The Mysteries of the Chinese Palace in South Siberia

Uncovering the ancient Chinese palace on the Yenisei River and examining the Xiongnu Empire in Siberia

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

“While soldiers at the northern border vainly look toward home. The fury of the wind cuts our men's advance In a place of death and blue void, with nothingness ahead. Three times a day a cloud of slaughter rises over the camp; And all night long the hour-drums shake their chilly booming, Until white swords can be seen again, spattered with red blood. ...When death becomes a duty, who stops to think of fame? Yet in speaking of the rigours of warfare on the desert We name to this day Li, the great General, who lived long ago.” – Gao Shi, A Song of Yan Country, 300 Tang Poems

Introduction

The great expanse of Siberia has long remained shrouded in mystery, not just to us today, but also for the peoples that lived distant from it to the south. The Greeks looking north spoke of Siberia as being the realm of the Hyperboreans, whose homeland lay behind the Riphean Mountains, from where the northerly Boreas wind blew from and from where the rivers of Scythia had their origins. The lands approaching the mountains were said to be completely covered in darkness and home to the Arimaspi, a tribe of one-eyed Scythians, while beyond the mountains was Hyperborea, the “Land of the Blessed” where the sun never set and whose inhabitants lived in complete abundance. Apollo wintered there, flying from Hellas in a chariot pulled by swans. The only mortal to have stepped foot in the depths of Hyperborean Siberia was Aristeas, who is mentioned only apocryphally by Herodotus and a few other sources.1

In later centuries the Christians would adopt the eschatological prophecies of Gog and Magog from the Alexandrian Jews, who believed that the end of the world would be marked by the coming of the botched descendants of Japheth from far north. The Christians of Byzantium and Syria mixed these ideas with legends surrounding the life of Alexander the Great, and came to believe that Alexander had built a gate somewhere in a mountain pass that sealed Gog and Magog off from the civilized world. But eventually they would break through the gate and come down from the far north, initiating the final battle near Jerusalem and the Second Coming of the Christ.2

What little was known about Siberia was recorded primary by Chinese and Muslim writers who were located more than a 1000 miles away to the south and often only recorded the scantiest of details. Han Chinese sources only briefly mention the Dingling, Jiankun and Xiajiasi peoples who lived beyond Sayan Mountains, and the Muslims in Central Asia only vaguely understood where the furs they were purchasing came from. Only the Tang Dynasty in the 9th century came into direct and sustained contact with Xiajiasi, known in English as the Yenisei Kyrgyz, and this only became possible with the elimination of any intervening nomadic power on the steppes. Upon seeing the Xiajiasi, the Chinese recorded them as being tall, with red hair and green eyes. Seemingly, the Hyperboreans had crossed the Riphean Mountains to visit China.

While a mystery to the outside world who were separated from Siberia by steppe nomads, great distances, and even greater severity of climate, Siberia played an integral role in Eurasian history. In the 2nd millennium BC, Indo-European Aryans migrating eastwards from the southern Urals region formed what would later becoming known as the Andronovo culture that encompassed the Kazakh steppes and southern Siberia up to the Altai-Sayan Mountain region. The descendants of the Andronovo culture would become the earliest Scythians, whose graves dating from the 9th to 3rd centuries BC have been found at Arzhan in Tuva and at Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains. Other descendants would migrate south into the Tarim Basin and up to the frontiers of China, becoming known as the Tocharians and the Yuezhi, the latter of whom would later destroy Greek Bactria in the 2nd century BC.

The entirety of the “Silk Roads” intersected with “Fur Roads.” Every nomadic state on the steppes sought to extend its power northwards into Siberia with the aim of securing its fur resources, which were then exported to markets in the south, namely China, Tibet, Central Asia and Persia. The most prominent example of an empire on the “fur roads” was the Kimek Khaganate of the 8th and 9th centuries, whose capital was located near modern day Pavlodar on the Irtysh River which flows north to the Kara Sea and whose drainage basin covers all of western Siberia. Located just south of where the steppes meet the southern forests of Siberia, the Kimeks controlled the trade routes that brought the furs of Siberia to markets in the south in Central Asia and Persia. Centuries later when Russia expanded across Siberia beginning in the late 16th century, their goal was simply to monopolize the fur trade for themselves, and soon they were exporting the furs of Siberia across Eurasia, to Europe, Persia and China. Only with the French and English expansion into Canada and their creation of a global maritime system of trade, was this monopoly broken.

The expansion of Russian across Siberia finally brought its mysteries to light, but even then, they were often only understood centuries later. Following the Petrine reforms of the early 18th century, scientific learning was introduced to Russia. This was soon followed by Germans and other Westerners who helped modernize Russia, a process which entailed the “rediscovery” of Russia’s territories in light of the new Western approaches to the statecraft and to scientific methods. German explorers and researchers of Siberia such as Gerhard Friedrich Miller and Johann Eberhard Fischer who helped “rediscover” Siberia were soon followed by Russians themselves, such as Grigory Ivanovich Spassky and Vasiliy Vasilevich Radlov, who uncovered ancient Scythian mines in Altai and Turkic fortresses in the Sayan Mountains.

Yet, one of the most fascinating and enigmatic discoveries of Siberia’s ancient past was only made in the Soviet period, on the eve of the German invasion, in the Minusinsk Basin in south Siberia. There, a palace was discovered whose floor space covered more than 1500 meters².3 Even more fantastic, the palace appeared at first to have been Chinese in origin. The archaeologists quickly connected the palace they had discovered to the story of Li Ling, a Han Dynasty general who was reportedly exiled to the Dingling people, later known as the Yenisei Kyrgyz, during the 1st century BC. As it would turn out, the actual origins and history behind this “Chinese palace” are much more complex than initially thought.

The Discovery of the Tasheba Palace

The ruins of the palace were first discovered in 1940 by a construction team while they were building a road between Abakan, the capital of Khakassia, and the collective farm named “Sila” (later renamed to Chapaevo), located 15 km southwest of Abakan. While laying out the road, the workers cut into the southeastern corner of a small hill that stood only 2 m tall made of alluvial slit that was located 500 meters from the Tasheba River, which gave the site its name.4 To their surprise, the team cut straight through the ruins of an adobe wall 2 m thick.5 Realizing they had stumbled among a significant discovery, archaeologists were called.

The only trained archaeologist available was Varvara Pavlovna Levasheva of the Minusinsk Museum in Krasnoyarsk Krai who was called back from leave in Crimea, and whose background deserves a brief retelling. In the 1930’s both Levasheva and her husband F. P. Kravchenko were archaeologists at the Minusinsk Museum, but during the Great Terror of 1937 Kravchenko was arrested and shot by the NKVD. Widowed with two young children, Lavesheva developed a stutter and pulmonary tuberculosis due to a nervous shock, and soon went to Crimea to recover. With the discovery of the palace in 1940 she returned to the Minusinsk Museum upon their request to work on the excavation.6

Work on excavating the palace only began in the early summer of 1941. Realizing the full scope of the project, in early June of 1941 Levasheva called upon additional archeological specialists to help her lead the excavations. Linda Alekseevna Evtyukhova and her husband Sergei Vladimirovich Kiselev were both sent by the State Historical Museum in Moscow to Khakassia.7 While excavations were already underway, they were soon halted due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union which began on 22nd June, 1941. Evtyukhova and Kiselev themselves only arrived to the site a few days after the war began.8 Work only resumed in the summer of 1945, headed by Evtyukhova and Levasheva.9 The excavation was only completed in 1946. Unfortunately, the entire southeastern corner of the palace was unknowingly destroyed by the road building team as they cut through the hill. Nevertheless, the rest of the palace’s walls remained in good condition, but stood no more than 2 m above the ground.

What initially led Evtyukhova and Levasheva to believe this was a Chinese palace were the numerous roof tiles found around the palace that had inscriptions of Chinese characters. These inscriptions were later translated by the Soviet Sinologist Vasily Mikhailovich Alekseev, who dated them to the 2nd or 1st centuries BC.10 Evtyukhova and Levasheva then quickly connected this “Chinese palace” to the story of Li Ling, a general of China’s Han Dynasty that was captured by the Xiongnu, the nomadic empire who ruled the steppes north of China at the time, and was subsequently exiled to the Yenisei River and served as the Xiongnu’s local viceroy in the region. The Han court labeled Li a traitor and Emperor Wu ordered his family executed. Denied by his homeland, denounced as a traitor, and forbidden to return, Li Ling reportedly spent the remainder of his life in Siberia on the banks of the Yenisei.

While the theory that the palace found near the Tasheba River belonged to Li Ling is fully possibly, the story itself lacks any hard evidence. The theory relies entirely on Chinese chronicles, whose stories of Li Ling could very well have been embellishments or legendary tales attached to the real historical figure of Li Ling. Later researchers came to different conclusions regarding who the palace belonged to. The two other competing theories argue that the palace was the residence of either Lu Fan, the false emperor who attempted the raise a rebellion against Wang Mang and his Xin interregnum regime and subsequently fled to the Xiongnu, or Yimo, the daughter of the Chinese princess Wang Zhaojun who married the Xiongnu ruler Shanyu Huhanye.

While the Li Ling theory is disputable, the claim by Evtyukhova and Levasheva that the palace was “built by Chinese for Chinese” has come under far greater doubt.11 As will be seen, later researchers have concluded that the palace and its construction methods are of Central Asian origin far more so than Chinese. In fact, the Chinese characters on the roof tiles proved to be the only aspect of the building that linked it to China in any meaningful way.

But before examining the palace ruins and the theories surrounding it, let us first turn to the historical context in which it was constructed.

The Empire of the Xiongnu and its Relations with China

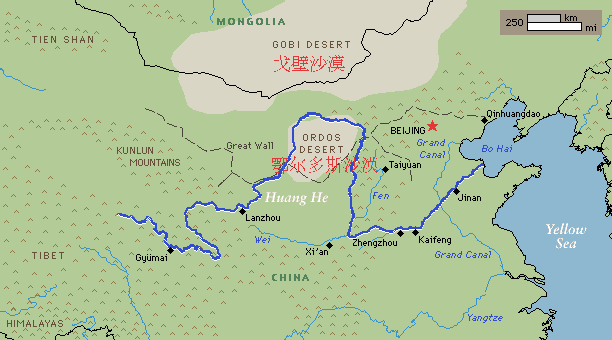

The Xiongnu were a nomadic people, originally based in the Ordos plateau, an arid steppe region of loess soil that is enclosed by the great bend of the Yellow River and is today located in northern Shaanxi province as well as part of Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Gansu and Ningxia. The Xiongnu first entered into history shortly after the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, unified China in 221 BC. Following the Warring States period Qin Shi Huang began to consolidate and expand China’s defenses along its northern frontier, which culminating in the creation of China’s first Great Wall system. In the process, the Xiongnu were attacked and pushed out of the Ordos region northwards into the Gobi desert. For a while they disappeared, lost in the steppes beyond the Great Wall. In the south, China’s the first empire the Qin Dynasty ruled “all under Heaven” in peace, but following the death of the first emperor in 210 BC that peace quickly fell apart and the Qin Empire collapsed in 207 BC.

Meanwhile on the steppes, the defeated and lost Xiongnu soon came under the rule of the Shanyu (emperor) Modu, a ruthless and charismatic leader who successfully united the tribes.12 The state was organized into what Thomas Barfield describes as an “imperial confederacy”, which was “autocratic... in foreign and military affairs but consultative and federally structured for dealing with internal problems.”13 In other words the Shanyu, while nominally an emperor, in fact had limited authority within the Xiongnu state itself due to the nomadic and highly mobile nature of his subjects. If he ruled badly or tyrannically, his subjects could easily migrate away and flee from his rule. Nevertheless, the Shanyu sought to monopolize control over foreign relations, and specifically relations with China. This meant that all tribute from China would be disturbed at his digression, thus forcing subordinate tribes to be subject to him personally if they wanted access to the flow of goods being extracted from China.

Soon after unifying the tribes, the Shanyu Modu led the Xiongnu in a series of campaigns and conquered all the peoples on all four directions. They attacked and subordinated the Donghu in Manchuria to the east, the Dingling people in Siberia to the north, the Yuezhi in the Gansu corridor and Tocharian states in the Tarim Basin to the west and in the south they reignited their conflict with China.14

The Chinese empire was also quickly reunified by Liu Bang, a former prison guard who became leader of the convicts he was tasked with guarding. He founded the Han Dynasty in 202 BC as the Emperor Gaozu. The Han sought to be the sole Chinese state and to “rule all under Heaven” as the Qin had done, and thus aimed to control the same territorial space as its predecessor. Thus, the revitalized Xiongnu and Chinese empire some came into conflict for the border lands between them.

The Han-Xiongnu began in 201-200BC, when the Xiongnu attacked a Han aligned state on the northern frontier who quickly defected from the Han and aligned itself with the Xiongnu on the steppes. This prompted the Emperor Gaozu to mobilize an army and march north to punish the Xiongnu. There, the Han army was lured by a feint-retreat maneuver and were then trapped by Xiongnu cavalry at the Ping Cheng fortress, near modern day Datong city in Shanxi province. Surrounded with no chance of escape, the Emperor Gaozu made a deal where he and his army would be released, and in exchange for huge volumes of tribute were to be given to the Xiongnu in form of food, silk, wine and other goods. A Chinese imperial princess would also be married the Shanyu. Lastly, the states were to engage in further relations as equals, something which greatly humiliated the Han, who viewed itself as being the universal state, unrivaled in its rule.15 This “Xiongnu problem” as seen by the Han court continued until the policy was suddenly changed in 133 BC by the Emperor Wu.16 The Han court had determined that the empire was now sufficiently strong enough to challenge the Xiongnu, and set about finding allies who could help the Han in their upcoming struggle.17

The envoy Zhang Qian was dispatched to make contact with the Yuezhi in 138 BC, and while unsuccessful in his primary task, he did return with a great deal of intelligence on the “Western Lands”, the lands of Inner and Central Asia that lay beyond the western frontiers of China. As it turned out, the Xiongnu were highly dependent on trade with the city-states of the Tarim Basin. The Han court determined that a prudent course of action to take for the goal of defeating the Xiongnu would be to “cut off their right arm”, or in other words break the Shanyu’s hold over the Tarim Basin and serve their trade ties with the rest of Eurasia. In 121 BC the Han conquered the Hexi Corridor that leads from China proper to the Tarim Basin, and in 104 BC the Han Dynasty invaded the Tarim Basin and began subduing the Tarim states.18

The war with the Xiongnu dragged for decades. Xiongnu cavalry regularly raided the Hexi Corridor and the Tarim Basin, and attempted to force the Tarim states to break off their relationship with the Han Dynasty. It was during one of these raids that the Han general Li Ling, who Evtyukhova and Levasheva thought to have resided in the Tasheba palace, was captured.

In 99 BC Li Ling commanded a force of 5000 cavalry near the oasis of Etsin-Gol in the Gobi desert, a strategic midway point between the northern steppes and the Hexi Corridor that was necessary to hold in order to protect the Han’s supply lines between China and Central Asia. While reacting to a Xiongnu force Li Ling was lured north into a mountain gorge and was trapped, and forced to surrender.19 Sometime shortly after Li presumably renounced the Han Dynasty and submitted to the Shanyu Qiedi of the Xiongnu. According to Chinese chronicles, in 98 BC he was given the Shanyu’s daughter to marry and sent to the Yenisei River in Siberia to be the local viceroy who would rule on behalf of the Shanyu.20 He was reportedly provided with a garrison of Xiongnu soldiers and was accompanied by some of his Chinese soldiers who were also captured alongside him.21

Years later Li Ling went to the shores of Lake Baikal to visit his old friend Su Wu, a Han envoy to the Xiongnu who had been arrested in 100 BC due to members of the party engaging in espionage. As punishment, Su was exiled to Baikal and forced to herd sheep.22 In 81 BC Su was given permission to return back to China, and he attempted to convince Li to return with him, and said that the emperor would likely show mercy. But Li rejected this saying, “my family has been captured and exterminated, this the greatest disgrace, and for me there is nothing more to hope for. It is all over. All that I want is you to know is what is in my heart. A person of another country, we will part forever”. With this Li began to dance and sang a song bidding Su Wu farewell:

“I went 10,000 li across the desert And as the emperor’s military commander I fought decisively against the Xiongnu. Along the way I found myself in a hopeless position. Arrows were fired, swords were broken. The warriors all died, And together with them by glory. My elderly mother is already dead. And although I wish I could thank the emperor for his mercy, How can I return back?” (Кызласов, 139.)

Similar to the Princess Xijun who was sent off to marry the king of the Wusun in 105 BC, Li Ling and Wu Su would remain favored figures in Chinese literature throughout the centuries, as heroes yearning to return home but doomed to live out their days in exile among barbarians in the far north. And while Xijun and Su Wu eventually returned to China, Li Ling remained on the shores of the Yenisei until his death in 75 BC.23

South Siberia during the 1st Century BC

The arrival of the Xiongnu and Li Ling to south Siberia dramatically altered life in the Minusinsk Basin, both at a cultural as well as biologically level. At the beginning of the 2nd century BC the people of the Minusinsk Basin were a part of what archeologists have named the Tagar culture. The arrival of the Xiongnu to the Minusinsk Basin coincided with the transition period between the older Tagar culture and the Tashtyk culture, a process which likely was in part triggered by the transformative effects that the Xiongnu had on the local culture and economy of the region.24 During this period irrigation, brick architecture, and pig breeding were introduced to the region, likely from China via the Xiongnu.25 During this period tombs in Minusinsk Basin became much larger and began containing a far greater quantity of valuable goods. This is almost certainly a consequence of the region’s integration with Silk Road commercial networks due to its inclusion to the Xiongnu empire.26

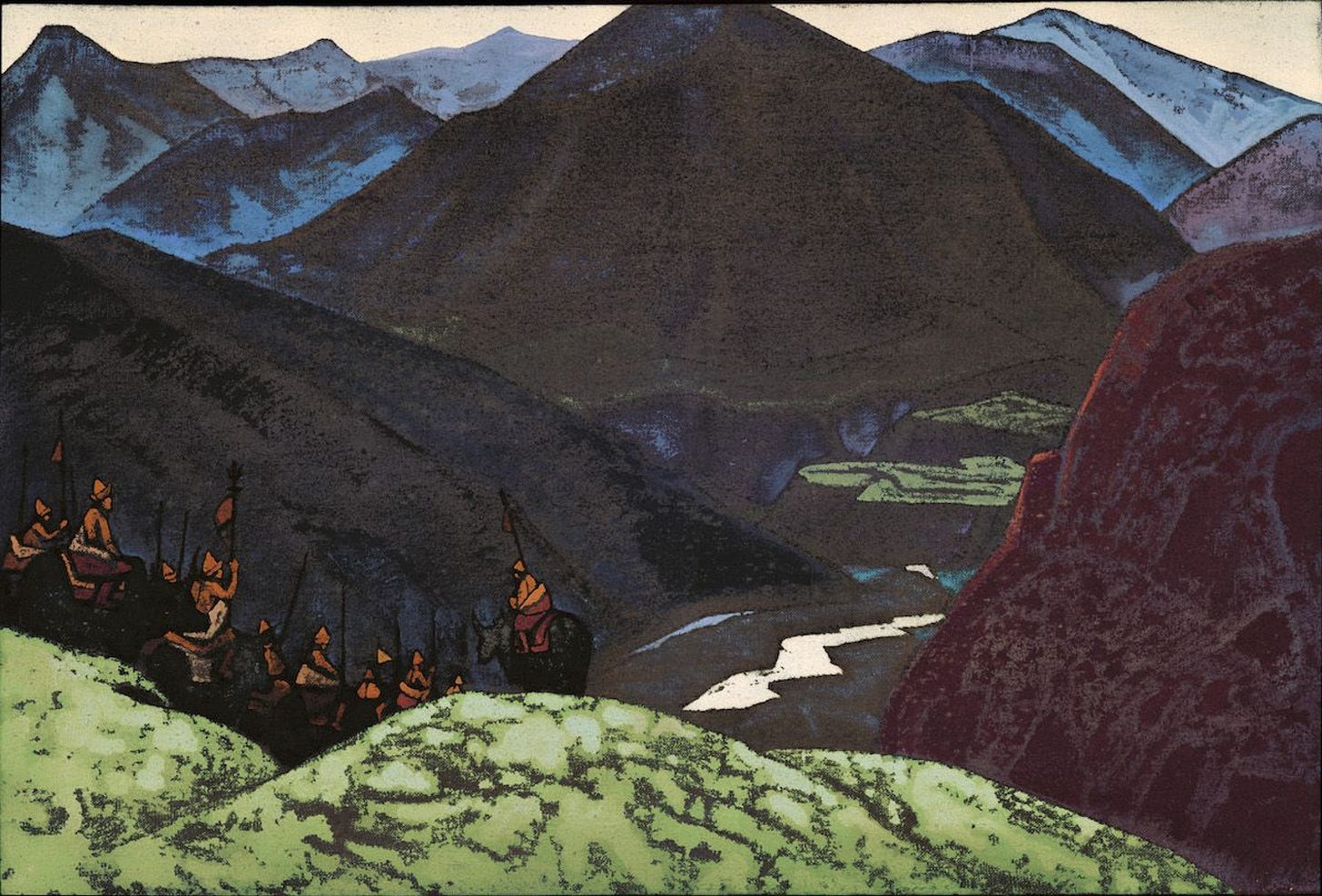

The Minusinsk Basin is located just north of the Mongolian plateau, beyond the Sayan Mountains which form an eastwards extension of the Altai Mountains. Repeatedly throughout history the great nomadic empires of the steppe rode north to the Ubsunor Basin. From there, they would continue north, crossing the Tannu-Ola Mountains to the headwaters of the mighty Yenisei River in modern day Tuva, and then follow that river as its flows northwards through the Sayan Mountains into the Minusinsk Basin. Later during the Uyghur epoch of the 8th and 9th centuries the people of Minusinsk, known as the Yenisei Kyrgyz, were vastly more powerful, and the Uyghurs were forced to construct a series of fortresses across Tuva in order to protect the northern flank of their empire. But during the Xiongnu era it was completely different. The people of the Minusinsk Basin, known to the Han Dynasty as the “Dingling” people were vastly less sophisticated than the later Yenisei Kyrgyz and were unable to prevent their conquest by the Xiongnu.

The Xiongnu under Modu Shanyu attacked the Dingling around 201BC and made them vassals of the empire. This was likely done for several reasons. First, the Xiongnu likely wanted the furs of Siberia, which could sold to the Chinese and to others in the south for great profit. Additionally, the Minusinsk Basin processed rich metal deposits and arable land. The Xiongnu certainly would have wanted both, as the metal was necessary for weapons and armour, while grain would have represented a useful supplement to the nomads’ diet of meat and dairy.

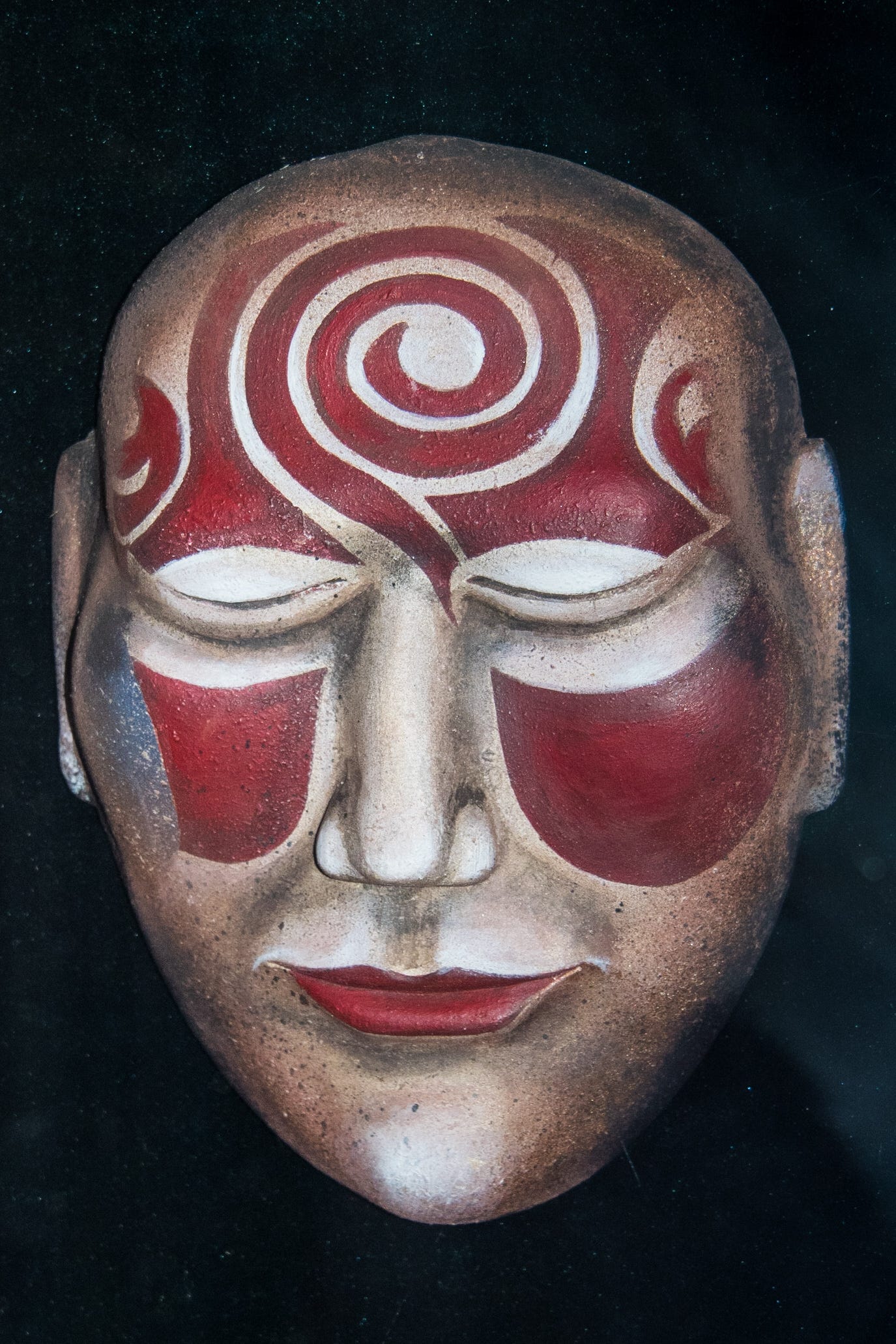

It is also known that the coming of the Xiongnu to south Siberia brought with it significant demographic changes to the region. Prior, the people of the Tagar culture were likely entirely Caucasian in appearance. But during the Tagar-Tashtyk transition period from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD Asian features began appearing among the local people. Levasheva and Evtyukhova argue that the faces of the Tashtyk funeral masks are indicative of this change in physiognomies, although what race these masks depict is not a settled matter.27 Nevertheless, the Yenisei Kyrgyz remained largely Caucasian in appearance. Tang Chinese sources noted that those with Asian features were in the minority, and the 11th century Persian writer Gardizi noted that Yenisei Kyrgyz, ancestors of the Tagar-Tashtyk cultures, had "reddishness of hair and whiteness of skin” and believed them to be related to the Slavs.28

Yenisei Kyrgyz themselves understood that it was during the Xiongnu epoch that Asian features began appearing among them. According to the Kyrgyz, the source of these Asian features, such as dark hair and dark eyes, was the General Li Ling and his Chinese garrison who mixed with the local population. Centuries later in the 9th century after the Yenisei Kyrgyz had smashed the Uyghur Khaganate in a bolt from the blue lighting strike and finally established uninterrupted diplomatic contact with Tang China, Tang writers noted the Kyrgyz as being largely Caucasian in appearance, with red hair and either blue or green eyes, with some having typically Asian features. While having Asian features were deemed to be unlucky by the Yenisei Kyrgyz, they nevertheless proudly presented themselves as the ancestors of the legendary Han General Li Ling to the Tang court.29 Their reputed ancestry was all the more important as it linked them to the royal family of the Tang Dynasty, the Li family, who themselves were distantly related to Li Ling.30 This provided the Kyrgyz envoys with greater prestige and rank at the Tang court when they visited. The Emperor Zhongzong even said: "Your nation and ours are of the same family; you cannot be compared with other foreigners."31

Nevertheless, the story of Li Ling as being the source of Asian blood among the people of the Minusinsk Basin should not be viewed uncritically. Leonid Romanovich Kyzlasov argues that the people known to the Chinese as the “Jiankun” were relocated from the southern Altai-Sayan region into the Minusinsk Basin, and this was cause of the influx of Asian blood to the region.32

The Palace Ruins

As stated above, the Tasheba palace was initially described as being “built by Chinese for Chinese.” This was said not only because of the roof disks with Chinese characters, but also the palace’s architectural features which were initially thought to resemble contemporary Han Chinese architecture.33 While superficially the palace does indeed match up with many Chinese architectural norms, several glaring incongruities remain, in addition to several other features of the palace which are not Chinese in character or origin.

The palace ruins covered a space of 1500 m2. Its walls stretch 35 m from north to south and 45 m east to west.34 It had only one entrance facing south towards the sun, a typical feature among Chinese architecture. Conversely, the external walls around the palace had its entrance gate facing north, which differs from Chinese architectural norms where the building entrance and the estate’s gate both face south.35 Nevertheless, the building was oriented towards the four cardinal directions in the standard Chinese style. It is worth noting that all of the cultures in proximity to China adopted this customs of constructing buildings oriented towards the compass points. Similar buildings can be found in Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Tibet, where not only temples and palaces were built in such a way, but burial tombs as well.

It also should be noted that different recreations of the palace exist and researchers are undecided on what exactly the building looked like precisely. This primarily due to the roof, but also the general scarcity of the palace’s remains.

The Kurgan Burials and Dating

Archeologists determined with a high degree of accuracy that the Tasheba palace was built sometime around Tagar-Tashtyk transitional period, sometime between 100 BC and 50 BC.36 This is due to several graves that were discovered within the hill that covered the palace. It is believed that the palace was fully destroyed by flooding from the Tasheba and Abakan rivers.37 Alluvial silt covered the ruins of the palace, creating a small hill 50-60 m diameter.38 The hill was located 500 m from the Tasheba River, which is known to occasionally flood.39

While excavating the palace, Levasheva and Evtyukhova quickly discovered several buried bodies, some of which were buried in crevasses carved out of the walls of the former palace.40 In total, five burials were found from the early Tashtyk period. Due to these graves, Kyzlasov, Levasheva and Evtyukhova all concluded that the palace could not have existed later than the mid-1st century BC.41 In other words, not only was the palace built sometime prior to 50 BC, it was also destroyed before that time as well.

In fact, the entire hill contained several distinct cultural layers, dating from the Tagar-Tashtyk transition period up to at least the 17th century. While digging, archeologists initially encountered fire pits 40-50cm deep all over the hill which contained animal remains. Additionally, a ritual birch tree was discovered buried in the middle of the hill.42 Kyzlasov believed the hill was used for Manichean and Tengrist ceremonies during 8th and 9th centuries, but this is doubtful.43 Manichaeism was the state religion of the Uyghur Khaganate, the arch enemy of the Yenisei Kyrgyz and it makes little sense that they would adopt the religion of their rival. Further burial sites were found all over the hill, including a women buried in a hollowed out poplar log, which was a common burial custom in the Sayano-Altai region from the 13th to the 14th centuries during the Mongolian epoch.44

The hill was constantly used as a burial grounds and as a religious site throughout the ages. Its height likely made it an attractive spot for local people to host their ceremonies and served as a kurgan of sorts.

Later Chinese researchers and Russian sinologist confirmed the dating of the palace to the 1st century BC. As mentioned above, the Soviet Sinologist V.M. Alekseev translated the roof disks with Chinese inscriptions, and confirmed their dating to the Han Dynasty.45 Chinese researchers also agreed with the dating, but believed the palace was not built by Chinese, but by Dingling craftsmen local to the region.46 As it will be seen, these Chinese researchers were mostly correctly in their assessment, although with some qualifications.

The Palace Walls

The palace walls were 2 m thick, made of adobe compressed clay and were very strong.47 Reportedly the walls could barely be broken through with a pick and crowbar.48 No windows were found, and presumably if they existed they were located higher up on the walls and were destroyed overtime.49 The palace had no underground foundations.

According to Kyzaslov, these walls were certainly not built by the Chinese workers, but instead by craftsman brought in from Central Asia. Chinese at the time did not build using such compressed clay techniques. Instead, Chinese only built rammed earth walls.50 The construction method used to construct the palace is known as pakhsa (“пахса”), which Kyzlasov describes by quoting V. L. Voronina as being “broken clay, laid down in layers… which does not require any kind of casing or framework. In the ancient construction techniques of Middle Asia pakhsa was packed down in thick layers.”51 Kyzlasov notes that similar construction techniques that were found at the Tasheba palace were also found at Panjikent, a major Sogdian city that existed on the Zerafshan River on the territory of modern day Tajikistan, which was destroyed during the Islamic invasions of Central Asia during 8th century.52

The second, external wall that enclosed the palace estate was even more ruined that the palace’s walls. At the north facing gate the outlines of towers were found. Levasheva and Evtyukhova describe this wall around the estate as being a fence, and that it remained unfinished.53 Wooden towers likely stood at the corners of this wall.54 The size of the entire palace estate was 175m x 145 m, or 25375m2.55

Despite the construction method being different, the central walls do share the similarity with Han buildings of being thicker than the outer walls, in order to support the weight of the roof, and specifically the heavy tiles.56

The Pillars

The ceiling was held up by wooden support pillars, dug 60-80cm into the ground and rested on sandstone slabs. Some debate exists regarding whether this design is of Chinese or Central Asian origin. Levasheva and Evtyukhova argue that similar pillar designs can be found at Shang Dynasty palaces at Anyang that date to the 12th century BC.57 Conversely, S. A. Komissarov and O. A. Mitko, citing L. R. Kyzlasov, argued that the design of the pillars clearly originated from Central or Western Asia.58

The Roof and Chinese Inscription

The roof of the Tasheba palace consisted of concave tiles and semi-cylindrical gutters with disks at their ends.59 It was in the remains of the roof where the clearest evidence could be found that the palace had some sort of Chinese connection. These were the disks that were located at the end of the gutters, which were stamped with Chinese characters. The inscription on these disks said “To the Son of Heaven a thousand years of peace. (And to this we wish you) a thousand autumns of joy without grief.”60 Similar disks were found at other sites in China from the Han Dynasty, in addition to sites in the Trans-Baikal region that were dated to the Yuan Dynasty.61

More than 400 of these disks with Chinese inscriptions were found.62 Each disk was 20 cm in diameter.63 Levasheva and Evtyukhova believed that these disks were created by Chinese craftsmen who were located on site. They additionally noted that they were of excellent quality and numerous examples of them survived intact.64 Other researchers believed these disks were instead made by non-Chinese craftsman who happened to have familiarity with Chinese writing, which is entirely possible. This question exists in relation to the larger question of who this palace was built for, which is addressed further below.

While the disks were clearly connected the China, the structure of the roof itself was not Chinese in style. Unlike Han buildings of the era, the Tasheba palace did not have "flying" roof with raised corners, and instead it rested on the frame.65

Moreover, what exactly the roof looked like is also debated. Researchers had trouble determining whether the roof was single or two-tiered. The roof’s tiles were mostly found in the central chamber of the building and also around the external perimeter. This led researchers to believe the roof to two-tiered, with the tiles from the upper roof falling inwards and those from the lower tier falling outwards.66 But this is just speculation on their part. Additionally it should be noted that recreations of the palace exist where it has both a single and two-tiered roofs and neither should be thought of as definitive.

Also of interest regarding the roof are the curious symbols that were made on the inner side of the tiles. Levasheva and Evtyukhova first noted this and compared them to the Orkhon runes found on the stele erected by the Second Turkic Khaganate in the 8th century.67 They note that Kiselev, who worked extensively on the archeology ancient Turks, believed the Orkhon runes possibly had foreign origins and that these symbols found at the Tasheba palace were possibly their antecedents.68 Conversely, Kyzlasov believes there is no connection between the two, and notes similar symbols were found craved into animal bones from the Tashtyk period.69 Considering the geographic proximity of the Minusinsk Basin to the Mongolian Plateau and the general similarity between the symbols and the Orkhon runes, in the opinion of this author the possibility of a connection should not be ruled out.

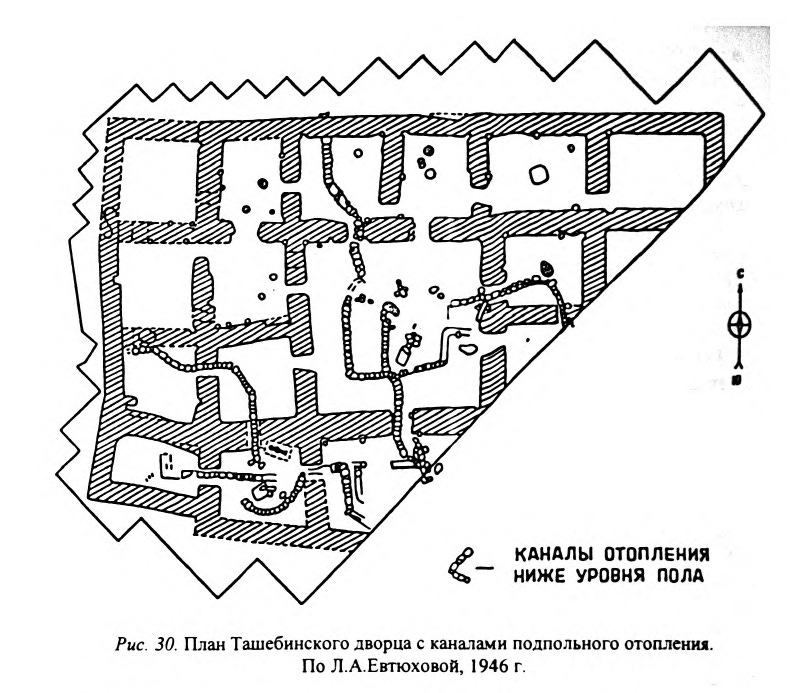

The Floor and Underground Heating System

The floor of the palace was likewise adobe, and was 20-25cm thick.70 Underneath the floor there was an extensive system of canals and ducts which served as the palace’s heating system. These ducts were dug 30-60cm deep beneath the clay adobe floor.71 Similar to a Korean ondol or a Manchurian kang, hot air originating from a furnace would have travelled through ducts under the floor, thereby heating the building. The ducts were covered by stone tiles that were transported to the palace from a nearby mountains 15 km away.72 During the initial excavation, Levasheva and Evtyukhova were unable to locate the furnace or determine how exactly the hot air was generated.73 That being said, the existence of the heating system and its purpose are not debated.

While these ducts linked into nearly every room of the palace, presumably the system did not fully work, or at least did not properly heat every room in the palace. In some rooms the clay floor was scorched and the remains of hearths in the form of stone slabs were found with traces of fire exposure.74 Braziers with hot coals were also found in the central chamber, which Levasheva and Evtyukhova argued were also for heating.75 Kyzlasov on the other hand argued these were for religious or ritual proposes. Moreover, the heating was presumably rebuilt or modified. Kyzlasov argued that initially the ducts were poorly ventilated, with the hot air becoming trapped and failing to flow properly due to winds from outside the building blowing into the chimney. The system was modified with additional branches that presumably improved air flow.76 Levasheva and Evtyukhova argued that the heating canals were altered to such an extent that the pattern of air flow was changed in some places.77

Again, this heating system is entirely unlike anything found in China that dates to the Han Dynasty, nor does it have any analogies in other ruins from the Xiongnu empire.78 Kyzlasov believes the heating system also had its origins in Central and Western Asia, comparing it to similar techniques found in Roman and Parthian baths, ancient Chorasmia (the modern Khiva oasis) as well as later Arab hamam steam baths. He also claims similar heating system have been found at the Andronovo site of Atasu near modern day Karaganda in central Kazakhstan, which existed from the 14th to 12th centuries BC, as well as other similar systems from sites that existed in the Middle Ages, namely on the Ob River from the 6th and the 7th centuries.79 Additionally, it should be noted the oldest heating system of this kind was found at the ruins of Mari, a Sumerian site in modern say Syria, which dates to the 18th century BC.80

The Rooms

The building was rectangular shaped, with 20 rooms.81 The central chamber was the largest, covering a space of 132m2, and was adjoined by halls leading to it.82 Kyzlasov argues that this central chamber was likely used for religious purposes due what appeared to be fire-alters and the remains of burnt offerings in the room.83 Kyzlasov believes these were Zoroastrian fire worshiping ceremonies practiced either by converts or by believers who were resettled here by the Xiongnu.84 According to him, smoke from these ceremonies would rise up to the upper ceiling of the palace, which symbolized the heavens.85

Conclusion – Not a Chinese Palace, but a Central Asian One

In conclusion, it can be said for certain that the statement by Evtyukhova and Levasheva that the palace was “built by Chinese for Chinese” is at the very least half wrong.86 In fact the statement that the building was a “Chinese palace” might entirely be a misnomer. Only the roof tiles are clearly Chinese in origin, and even then Kyzlasov argues they could have been created either by Xiongnu or other craftsmen simply using Chinese characters.87 The rest of the building, including the walls made from abode compressed clay (pakhsa) and the underground heating system have clear origins from Central Asia.

Kyzlasov believes the craftsmen who built this palace were likely either Sogdians from Central Asia who came to the Yenisei initially for commercial purposes, or Tocharians or Yuezhi that the Xiongnu resettled in the Minusinsk Basin.88 For the latter, he specifically points to the Xiongnu campaigns against the Yuezhi and the Tarim states from 211-168 BC as being when those people might have been forcefully relocated there.89 The theory that the craftsmen who built the palace were permanently settled in the region is very convincing, as it would explain the multiple repairs and renovations to the underground heating system.90

Moreover, the craftsmen being from Central Asia would also explain the possible Zoroastrian rituals in the palace (although admittedly, it is a big if whether these were Zoroastrian rituals or something entirely different). Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Persian Achaemenid Empire and spread throughout its satrapies, including those of Sogdia and Bactria in Central Asia. The Sogdians in particular established long distance trade networks based on scattered diaspora communities that stretched from Persia to China, and possibly into Siberia as well. It is also known that since very ancient times trade routes existed that connected Central Asia to the lands north of the Sayano-Altai Mountains. One route in particular ran across the northern face of the Altai, going over the Irtysh River and crossing the Ob River near where the modern day city of Biysk is located. Kyzlasov notes that the 10th century Persian geographer Hudud al-'alam wrote that the Yenisei Kyrgyz worshipped fire. During the Middle Ages in particular, the Sogdians spread Buddhism, Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity into China and the steppes, thus the possibility they also brought Zoroastrianism to south Siberia is not at all outlandish.

The Tasheba City

The Tasheba palace was merely one building in a larger settlement that was seemingly modeled on Chang'an, the capital of China’s Han Dynasty.91 The total size of the city was about 10 ha, and shaped as a rectangle.92 The streets appeared to have predominately run west to east, similar to other Chinese cities at the time. The standard south-north orientation of streets was only adopted during the Wei Dynasty (386–535 AD). The settlement had to two gates that faced south and one that faced north, which was similar to other Xiongnu settlements found in the Trans-Baikal region. Similar to Chinese settlements, the Tasheba city was seemingly subdivided into urban quarters.93

Other than the palace no other buildings survive from the city, only some dugout pit and the outlines of residential neighborhoods could be determined. It is likely that all of the other buildings were earthen dugouts with wooden structures on top.94 A general idea of what the city looked like can be gleaned from the Malaya and Bolshaya Boyarskaya petroglyph drawings which were discovered about 100 km north of Abakan on the left bank of the Yenisei River and date to the Tagar-Tashtyk transition period.95 In fact it is fully possible that the Tasheba city is what is being depicted there.

Tasheba city was only partially surrounded by walls. Similar to the walls of the palace, these walls were also made of pakhsa compressed clay. Seemingly these walls and other defenses were only partially completed before the palace and the city were destroyed in the late 1st century BC. In other words, the city walls were never fully built. One section of the wall that was discovered ran south-south-west to north-northeast. Only 584.56 m of this wall were found. It was 3 m wide, and flanked by ditches on both sides, both varying from being 0.8 to 1.2 m wide at various points.96 South of this wall flowed the Abakan River which likely functioned as a natural moat defending the city. A wooden stockade likely stood between the wall and the river, screening the wall. West of the palace about 500 m away stood a tower. The northern wall of the city was 2 m wide, with its eastern end terminating at the base of a tower that was never fully erected.97

Additional fragments of the wall were found spend over 665 m away to west. The southern wall was found 350 m away from the entrance of the palace. The northern wall was possibly about 105 m away from the palace. Kyzlasov believes the entirety of the Tasheba city was likely 800 m x 600 m.98 But again, it must be emphasized that the exact dimensions of the city are unclear due to insufficient archaeological remains.

The palace was likely located somewhere north of the city center, but its exact location within the city is uncertain due to the incomplete nature of the city walls, making the precise layout of the city a mystery.99 A space of about a 100 m in front of palace likely remained empty, and presumably this was a parade square, or possibly even the city’s central square. Residential housing located 100 m southwest of palace was discovered in 1987 and researchers believe the palace’s servants and attended lived here.100 It is also believed that the area inside the city walls was not entirely occupied by housing. Instead, urban density was quite low, certainly far lower than what existed in Chinese cities, and many open and barren spaces existed within the walls of Tasheba city. Chinese built large walled enclosures with the assumption that the enclosed spaces would be gradually populated over time as the city grew. This was likely the assumption made by those who planned and built the Tasheba city as well.101

The city was likely the administrative center of the Xiongnu empire in the Minusinsk Basin. Not only would it have housed the local governor and military garrison, it also would have housed markets. To can understand what the Xiongnu would have used this settlement for by examining what the Russians used their settlements in Siberia for centuries later. While expanding also Siberia the Russians built several fortresses and small outposts. These settlements served as strong points that housed Cossacks, who would periodically go out and collect “yasak” tribute from Siberia’s native peoples. This tribute largely came in the form of furs. Additionally, hostages from native yasak paying tribes, usually family members of the tribal elite, were taken by the Russians and were kept in Russia’s fortified settlements.102

It is very likely the Xiongnu interfaced with native Siberian peoples similar to how Russians later did, and used the Tasheba city as a point to collect tribute from the Dingling and as a place to hold hostages. The Russians themselves learned of such practices from the steppe nomadic peoples they came into contact with, and these traditional methods of nomadic imperial management remained largely constant throughout time. Moreover, several other unrelated cultures practiced forms of hostage taking, such as the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Chinese dynasties, both of whom required family members of subordinate states to reside in their capitals.

It also should be emphasized again that the metals and grain of the Minusinsk Basin were likely sought after by the Xiongnu and collected as tribute. In later centuries the Minusinsk Basin became a center of weapons production thanks to the rich ore deposits. The Xiongnu surely would have wanted these metals in order to supply their own war machine. Grain was particularly important as it would allow the Xiongnu to both maintain urban settlements, as well as serve as a backup form of nutrition in case of mass die-offs of their herds due to climatic shocks or disease.

One of the main items the Xiongnu sought from Han China as a form of tribute was grain supplies. These supplies allowed the Shanyu to maintain a large camp replete with many luxuries and forms of entertainment that typically only a sedentary culture could support. For example, in 119 BC when Han forces overran the imperial camp of the Xiongnu they found massive grain supplies that were able to feed the 50,000 strong Han army.103

Near the palace a stone horse head was found, presumably broken off from a larger statue which likely dates to the Tagar-Tashtyk transition period. Kyzlasov assumes this statue was apart of Li Ling's tomb which was built by his son who was born around 96-95 BC. He notes that Han military tombs often featured a statue of the warrior's war horse.104

Unfortunately, the Tasheba palace and city were totally destroyed in 1990’s by the local government, with the ruins and adjacent areas being turned into someone’s personal estate.105

The Palace’s Artifacts

A wide range of artifacts were discovered in the ruins of the Tasheba palace, including axes, icepicks, a green jade vase, a green jade dish, and ceramic dinner and kitchenware. The ceramic dishware was noted as being very similar to other ceramics found at Xiongnu sites in Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal region. A claw pendant made from white jade also discovered. The jade from this artifact was possibly from the city of the Khotan in the southwestern corner of the Tarim Basin, which has been famous since ancient times for its white jade.106

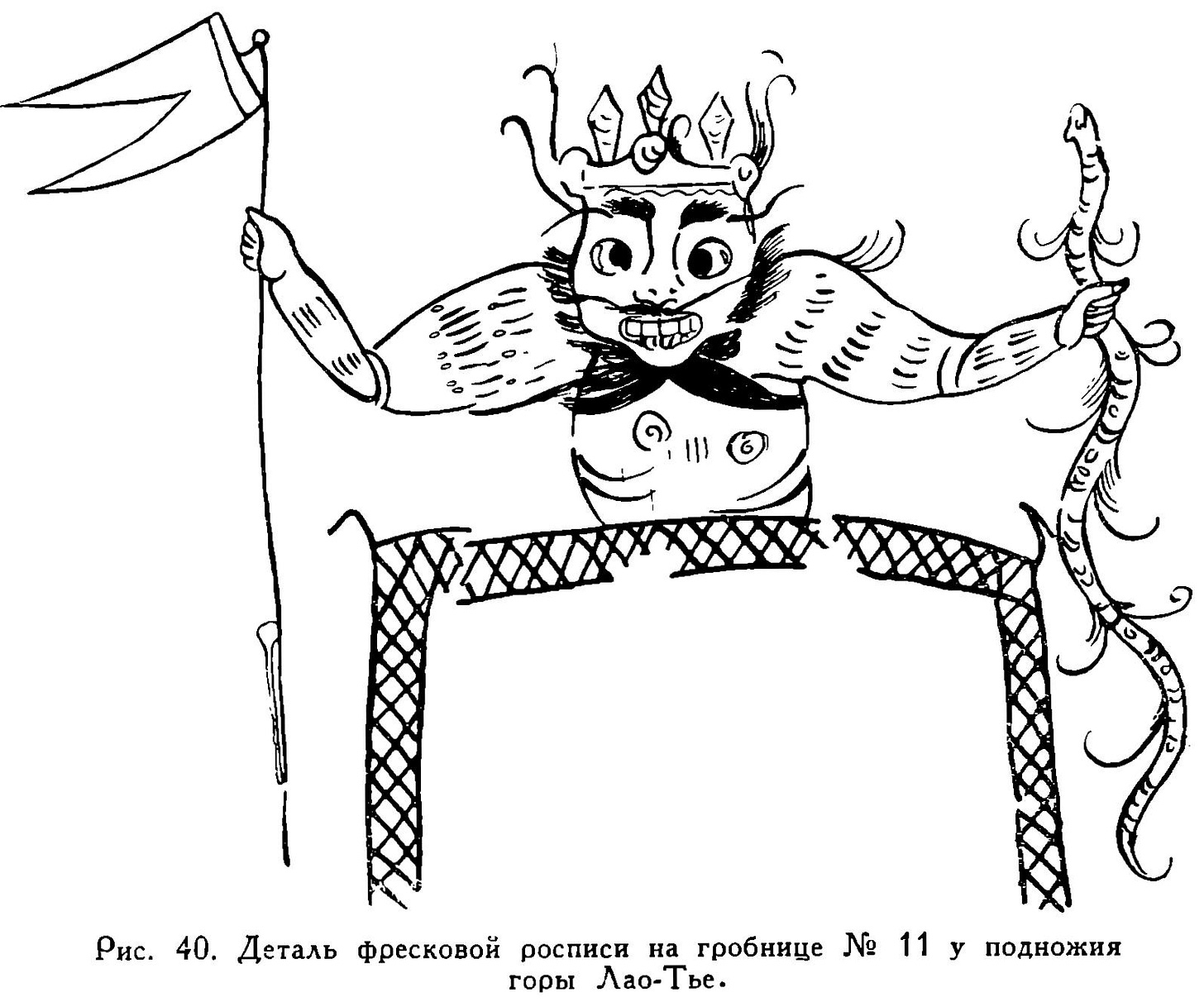

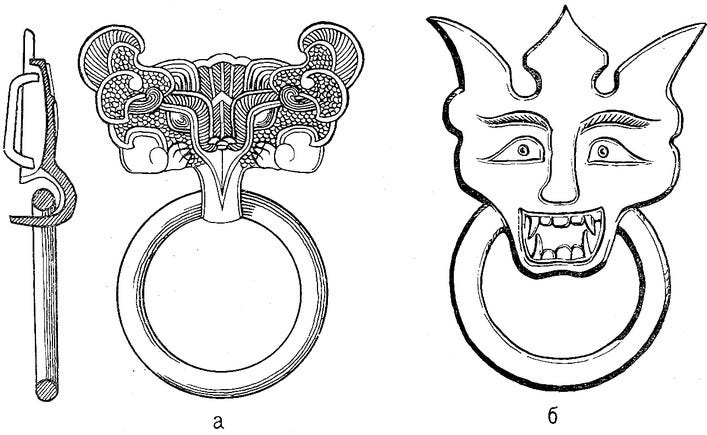

Probably the most ironic artifact recovered were the bronze door handles made in the image of a monster with horns, grinning teeth, a flowing mustache and a large ring meant to be the door handle through its nose. The handles were found at two places in the palace where doors once existed. The face of the handle with one broken horn appears to be smiling more than the other.107 Some debate exists on what this face is meant depict. Some have argued that faces depict Caucasian features, namely the large nose, while others have argued they depict Asian features.108 In the view of this author, the faces are simply monsters with a generally human-like visage. Levasheva and Evtyukhova note the faces on the door handles resemble engravings found at the Han Dynasty tombs at Mount Laote near Port Arthur on the Liaoning Peninsula.109

The spiral figure that appears above door handle faces is quite interesting and similar patterns can be seen on some of the Tashtyk mask. Komissarov and Mitko argue that the door handles were based on Chinese designs that were made in a way that resembled local people.110 As the majority of the people in the Minusinsk Basin were Caucasian in appearance at the time, this would explain why face has such a large nose.

Reportedly, residents of Chapaevo still to this day occasionally find ceramic shards, animal bones and other artifacts in their gardens.111

But Who Was the Palace Built For? Theories Regarding the Illusive Resident of the Tasheba Palace

Since the palace’s discovery in the 1940’s the Li Ling theory regarding who the palace was built for has remained dominate and widely accepted, at least in Russian language scholarship, which constitutes nearly all of the research on the palace. Indeed, the notion that Li Ling lived on the shores of the Yenisei has been regarded as true by Russian Sinology for quite some time. Nikita Yakovlevich Bichurin, the father of Russian Sinology himself wrote that: “Li Ling remained with the Huns and received lordship of the Khyagas,112 where his descendants reigned nearly until the time of Chingis Khan. The Shanyu paid him his due respects and wedded his daughter to him.”113 The palace’s main researchers, Levasheva and Evtyukhova, as well as Kyzlasov, all believe the Li Ling thesis. Regardless of what others believe, it is the current author’s opinion that the Li Ling should not be accepted uncritically. There are also additional theories regarding who the palace was built for which point to figures other than Li Ling.

It is unnecessary to recapitulate the story of Li Ling at length here again, but certain details should be reexamined. The primary source of information on Li Ling that says he was sent to the Yenisei and served as the regional viceroy for the Xiongnu comes from the Tangshu, or “Book of Tang”, a Chinese chronicle written during the 11th century during the Song Dynasty. Russian researchers regularly cite Bichurin regarding this issue.114 Information regarding the Yenisei Kyrgyz as being the descendants of Li Ling is also entirely based upon Chinese sources dating to the Middle Ages.115

The problem here is obvious. It is entirely possible that the story of Li Ling being exiled to Siberia is nothing more than a romantic myth concocted by Chinese chroniclers nearly a thousand years after the fact. The possibility that Li Ling never even stepped foot anywhere near the Minusinsk Basin must be considered. That being said, simply because the evidence is flimsy does not necessarily make it untrue.

The ancestral claims made the Yenisei Kyrgyz likewise deserve scrutiny for three reasons in particular. First, the Chinese courts operated on terms of strict protocol regarding hierarchy. By claiming a familial connection to the ruling Li family of the Tang Dynasty, the Yenisei Kyrgyz envoys were likely aiming to secure special privileges for themselves, which they did receive. Second, the Yenisei Kyrgyz only established uninterrupted contact with the Tang court after they had destroyed the Uyghur Khaganate in 840. In the years following 840, the Yenisei Kyrgyz rampaged across the Mongolian plateau in a quest to eliminate the remaining Uyghur tribes. Meanwhile, a large horde of Uyghur refugees flooded to the northern frontiers of the Tang Dynasty’s which created a serious threat to the security of the Tang state that had been gravely weakened by the An Lushan Rebellion of the mid-8th century. It is entirely possible that the Tang court sought to flatter the Yenisei Kyrgyz by indulging them in their claims to being related to the Li family in order to secure their cooperation against the remaining Uyghur tribes. Third, contra the reason given by Yenisei Kyrgyz for the appearance of Asian features among them, that Li Ling and his Chinese garrison mixed with the local population, we have another possible explanation for this, one that is at least equally plausible. As mentioned above, the Xiongnu at the end of the 3rd century BC resettled the Jiankun people in the Minusinsk Basin, and this is possibly why some Yenisei Kyrgyz had Asian blood.

An alternative theory to the Li Ling thesis is that the palace was built for a false emperor who launched a failed rebellion against Wang Mang and his Xin Dynasty. From 9 to 23 AD Wang Mang temporarily usurped the Han Dynasty and founded the Xin Dynasty, which experienced widespread rebellion and destabilization. The main proponent of this theory is A.A Kovalyov. He believes that the palace served as the residence for the false emperor Lu Fan, a civil servant who claimed descent from the Han Emperor Wu and launched a rebellion in Gansu at end of Wang Mang’s rule. For a time Lu controlled much the Western Lands and managed to establish diplomatic contact with the Xiongnu. In 36 AD Lu was forced to flee to the Xiongnu due to internal conflict within his state, but returned to China in 40 AD. He was granted amnesty and was soon given an appointment in northern Shanxi, only to start another rebellion. This also failed and in 41 AD he was once again forced to flee to the Xiongnu. He reportedly lived the remaining 10 years of his life among the Xiongnu.116

According to Kovalyov, the Tasheba palace was built specifically as a residence for the false emperor Lu Fan and the city was a colony of Lu’s followers who fled to the Xiongnu with him. The evidence he points to for this assertion are that the Chinese inscriptions on the roof disks. The disks used the character for Chang’an which correlates to the Wang Mang era. Chang’an was the capital of the Han Dynasty, but under Wang Mang its name was changed Chang’le, with the character for “chang” being changed as well.117 Sevyan Izrailevich Vainshtein and Mikhail Vasilivich Kryukov likewise agree that the character for “chang” means the palace was built at least century after Li Ling was captured.118 Thus, Kovalyov argues that these disks were made by Chinese craftsman working in accordance with the changes made by the Xin regime, and that the “Son of Heaven” refers Lu Fan.

This theory is not particularly convincing for several reasons. First, why would the Xiongnu keep their puppet emperor far away in the distant fringes of their empire? Would it not make more sense to keep Lu Fan in the imperial camp under close supervision and where he could be made of use more readily? If an opportunity and reason presented itself to send Lu back to China as a Xiongnu proxy he would need to be kept close enough to China. In Siberia he was useless. Moreover, the palace appears to have been intended for a permanent resident and not a temporary one. Second, why would the Xiongnu brother to construct such an elaborate palace in such a distant place for a figure who in grand scheme of things was not very important. Li Ling, as well the princess Yimo, the other contender who will be discussed below, were both much more important and worthy of such a palace. Lastly, the references to “Son of Heaven” were likely made towards the Shanyu. The nomads north of China shared many of the same political motifs with China. In fact, some believe the Chinese concept of a “Son of Heaven” came from the nomads.119

The question regarding the characters on the disks is more difficult to resolve. Vainshtein and Kryukov agree that this issue discredits the Li Ling thesis, and argue that the building was certainly made long after Li Ling had passed away.120 It is possible that those disks were made after the palace was built, or that the character for “chang” that the disks use was not unheard of in the 1st century BC. This is a question that can only be answered decisively those with impeccable knowledge of the history of Chinese characters and their usage during the era of the Han Dynasty.

Vainshtein and Kryukov offer a theory of their own regarding who the palace was built for and who resided there. According to them, it was home to the Xiongnu princess Yimo, the daughter of Shanyu Huhanye and the Han Chinese princess Wang Zhaojun. The Zhaojun Princess married the Shanyu in 33 BC, giving birth to two sons and two daughters. In 31 BC the Shanyu Huhanye died, and as according to nomadic custom she married his elder brother who became the new Shanyu. With her new husband, Zhaojun gave birth to another two daughters, the elder being the princess Yimo. Yimo was later sent to China, to the court of Wang Mang, but was subsequently returned to the Xiongnu. She then married Syuibudan, the Xiongnu viceroy over the “lands of the right,” in other words the eastern half of the Xiongnu empire. According to Vainshtein and Kryukov, the palace was the headquarters of the viceroy of the right and thus also housed Yimo.121

Vainshtein and Kryukov reject that the palace ever housed the Zhaojun Princess herself as it was too far away from the Shanyu. This is logical. But the claim regarding Yimo and the headquarters of the “lands to the right” being associated with the Tasheba palace raises the same question that the Lu Fan theory raised: why would any of these people live all the way in Siberia? This theory is particularly spurious because it makes zero sense that the headquarters of the viceroy of the Xiongnu’s right wing would be located in the distant and remote region of the Minusinsk Basin. It would make far more sense for the headquarters to be located around modern day Khvod in the southeastern Altai region or at Barkol just north of Hami.

In the opinion of this author, the theories regarding Lu Fan or Yimo as the palace’s residents are even less believable than the primarily theory that it was Li Ling. Lastly, Levasheva and Evtyukhova, as well as E. B. Vadetskaya, argued that the palace and settlement were connected to a diaspora of Chinese merchants who settled in the Minusinsk Basin and that the city was a fortified settlement meant to protect these merchants.122 This is a very plausible theory, although as already discussed, the merchants in question were more likely from Central Asia than China.

The Palace of Li Ling and the Collapse of the Xiongnu Empire in South Siberia

In the opinion of this author, if the palace was built for any known historical figure, it was most likely Li Ling or his children. Due to the general scarcity of information we likely have to accept the Chinese chronicles at their word. And even if the story of Li Ling is nothing more than a romantic legend it at least adds an interesting back story to an otherwise featureless structure from more than 2000 years ago.

The greater mystery, and one that has been curiously overlooked by researchers, is how or why the palace was ruined. In the opinion of the current author, the seemingly unquestioned explanation that the palace was destroyed by the floods appears too simple on the face of it. A flood definitely did occur, as it resulted in the formation of the hill over the palace ruins. We also know for certain this flood occurred either during the Tagar-Tashtyk period or very early during the Tashtyk period due to the graves found in the walls of the palace which date to the early Tasthyk period. But what has been curiously overlooked is that the palace was seemingly destroyed at about the exact same time that Xiongnu empire collapsed in the Minusinsk Basin.

The Han Dynasty went on the offensive against the Xiongnu beginning the in 130’s BC. The envoy Zhang Qian was sent to the Western Lands in such of allies, and from 120 to 100 BC the Han “cut off the right arm” of the Xiongnu by conquering Central Asia. These campaigns proved extremely costly and did little to actually weaken the Xiongnu, so Han shifted back to the defensive. Due to their isolation and lack of external threats which would unify the tribes, Xiongnu power began to rapidly decline under the Qiedi Shanyu, who reigned from 101-96 BC.123 By the 70’s BC the Xiongnu’s subject peoples began to rebel. In 78BC the Wuhuan nomadic people to the east revolted, followed by a joint attack on the Xiongnu by the Wusun and Han in 71BC. Around this time a bad winter killed off a large portion of the Xiongnu’s herds causing famine and a revolt broke out among the Dingling in the Minusinsk Basin. This series of escalating crises culminated with the death of the Huyandi Shanyu in 68BC, which was then followed by a civil war in 60BC.124

It should be noted that Li Ling reportedly died in 75 BC.125 Presumably, if the legend is to believed, the death of the Xiongnu’s prestigious viceroy from China resulted in local instability in the Minusinsk Basin. With the passing of such an authoritative figure, combined with the other crises occurring within the Xiongnu realm, the local Dingling people saw a chance to revolt. The Xiongnu were able to temporarily regather themselves after 54 BC, when they made peace with China and submitted.126 Nevertheless the Xiongnu’s empire only weakened further, and in 40 BC they were forced to evacuate from the Minusinsk Basin. Presumably the local Dingling and Jiankun created a new state of their own to fill the void.127

The timing of these events is very coincidental with the estimated time frame of when the palace was destroyed. Again, the presence of the early Tashtyk graves on top of the palace ruins means that the palace was destroyed sometimes around the birth of Christ. It appears the palace was destroyed at the same time Xiongnu’s power collapsed in the region, or thereafter.

Might it be possible that the palace was destroyed due to a local rebellion against the Xiongnu empire? Li Ling’s successor likely lacked the respect and authority he did. The fact that walls of Tasheba city were not completed is a very significant fact. The palace and the settlement were not properly fortified. It means the palace and its residents were more vulnerable than they otherwise would have been. Another possibility is that flood which created the hill was caused by a local rebels who destroyed a nearby dam, causing the flood. This is all speculation of course, but the timing of the palace’s destruction is extremely noteworthy. Russian researchers do not voice anything regarding this question. In fact they seem totally uninterested in the internal goings on within the Xiongnu and its relations with China. This question will likely never be answered decisively, but possibly with greater research into the Tagar-Tashtyk transition period better informed speculations can be made.

Conclusion

Countless buildings and historical sites similar to the Tasheba palace have existed in the past but have unfortunately been completely lost to time. Most buildings were made of wood and either were burned or quickly rotted away. Those made of stone were often dismantled piece by piece, their materials recycled and reused to construct new dwellings and structures. Others saw great cataclysms such as war and natural disasters and were totally destroyed. It is rare that any buildings from the past survived long enough for modern people to see them, especially those constructed in regions where wood was the primary building material.

This palace is likely only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the development of civilization in Siberia. It is known that the Uyghurs built several fortresses across Tuva, Por-Bazhyn being the most famous. Likewise, the Turkic Khaganates built fortress on the trade routes that crossed the Altai Mountains, such as the Yalomanskoe settlement on the Katun River. Even older Scythian sites have been found at Arzhan and Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains. It is not leap to conclude that nomadic empires on the steppe regularly reached into the northern forests of Siberia and likely even as far as the taiga. As it stands today, nearly all the research surrounding this topic is written in Russian, and what is known is highly fragmentary due to the sacristy of written and material sources. The Tasheba palace is a testament to this. An important task going forward will be to introduce Russian language research on this topic to the English speaking world and connect it to preexisting research on the empires of the steppes which is quite extensive as it is. This essay on the Tasheba palace is hopefully a powerful step in that direction.

Bibliography

The single best text on the Tasheba palace is the book “Гуннский Длворец на Енисее” (“Hunnic Palace on the Yenisei” (Russians refer to the Xiongnu as Huns)) by Leonid Romanovich Kyzlasov, published in 2001. In terms of English language texts, there is “The Urban Civilization of Northern and Innermost Asia”, also written by Kyzlasov and translated into English by the Institute of Archeology of Iasi in Romania, in 2010. It seems that excerpts from “Гуннский Длворец на Енисее” were translated and included in this volume, in addition to other information.

Barfield, Thomas J. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

Beckwith, Christopher. The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Bridgman, Timothy P. Hyperboreans: Myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

Ban, Gu, and Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1979.

Bynner, Witter (Translator). 300 Tang Poems. University of Virginia (online edition), 1997.

Chen, Hao. A History of the Second Türk Empire (ca. 682-745 AD). Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Drompp, Michael Robert. “The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest.” 2002.

Johannes Van Donzel, Emeri, and Andrea Schmidt. Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam’s Quest for Alexander’s Wall. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Kyzlasov, Leonid Romanovich. The Urban Civilization of Northern and Innermost Asia: Historical and archaeological Research. Translated by Gheorghe Postică. București: Editura Academiei Române, 2010.

Slezkine, Yuri. Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Вайнштейн С. И., Крюков М. В., “«Дворец Ли Лина», или конец одной легенды”. Советская этнография. 1976, № 3. 136/137.

Евтюхова, Л., А., Левашева В. П. “Раскопки Китайского Дома Близ Абакана (Хакасская А.О.).” КСИИМК. Вып. XII. М.-Л., 1946, 72–84.

Евтюхова, Л., А.“Развалины Дворца в «Земле Хягяс».” КСИИМК. Вып. XХI, 1947, 79–85.

Ковалёв, А.А. “Китайский император на Енисее? Ещё раз о хозяине ташебинского «дворца».” Этноистория и археология Северной Евразии: теория, методология и практика исследования. Иркутск: 2007. С. 145-148.

Комиссаров, Сергей, и Олег, Митько. “"Дворец Ли Лина": реалии и гипотезы.” Великий Шелковый Путь: Культурное Наследие и Развитие Контактов: Сбю Статей. Новосибирск: НБУ, 2020.

Кызласов, Леонид Романович. Гуннский дворец на Енисее. Москва: Восточная литература, 2001.

See, “Hyperboreans: Myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts”, Timothy P. Bridgman, 2005.

See, “Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam’s Quest for Alexander’s Wall”, Emeri Johannes Van Donzel and Andrea Schmidt, 2014.

Евтюхова, “Развалины Дворца в «Земле Хягяс».”, 79.

Евтюхова, Левашева, “Раскопки Китайского Дома Близ Абакана (Хакасская А.О.).”, 72-73.

Ibid., 74.

Кызласов, “Гуннский дворец на Енисее”, 10-11.

Ibid., 14.

Ibid., 15.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, “«Дворец Ли Лина», или конец одной легенды”, 136.

Кызласов, 10.

Ibid., 126.

Barfield, “The Perilous Frontier”, 33.

Ibid., 36.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 36.

Ibid., 48.

See, “Ban, Gu, and Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty”, 1979.

Кызласов, 136.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 83.

Кызласов, 131.

Ibid., 138.

Ibid., 133.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 82.

Ковалёв, “Китайский император на Енисее? Ещё раз о хозяине ташебинского «дворца».,” 147.

Barfield, 29.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 83.

Drompp, “The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest.”, 480.

Кызласов, 133.

Drompp, 481.

Ibid., 482.

Кызласов, 130.

Ibid., 126.

Евтюхова, 79.

Кызласов, 117.

Комиссаров, Митько, “"Дворец Ли Лина": реалии и гипотезы.”, 56.

Кызласов, 104.

Комиссаров, Митько, 48.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 73.

Евтюхова, 84.

Кызласов, 29.

Ibid., 18.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 144.

Kyzlasov, “The Urban Civilization of Northern and Innermost Asia,” 244.

Евтюхова и Левашева, 72.

Кызласов, 62.

Ibid., 61.

Ibid., 64.

Ibid. The quote is from: В.Л. Воронина “Архитектурные памятники древнего Пянджи- кента”, Таджикская археологическая экспедиция. МИА. № 37. М.-Л.С . 118.

Ibid.

Евтюхова, 82.

Кызласов, 117.

Kyzlasov, 190.

Евтюхова и Левашева, 74.

Ibid.

Комиссаров, Митько, 53.

Л.А. Евтюхова, 82.

Кызласов, 72.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 78.

Кызласов, 109.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 142.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 76.

Kyzlasov, 201.

Ibid., 203.

See, “A History of the Second Türk Empire” by Hao Chen for both a narrative history on the Second Turkic Khaganate and a modern translation of the Orkhon inscriptions.

Л.А. Евтюхова, В.П. Левашева, 76-77.

Кызласов, 75.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 74.

Кызласов, 78.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 75.

Ibid., 74.

Комиссаров, Митько, 49.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 76.

Кызласов, 81-82.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 75.

Кызласов, 87.

Ibid., 85.

Kyzlasov, 215.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 137.

Комиссаров, Митько, 48.

Кызласов, 102.

Ibid., 103.

Kyzlasov, 228.

Кызласов, 126.

Ibid., 147.

Ibid., 64.

Ibid., 65.

Ibid., 87.

Kyzlasov, 197.

Кызласов, 122.

Ibid., 193.

Ibid., 120.

Ibid., 120.

Kyzlasov, 195.

Ibid., 188.

Ibid., 196.

Ibid., 193.

Кызласов, 29.

Kyzlasov, 197.

See, “Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North,” Yuri Slezkine, 2016.

Barfield, 48.

Кызласов, 125.

Кызласов, 6.

Ibid., 54.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 80.

Комиссаров, Митько, 51.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 81.

Комиссаров, Митько, 51.

Kyzlasov, 197.

Another way to say Xiajiasi or Yenisei Kyrgyz.

Кызласов, 114.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 148.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 84.

Ковалёв, 145.

Ibid., 146.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 145.

See, “The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China,” 2023.

Вайнштейн, Крюков, 146.

Ibid., 147.

Евтюхова, Левашева, 83.

Barfield, 58.

Ibid., 59.

Кызласов, 133.

Barfield, 60.

Кызласов, 131.

Fascinating and well written