history, simply due to their geographic remoteness from China, the region’s only significant literary culture. The Kyrgyz Khagan who destroyed Ordubaliq was himself killed by an official sometime around 847. The Yenisei Kyrgyz only reenter into historical memory during the Mongol era.

The Flight of the Uyghurs

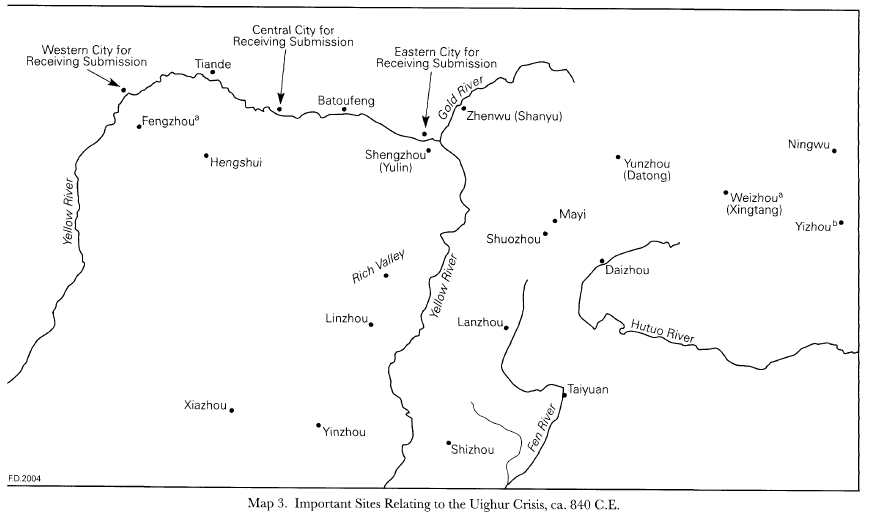

Fleeing from the Kyrgyz onslaught, the Uyghurs migrated in three main directions, towards the Tianshan Mountains, the Hexi Corridor, and to China’s Great Wall Frontier. Additionally some Uyghurs fled further west, and were absorbed by the Karluks in Semirechye, and the Kimeks in modern day northern Kazakhstan. The reason for the Uyghurs’ migration to differing destinations was likely due to longstanding tribal rivalries. This tribal factionalism will be most evident among the Uyghurs who approached the Tang frontier.

Before continuing, a short note on the sources. What is known about the Uyghur migrations following the collapse of their Khaganate is almost entirely based on Chinese sources. Much of what is known about the Uyghurs who migrated to Turfan and Gansu mainly comes from Song Dynasty sources.96 The Chinese did not pay much attention to those Uyghurs. Not only were these regions geographically removed from the Tang realm by the mid-9th century, the Tang state was itself very weak and inward looking. China of the Five Dynasties period that followed the Tang collapse in 907 was even more inwardly focused. The Song Dynasty partially reunified China in 960, but its geographic center of gravity was further south than the Tang’s and thus more distant from Uyghur affairs in Inner Asia. The Turfan Uyghurs did leave behind an enormous corpus of literature; they are largely ecclesiastical in nature, while some information on the Gansu Uyghurs is known from documents discovered at the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang.97 As will be seen, the Uyghur who approached the Chinese frontier are the best documented, in both primary and secondary sources.

The Uyghur Migration to the Turfan Depression and the Establishment of the Qocho Idiqut State

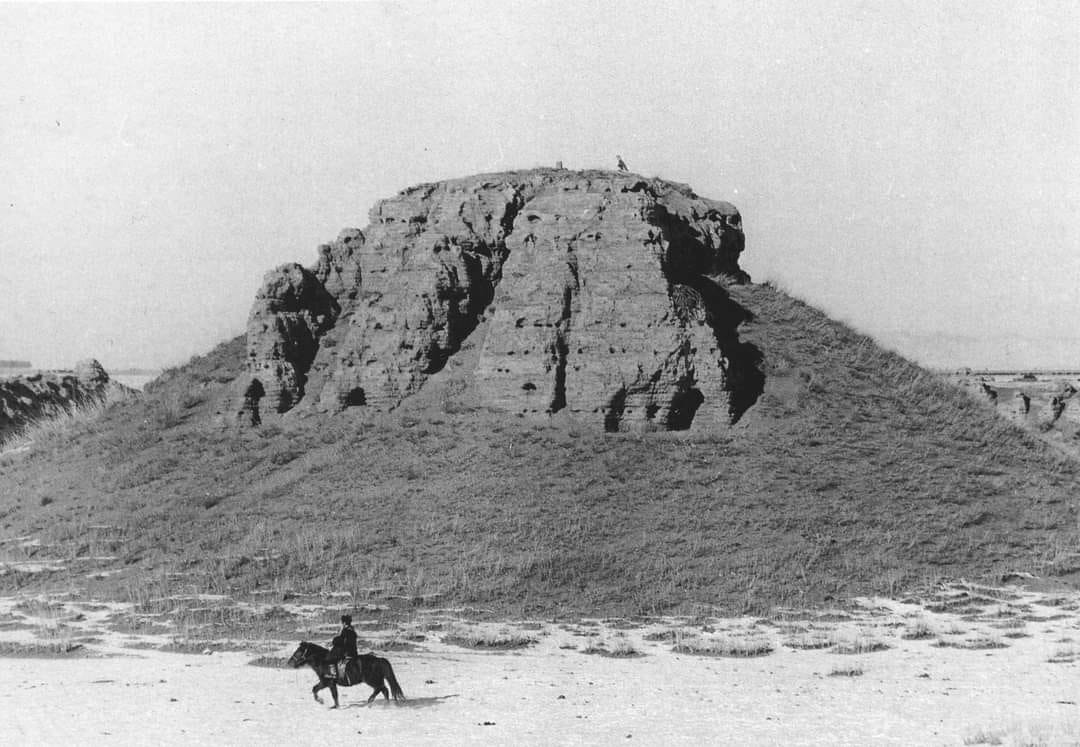

The Turfan Depression is a small lowland oasis region, located 154 meters/505 feet below sea level. It is situated between the Hexi Corridor and the larger Tarim Basin. The region was settled by the Indo-European Tocharians who likely migrated there from the Afansevio culture in south Siberia sometime around 2000BC. In fact, it is very possible the Tocharians shared the same ancestors as the Yenisei Kyrgyz. Sometime prior to the Han Dynasty’s expansion into the Tarim Basin, the Tocharian Jushi Kingdom was established in the Turfan Depression. It was centered on the now ruined city of Jiaohe, which means “city between two rivers.” Later, the Uyghurs referred to this site as Yarkhoto, which means “cliff city.”98

During the Han-Sui interregnum when China was fragmented, the Tocharians at Turfan converted to Buddhism and built a new city east of Jiaohe, called Gaochang. The city of Gaochang later became known as Qocho under the Uyghurs. According to the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang who passed though Gaochang in 630, “There are more than 100 Buddhist temples, and more than 5,000 monks and novices, and all belong to the Sarvastivadin sect of Hinayana.”99 Gaochang was one of the most important trade emporiums along the Silk Road, as most caravan trade routes running westwards from China would transit through the Turfan Depression before branching into different directions.

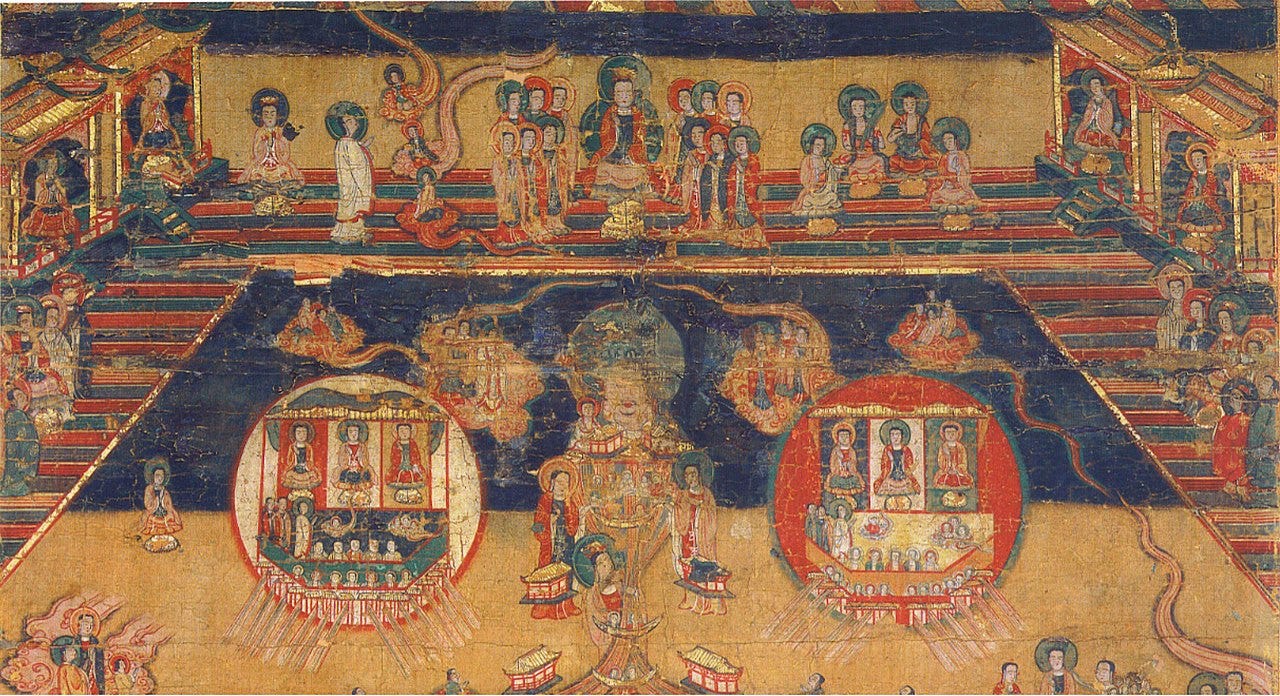

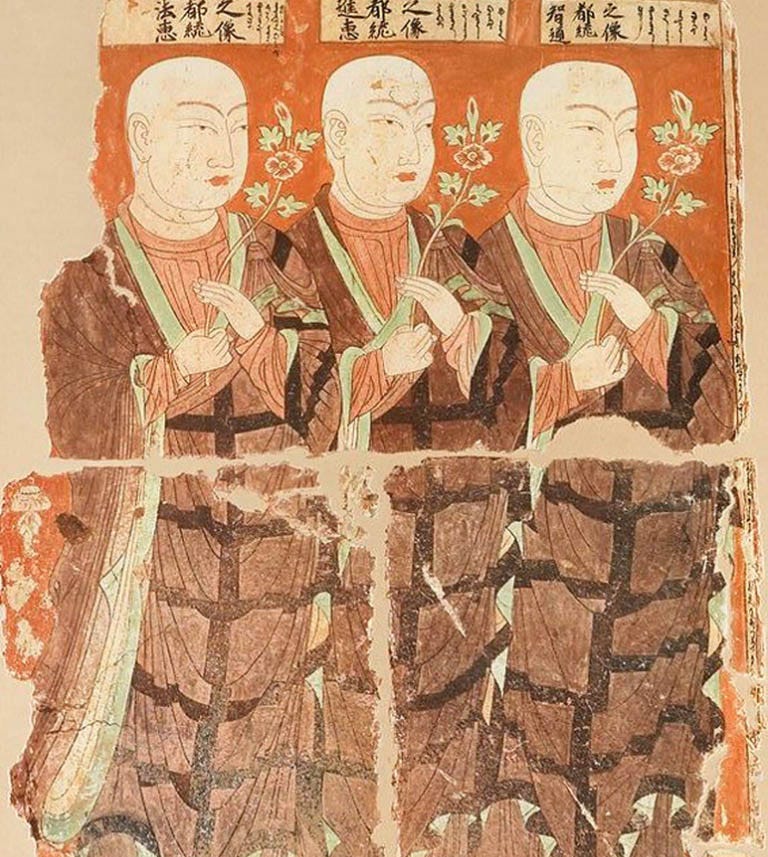

When the Tang Dynasty expanded westwards in the 7th century, Gaochang was renamed Xizhou and became one of the Tang’s main garrisons in the Anxi Protectorate.100 According to Tang census records, in 640 the Gaochang kingdom had 8046 households, containing 37,738 people in 22 cities.101 Gaochang’s demographics would have been very mixed. Along with Tocharians, there also would have been Sogdian and Chinese settlers. There was also likely a Turkic presence around Beiting prior to Uyghur migration and likely some Turks in Gaochang as well. While Buddhism was the dominate religion, there were also Nestorian Christians and Zoroastrians, and even a small Jewish presence. The multicultural milieu of the Turfan Depression can be seen in the varied physiognomies depicted in the murals at the Bezekilk Thousand Buddha Caves that were built during the Uyghur period.

North of the Turfan Depression, on the far side of the Tianshan Mountains is Zungaria, an arid steppe region. During the Tang period, Zungaria was known as the Beiting Protectorate, with its headquarters at Beiting city, whose ruins can be found in Jimsar County, immediately east of modern Urumqi, the provincial capital of Xinjiang. Zungaria and the Turfan Depression are connected by the Dabancheng Pass, a large defile that effectively splits the Tianshan Mountains into two sections. Dabancheng Pass allows for very quick travel between the steppes of Zungaria and the Turfan Depression, from where roads further east to Hami and Dunhuang, or west to Karashahr and Kucha.

Sometime after the destruction of Ordubaliq, 15 tribes of Uyghur and Toquzoguz Turks were lead to the Tianshan Mountains by the Uyghur aristocrat Manglig Tegin and a minister named Sa-chih.102 These Uyghurs were not lead by the royal Yaghlaqars, but instead by the Ediz tribe. Due to a general lack of sources, the movements of these Uyghurs and the exact timeline of the founding the future Qocho Idiqut state are difficult to determine. What is known is that the Uyghurs under Manglig Tegin did not immediately go to Beiting and Xizhou, but instead moved towards Karashahr and Kucha in the Tarim Basin, then under Tibetan control.103 The Uyghurs wrestled control of Kucha from the Tibetans, whose rule was already very tenuous by this time.104 Their animals were likely grazed in the nearby grasslands of the Yulduz Basin and the Bayingolin grasslands. At Karashahr and Kucha the Uyghurs attempted to make contact with Tang and request formal recognition, but their envoy was killed enroute and never made it to Chang’an.

The Tibetan Empire began to unravel in 848 due to Zhang Yichao’s rebellion in Dunhuang. Zhang had been some sort of Chinese military commander under the Tibetans, and after his successful rebellion he became the ruler of the “Guiyijun,” or in English, “Return to Righteousness Army.”105 Soon after throwing off Tibetan rule in Dunhuang, Zhang declared allegiance to the Tang Dynasty and ejected the remaining Tibetans from the Hexi Corridor and Turfan Basin. While the timeline of the Guiyijun is known, the dates of Menglig Tegin’s migrations are not. The Uyghurs probably entered the Kucha region after 848, but this is not certain. Either way, whoever struck first against the Tibetans gave unintentional assistance to the other.

Sometime in the 850’s, Mengling Tegin’s Uyghurs moved towards Xizhou and Beiting. According some sources the Uyghurs expelled the Tibetans from the two cities, while other sources say they captured these cities from the Guiyijun. Either way, by 857 the Uyghurs had gained control of the former Beiting Protectorate and Beiting city. Additionally, it appears there were several waves of Uyghur refugee who arrived to Zungaria. Possibly the capture of Beiting was spearheaded by Uyghurs who arrived later and not those who initially migrated with Mengling Tegin, but this is uncertain. Possibly, these later arrivals were Turks who had lived south of the Altai Mountain under the former Khaganate, and then migrated south to Beiting in conjunction with Uyghurs invading from Karashahr. If this is true, then these tribes were not Uyghurs or Toquzoguz but became known as Uyghurs under the Qocho Idiqut.

Under the Uyghurs, Beiting was renamed to Beshbaliq, which means “five cities.” In 866 the Uyghurs then gained control over Xizhou and the Turfan Depression on the opposite side of the Tianshan Mountains.106 Uyghur ruler over Xizhou was recognized by the Tang court in the same year. With the capture of the Turfan Depression, the Uyghur leader Pugu Jun declared himself the “Idiqut”, which means “auspicious qut.”107 A year later in 867, the Uyghurs seized control of Yizhou, modern Hami, from the Guiyijun.108

The Uyghur Qocho Idiqut State

The Uyghur state in Qocho represents a second, and much longer, incarnation of Uyghur statehood that survived for over 400 years. The Qocho Idiqut state stretched from Hami in the east to Kucha in the west, and as far as the southern slopes of the Altai Mountains in the north and southwards to the Altyn-Dag Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The city of Qocho, which is located about 40 kilometers east of modern Turfan, became the Uyghurs’ winter capital. Qocho was also known as “Idiqut Sahri,” which means “City of the Idiqut.”109 Beshbaliq and its environs served as their summer capital, which allowed the Uyghurs to escape the Turfan Depression’s summertime temperatures that can rise to 50 Celsius/122 Fahrenheit, making life quite unpleasant. Moreover, the land north of the Tianshan Mountains was steppe, allowing the Qocho Uyghurs to nomadize as they had done traditionally.110 The ruins of the old Beiting/Beshbaliq have been uncovered in modern Jimsar County, about 150 kilometers east of Urumqi.

The Uyghurs at Qocho called themselves the Arslan Uyghurs, or “Lion Uyghurs” in English, likely in order to differentiate themselves from the other Uyghurs who migrated elsewhere. As mentioned above, the ruling title was no longer Khagan but Idiqut. This term likely came from the Basmils, the same tribal grouping that had rebelled against the Second Turkic Khaganate alongside the Uyghurs in the 740’s. After being defeated by the Uyghurs, the Basmils migrated to Zungaria, nomadizing in the vicinity of Beiting/Beshbaliq.111 It is very likely the Basmils were incorporated into the Uyghur/Toquzoguz tribal grouping that went to Qocho, with the tribal elites fusing together.