Attack by the Kyzylayaks on the Zaisan Outpost - Ivan Babkov, 1912

Translation about an attack by Chinese insurgents on a Russian frontier post in Central Asia

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation from “Воспоминания о моей службе в Западной Сибири. 1859—1875 г. Разграничение с Западным Китаем 1869 г. — СПб., 1912. (Memoirs about my Service in Western Siberia. 1859-1875. Demarcation of the Border with Western China 1869. - Saint Petersburg., 1912.). The source for this translation can be found here. The original text can be found here (часть IV, глава V).

The author Ivan Fedorovich Babkov was born in 1827 in Saint Petersburg, and spent most of his life in the military. In 1848 he participated in the Russian intervention in Hungary which helped the Hapsburg monarchy suppress the ongoing revolution there. Later in 1872 Babkov was appointed to the position of chief of staff of the Omsk military distrust. Omsk was founded in 1716 and served as Russia’s window to the eastern Kazakh and Zungar steppes. At the time of the events described in this translation, Babkov was a Major-General and was serving as military governor and commander of forces in the Semipalatinsk region.

The translation focuses on an attack carried out by the “Kyzylayaks”, a bandit group made up of Chinese convicts who were exiled to Chinese Central Asia (today the province of Xinjiang), on a Russian frontier post in 1869. This was all made possible thanks to the lawlessness that broke out in Chinese Central Asia during the Dungan Revolt, a mass uprising by Muslims across the northwestern quarter of the Qing Dynasty from 1862 to 1877. During this period Beijing lost control over its Central Asian possessions. Numerous bandit formations arose that began raiding the Russian Empire’s newly conquered territories in Central Asia. These raids prompted Russia to temporary occupy the Ili region in 1871.

As stated below, the Kyzylayaks were primarily Chinese formation. The word itself is Turkic, a composite of “kyzyl” which means “red”, and “ayak”, which could mean either feet or legs (in Turkic languages, as in Russian, the word for feet and legs are the same, no differentiation is made). Thus the name Kyzylayaks means “Red-legs.”

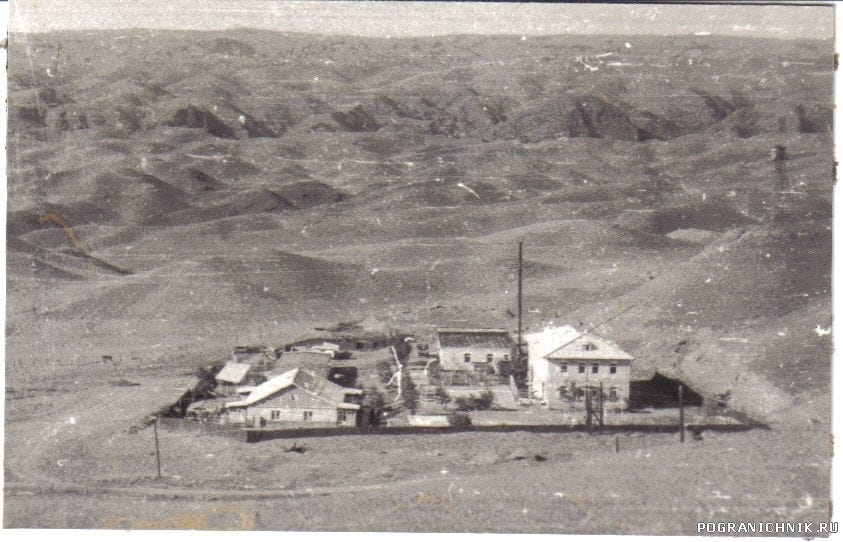

The Zaisan post was located southeast of Lake Zaisan, and about 50 kilometers from the Chinese frontier. Lake Zaisan is a large lake that separates the upper Irtysh, also known as the Black Irytsh, from the remainder of the river which flows northwards into Siberia, eventually merging with the Ob and discharging in the Kara Sea. The Russians first reached Lake Zaisan in 1719 during an expedition commanded by Ivan Mikhailovich Likharev. The purpose of Likharev’s expedition was to recon the Irtysh River, to see where it led, and to establish Russian fortresses along the river. In the course of his expedition he founded several outposts, including Pavlodar, Semipalatinsk, and Ust-Kamenogork, which formed the core of the Irtysh Line, Russia’s fortified frontier guarding southwestern Siberia and its strategic mining operations in the Altai Mountains.

The Zaisan post was founded much later in 1868, during Russia’s expansion southwards into the Kazakh Steppes and it conquest of Central Asia. The Zaisan post became the headquarters of the Zaisan pristavstvo. A pristavstvo was a territorial-administrative unit headed by a pristav, and were created by Russia to administer its Muslim populations in the Caucasus and in Central Asia.

While initially a frontier post along the Chinese border, Zaisan later became a lively trade point between Central Asians, primarily Kazakhs and Tashkentis, and Russians who settled on the Irtysh River at Pavlodar and Semipalatinsk. The Zaisan post today is simply known as Zaisan, and is located in Kazakhstan.

Lastly, it should be noted that the Kyzylayak attack on Zaisan occurred on 30th May, 1869. Thus, this event occurred almost exactly 150 years ago as of the date of this post’s publication.

Attack by the Kyzylayaks on the Zaisan Post

… The successful completion of the demarcation of the border was particularly not liked by the local frontier command, as it provided the best evidence that reports from the frontier commander concerning the rebellion and unrest in the adjacent Chinese territories were entirely inaccurate, which made it difficult to set the state border and the enforcement of article 4 according to the Treaty of Beijing.1 Despite all of the assurances of disorderliness and turmoil on the western fringes of China, myself and a handful of Cossacks traveled unhindered across the all of our border regions that are adjacent to China without encountering even one attempt by the rebellious Chinese subjects to attack us.

Meanwhile, the rebellious foreigners, known under the name kyzylayak, dared to attack the Zaisan post which was defended by a strong detachment. Yet most regrettably, before our very eyes they plundered a Kyrgyz2 aul3 under our authority, while the forward defenders of the post suffered significant causalities. This attack, according to my limited understanding, was not justified by anything, as will be explained below.

I first received intelligence on this attack from scouts while I was at the time setting up frontier markers in the Altai Mountains and had just arrived to the Chinese piket4 of Manitu-Gatul-Khan on the Black Irtysh at the end of August. This intelligence was very limited and contradictory. But upon my arrival to Kokpetka I had already completely familiarized myself with this affair down to the smallest detail. Judging by personal stories, those who are deserving of trust, and also newspaper correspondence, in particular a report based on an eyewitness account by the Cossack officer Nesterov, the affair occurred as follows.

Speaking of the Kyzylayaks, it must be first said that this name refers to a multi-tribal gang consisting primarily of convicts exiled to western China from the inner provinces, and were engaged in robberies and brigandage, which was made possible by the alarming state of affairs that had arose in the western regions of China during the time of the Dungan uprising.

The attack by the kyzykayaks on the Zaisan post occurred on the 30th of May, 1869, at 5 in the morning, and was completely unexpected. The first news of this was given to us by Kyrgyz, who had ran to the post in large crowds fleeing from the depredations of the Kyzylayaks and sought help. The appearance at such an hour of the Kyrgyz, with the Kyzylayaks pursuing them on their heels, naturally must have caused quite the commotion. The force that was stationed at the Zaisan post were mostly absent, either cutting timber in the forest 20 verstas5 away or performing other cordon work elsewhere. In general, at this post there were no precautions taken in the case of an attack by hostile Chinese insurgents. The alarm was only sounded after the Kyzylayaks, while pursuing the Kyrgyz, had broken into the post. The Zaisan pristav was then alerted, who initially did not want to believe there was an attack underway by foreign predators. The force was gathered by the alarm, consisting of 20 Cossacks and 2 under strength infantry regiments. The Cossacks turned out to be without horses, which were at the time out at pasture 12 verstas away from the post. But the Cossacks were not confused and still managed to quickly jump on the first Kyrgyz horses they came across and boldly attacked the predators that were robbing and killing our Kyrgyz near the Zaisan post. Despite the numerical superiority of the Kyzylayaks who were nearly 500 men strong, they could not hold back the rapid and brave attack by our Cossacks and were forced back from the post. During the subsequent hand to hand fighting, the Cossacks at first suffered 2 deaths and 7 injured. Meanwhile, the infantry had managed to arrive in time, forming a line and were prepared to open fire on the Kyzylayaks, but were held back by the pristav, who had the intention of entering into negotiations with the them.

Now the Cossacks, using their horses which were driven back from pasturing, started chasing the Kyzykayaks, but they fell into a swampy place and in the subsequent battle they suffered 2 deaths and 4 injured. The Cossacks then, together with infantry consisting of the two under strength brigades, sent off under the command of the pristav in order to further purse the Kyzykayaks who were already 8 verstas from the post. But the detachment, composed mainly of infantry, turned out to be unable to catch up with the quickly fleeing bandits. And therefore the pristav decided to continue the pursuit the following day with the full force of Cossacks and infantry mounted on Kyrgyz horses. But this did little to help: the Kyzylayaks were already long gone and catching up to them was impossible. And therefore, our detachment on 2nd June returned to the Zaisan post. While pursing the Kyzylayaks on 1st June, a few of our guns were captured, along with several hundred sheep as well.

The suddenness and the seemingly entirely impossible attack by the Kyzylayaks on the Zaisan post clearly showed that there were no orders prepared by the pristav to guard the post in the case of an attack by Chinese foreigners. Simply put, there was no guard at all, it did not exist. This circumstance arose from the false belief that enemies in the steppes could be treated dismissively. The commander had lost sight of the fact that in Asia there are no enemies that can be neglected, all the more so considering that information on the Kyzylayaks’ preparations for the attack was reported to the pristav two days prior to the attack. But he mistrusted this news, and as a consequence of this, apparently no precautionary measures were taken. The post’s command were not even concerned enough to set up an advanced guard of pikets and sentries. An important note that should not be forgotten is that Governor-General Khrushchov, who visited the Zaisan post two weeks before the attack had asked the Zaisan pristav the following question: how does he plan to act in the case of an attack on the post by Chinese insurgents? To this the pristav answered that he does not allow for thoughts of any sort of attack. But in the case that predators do attack, undoubtedly they will be repulsed by our forces and that in general he vouched for the security of the post.

Such were the circumstances that accompanied the attack by the Kyzylayaks on the Zaisan post, according to the information reported by the Cossack officer Nesterov. According to many accounts which I happened to hear during my stay at the frontier, all of the above information was accurate in the broad outlines. Upon my return from the Chinese border to Omsk, I, to my greatest surprise, found out from the newspapers that the military command of the Zaisan post has put out a whole series of refutations against some of the facts that were reported by Nesterov. In this refutation the affair was given a slightly different colouring. According to them, the Kyzylayaks’ advance on the Zaisan post was completely unexpected due to exceptional local circumstance. The Kyrgyz Kireev tribe, who then nomadized in the valley of the Black Irtysh, migrated to the mountains of the Altai only on the day before the movement of the Kyzylayaks. With the departure of these Kyrgyz the valley was made completely deserted. The Kyzylayaks went along this valley entirely unnoticed by anyone. According to those who objected to Nesterov’s account, not only did the darkness of night time conceal their movements, but so did the tall grass growing in the locality, which was so tall that it even concealed horse riders during daytime.

On the day of the attack, the forces at the Zaisan post were preforming cordon work and some from the lower ranks were sleeping after preforming guard duty. At dawn on the 30th of May the Kyzylayaks appeared, completely unexpected, near the auls of our Kyrgyz located near the Zaisan post, and then began to herd away their cattle. When these Kyrgyz, fleeing from this pogrom, arrived running to the Zaisan post and first reported the appearance of the Kyzylayaks, the pristav ordered the alarm to be sounded. Unfortunately, neither the pristav nor the Cossacks at the post had their horses, which were out grazing at the time, and due to this they had to take horses from the Kyrgyz. The Cossacks met the Kyzylayaks half a versta from the post and attacked them. But at their first clash, due to misfire from the Cossacks’ rifles, two Cossacks were stabbed to death with pikes. At the same time, those galloping after them turned back as 6 people were injured. With the remaining Cossacks, the pristav joined the infantry which had just arrived on foot. The pristav’s horse was wounded, and when he turned to a Cossack officer that was there and asked for his horse, the Cossack refused, and for this the Cossack was arrested. Meanwhile, the Kyzylayaks, spooked by the fire from out infantry, began to turn back. The infantry then advanced, and the pristav went on horseback. These Cossacks, according to statements made by the pristav and repeated by the commander a hundredth,6 due to the poor conditions of their rifles and the weakness of their horses they could not at this time deliver a blow to the Kyzylayaks, who were already reeling from the fire by the infantry. Due to this, the Cossacks broke from their line and were limited to firing from their flintlock rifles. During their flight, the Kyzylayaks fell into a swamp and were overtaken by the infantry. The Cossacks, according to the pristav, could not pass through the swampy area and despite all of their efforts, were not in a condition to completely defeat the Kyzylayaks. All of the cattle captured from the Kyrgyz were recovered by our forces. This circumstance is explained by the fact that the Kyzylayaks, for the sake of saving themselves, were forced to leave behind the captured cattle. If they had done otherwise, there would have been exterminated to the end.

As stated above, our Cossacks were not able to immediately mount their horses, as the Cossacks’ horses were away from the post at pasture. The pasturing land was not near the post. According to those who defended the post’s command, it was necessary to keep the Cossacks’ horses at pasture due to the lack of fodder at the start of the summer and lack of hay prepared in advance, which was not delivered to the camp.

At first, even the very surface level considerations of the objections laid out above by the military command of the Zaisan post, the conclusion cannot be avoided that they touched upon only some of the details surrounding the attack, and they do not at all explain the essence of the affair as described by Nesterov. Simply put, the main issue – the failure to take measures for guarding the post and the failure to punish the Kyzylayaks for their attack – was not was refuted. And as a consequence, it becomes an indisputable fact. Due to our foresight, that the forces at the Zaisan post turned out to be unprepared to counter hostile actions by the Chinese insurgents. Such was the lack of fighting readiness by the Zaisan forces at the time.

For example, from the 30th of May, according to the objectors, the Kyzylayaks made use of the local terrain to conceal their movements up to the Zaisan post. Due to this, their appearance was completely unexpected. This explanation serves not as a justification, but rather as an accusation against the commanders of the Zaisan post. As the particularities of the terrain in the Zaisan region and its natural conditions were beneficial to the Kyzylayaks in helping to conceal their movements, it is then clear that such a situation requires special caution in observing the frontier and taking strict measures for vigilant guard of the post and thus providing it with security from any unexpected attacks, and even more so from being taken by surprise. And thus, the Zaisan pristav should have at least done some prior thinking of what actions would be taken in the case that Chinese rebels invaded our territory for the purpose of robbing our Kyrgyz and others hostile actions. This raises the urgent necessity to create a plan in advance for such a case. Before anything else, special measures should have been taken to guard the forces and residents, those located at the post and also the surrounding nomadic population, from a sudden attack by violate and predatory Chinese foreigners. Night guards should have been place along the roads leading to the post, at a distance of approximately half a versta from it. Among these guards, sentries and concealed lookouts should have been stationed along both sides of the road to monitor side paths, in order to give no possibility to small gangs of predators and barantas7 to unexpectedly approach and break through to the inner part of the post. The guards protecting the herds, particularly at night, should have been strengthened. For checking the vigilance of the sentries and concealed lookouts, patrols should have been armed, and more than this, special officers should be sent to check on them from time to time.

Finally, it was necessary to mark in advance special assembly points within the post for infantry and Cossacks in the case of alarm, and more than this, a general assembly point at its outskirts for all garrison forces in general. If the plan is made in advance, with all circumstances thought out and foreseen, then such preparations will give confidence in the forces, encourages the spirit, and help them to steadfastly meet danger and preserve calmness and composure at such difficult times. Simply put, the commander would then have the fully prepared for all possibilities. Clearly, if all of these orders were made, constituting in essence the most elementary rules of military precaution – in regions requiring special security and guard duty, commanders and forces should be familiar with their responsibilities in advance, and the sudden attack by the Kyzylayaks should not have caused such commotion and confusion in the post. Then there would have been no such need to send the Cossacks first on a decisive attack against the Kyzylayaks during their very first encounter. Cavalry, and in particular Cossacks, as is known, are far better at finishing a attack against the enemy than compared to starting one. In the current case this all the more so should not have been done, because the Cossacks did not have their horses, trained to move orderly into battle, but instead they rode on half-wild Kyrgyz horses that were shy and not well trained. Siberian Cossacks, as I have repeatedly mentioned, possessing the particular ability to adapt to the terrain and circumstances, in my view acted properly by dispersing from a line which gave them full possibilities to observe the enemy, while at the same time covering the infantry. Had the Cossacks not rushed to attack the Kyzylayaks at the very first stage of the battle, if instead had the pristav ordered the Cossacks to build a small barricade,8 and then retreated while firing back, they could then have lured the Chinese to our infantry, which at the time were already lined up in military order. The Cossacks could then have quickly dispersed in front of the infantry, giving them the possibility to carry out a few consecutive volleys. The fire from our infantry at close range would have immediately curbed the warlike fervor of the Kyzylayaks and would inevitably have forced them to retreat. At this moment the pristav should have taken advantage of the situation, and only then let the Cossacks finish the Kyzylayaks off and then to persistently pursue them.

Such an order, considering the Cossacks abilities for similar types of actions, would have in this case been more appropriate and intelligent. If that had been so, the regrettable episode would not have occurred, where the Cossacks were thrown back by the enemy into an infantry line and the pristav remained without a horse after having received a refusal from the nearby Cossack officer to give him his horse, and was thus forced to search for a horse at the most critical of moments. This circumstance serves as a clear demonstration to the degree of authority that the pristav had among his subordinate officers.

But most of all it was regrettable that the Kyrgyz of the Zaisan region, who were transferred along with their lands from being Chinese to Russian subjects as according the Peking Treaty, were then looted twice by Chinese foreigners soon after becoming Russian subjects: in 1867 by Kalmyks9 led by Chogan-Kegen, and in 1869 by the Kyzylayaks. Understandably, these pogroms did much to shake the trust that our new subjects had for Russian authority. Another regrettable fact in this affair was that the Kyzylayaks, having slipped away from us, were later caught in the valley of the Black Irtysh at Bulun-Tokhoi by the Kalmyks under Chogan-Kegen and in the end were defeated and scattered. Thus, the Chinese, despite all of their weakness and powerlessness in the western region of their empire during the Dungun rebellion, when there were nearly no traces of their power, were nevertheless able to deal with the Kyzylayaks, while we, despite the relatively strong detachment stationed at the Zaisan post, were not only incapable of completely defeating the Kyzylayaks, but suffered 15 causalities, with 11 Cossacks wounded and 4 dead, at the initial clash with them. This all serves as clear evidence that the Cossacks were the main fighters in this affair, as from among all of the forces at the Zaisan garrison only they suffered such significant causalities. Meanwhile, the Zaisan command mainly blamed the Cossacks for failing to punish the Kyzylayaks for their raid. According to the command, if the Kyzylayaks were able to quickly flee from the Zaisan post and successfully conceal themselves from our pursuit, this happened because the Cossacks were poorly armed and had weak horses that could not catch up with them, despite the efforts made by the pristav. But if the Cossacks did not have weapons that were good and strong, and lacked hardy horses capable of moving quickly for long periods of time, then this failure should be better attributed to the command and not to the Cossacks themselves, who did everything that was possible of them to do. It must never be forgotten that the Siberian Cossacks were at this time, as we can see, our advance forces in the steppes of Middle Asia. And no one said a kind word about those people, fallen in an unequal battle defending the Zaisan post with their chests. The feeling of justice alone requires not blame, but rather praise for our brave Cossacks, who fell on this ill-fated day due to the fault and mismanagement of a stranger.

More on the Kyzylayaks (added by Rus_turk):

Russia’s presence at Zaisan dates back to 1868. In this year Russian forces arrived here – a battalion of infantry and two hundreds of Cossacks. Soon, parts of this force came under attack by criminal Chinese exiles – the Kyzylayaks (red legs) – from the city of Bulun-Togoi, on the frontier with Zaisan. The Kyzylayaks, numbering up to 800 people, were armed with spears, flintlock rifles, and more. These criminals robbed Kyrgyz subject to Russia and with this purpose they made an attempted attack on Zaisan. The attackers were fought off with great losses for themselves. (B. Gerasimov. Trip to Southern Altai. // Notes of the Semipalatinsk Russian Geographic Society. Volume 16. 1927.).

This article states that both Russian and Chinese frontier forces must provide assistance to merchants and others

These are actually Kazakhs. Up until the Soviet period, Russians called the Kazakhs Kyrgyz. The Tianshan Kyrgyz were known as Kara-Kyrgyz, Dikokamenny Kyrgyz (Wild-stone) or as Buruts, after a leading local tribe

An aul is a Turkic word for village, but as they were nomads this was probably more like an encampment

A small outpost

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 km / 3,500 ft

Cossack unit

“Baranta” is the word used by nomads for cattle rustling

The original word is “лава,” from “лавка,” which is a bench of sorts. I doubt Babkov means a literal bench, so I assume what he actually means is some sort of defensive structure most similar to a bench, which I think would be a small barricade

Kalmyks were a Mongolian people. These in particular were likely western Mongols that were serving the Qing Dynasty and turned to banditry during the choas of the Dungan revolt

I really appreciate this translations of documents that we would never have any scope to see in English. They are a fascinating window to a different time and place, one most Anglos are not familiar with.

It’s like the Wild West