The Expedition of I. D. Bukholts and the Founding of the Omsk Fortress - Evgeny Evseev, 1974

Translation of a historical essay on Russia's first attempt to conquer Central Asia and the creation of the south Siberian frontier under Peter the Great

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of a historical research essay on the founding of the city of Omsk and Russia’s earliest attempt to penetrate into the distant and unknown lands of Central Asia, authored by the local historian of Omsk, Evgeny Nikolaevich Evseev. The essay details the failed expedition of Ivan Dmitrievich Bukholts to reach the golden sands of Yarkent from 1715 to 1716, which occurred under the energetic imperialistic reign of Peter I, the Great. Despite the mission’s failure, the expedition ultimately resulted in the establishment of the city of Omsk, which became the center of the Irtysh Fortified Line defending south Siberia from nomadic raids, and later became one of Russia’s main bases from where it launched its more successful conquest of Central Asia in the mid-19th century.

Evgeny Nikolaevich Evseev was born in Omsk, in 1927, a descendant of Siberian Cossacks and other state servants who colonized the south Siberian frontier. Evseev was 14 at the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War, and initially served as an assistant to a cinema projectionist, and later joined the Red Army at age 17 as a signalman, serving on the Baltic Front and participating in the conquest of Kaliningrad. Demobilized in 1951, Evseev enrolled in the Moscow State Historical-Archive Institute, graduating in 1960, and later worked at the Omsk State Archives as a researcher. According his biography, he was not a member of the Communist Party, an organ who’s membership in was often a necessary for career advancement. He later dropped out of graduate school as a consequence of not being a CPSU member. In other words, Evseev was not a careerist. As an expert of archival materials and the urban histories of south Siberia, he published numerous historical texts and was regularly consulted by other researchers. Evgeny Nikolaevich past away in 2013. Evseev’s website, with his biographical information and many of this publications can be found here.

This essay is extremely interesting as it details an episode in Russia’s imperial expansion that nearly entirely unknown in the English language world, and sheds light on the history of relations between Russia and the nomads, as well as Sino-Russian relations.

The expedition was initiated by the then governor of Siberia, Matvey Petrovich Gagarin, who told Tsar Peter I that the city of Yarkent was rich with golden sand that lay waiting to be seized. Yet, the expedition had wider goals as well, namely the exploration of lands that lay south beyond the forests of Siberia and the established of trading ties with China, India, and the various Central Asian states.

The expedition can also be seen as a part of Peter the Great’s efforts to transform Russia into one of the leading European powers. Moscow had long viewed itself as the successor the Byzantine and Roman Empires, with the same ideology of an universal imperium, but lacked to means to carry out its grand designs. Under Peter, Russia was finally able to realize these goals. Peter’s reforms modernized Russia in the image of Europe’s leading states, and with superior technology and organization, the Russian state was able to rapidly expand outwards in every direction with explosive energy.

As Evseev points out, the Bukholts expedition was merely one venture among many similar ones that were undertaken during Peter’s reign. While Bukholts was dispatched to invade Central Asia from the northeast, Prince Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky was sent to invade the region from the northwest in 1716. Cherkassy’s first target was Khiva, located in the delta of the Syr-Darya just south of the Aral Sea. The Russian force was soon worn down by extreme climatic conditions and was constantly harassed by the region’s nomads. In the end, Cherkassy’s expedition was destroyed, and Cherkassy himself was dragged in front of the Khan of Khiva and beheaded.

While Peter’s plans to conquer Central Asia came to naught, his other ventures were more successful. The Baltic coastline was taken from Sweden and Saint Petersburg was built, “Russia’s window to Europe”. Before that, Peter had seized a foothold on the Sea of Azov from the Ottoman Empire, which brought Russian power to the Black Sea, a project that would be later completed under Catherine the Great. Peter later captured Dagestan and the “Caspian Gates” during the 1722-23 Russo-Persian War, which brought Russia to the frontiers of Persia and the Middle East. In the Far East, Russia negotiated the Treaty of Kyakhta with China’s Qing Dynasty, which established commercial relations between the two powers. Much of the tea and other Chinese goods imported to Europe at the time came from Russia’s overland trade with China, rivaling Britain’s maritime trade. Russia also first learned of Japan during this time. A Japanese merchant clerk named Dembei washed shore on Kamchatka, and was later taken to Petersburg where he informed the Tsar’s court about the existence of Japan, and even teaching Japanese language to interested Russians.

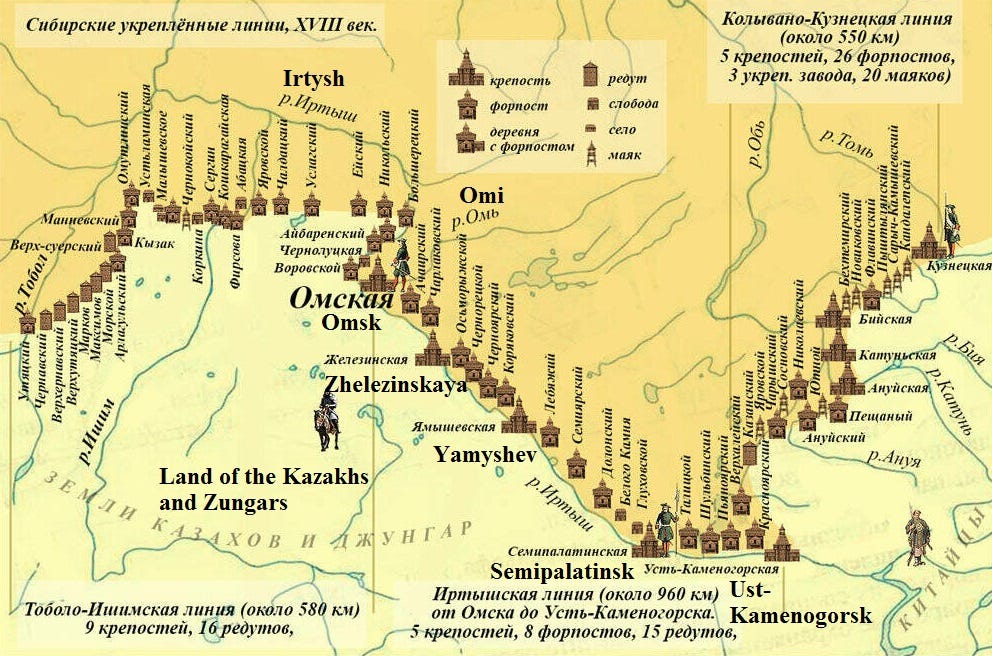

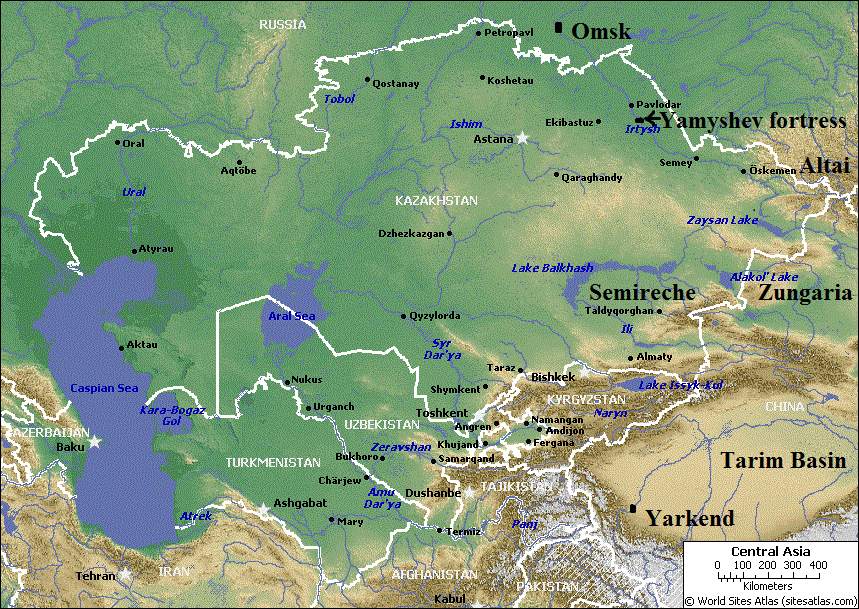

The Bukholts’ expedition was not entirely unsuccessful though. As this essay details, Bukholt’s withdrawal back into Siberia led to the founding the Omsk. Located on the River Irtysh, where the forests of Siberia meet the grasslands of the steppe, Omsk would go on become a most important Russian settlement in southern Siberia. In the years shortly after the Bukholts expedition, Russians would found further fortresses additional fortresses along the Irtysh. These include, Zhelezinskaya in 1717 (modern Zhelezinka), Semipalatinsk in 1718 (modern Semey), Ust-Kamenogorsk in 1719, and the Yamyshev fortress was rebuilt later in 1716. Omsk, along these four fortresses, became the core what would become the Irtysh Fortified Line. This line was one of many fortified lines that Russia built throughout its history. Their purpose was to extend Russian power into the steppe, to create fortified borders that would stop nomadic raiding, to limit nomadic mobility and force them to sedentarize, and to serve as nodes from where Russian authority could be exerted over the nomads. See my review of Alexander Morrison’s “The Russian Conquest of Central Asia”, section “The Russian Limes”, for a more detailed explanation on this topic.

In 1764 under Catherine the Great’s reforms, the Cossacks on the Irtysh Line were reorganized into the Siberian Cossacks force. Later in the 19th century, it would be these Siberian Cossacks who spearheaded Russia’s conquest of Central Asia. With an additional century of military modernization and Siberia better developed with improved supply bases, Russia was able succeed where Bukholts and Cherkassy had failed. Settlers from the Irtysh and elsewhere in Siberia established the fortress of Verny (modern Almaty), and led the colonization of the Semireche region, before they pressed on to Tashkent, Samarkand, Fergana, and Khiva. Thus we can say Bukholts’ failed expedition not only laid the foundation of Omsk, but also the foundation of Russia’s empire in Central Asia.

A few notes on the essay’s historiography.

Upon returning from his failed expedition, Bukholts was punished with demotion and sent to command the strategically irrelevant Narva fortress. During his interrogation, Bukholts blamed the expedition’s failure on the lack of preparation, which had been the preview of the Matvey Petrovich Gagarin, and on the existence of the active and aggressive Zungar Mongolian state which prevented the expedition from advancing. Evseev very clearly sides with Bukholts over Gagarin, an assessment that the translator agrees with. First, it is worth noting that Gagarin was later executed for corruption in 1721.

Secondly, it would have been simply impossible for Bukholts to lead his merger force of less than 3000 men to Yarkent. Not only were the Kazakhs wild and outside of Russian control, but the Zungars controlled both the Irtysh and the Tarim Basin, and were militantly opposed to Russian expansion into their lands. Even without the hostile nomads, it is doubtful that Bukholts could have succeeded. Simply the distance and terrain alone that the expedition would have needed to cross made the mission impossible. From the Yamyshev fortress, the furtherest point Bukholts reached, his expedition would have needed to travel another 1500 kilometers, or 930 miles, as the birds fly. After crossing the steppelands, the expedition would to have needed to cross the towering Tianshan Mountains. After that, they would needed to cross the Tarim Basin, a barren desert wasteland, before reaching Yarkent itself.

The expedition’s impossibility for geographic reasons alone indicates just how little the Russian state knew about Central Asia and its geography at the time. The Russians did not even know where sailing up the Irtysh would lead them. Bukholts’ failed expedition was followed by an other expedition in 1720 led by Ivan Mikhailovich Likharev. Likharev enjoyed a more friendly reception by the Zungars, and was allowed to sail up the Irtysh to its source. To the Russians’ dismay, the Irtysh flows south, past the Altai Mountains, only to turn east towards the Mongolian plateau after Lake Zaisan. Seemingly, the Russians had initially believed the Irtysh flowed south towards Central Asia and Yarkent.

Also, it is important to keep in mind that this was essay was written during the Soviet period. Certain phases and pieces of analysis are clearly products of the era’s ideological environment. These include references to the Kazakhs khans as “feudal lords”, and the statement: “suppression of anti-feudal actions within the country which arose as a result of increased exploitation of workers by the feudal state.”

Also, the depiction of relations between the Kazakhs, Zungars and the Qing Dynasty are very much colored by the ideological climate of the Soviet Union in the 1970’s. The history of the Kazakhs and their inclusion into the Russian Empire has always been a politically sensitive topic. Both Soviet and contemporary Russian historians usually portray this history as peaceful, with the Kazakhs voluntarily joinning Russian Empire. The word typically used to describe this process, “соединение” implies a peaceful joining of two peoples. This characterization is not entirely untrue, but also not wholly true either.

And as the Kazakhs were a Soviet people, Evseev depicts the Zungars as predatory and aggressive. In other words, the Russians and Kazakhs are portrayed as natural allies against the imperialist and militaristic Zungars. The actual history is also of course more complicated.

While the Kazakhs are depicted as victims of the predatory Zungars, the Zungars in turn as seen as victims of Qing (Chinese) aggression and imperialism. This is because the text was written in 1974, during the midst of the Sino-Soviet Split, where the Soviet Union was at the cusp of war with China as much as it was with NATO. Only a few years prior, the USSR and PRC had fought a significant border conflict in the Far East, for control of Zhenbao/Damansky Island, in the Ussuri River. Thus, Eseev’s depiction of the Qing Dynasty can be seen as a reflection of the political atmosphere that existed at the time.

The way Evseev frames the era’s international relations is largely influenced by the politically correct mores of the author’s era. Again, Eseev’s characterizations are not entirely wrong, “a broken clock is right twice a day”, but they are products of his era’s party line rather than objective characterizations. Though of course, any historical text will be a reflection of the intellectual climate that the author lives in, so Evseev can hardly be faulted for any of this, but keeping such biases in mind is important.

I have included all the original citations untranslated in Russian. I have also added my own footnotes in English explaining certain things that are important and relevant, but likely not known by most readers. The source for this translation can be found here.

And lastly, the 2019 Russian film “Тобол” (Tobol) depicts the Bukholts’ expedition. I have not seen this movie, so I cannot comment on its quality, but it is probably interesting.

The Expedition of I. D. Bukholts and the Founding of the Omsk Fortress

The goal of this essay, based on the available literature1 and new data discovered by us in the central and local archives, is to help correct some information that has existed since the time of G. F. Miller2 about the organization and strength of the expedition by I. D. Bulgots, about Russian-Zungar relations at the time of the expedition and about the dating of the foundation of the Omsk fortress.

At the beginning of the stormy event of the 18th century in Siberia, the process of discovering and opening up new lands continued. From 1710 – 1716 at Tobolsk various sea naval and land expeditions to the Artic Ocean, to the Far East and to Central Asia were being continuously being formed. The voevoda3 of Yakutsk D. A. Traukhnikht was entrusted with the examination and study of the Yakutsk region, colonel Ya. A. Elchin – organized the so-called “Great Kamchatka Trope”,4 Lieutenant Colonel I. D. Bukholts – expedition to Little Bukhara. For the financial-economic and national interests of the state it was necessary to study the territory of the country, carry out scientific examinations, and acquire more accurate cartographical material. From there, they searched for “unexplained peoples”, “unknown lands”, surveyed their geographic and geological relations, constructed fortresses, ostrogs5 and established trade connections with “foreign peoples.”

The leaders of the expeditions were told to “observe real state interests”, under which meant the practical needs of the absolutist empire. A characteristic feature of these expeditions was that they weaved scientific-research tasks with social-economic ones. In period of the Northern (Russian-Swedish) War6 the empire was especially in acute need of sources to replenish the state treasury for carrying out an active foreign policy, suppression of anti-feudal actions within the country which arose as a result of increased exploitation of workers by the feudal state. Such was the situation that gave birth to the idea by Siberian gubernator Prince M. P. Gagarin to launch a campaign to Yarkent for “golden sand” and to construct fortresses along the Irtysh.

Peter I, who devoted much attention to the question of searching for gold deposits in south Siberia and also to the development of trading ties with outlying Asian countries, relying entirely on such an experienced administrator as Gagarin, signed the ukaz7 authorizing the Yarkent campaign on 22 May, 1714.8 On the same day, while the Russian fleet was stationed in the Gulf of Finland, I. D. Bugolts was called to the Admiralty galley and was named commander of the expedition. Included in the expedition were master miners with exploration instruments and a detachment with canons to guard them.9 The initiator of the campaign Gagarin was entrusted with the higher leadership of the expedition and to providing it with all of its needs. Peter I, personally instructed Bukholts and offered him to take experienced Swedes, “which are skillful in engineering and mineral knowledge.”10

Who was this I. D. Bugolts and why was he entrusted with the leadership of the expedition? In pre-revolutionary Russian and Soviet historical literature, encyclopedic and reference publications, the founder of the city of Omsk went by the family name Bukhgolts (Бухгольц). However this is not true, his family was distorted. It was written differently: Bukhgolts, Bukhalt, Bukholtsev (Бухгольц, Бухалт, Бухольцев). The first to return attention to the incorrect spelling of his family name was the doctor of geographic sciences, D. N. Fialkov.11 However, he incorrectly read the family name from a service form inspection list of a Yakutsk regiment and based his assumption off of the date of birth. We identified authentic documents in the Central State archive of ancient acts with signatures stating that the family name was not Bukhol’ts (Бухольц), as believed by Fialkov, but Bukholts (Бухолц). Particularly, in one of the messages by Bukholts he says: “…your servant Ivan Bukholts beats his forehead…” and states that he signed a report on his activities”… by his hand… and sent it to Saint Petersburg to the most illustrious Governing Senate from the newly constructed fortress from the Ust-omi-river”.12 The Cherepanov Chronicle13 gives the same spelling.

I. D. Bukholts came from a Russian noble family, a genealogy which has not been studied yet. In the materials of the local prikaz14 and the Patrimonial Collegium, which managed services for the nobility, had information clarifying the pedigree of I. D. Bukholts. However, in the books of the haroldmaster’s office15 different family names are mentioned, such as Bukholtsov, Bukholtsevy, Bukholtsevykh, Bukholtov.16 An uncritical use of these materials can lead to mistakes. He was born in the year 1672. As his brothers, he was 17 year old youth in 1689 when he joined the military service. I. D. Bukholts stood at the origins of the formation of the regular Russian army,17 beginning his journey from the “fun” regiments of Peter.18 As many of the “chicks in Peter’s nest”, he passed through military science to the Life-Guard Preobrazhensky Regiment,19 participating in battles and campaigns. The older brother, Ivan Avraam Dmitrievich Bukholts, also served in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, where at the rank of colonel he was named as commander of the Shlisselburg fortress20 in 1715.21 The Bukholts brothers were well known to Peter I. It can be seen from this, that they bypassed the Military Collegium and had direct contact with Cabinet. All this, undoubtedly, determined the choice by Peter I to name Lieutenant I. D. Bukholts to lead the expedition “for Yarkent gold”.

At the beginning of June 1714 Bukholts with a group of soldiers and sergeants of the Preobrazhensky regiment departed to Moscow, where they were joined by 7 officers. Among them was his assistant, Major I. L. Velyaminov-Zernov, who later became the commandant of the Omsk fortress, and artillery lieutenant Kalander, under whose command the defensive fortifications of the Yamyshev and Omsk fortresses were built. With this team of 20 members, that constituted the main backbone of the future detachment, Bukholts headed to Tobolsk22 to form the regiment. In his letter to Peter I’s cabinet-secretary A. V. Makarov, he reports that he arrived to Tobolsk on 13th Novemeber, 1714, lived there without his team for 8 months, and then accepted dragoons23 and soldiers: “… of such, did not know anything about exercises, could not shot, are armed with unusable guns, and have not been in an armed force before”.24

There were no regular army units in Siberia: for 7 months preparations for the expedition continued: recruitment, formation, training and equipping of regiments. According the ukaz by Gagarin,25 commandants of towns in Siberia were told to send blacksmiths, machinists26 and wood workers to Tobolsk for the expedition.27 In his reports to Petersburg, Bukholts constantly expressed that the Siberian administration’s actions in preparation for the expedition were insufficient. The force was absolutely unable to responsibly carry its tasks. “They know nothing of exercises, - wrote Bukholts, - this winter and spring I received ammunition and made the guns, drilled the soldiers…”.28

By the summer of 1715 three regiments were formed: Saint Peterburgsky, Mosckovsky and Dragoonsky; by the 30th of June the detachments had 32 small river boats and 27 large ones29 and finally they set out on the expedition. Heading out with the detachment were merchants sailing in 12 small river boats and travelling in caravan with commercial goods. They reached Tara30 on the 24th of July. Here Bukholts received reinforcements – 1500 horses for the dragoon regiment, and recruits from the Tara uezd31 that were completely untrained in military affairs. “And in all, Sir, - Bukholts reported. – there are 2795 people of all ranks with my force”.32 From there, Bukholts traveled with 60 ships and with no more than 3000.33

On the 1st of October he arrived to the Yamyshev lake; on 29th of October they laid down the foundations of the fortress, and by the 10th of November the fortress was mostly ready. At the fortress an artillery ostrog was built and a barracks, around which they placed stakes as obstacles.34

On the 29th of December, 1715, Bukholts wrote to A. V. Makarov that he sent the Khong Tayiji35 news about the construction of the Yamyshev town, “so that he would be at peace with the forces of Tsar’s Majesty”. Further he reported, that going to Yarkent is impossible, because the Khong Tayiji has a force of 60,000, and with him only remained 2536 people.

Already in the period of construction of the Yamyshev fortress Bukholts understood that his force, which he had, could not fulfill the task assigned to it. The soldiers were uninterested in the campaign. They wintered at Yamyshev. At the beginning of 1716 more than 260 people ran away from the detachment. Desertion increased. Bukholts wrote to the Tsar about this and requested reinforcements: “… I must have ober- and unter-officers, and but not one sergeant nor corporal… all the people are new and have not been put to work”.36 Peter I, located in Holland and monitoring the course of the expedition, sent Gagarin an ukaz, ordering him to personally travel down to Bukholts and take measures to continue the campaign.37 But it was already too late.

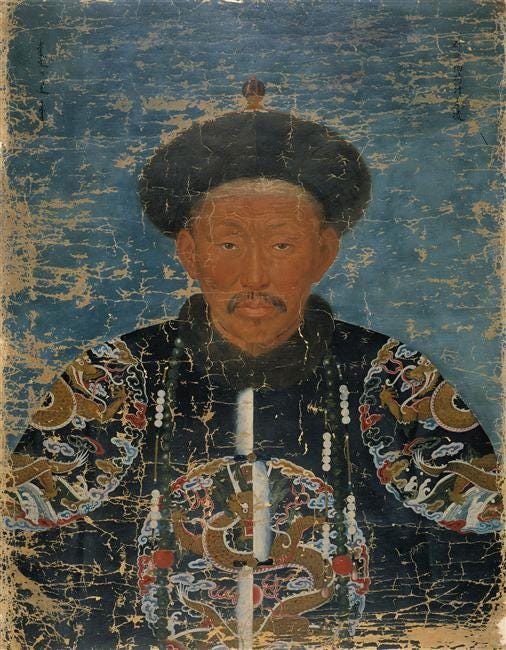

The ruler of the Zungars Tsevan-Rabdan, alarmed by the rumors about a Russian force campaigning to capture Yarkent, which he had conquered previously, sent his representative to Bukholts to discover what his orders were and what goal was the fortress built for. He regarded this as the independent actions by Gagarin, not sanctioned by the ruler of Russia. Bukholts sent lieutenant Trubnikov to Tsevan-Rabdan with a letter, in which stated, the expedition did not pursue the goal of conquering the Zungars and the fortress was built in connection with the search for ore deposits. But the Trubnikov mission was not destined to come to fruition. On the road to the Khan’s camp, he together with a convoy of 50 dragoons were taken prisoner by the Kazakhs, who were in a state of war with Zungars at the time.38 Without receiving a response, Tsevan-Rabdan moved a force of 10,000 under the command of his brother Tseren-Dondob against the Yamyshev fortress. During the night of 9th February 1716, the Zungars, having removed the Russian guards and driven away all the horse, went to storm the fortress. They succeeded in capturing part of the detachment’s food supplies. However, after the unsuccessful attempt to take the fortress, Tseren-Dondob sent an ultimatum to Bukholts demanding he leave the fortress, promising that they would be allowed to withdrawal. In the opposing case, he planned to continue the siege. Bukholts responded to Tseren-Dondob, that not only would be not surrender the fortress, but more would be built along the Irtysh as according to the Tsar’s ukaz and that friendship and trade would increase with those neighboring these fortresses. Meanwhile, the Zungars insisted that he refrain from further campaigns and abandoned areas already conquered. Having decided to hold the defenses until reinforcements arrived, Bukholts sent messengers to Tobolsk. But they were seized by the Zungars. They also captured a caravan carrying food supplies that was heading to Bukholts from Tara and Tomsk.39

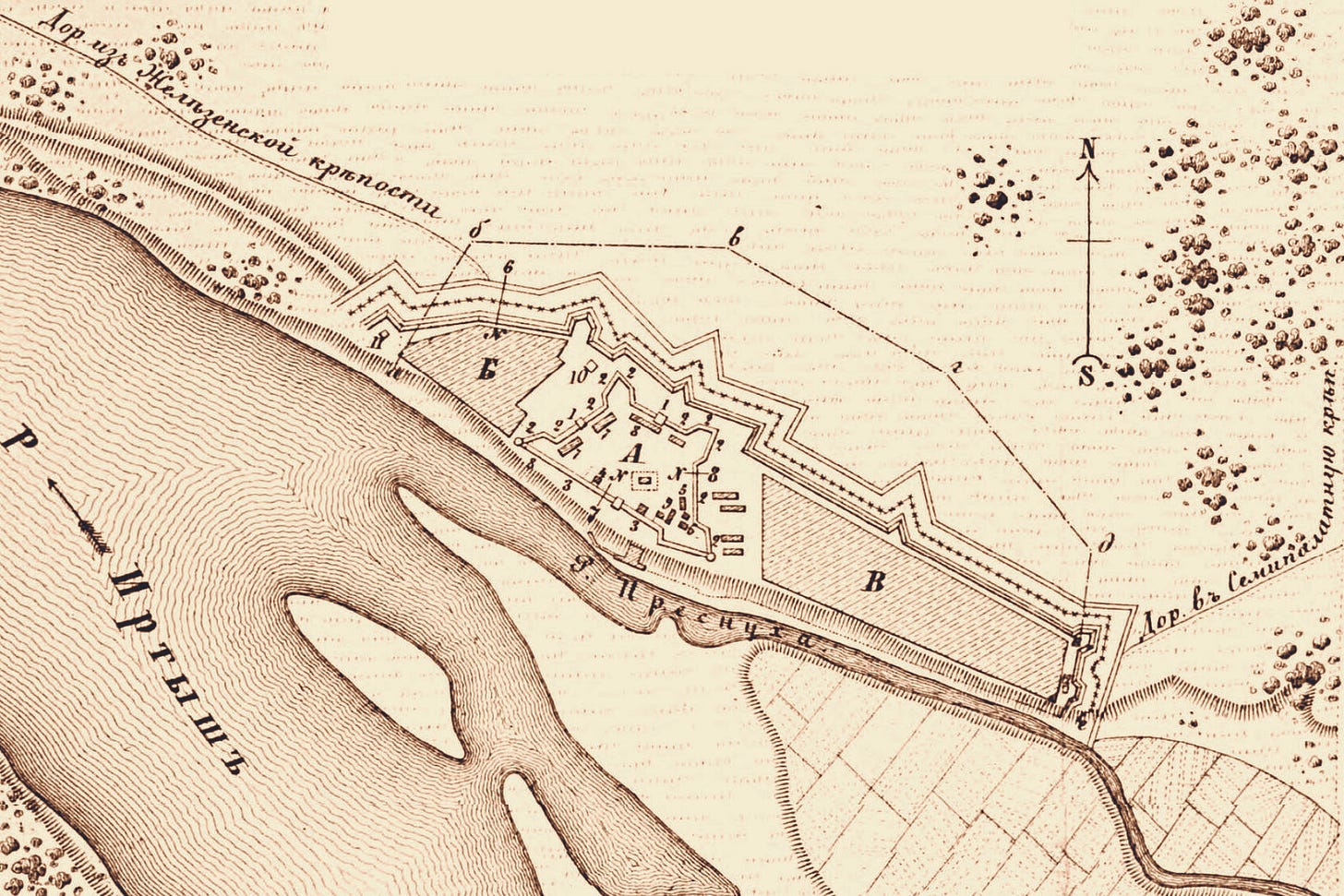

Three months went by under siege… In spring an epidemic of anthrax40 broke out, killing 20-30 people a day. There was no doctor or pharmacist in the detachment. Once the Irtysh was cleaned of ice, the military council accepted the decision to leave the fortress, as help in the near future was not expected: on the 28th of April with the remaining garrison, consisting of around 700 people, on 16 small river ships Bukholts sailed down the Irtysh.41 Around the 4th & 5th of May in the old style42 (15-16 May) the detachment arrived to the mouth of the Omi, where they constructed a fortified military camp. Bukholts, of course, knew about Russian intentions of the beginning of the 18th century43 to establish fortresses here and immediately understood the strategic value of this point as node for all possible undertakings with, and defense against, the nomads of south-western Siberia, and also for further economic development of the steppe region. Sending a report to Gagarin on the need for reinforcements, he asked for permission to establish the Omsk fortress. Soon an ukaz and 1300 reinforcements were received. Construction on the fortress began. The commander of the construction was lieutenant Kalander. The old Omsk fortress was built on the territory currently occupied by the oblast library and the park between the streets 10 years of October and Lermontovskaya. The fortress consisted of low rampart in the shape of a regular pentagon, enclosed by a palisade with bastions at each corner. Outside, fortress was bordered by a deep ditch, along which were cheval de fries44.45 By the autumn the foundational work on the fortress was completed and it was named Omsk after the river Omi. Gagarin reported to Peter I: “The Omsk fortress… is populated, great sovereign, by a large number of people”.46

The expedition of Bukholts caused complication in Russian-Zungar relations. However, the international position of the Zungars did allow them to violate peaceful relations with Russia. The Zungars were at war with the Manchurian Qing Dynasty and the Kazakh feudal lords. Wishing to enlist Russia in their struggle for the liberation of Kazakhstan from Zungar rule, a Kazakh envoy arrived to Tobolsk on 11th September 1716, who brought with him lieutenant Trubnikov, who had earlier been sent by Bukholts on a mission to Tsevan-Rabdan. The envoy expressed the desire by the Kazakhs to live in peace with Russia and their readiness to fight against the Zungars.47 The Kazakhs began the struggle for the liberation of Semireche48 from Zungar domination. Under the current situation, the fortress on the Omi became the main strong point for the implementation of the plans for the further development of the Upper Irtysh region. In his report to Peter I, Gagarin mentioned the Kazakh envoy and asked for the campaign to resume, and for a letter to be sent to the Zungar khan. On the 18th of December 1716, Peter I sent the Zungar ruler a letter, in which he spoke about his order to carry out a search along the Irtysh, up to Lake Zaisan and the top of the Irtysh, for silver, copper and gold deposits, and for this it, was necessary to build a town. The khan was requested not to create obstacles to the geological search, construction of towns and to allow nomads to nomadize in Russian lands. Peter I also promised him to protect him from his enemy49.50

To find out the circumstance of the unsuccessful campaign, Bukholts was first called to Tobolsk, and then ordered to Petersburg by an ukaz. Having handed over command of the garrison to his assistant, major I. L. Velyaminov-Zernov, he left Omsk on 22nd of December, 1716.51

In January 1719, testifying to the governing Senate about the results of the expedition, Bukholts spoke about the threat of Zungar raids… “to the mouth of the Omsk fortress” and specified the necessity to fortify it, and also to construct new fortresses higher up along the Irtysh. “… Raids and their approaches to it are frequent and many villages are ruined and they take state people52 into captivity and cattle are driven away, and their approaches are impossible to defend against, perhaps in current places that are strong committing some people and artillery will satisfy them for their defense”53.54

Although his explanation was found satisfactory, the commander of the new expedition to the upper reaches of the Irtysh, Guard Major Likharev, along with collecting materials for investigation on Gagarin’s work, he was also entrusted to uncover facts on the ground for what caused the fall of the Yamyshev fortress. While in Omsk, Likharev spoke with participants in the campaign, but the investigation did not bring any accusations against Bukholts of any kind.55

Although Gagarin had accused Bukholts of this, that he had supposedly started a fight with the Zungars, the investigation established that the expedition suffered defeated as a result of poor preparation, of which Gagarin was to a large degree guilty for as preparations were his responsibility. The Military Collegium noted that Bukholts “did to the best he could”. The complex international situation in the East, necessitated the arrangement of the Russian-Chinese frontier prompted Peter 1 in 1724 to against send Bukholts to Siberia. The Siberian gubernator, Prince Cherkassy, was ordered to allocate to Bukholts a force of 1000 cavalry and 1000 infantry from garrison regiments.56 In 1726 he, together with the Russian envoy S. V. Raguzinsky traveled to China. To Bukholts the managements of the frontier regions with China was entrusted, with the right to carry out changed and reforms, as he found necessary. Colonel Bukholts zealously commenced his work. He built a new sloboda57 at Tsurukhaituye58 for trade relations with Chinese merchants, supporting trade in the older location at Kyakhta59 conducting independent negotiations with the Chinese authorities, etc. In 1731 he was promoted to the rank of brigadier and named commandant of Selenga fortress60) and commander of the Yakut regiment.61 In March 1740 at the rank of General-Major he was dismissed.62

During its first years the Omsk fortress was in the same state had Bukholts had left it in. Subsequent events required further fortifications. In February 1721 the Russian envoy to Beijing, Captain A. Izmailov, was presented with a memorandum, in which stated that the Chinese authorities planned to build a fortress on the Irtysh, supposedly for more convenient diplomatic and commercial relations with Russia.63 The Qing wanted to bring Russia into its struggle with the Zungars. However, the Russian authorities were far from supporting Chinese aggression against the Zungars. In turn, Tsevan-Rabdan sent an envoy to Peter I with a request to defend him from the Chinese khan64 and to send a Russian force to him up the Irtysh, with assistance which would “…to liberate from fear of the Chinese, as he oppresses us”.65

An envoy headed by Captain I. Unkovsy headed to the Zungars for discussions about Russo-Zungar relations, including a proposal for the Zungars to accept Russian citizenship. Unkovsky conducted negotiations about the return of prisoners from Bukholts’ detachment, of which about a 1000 people were held by the Zungars. However, this embassy did not reach its goals.

The embassy of Raguzinsky, as is known, ended with the signing of the Kyakhta agreement in 1727. The Russian authorities ordered Raguzinsky to declare in Beijing concerning the Chinese plans to build further fortresses on the Irtysh: “…Irtysh-river has been in the possession of the Russian Empire from time immemorial, on which the capital of Siberia Tobolsk and many other fortresses and slobodas stand, and for this, the Imperial Majesty in no way will allow the construction of fortress on its possession”.66 Such a position by Russia held off the Qing onslaught against the Zungars and contributed to the truce in the Zungar-Chinese war. The complex international situation required strengthening of the Irtysh frontier fortresses. In these conditions arose the plan to construct a new Omsk fortress (1772). It was drawn up by Engineer-Captain De Granzh, who arrived to the Omsk fortress as a part of the expedition by Likherav.67 De Granzh noted: “The old town on the Omi, is fortified only by a simply palisade and small ditch, currently crumbling and falling apart, which must be rebuilt at a different place”.68

According to the “project” of De Granzh’s, the fortress had to be located at a more convenient place, on the right bank of the Omi. (Construction was subsequently carried out in 1765 by Lieutentant-General I. I. Shpringer.) And in the meantime, the old fortress was fortified and rebuilt. Working on the project and rearranging the fortress was also dictated by circumstances of the 70’s in the 18th century, which entered into the history of Kazakhstan as “the year of great disasters”, marked by the bloody invasion by the Oirats69 against Kazakh lands. Russian authorities were aware of this danger, what a powerful Zungar state represented and took measures to fortify the Irtysh frontier line, a system which the Omsk fortress occupied the prominent place in.

The academic G. F. Miller, who arrived to the Omsk fortress 18 years after it was founded, wrote, that “…behind the fortress along both sides of the river Omi stand many public house, of which Omsk sloboda consist of and which are surrounded by a special ostrog on the northern side of this river. The garrison of this fortress consists of 150 people, and another 200 Cossacks”.70 Until 1734 the Omsk fortress was located in administration of the Tara voevoda chancellery, and later became independent.

And thus, the expedition of Bukholts laid the beginning of a new stage of development of the territory of the Upper Irtysh region.

The foundation of the Omsk fortress played a progressive role in delivering the Turkic speaking and Russian population of the Baraba steppe71 and the Tara uezd from predatory raids by the feudal nomads and the further development of productive forces in the region.

With the emergence of the Omsk fortress, more favorable conditions were created for the production of salt at the Yamysh-lake and trade developed with eastern country at the Yamyshev market: appeared an intermediary strong point on the Irtysh between the town of Tara and the Yamysh-lake, and the threats against the Tara volost72 disappeared.

The foundation of Omsk turned out to influence the struggle of the Kazakh people against the Zungar rulers for the liberation of their lands. Further on, Omsk played an important role in the development of Russian-Kazakh political and social-economic ties, ending in the voluntary entry of Kazakhstan as a part of Russia.

Bibliography

Экспедиция И. Д. Бухолца и основание Омской крепости / Евгений Николаевич Евсеев // Города Сибири : (экономика, управление и культура городов Сибири в досоветский период) : (отдельный оттиск). – Новосибирск, 1974. – С. 47–59.

Словцов П. А. Историческое обозрение Сибири, кн. 1. М., 1838, с. 398–410; Словцов И. Я. Историческая хроника Омска. Материалы по истории и статистике г. Омска. – «Труды Акмолинского Статистического комитета». Омск, 1880, ч. 1, с. 41–50; Катанаев Г. Е. Историческая справка о том, как и когда основан Омск. Омск, 1916; Русский биографический словарь. СПб., 1908, с. 564–565; Палашенков А. Ф. Планы Омской крепости. 1722 и 1755 гг. – «Известия Омского отделения Всеросс. геогр. об-ва Союза ССР», 1960, № 3 (10), с. 25–29; Фиалков Д. Н. По следам Ивана Дмитриевича Бухолца. – «Известия Омского отделения Всеросс. геогр. об-ва Союза ССР», 1904, № 6 (13), с. 61–66; Златкин И. Я. История джунгарского ханства. М., 1964. с. 334–346; Княжецкая Е. А. История одной географической ошибки петровского времени. – В кн.: Путешествия и географические открытия в XV–XIX вв. М. – Л., 1965, с. 57–67; Колесников А. Д. Основание Омской крепости и ее роль в заселении Прииртышья. – «Известия Омского отделения Всеросс. геогр. об-ва Союза ССР», 1965, № 7 (14), с. 133–160; Евсеев Е. Н. Исторические предпосылки основания Омской крепости. – В кн.: Материалы научной конференции кафедр общественных наук институтов г. Омска. Омск, 1905, с. 92–97; Он же. Омск в XVIII и первой половине XIX веков. – В кн.: Из истории Омска (1716–1917 гг.). Омск, 1967, с. 9–40.;

Миллер Г. Ф. История о песошном золоте в Бухарии и о чиненных для онаго отправлениях и о строении крепостей при реке Иртыше, которым имена: Омская, Железинская, Ямышевская, Семипалатинская и Усть-Каменогорская. «Ежемесячные сочинения и переводы к пользе и увеселению служащие», 1760, январь – февраль.;

Slavic term for a military leader. In Russia in usually meant military governor

The original says, «Большого Камчатского наряда»

A small fort. Ostrogs were often detached satellite outposts of the main fortress, serving as watching and signal posts, and allowing for communication to be maintained between fortresses

Known in English as The Great Northern War, 1700–1721. In this war Russia seizing the mouth of the Neva River, where Peter I built Saint Petersburg

A proclamation by the Tsar or an other high ranking state official, that carried the weight of the law

ПСЗ, т. V, № 2811.;

Фиалков Д. Н. Указ. соч., с. 61.;

ПСЗ, т. V, № 2811. Указ Петра I от 22 мая 1714 г.;

Фиалков Д. Н. Указ. соч., с. 61–66.;

ЦГАДА, ф. 248, д. 373, лл. 90-91;

Also known as the Siberian Chronicle, complied by Ivan Cherepanov in the 18th century

An order, from a state organ

The original says, “гарольдмейстерской конторы”

The original says, “Бухольцов, Бухольцевых, Буколтовых”

Prior to reforms of Peter the Great, Russia did not have a regular, standing army. Instead it had collection of irregular formations such as the Streltsy, Cossacks, militia, etc

In his younger years, Peter the Great organized mock battles between soldiers, similar to reenactments today. These units he organized for his amusement later became real military formations

This unit was initially one of Peter I’s “toy soldiers”, see footnote 18 for more

Medieval Russian fort built by Novgorod in Lake Lagoda in the 14th century

ЦГВИА, ф. 2583. Преображенский полк, ед. 1, л. 157.;

Tobolsk was at the time the capital of Siberia. Prior, it was known as Qashliq, the capital of the Siberian Khanate, a successor state to the Mongol Empire, which was conquered by Russia in the 16th century

Mounted infantry

ЦГАДА, ф. 9, Кабинет Петра I, кн. 23, л. 32.;

Matvey Petrovich Gagarin, the then governor of Siberia

The original word is “токарей”

ГАТОТ, ф. 47. Тюменская воеводская канцелярия, д. 3556, лл. 11–13.;

ЦГАДЛ, ф. 9, Кабинет Петра I, кн. 23, л. 32.;

The original says: “32 дощаниках и 27 больших лодках”

A Russian town on the Irtysh, downstream from Omsk

Similar to the district

ЦГАДЛ, ф. 9, отд. И, кн. 23, л. 32.;

Фиалков Д. Н. Указ. соч., с. 61; История Сибири, т.2. Л., 1908. с. 40.;

The original word is “надолбы”

The title of the ruler of the Zungar Khanate. In the original text it is written as “контайша” (kontaisha)

Там же, ф. 9, отд. II, кн. 23, лл. 38-39об.;

ЦГИАЛ, ф. № 1329, оп. 1, д. 8, л. 112.

ЦГАДА, ф. 248, д. 373, л. 199 об.;

A Russian town on the Tom River, northeast of modern day Novosibirsk. To the east of the Irtysh River

Written in Russian as “Сибирская язва”

ЦГАДА, ф. 248, д. 373, п. 201.;

The Julian Calendar, which Russia used before adopting the Gregorian Calendar after 1918

Евсеев Е. Н. Омск в XVIII и первой половине XIX вв., с. 9; Колесников А. Д. Указ. соч., с. 133-134.;

An anti-cavalry obstacle

ЦГАДА, ф. 196, оп. 1, д. 1543, л. 170; ЦГВИА, ф. 349, оп. 27, д. 1062.;

ЦГАДА, ф. 9, отд. 2, кн. 20, л. 142 об.;

Там же, ф. 122. Киргиз-кайсацкие дела, оп. 1, д. 3, лл. 1–2.;

The region of southeastern Kazakhstan. Semireche is Russian for “Seven Rivers”. In Turkic, the region was known as Zhetysu, meaning the same time. The seven rivers refer to the drainage basin of Lake Balkhash

The enemy being the Qing Dynasty. In other words, Peter was offering the Zungars to become Russian vassals

Там же, ф. 13. Зюнгарские дела, д. 1, лл. 1–2.;

Там же, ф. 248, д. 373, л. 201.;

The term “state people” refers to peasants, miners, factory workers, who were owned by the Russian state, opposed to “serfs” who were owned privately by the nobility

The quote is difficult to translate, the original says: «...Набеги и подъезды бывают частые и многие деревни разоряют и берут государевых людей в полон и скот отгоняют и тот их помянутой подбег и подъезды окромя того удержан невозможно, разве в крепких присутствующих местах учинить немалое число крепостей удоволить немалыми воинскими людьми и артиллериею»

Там же, л. 202.;

Там же, ф. 9, д. 47, лл. 31–32 об.;

ПСЗ, т. VII, № 4429, л. 208.;

A settlement free from external rule. Slobodas were often settled by Cossacks. The word sloboda literally means “freedom”

Today called Starotsurukhaitui, in Zabaikalsky Krai, on the border with China

Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727 stipulated that all Russian-Qing trade could only occur at the border town of Kyakhta, which today is on the border between Mongolia and Zabaikal Krai, Russia

Located on the Selenga River, south of Lake Baikal. At the Selenginskiy Spasskiy Sobor, near Novoselenginsk

Бухольц И. Д. Русский биографический словарь. СПб., 1908 с. 564-565.; ЦГВИА, ф. 490, оп. 1, д. 621, л. 6 об.;

ЦГАДА, ф. 286, д. 155, л. 594.;

Златкин И. Я. Указ. соч., с. 351.;

The Chinese emperor at the time was a Manchu, a people of the steppe nomadic tradition, thus steppe nomadic terms were often used in refer to the Qing, as opposed to tradition Chinese terminology

Там же, с. 349.;

ПСЗ, т. VII, № 4749, л. 519.;

Архив АН СССР, Ленинградское отделение, ф. 21, оп. 4, д. 14.;

ЦГВИА, ф. 349, ВУА, оп. 27, д. 1062, л. 1722.;

The Oirats were the western Mongols. The Zungars were a tribal confederation of western Mongols

Архив АН СССР, Ленинградское отделение, ф. 1, оп. 5, д. 7.

The steppe between Omsk and Novosibirsk

Similar to a district

This was fascinating! Thank you for writing. Do Russian historians ever compare Russias drive to the pacific with America’s? The similarity between the two conquests of an “internal” frontier is striking

Olga, Viking Queen of the Rus . . . https://cwspangle.substack.com/p/olga-viking-queen-of-the-rus