The Russian Conquest of Bishkek - Military Sbornik, 1863

Translation on Russia's siege and capture of Pishpek, capital of modern Kyrgyzstan

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Hello, apologies for my hiatus from here, I felt like taking a break from Substack. I plan on returning to my regular schedule of roughly two posts a month, if not more. I also plan on branching out from long essays and translations. I will post more photo/painting collections, as well as shorter write ups on various topics. I think I will also start posting pay-walled content every month or two, which will mainly be longer translations.

Lastly, I am happy to announce that I will soon republish John F. Baddeley’s two volume work “The Rugged Flanks of the Caucasus", a long forgotten text on the Caucasus. The book is a mix between travelogue and a study of the various races of the Caucasus, with absolutely fascinating information about their customs, mythology, and more. Written by a well known English scholar and explorer of the Caucasus, this book has been long out of print and has been nearly entirely forgotten. Both volumes should be ready and available on Amazon sometime in July. Going forward I plan on republishing more of my favourite, out of print and forgotten books, so that they can see the light of day once again and be reintroduced to modern readers. And of course, I will also publish more translated books from Russia too.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation about the Russian conquest of Pishpek in 1862. Then a major fortress belonging to the Khanate of Kokand, today Pishpek is known as Bishkek and is the capital city of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan. The article is from Voenny Sbornik (Military Collection), a monthly journal published by the War Ministry of the Russian Empire. The source for this translation can be found here, under the heading “In Western Siberia.” The original text can be found here.

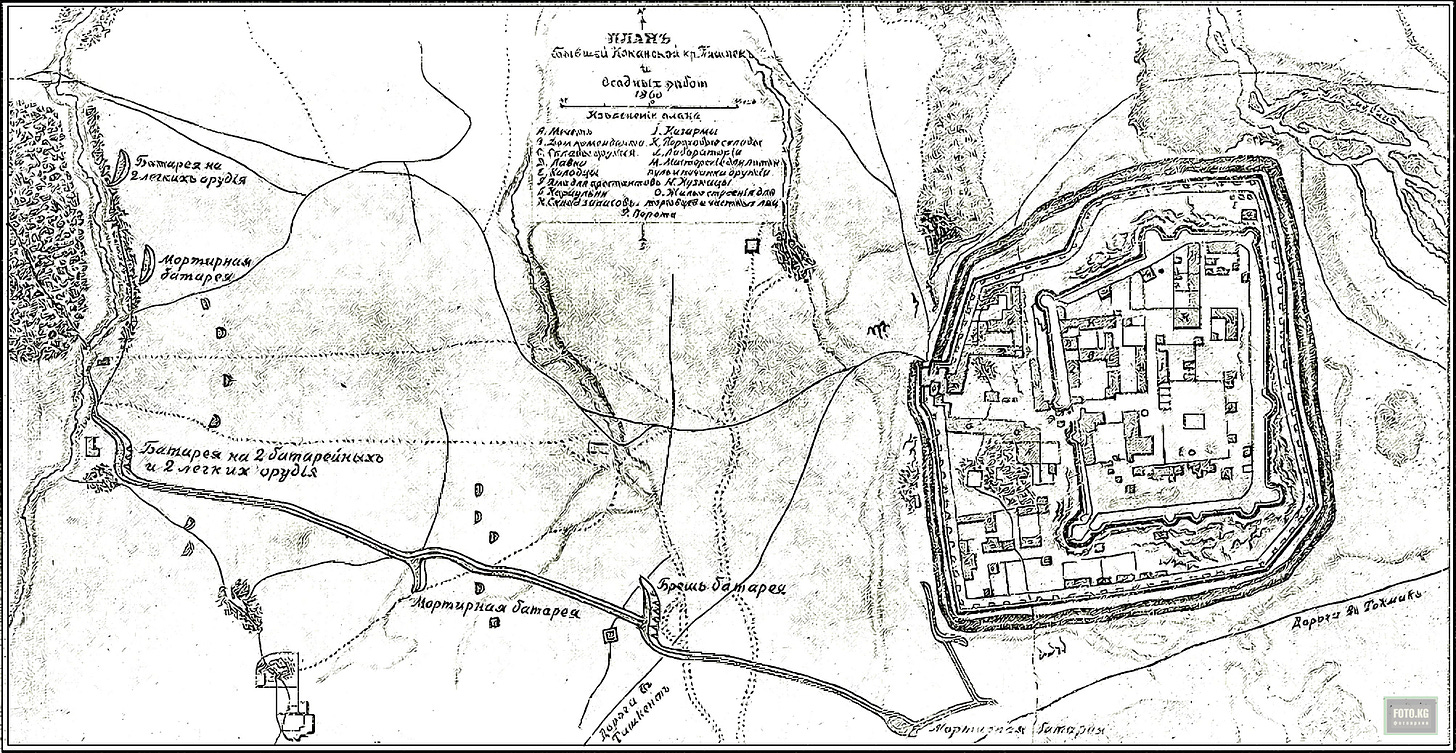

The fortress of Pishpek was founded in 1825, in order to facilitate Kokand’s control of the Chu River valley. The fortress was built on a commanding height on the left bank of the Alamüdün River, a tributary of the Chu River. It was also built along an important road frequented by caravans and nomadic cattle herders, which allowed the Kokandis in the fortress to easily control and tax all traffic that passed by. Most significant, Pishpek was located along one of the main routes between the nomadic summer and winter pastures in Semireche (“Seven Rivers” - modern day southeastern Kazakhstan) and Lake Issyk Kul. Thus, control over Pishpek gave mastery not only over the steppes north of the Tianshan Mountains, but also the routes into the mountains and trade with China.

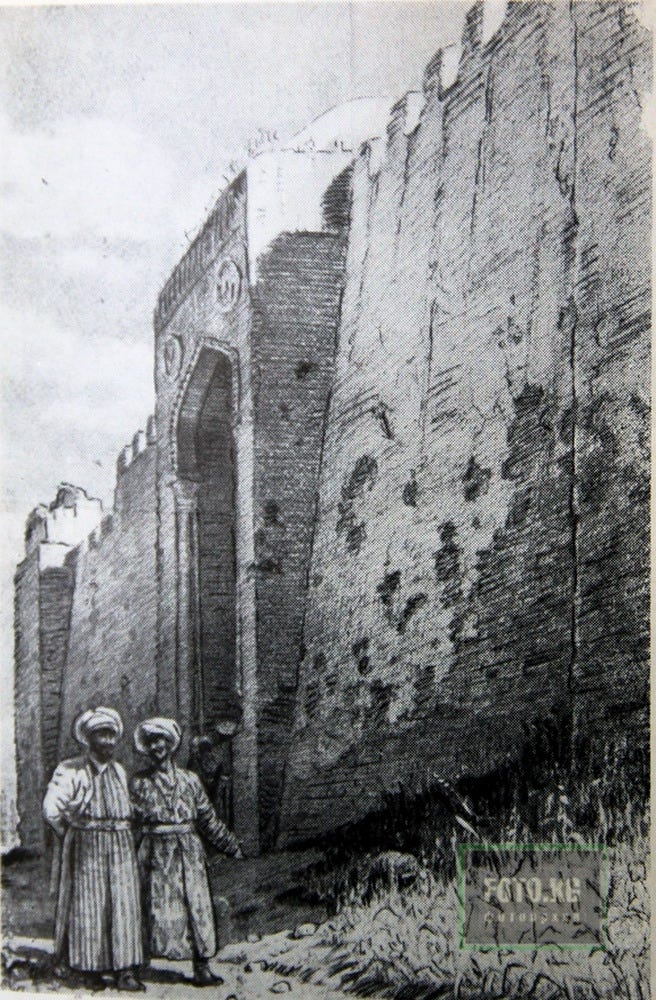

Pishpek was reportedly a standard Central Asian fortress of that era, with four walls measuring sixty and sixty five sazhens long (see footnote 8), towers on each corner, and a ditch surrounding it which could be filled with water. Along with the military garrison, the fortress was inhabited by merchants, tax collectors and the families of significant military and administrative personnel. The garrison consisted of both infantry and cavalry forces. Local Kyrgyz were obligated to supply fortress with grain.

Russian military geographer Mikhail Venyukov described the fortress as being double walled, with the outer wall measuring twelve feet high and having loopholes from which the garrison could fire from the walls. The fortress’ military supplies were stored in an earthen dugout, located in the north west corner. There were also barracks located to the north of the fortress, while to the south were shops, a square where the commander held court, as well as a pond surrounded by trees, and more barracks near the southwestern tower which were similar in appearance to sheds and housed about 120 merchants and the garrison’s officers. The citadel was located on an elevation that occupied the eastern half of the fortress. The citadel was surrounded by a three foot wall with towers. Inside the citadel were wells, vegetable gardens and fruit trees. Lastly, some of the commanders would live in a yurt within the citadel.

The 1862 siege and taking of Pishpek was not the first time Russia had captured the fortress. Once before, a Russian force under Colonel Apollon Zimmerman took the fortress in September 1860 and destroyed it. The Russians then abandoned it, allowing the Kokandis to return and rebuild the fortress in spring 1861. The 1862 conquest was preceded by a revolt of a local Kyrgyz tribe of Solto under the leadership of Baitik Kanaev. The Soltos attacked Kokandi convoys near Pishpek, but lacked artillery and were thus unable to threaten the fortress itself.

The Pishpek fortress was again destroyed following the 1862 conquest, and later a Cossack piket built there in 1864. It was expanded into a post station and later Russian colonists came and settled, as well as people from Tashkent (modern Uzbeks) and Kyrgyz. In 1878 Pishpek gained the status of a city and became the administrative center of the Pishpek uezd (district). In 1897 Russian historian Mikhail Terentev wrote that Pishkek had 752 homes. During the Soviet era Bishkek was renamed as Frunze, after the Bolshevik military commander who conquered Central Asia.

A few notes on the translation. The text consists of two parts, the first being mostly a rough summary of the second half. Due to repetition and redundancy, I chose to omit some text from the the first part since it is stated in the second part in greater detail and with better context. I chose to use the Russian word for “Kokand people”—“Kokandtsy”—as opposed to Kokandis or some other form.

For another post about Central Asian fortifications, see my translation about the Naryn.

Lastly, for more on Russian military operations in Central Asia, get my translated book, “The Expedition to Khiva” by Maksud Alikhanov-Avarsky!!!

Description of the Siege and Taking of Pishpek,1 from 13 to 24 October 1862

In the spring of 1862 forces of the Trans-Ili region conducted reconnaissance beyond the Chu River, with a detachment under the command of Colonel Kolpakovsky made up of five companies of infantry, two hundreds2 of Cossacks, four cavalry hundred, two mountain guns and four rocket platforms. The Kokand fortifications in the Chu valley included: Ak-Su, Shish-Tyube and Chaldyvar, which were abandoned by their garrison with the approach of our forces, while Merke was surrendered without a shot being fired. On the return trip the Trans-Chu detachment reconned Pishpek, which had been ruined by us during the 1860 expedition, but was later restored by the Kokandtsy.

The Kokand fortifications in the Chu valley have always served as a gathering point for enemy gangs that regular invade our territory, and therefore we could not allow their presence so close to our borders.

Moreover, the springtime reconnaissance, during which our detachment spent three days under the walls of Pishpek, might have been seen by the Kokandtsy as a failure, and thus produce an unfavourable impression of us upon them and the Trans-Chu Kyrgyz, and instill in them doubts to the power of Russia. In consideration of this, in autumn 1862 it was decided to take Pishpek again and ruin it.

…. (omitted due to repetition)

Among the efforts undertaken to study the country near our territory, it is impossible not to mention the bold actions by the general staff Leib-Guards Finland Regiment Lieutenant (currently General Staff Captain) Krasovsky, who, with a hundred of Cossacks, from the region of the Siberian Kyrgyz,3 from the river Sary-Su went across the hungry steppe to Syr-Darya to Fort Perovsky,4 establishing communication between our frontiers.

Description of the Siege and Taking of Pishpek, from 13 to 24 of October 1862.

(Excerpts from the report of the commander of the Orenburg department corps to the War Minister)

For the proposed expedition to Pishpek in autumn 1862, a detachment was formed in the fortress of Verny5 of eight companies of infantry, which including four rifle companies, and two hundreds of Cossacks, with eight guns (in two batteries) and ten mortars.

By 5th October the detachment had concentrated at Kastek with the necessary military supplies and provisions for twenty five days, and on the following day they departed towards Pishpek in two columns. The main force of the detachment with its artillery and heavy equipment went under the commander of Colonel Kolpakovsky, travelling over the Kurdaisky pass to the Kassyksky ford on the River Chu; the Cossacks with two mountain guns, under the command of General Staff Captain Protsenko6 along the Kastek gorge to the Chumisky ford. By the 13th both columns had neared Pishpek and assembled two verstas7 from its western side, on the River Alaarcha. In the same evening siege works began, which were decided to be carried out on the northern corner of the western side of the fortification. A trench was dug 250 sazhens8 from the ditch, dug at first parallel in the same place as in 1860.9

By the morning three batteries had been set up and armed: four guns were placed 210 sazhens from the fortress wall, and two mortar batteries, with five mortars each, were set up thirty sazhens closer. Communication was established between the battery and ditch. The enemy, probably not hearing our work, did not open fire; they only noticed it at dawn, and then the Kokandtsy began moving their guns from the southern corner of the fortress’ western side to the northern one.

On the 14th, at ten in the morning, indirect and aimed fire began, which the enemy responded to with one large gun that was set up on the southern tower of the citadel, and from two smaller gun, placed on the outer wall. Cannon balls from the larger gun even fell near our camp (two verstas from the fortress); but as a result of our fire this tower was bought down and the gun was silenced. During the night of the 15th, the trench of the right battery was advanced seventy two sazhens forward, and at its end a battery emplacement was set up for four guns and a protected firing point for riflemen. These works were made under enemy fire. Our side also continued its bombardment throughout the night.

The Kokandtsy repaired the damage inflicted by us during the night, and in the morning they opened powerful fire on us, both indirect and aimed, from mortars of eight and half inch caliber. By ten in the morning enemy bombs were landing in our supply depot, built together with the battery emplacement to provide a supply of daily ammunition, and blew them up. Seven lower officers were killed, one officer and three common soldiers were wounded, four officers and ten common soldiers were concussed and ten lower officers were burned. The concussed remained in their places, however. Not much damage was inflicted on the battery itself, and our guns quickly opened energetic fire.

During the following night the trench was extended another seventy sazhens, and forty two sazhens from the fortress a mortar battery was set up.

At ten in the morning, four defectors from Pishpek appeared in the camp. They said that the garrison, despite significant loses from our fire, was in good spirits and decided to defend as long as they could. The commander of the garrison was Rakhmatull, but the person in charge of its defense was Sarvaz Tyube-Kul. The Kokandtsy assumed that we could only take the fortress by storm, since they believed it to be impossible to break through the wall with our guns; as for mines, in their opinion the Russians did not have enough powder.

In fact, the garrison defended the fortress very effectively; energy, ingenuity, and some artistry was visible in everything they did. The damage inflicted by us during the day was repaired at night, new defenses were prepared, new loopholes and embrasures were made, and in response to our own work, new weapons were dragged forth: enemy rockets even appeared. Not merely that, the Kokandtsy found unprecedented decisiveness: in the morning of the 16th, when our works began nearing the northwestern corner, near where a gate is located on the northern side, the garrison made a sorties. Up to 100 soldiers ran out of the fortress, and hitting the dirt in a hallow, they began to dig a trench in order to enfilade our works; but Praporshchik10 Nikolsky with thirty four hunters rushed at the Kokandtsy with bayonets and forced them back into the fortress.

Our trench led past the northwestern corner in a zigzag pattern, directed to the middle of the western side; opposite the corner a fortification was built, covered by earthen bags with openings for fire.

On the 18th work continued further. Proximity to the enemy forced us to dig quietly. Also on this same day stutzen11 fire began. Our riflemen did not allow one person to show himself from behind the wall, and the enemy could only fire from the loopholes. The garrison placed a gun on one of the ledges of wall, but all of their efforts were in vain, since accurate fire by our riflemen did not allow anyone to come near the gun.

At ten at night, the commander of the 1st company of the 8th battalion, Lieutenant Panov, with fifteen hunters, used the darkness to successfully get into the ditch and determine its size.

On the 20th, the end of the trench was ten sazhens from the ditch, and was branched to both sides, nearly parallel to the opposing side of the fortress, and formed a semi-parallel shape, meant to serve as a jumping off point for the storming column.

Our work slowed on the last day due to our encountering of rocky soil. A few times the garrison attempted to attack our work with canister shot, as well as with bombs and rockets, but they were unsuccessful.

At this time our fire caused an explosion and fire in the fortress. It turned out that a grenade landed in their powder that was being transported from the citadel in a carriage.

Work on the trenches ended on 21st of October and on the 22nd tunneling into the ditch began. The tunnel had to run five sazhens, without any sappers: but, thanks to the energetic management by the military engineers, staff captains of the Krishtanovsky 1st and 2nd, work advanced forward quickly, and by the night of the 24th, the tunnel had reached the ditch. A covered crossing over the ditch was quickly set up, but the garrison, noticing this, opened sustained fire: grenades, rockets, stones, and sheaves of grain set on fire flew into the ditch. In the morning work was resumed, and the covered crossing was advanced forward. The ditch at this time was literally on fire from the all of the burning material that had been thrown from the walls of the fortress.

Around nine in the morning, the Feldfebel12 Masterov of the 9th linear rifle battalion rushed forward and began digging a hole in the wall.

At 11 o’clock the mine cavity was ready; all that remained was setting the mine. The explosion was supposed to be made on the same day, and the order to prepare for the storm had already been given. But at 11 o’clock a noise arose in the fortress, and from behind its walls cries of “aman” (mercy) rang out.

Fire was quickly halted, and at 12 o’clock, at the battery, Colonel Kolpakovsky accepted Tyura-Kul and the senior officer behind him who had both exited the fortress. Tyura-Kul handed him a letter sealed by the son of the dead commander Rakhmatull, which surrendered Pishpek.

Following this, the gates covered by earth were cleared by our people, and the unarmed garrison began to exit from the fortress.

In total, 764 people left the fortress, including twenty two Kokand officers and 560 soldiers (among whom were 6 runaway Russians), eighty two merchants and ninety two women with children.

Our trophies were five large copper guns on mounts (of which one was a howitzer, of the same caliber as our guns, and one mortar of a good make with a eight and a half inch caliber), four small cast iron guns, ten falconets, one large banner of Rakhmatull, some medals, a significant number of various rifles, up to 200 poods13 of powder, up to 7000 cannonballs, bombs and grenades, a part of the supplies, a significant amount of lead, bullets, and more.

Our loses consisted of thirteen dead among the lower ranks, and three ober-officers and fourteen lower ranks wounded.

Editor note (Military Sbornik): Pishpek is a rectangle, around 100 sazhens in length, with towers on its corners, is surrounded by two strong clay walls, which in the south sun dries and hardens like stone. The outer wall has a height of 2 sazhens and width of 1 sazhen; the inner citadel is similarly thick. The fortress is surrounded by a ditch that is not wide, but deep; loopholes are made in its walls, while the towers have embrasures for guns.

A military unit used by the Russian Empire. A hundred was literally made up of a hundred soldiers/riders.

This likely refers to the Kazakhs along the Irtysh River, which then were apart of the Middle Horde and today is northeastern Kazakhstan. Administratively Russia considered this region to be apart of Siberia.

Formerly known as Ak-Masjid (White Mosque), it was the first major settlement Russian captured on the Syr-Darya River, also from Kokand. Today it is known as Kyzylorda.

Modern Almaty in southeastern Kazakhstan.

I believe this is Alexander Petrovich Protsenko, 1836-1892.

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 kilometers or 3,500 feet.

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 sazhen = 2.1336 meters or 7 feet.

This was a tricky sentence to translate accurately. The original says: Траншея открыта в 250 саженях от рва из того же оврага, принятого за первую паралель, как и в 1860 году

A junior officer rank.

a type of high-caliber rifle with a short barrel.

A junior officer rank, of German origins.

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 pood = 16.38 kilograms or 36.11 pounds.

![[object Object] [object Object]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!DL9o!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8d6e005c-738b-44df-bf13-fd7c3bd2786b_726x606.png)

Excited to read The Rugged Flanks of the Caucasus when it's republished. I am just about done with The Expedition to Khiva and have really enjoyed learning about this time period in the region. I can't help but constantly think of parallels the expedition had with American efforts to reign gain control from one ocean to another across a brutal frontier. When The Rugged Flanks of the Caucasus gets republished, will you be providing an intro like the one in Expedition to Khiva? That was very well done.

Thanks for the tip, I'll try and search out Morrisons book. The rail project is of course now all tied into the China strategy of a 'silk road' to the West although the Russians still have a big hand in it.