The Ruins of Por-Bazhyn - Dmitri Klements, 1891

Translation of the first written account of the medieval Uyghur monastery-fortress found in Tuva

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Below is a translation of an excerpt from “Археологический Дневник Поездки в Средюю Могнолию в 1891” (Archaeological Diary of the Trip to Central Mongolia in 1891) by Dmitri Alexandrovich Klements. The source for the translation can be found here, on pages 68 - 72.

Dmitri Klements was a born in 1848 in the Saratov Oblast on the Volga River. As a young man he was a Narodnik, a revolutionary movement in Russian Empire during the latter half of the 19th century which advocated for the intelligentsia to go down to the villages and instill revolutionary fervour among the peasants who had been recently liberated from serfdom. After a period of emigration, Klements returned to Russia and was arrested and exiled to Yakutia in northern Siberia. On the way there he fell ill and ended up spending his exile in Minusinsk, in town in southern Siberia on the Yenisei River, south from Krasnoyarsk. While there is befriend the founder and head of the Minusinsk Regional Museum, Nikolai Mikhailovich Martyanov, and participated in several research expeditions to the Altai and Sayan Mountain ranges, which divide Siberia from the steppes to the south. Klements ended up staying in Siberia after his term of exile was completed, and he became a pioneer in the study of Siberian ethnology, anthropology and archaeology. As stated in the subtitle of this post, he was the first European explorer to visit the ruins of Por-Bazhyn in the Tuvan highlands.

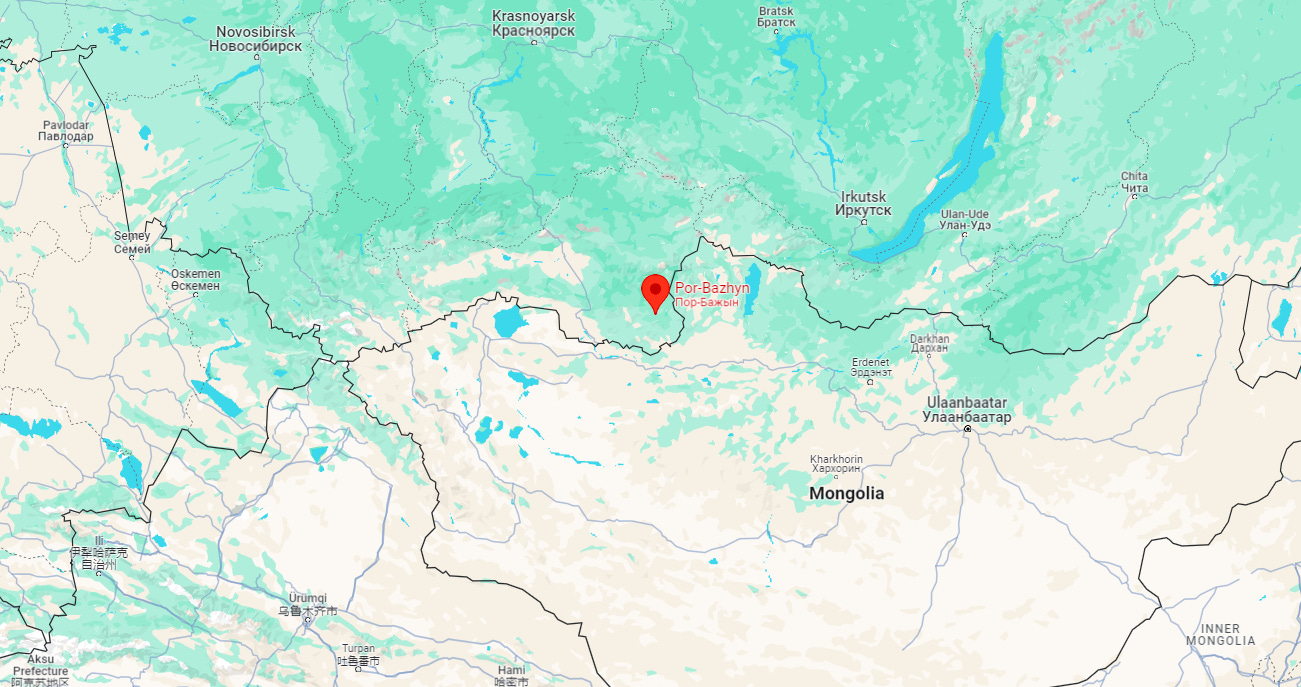

Por-Bazhyn (“Clay House” in the local Tuvan language) was built by the Uyghur Khaganate sometime after 750. The Uyghur Khaganate was a nomadic state that dominated the Mongolian plateau from 744 to 840, and can be said to be the most powerful nomadic empire in eastern Eurasia prior to the Mongols. During its reign the Uyghurs established a dominate and extortionist relationship with China’s Tang Dynasty, from which they extracted enormous amounts of wealth through an unequal trading relationship which very much mirrored and preceded the European exploitation of China in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is very likely the wealth extracted from Tang China was used to build Por-Bazhyn.

The site itself is located on an island in the middle of Lake Tere-Kol in the Sayan Mountains in eastern Tuva. After Klements, Por-Bazhyn only received further attention following the Second World War. The Soviet historian, archaeologist and ethnographer Sevyan Vainshtein conducted several expeditions to the site in the 1950’s and 1960's. In 2007-2008, attention was once again drawn to Por-Bazhyn thanks to efforts by Sergei Shoigu, who at the time was Russian Minister of Emergency Situations, and is half Tuvan on his father’s side. The site was reexamined with modern archaeological methods and technology, which allowed researchers to come to several conclusion regarding its construction.

The question of what exactly the Por- Bazhyn was, as well as how it was destroyed has long baffled researchers, but thanks to the research conducted in 2007-2008 some well grounded speculations can be made. Historically there were three main explanations for what Por-Bazhyn was: either a palace, a fortress, or a Manichean monastery.

The first theory that is was a palace can be dismissed out of hand I believe, as it makes no sense why such an elaborate palace would be build somewhere so remote and inaccessible.

The fortress theory is more plausible, but also unlikely. The Uyghurs created extensive fortifications across Tuva to defend the Khaganate’s northern frontier against the Yenisei Kyrgyz who lived in the Minusinsk Basin and would later bring about the downfall of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840 when they sacked the Uyghur capital of Ordubaliq (Turkic, “City of the Horde”), located on the Mongolian plateau in the Orkhon Valley near Kharkhorin. In the text below Klements refers to Ordubaliq by its Mongolian name Karabalasgun, which means “The Black City”. At least 15 Uyghur fortress have been discovered in Tuva, primarily along the Khemchik River, which were linked together by a “great wall” structure. Yet this explanation for Por-Bazhyn is problematic for the same reason why the palace theory is. Why would such a fortress be built in an already inaccessible mountain range?

The monastery thesis appears most likely to be true. It is believed this site was built shortly after the Uyghurs converted to Manichaeism in 762, during their invention behalf of the Tang Dynasty which saved it during the An Lushan Rebellion. Dendrochronolgists who studied Por-Bazhyn in 2007-2008 believe the site was built in the summer of 777, as they detected evidence of the “Miyaki event” on timber used in the site’s construction. The Miyaki event was a special solar flare which occurred in 775. Other researchers concluded that the site was destroyed soon after its construction in 779, as a consequence of a coup d'etat within the Uyghur Khaganate which brought an anti-Manichean fraction to power. Researchers noted that that main palace structure within Por-Bazhyn was heavily damaged by fire, which lead them to think that the site was destroyed by arson by those oppose to Manichaenism.

The team in 2007-2008 also figured out that the lake which surrounds Por-Bazhyn did not exist at the time of the site’s construction. In fact, researchers believe the lake has repeatedly appeared and disappeared throughout history as a result of occasional earthquakes which open and close spring waters within the permafrost. Traces of a road were found underneath the lake leading from Por-Bazhyn, further confirming that the lake did not exist at the time of the structure’s use.

Also, for clarification, the words “nor” and “kol” both mean “lake,” the former being a Mongolian word and the latter Turkic.

For a longer history of the Uyghurs, their relations with China, and the context surrounding Por-Bazhyn, see my essay “The Collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate”. For information on the Uyghur capital of Ordubaliq, see “Tamim ibn Bahr's ‘Journey to the Uyghur Khaganate’”. Currently I am researching the history and archaeology of the Uyghurs in Tuva, with a focus on the aforementioned fortresses that were built, with the title “The Uyghur Empire in Tuva.” I aim to have this published sometime this winter, while this post can be considered a preliminary report on Por-Bazhyn.

Lastly, Klements refers to a plan of the ruins that he made, and he includes symbols indicating buildings mapped out in his plan. I cannot find this plan, so unfortunately this translation is somewhat lacking, but modern recreations of the site make up for this I hope.

Remains of an Ancient Structure in the Land of the Uriankhai1 - Ruins at Teri-Nor

Breaking from the chronological order of the travel, I will begin with the ruins at Teri-nor, as it has survived better than others and should occupy the first place among the antiquities of the land of the Uriankhai.

Teri-nor is an alpine lake, from which flows the river Khakem, the left tributary of the Yenisei. It lies in an extremely wild place. Approaching the lake from the east, you must go down a steep path from a height no less than 1000 feet, while the lake itself lies as a height of 4000 feet above sea level.

There are no colourful larch groves covering the mountains here, the forests and vegetation are reminiscent of the dull Sayan taiga. The Uriankhais live here, cattle breeders and fishermen, and nearby to the north-west are hunters. The road to the lake from the west, east and south goes across rocky cliffs and high mountain ranges. Agriculture here is impossible, cattle breeding can only reach a particularly limited scale due to insufficient meadows; but fishermen and hunters enjoy the full scope of their activities. Along with the lake, fishermen have the upper Khakem available to them, which is rich in fish. There is not much to say about the animals. The lake is elongated from southwest to northeast; but its size on the map is greatly exaggerated: it lies in a deep basin, half of which is now dried out. Its size cannot be considered more than 20 verstas2 in length and 8 miles wide. Along the eastern shore of the lake there is a row of low islands; the lake itself is extremely shallow in its eastern half. To the west, where tall cliffs descend down to the lake, it can be expected to be deeper. For fishing the Uriankhais go about the lake on rafts by pushing into the bottom of the lake with poles. 3 verstas to the east-northeast from the kuren,3 lying in the southwestern corner of the lake is a flat island, entirely overgrown with derisun4 and reeds. This is the southernmost island – further to the south, east and west the water is clear. The island stretches to the north and has a small spit that goes 300 sazhen5 to the southeast.

Located on this island are ruins, which the local inhabitants call the palace of the Hong-Taiji,6 who, according to legend, once lived in the place where today the lake Teri-Nor is located. A great lama told this Hong-Taiji that when water begins flowing from the well dug near his palace he must get away from there as fast as possible, as waters will flood everything around him.And this did indeed happen: Hong-Taiji and his followers did not hesitate – their escape was so hasty that the prince’s doctor-lama dropped all of his medicine in a river and since then the river has been called Etin-Kol. Upon climbing up the mountain overlooking the lake, the Hong-Taiji looked back and saw that the entirety of his former lands were flooded with water.

The ruins are at the southwestern end of the island. From the southern corner of the ruins a narrow toe of the island stretches out 30 sazhens; along the southeastern wall of the ruins there is a narrow stripe of land; against the northeastern wall there is a small body of water that lies inside of the island; only to the northwest and north is there a wide strip of land in front of the ruins. The island’s soil is swampy and apparently in many places it is full of water. On dry elevation tall grass grows. This place is not often visited: there are no traces of any paths, nor is the grass trampled anywhere.

The ruins consist of the remains of a building, surrounded by tall clay walls. The walls form a quadrangle,7 stretching out from the southwest to the northeast. The walls are 139 sazhen long and 89 short. The width of the walls is unequal – from 3 to 5 sazhens, the height is 17 feet. The walls are very similar to the walls of Karabalgasun,8 with the only difference being that it is made with more lightly coloured clay. The southwestern wall is the best preserved; it has less cracks and due to erosion the inner facing side of the wall is very steep, while much of the outer side has crumbled away; but not as much as the southeastern wall: it consists entirely of separate high ridges that have been separated by cracks caused by water, which I strove, quite clearly I hope, to depict in the plan of the ruins. Here the external side of the wall is steeper; but the inner side is crumbling and is overgrown with meadowsweet, rose hip and bird cherry. In the middle of the northeastern wall there is a gate, which is already half in ruins. It can be noted that gate walls were narrowed as they raise up and in the courtyard there the ledges from the gateway. The northwestern wall is less in ruins than the southeastern wall; but the outer side of it is so overgrown with bushed and small larches, which make it difficult to recognize that is it as a man made structure. On the inner side in the southern half it is so pitted with separate earthen pillars tightly placed against each other; the northern half is less washed away and destroyed.

The inner building is not very well preserved. All that remains of it are embankments, traces of the lower parts of the wall and piles of clay.

Along the southeastern wall, starting from the southern corner, there are a row of separate buildings, 7 of them - aa, adjacent to the wall. The size of each cell is 91 feet in length and 70 feet in width. In other words, two embankments go along the walls, connected by a walkway.9 Inside each cell is a flat elevation B; along the edges of these elevated places the remains of clay walls can be noticed and piles of clay in the corners. Each cell was covered by a wall10 Y with a passage through the middle of it. Similar separated cells were built along the southwestern wall (a1, a1) and along the northwestern wall (a2 b1, a2 b1). Along the later, cells were built in two rows. All of these cells are similar B and only differ from the latter in terms of their size.

Within the courtyard and a bit closer to the southern side there is a round earthen platform A that is one arshin11 in height, joined by the isthmus C from a quadrangular platform B.

It was not the first time we encountered ruins of this type before. Let us remember the tall tower of Karabalgasun and the round platform in front of it, as well as the two ruined buildings at Khanyn-rol,12 connected by an earthen platform. This uniformity of form indicates the buildings had a similar purpose. Equally worthy of attention, is that such buildings were always built in the middle of the courtyard and surrounded by walls. If at least one of these buildings are proven to be a palace and not on the contrary a cathedral, then we will likely have the right to also say the same about the others. In front of the platform В we can see the round, flat, low terrace D. In addition to the listed remains from inside the courtyard, the remains of the clay wall E and E can also be mentioned, which lie in the northeastern part of the courtyard.

Who, not even having seen these ruins in real life but only their plan, will come to compare them to the plans of other old buildings in Mongolia, and will undoubtedly be amazed by the similarity with the ruins of Karabalgasun. The resemblance is so remarkable that one cannot help but come to the daring idea to restore what is lacking in one that the other has. There are some differences, for example – at Teri-Nor there is no corner tower; but despite that the resemblance in the arrangement of the internal buildings is striking. I have now seen quite a few monasteries in Mongolia; but I am convinced that if their plans were to be collected and compared, it would be hard to find two plans so similar to each other as those which I am speaking about. I will note one additional difference, which should strengthen the resemblance between them and will be useful for several considerations: at Teri-Kol there is no tall inner tower; it should be in the place designated in my plan with the letter A; but this only proves that Karabalgasun was rebuilt a few times, but this was not done for the buildings at Teri-Nor. I cannot recall here what the commander of the expedition thought about the tower at Karabalgasun – he believed that this is the remains of a pagoda built by Menke-khan in 1256. There are also no remains of any kurgans within the walls of the Teri-Nor ruins; there is only a small, granite plate F around the southeastern walls, without any inscriptions nor hollowed out.

It cannot be helped but to ask who built these buildings that lie on top of the remains that we are wondering about? Who chose for such a structure to be built in the unreachable Teri-Nor? The other architectural monuments that are known to us in the Uriankhai land lie in open places – where there is also taiga. It seems to me that one can absolutely answer this as such – not the Mongols, nor the Chinese, nor the Khitans13 or Zungars.14 More likely is that it is the same or a related people as who built ancient Karakorum.15 The Uriankhais have lived here since then, who call themselves Tuba, or Uyghur-ulus, and their language is Uyghur-khel.

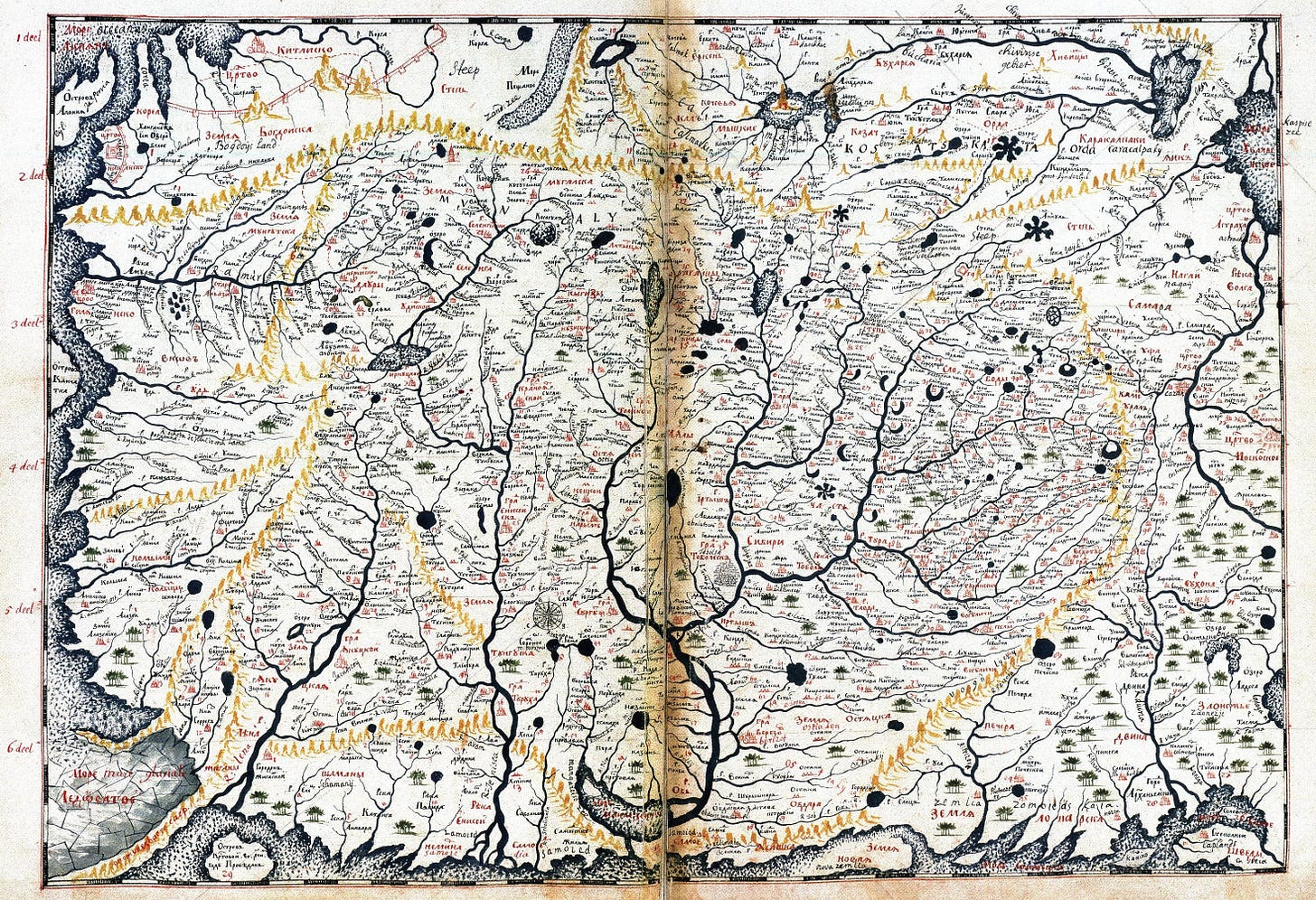

Let us recall, that these ruins were known to the Russians earlier than others: they were already noted in the Remezov’s atlas;16 it said that at lake Teri-Nor there are the ruins of a city with two walls. And I saw this city and I will conclude its description with words from the atlas of Remezov, “and what this city is and whose it was – we do not know.”

Mongolian word used for Tuvans and other Turkic speaking peoples to their north

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 km / 3,500 ft

A type of house, likely referring to a home of a native Uriankhai. I am not entirely sure of this translation, the original word is “от куреня”

A type of grass (Latin: Neotrinia splendens)

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.1336 m / 7 ft

This could either refer to the Mongolian word for “crown prince”, the ruling title of the Zungars, or to the second ruler of the Qing Dynasty and son of Nurachi

An open space enclosed on four sides. The short form of this word is “quad”, which typically refers to common squares at university campuses

“The Black Ruins”, the Mongolian name for he capital of the Uyghur Khaganate. Also known as Ordubaliq – “City of the Horde”

The original word is “поперечным перегородками”, which I do not know how to translate exactly.

Similar to footnote 6, this is difficult to translate. Original says “перегорожено поперечной стенкой”

Old Russian unit of measurement. One arshin = 71.12 cm / 2.33 ft

I am unsure what this refers to in the real world. Klements likely refers to this site earlier in the text

The Khitans were a semi-nomadic, semi-Sinicized people from southern Manchuria that created the Liao Dynasty in China from 916–1125 and ruled much of the Mongolian plateau

The Zungars were western Mongols, and the last independent Mongolian nomadic state. They were based in the northern regions of modern Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan

The Mongol capital

Semyon Ulyanovich Remezov, who made several maps of Siberia

Magical, thank you! Heinrich Härke's Fortress of Solitude brought the uniqueness of Por-Bazhyn to Western attention more than a decade ago, and I've loved it ever since. The ruins sit in the mind like one of Marco Polo's imaginary cities, described for the entertainment of the great Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities; and reading Dmitri Alexandrovich Klements' account here, so beautifully illustrated, adds so much depth to the story...

This was fascinating. Thank you for writing! Loved the comparison of the khanate / tang dynasty w the European powers and the Qing