The Altai Mining District - Johann Hackmann, 1787 & Karl Ledebour, 1826 & Vasily Sapozhnikov, 1897

Translations on Russia's mining empire in the Altai Mountains

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below are three translations that focus on the Russian Empire’s mining operations in the Altai Mountains. This post is a sequel of sorts to my other translation on the Altai mining region, written by Grigory Spassky in 1809, and covers some of the same terrain that is covered below. Part one can be read here, and part two here.

The first text is by Johann Friedrich Hackmann, titled “The Kolyvan Viceroyalty”, from “An Extensive Land Description of the Russian State, published for the benefit of students by the command of Her Highness the Reigning Empress Catherine the Second”, published in 1787. It is a geographic overview of the Kolyvan Viceroyalty, and was meant to used for educational purposes by Russian students at the time. The author was born in Hanover in 1756, and worked as a professor and researcher at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences. He published works on the Black Sea region, Tibet, and other geographic work pertaining to the territories of Russian Empire. The source for the translation can be found here. The original text can be found here.

The second text is by the naturalist Karl Friedrich von Ledebour, titled “Trip to the Ridder Mine”, from his “Journey across the Altai Mountains and the Zungar-Kyrgyz Steppes”, first published in 1826 and republished in 1993. Born in 1785, Ledebour was a German from Swedish Pomerania, who was invited to Russia in 1805 to be the director of the botanical garden at Tartu in modern day Estonia. He later studied the flora of the Altai region, publishing several works on the topic. The source for the translation can be found here. The original text can be found here.

The third text is byVasily Vasilevich Sapozhnikov, from his “Around Altai. Travel Diary 1895”, which covers his tour of the Zyryanovsk mine. Born in 1861 in Perm, Sapozhnikov was a botanist and geographer, travelling across Semireche, Altai and the Sayan Mountains. He later served as rector at Tomsk University and then as the Minister for Education under Alexander Kolchak during the Russian Civil War. Following the Bolshevik takeover he remained in Russia and conducted several further expeditions to the Altai region, where he studied mountain pastoralism among other subjects. The source for the translation can be found here. The original text can be found here.

Russia’s mining operations in the Altai Mountains first began during the reign of Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century. One of the main focuses of Peter’s Westernization efforts was the modernization of the Russian military, which would allow it to effectively compete with other European great powers. This of course required metals and increased mining, which were necessary for the production of artillery, muskets, naval vessels and more.

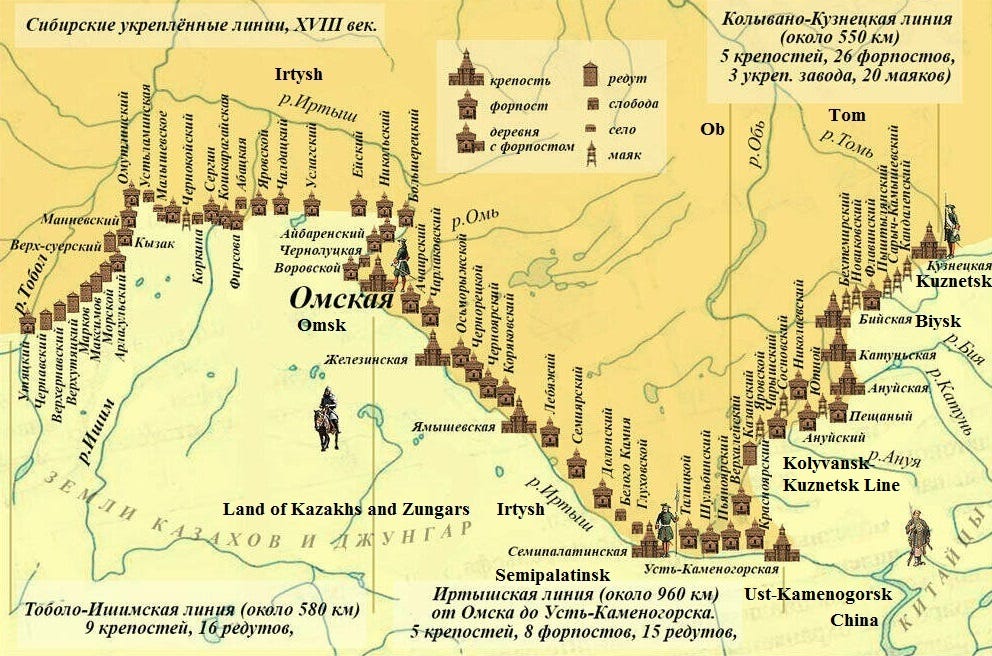

Peter first turned his sights to the metals of Asia in the 1710’s. The governor of Siberia at the time reported to Peter that vast gold deposits existed in Yarkent in the Tarim Basin, which prompted Peter to send an expedition headed by Ivan Dmitrievich Bukholts to conquer Yarkent in 1715-1716. This effort ended in failure, but it did bring Russia to the Irtysh River, where it soon constructed a line of fortresses that guarded Altai and southern Siberia from the rapacious steppe nomads. Shortly thereafter, vast metal deposits were found in the northern and western foothills of the Altai Mountains. Mining operations in the Altai only took off towards the end of Peter’s life. The man principally responsible for creating the Altai mining district was Akinfy Nikitich Demidov, whose father Nikita Demidov earlier in Peter’s reign created and expanded Russia’s vast mining empire in the Ural Mountains, at Ekaterinberg, Nizhny Tagil and elsewhere. Soon enough, Russia was one of the largest producers of iron in the world, in addition to becoming one of the best armed states.

In the 1720’s mining equipment and workers were physically relocated to the Altai Mountains. In 1727 Akinfy Demidov founded the Kolyvan-Voskresensky factory and in 1730 Barnaul founded, which hosted large processing facilities for mined ores. Later in 1736 Zmeinogorsk was founded. Following Akinfy Demidov’s death in 1747, his mines and factories were taken by the imperial family’s treasury, making them not state-owned, but the private property of the Romanov family. Additional mines were soon opened in the south-western foothills of the Altai, with Ridder and Zyryanovsk being two of the most productive sites. By the 1830’s the Zyryanovsk mine produced more silver than either England, France, or Prussia, and by 1870 it produced 1.5 million pounds of silver ore annually. Russia’s first hydroelectric dam was also built at Zyryanovsk, in 1892. The Altai Mountains had become the second largest mining region in the Russian Empire after Urals.

In addition to the Irtysh Line that enclosed the Altai mining district from the southwest, in 1747 the decision was undertaken to built the Kolyvansk-Kuznetsk Line, which would run southwest to northeast, from Ust-Kamenogorsk on the Irtysh to Kuznetsk in Siberia. The Russians feared that the Zungars or Qing Dynasty would invade Siberia and deprive Petersburg of its mining centers in Altai. By the time of Catherine the Great the Kolyvan-Kuznetsk Line was completed and fully modernized, but soon lost all strategic importance as it became clear that the Qing Dynasty had no hostile intentions toward Russia.

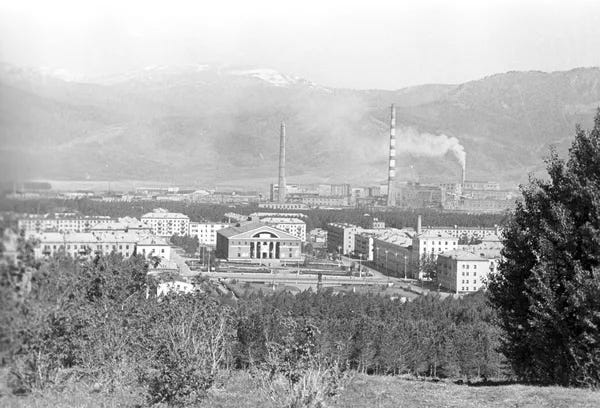

Towards the end of the 19th century the Altai mines began to slowly die. The more easily accessible ores were mostly depleted, and reaching deeper deposits required better technologies and more capital investments. This was not forth coming. The mines had relied on serf labour, and the imperial treasury who owned the mines was slow in adaptation following the end of serfdom in 1861. Ridder closed in 1893. In the early 20th century various foreign companies attempted to reopen and revitalize Ridder and Zyryanovsk, but their efforts failed. The Altai mines only say a new breath of life during the Soviet period, thanks to the state’s increased emphasis on industrialization, in addition to new Western technologies being introduced.

During Soviet era Ridder was renamed to Leninogorsk, but returned to being called Ridder following the independence of Kazakhstan. Today, the Altai mining district in eastern Kazakhstan remains the most ethnically Russian part of independent Kazakhstan. Around Ridder and Zyryanovsk, ethnic Russians constitute around 80% of the population, and over 60% in Ust-Kamenogorsk and elsewhere along the former Irtysh and Ishim Lines.

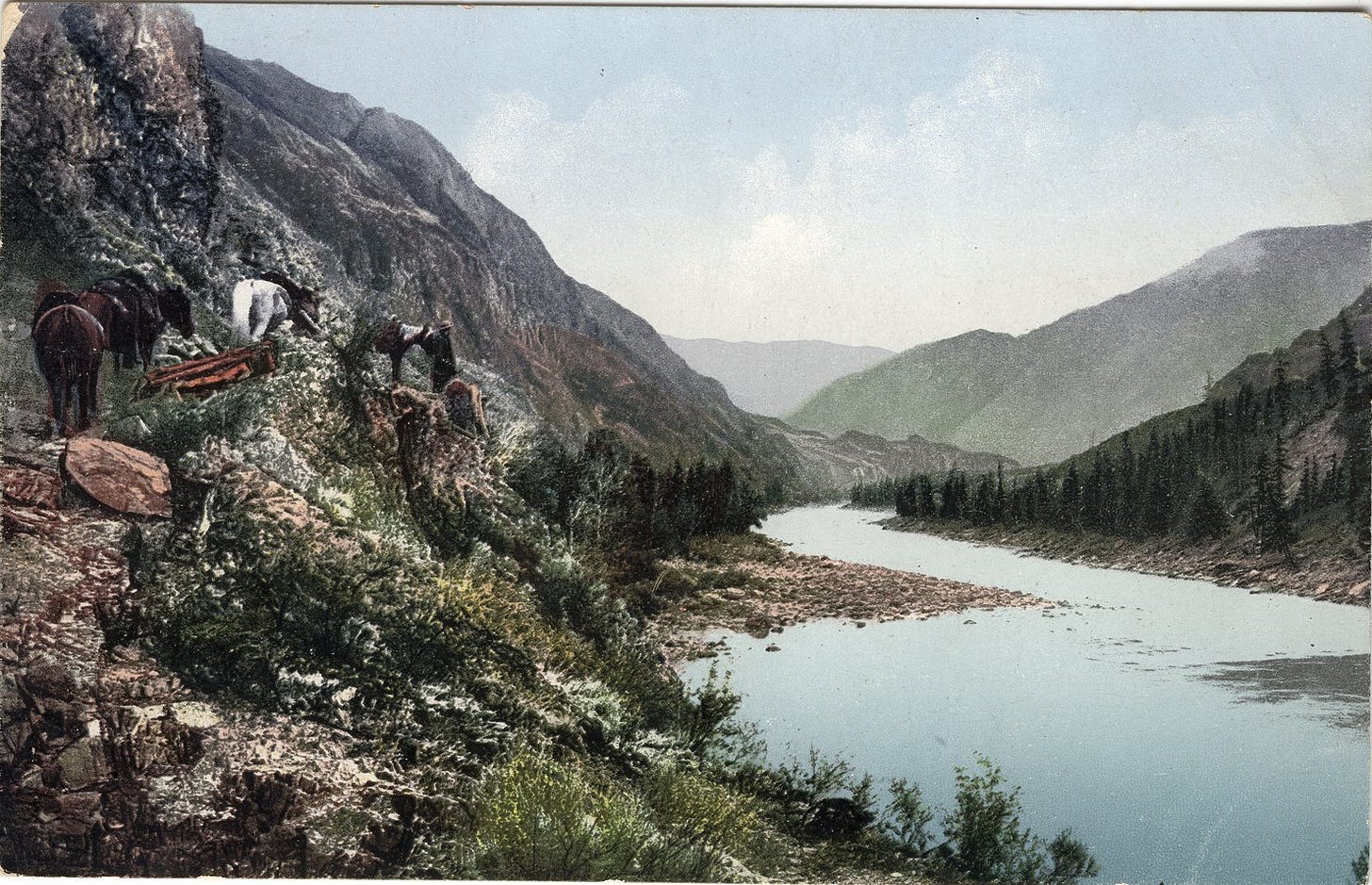

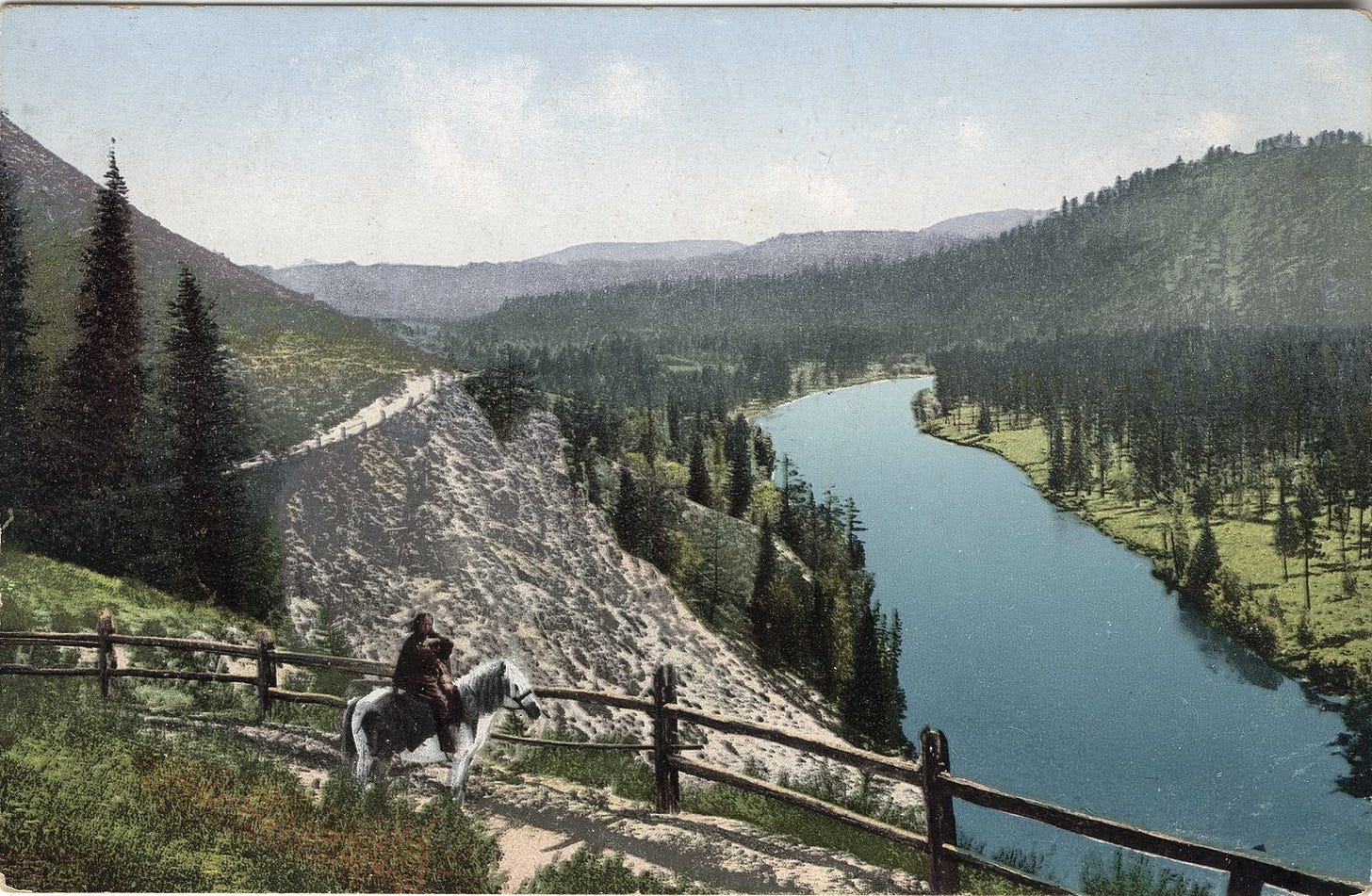

Lastly, while I have not yet been to this part of the world myself, from what I can tell the Altai region in eastern Kazakhstan appears to be one of the nicest corners of world, and would likely be a excellent travel destination, and relatively easy to visit compared to the Altai region in Russia.

The Kolyvansk Viceroyalty1

И. Ф. Гакман. Пространное землеописание Российского Государства, изданное в пользу учащихся по Высочайшему повелению Царствующия Императрицы Екатерины Вторыя. — СПб., 1787.

It is adjacent to the viceroyalties of Tobolsk2 and Irtysh,3 with lands of the Kyrgyz-Kaisaks,4 with Zungaria5 and Mongolia; extending from the southern frontier of Siberia, along the upper parts of the rivers Ob and Yenisei, up to the Tobolsk viceroyalty. The river Irtysh constitutes its western frontier, and the noble parts of the eastern border lie on the river Kan. The mountains of this viceroyalty are rich in metals, the northern half of the Altai Mountains especially containы large deposits of silver and copper, and many zinc and lead ores in addition. The residents are mainly trained in hunting and fishing, mining and other factory work. Cattle raising and agriculture is common. The number of residents is nearly 170,000 souls. Other than the Russians many different Tatars are located there, mainly in the upper regions of the Ob and the Yenisei, and the rivers flowing into them. Around the Yenisei live a few peoples of the Samoyedic tribe.6

In this viceroyalty there are five uezds,7 with the following uezd cities:

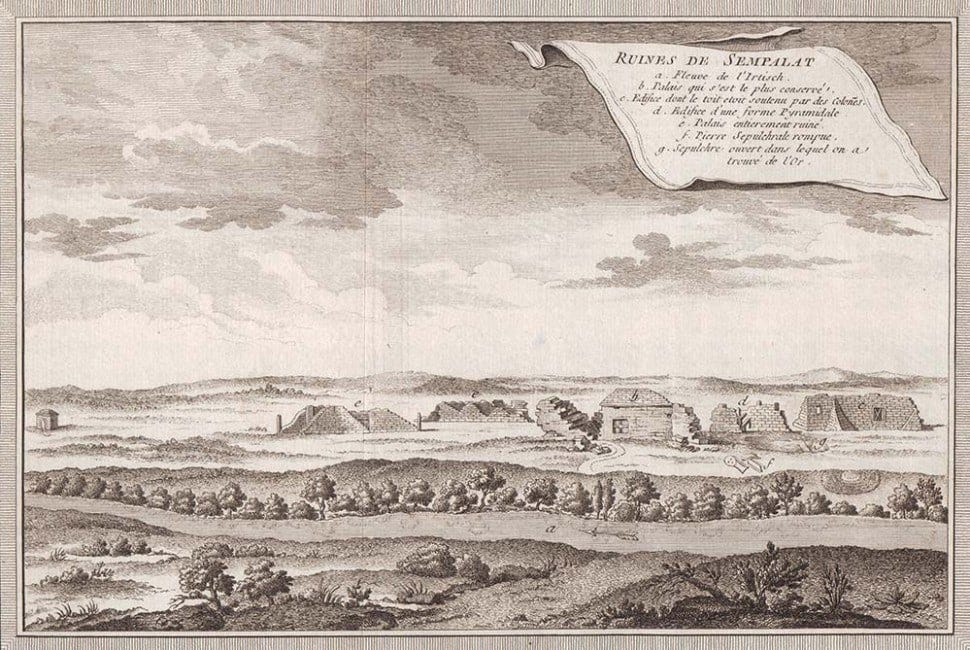

1. Kolyvan, the main city, on the right bank of the Ob, slightly above the mouth of the river Berda, where once stood the Berdskoy Ostrog,

2. Semipalatnoy, city and fortress on the right bank of the Irtysh. A market has been built here for trade with Bukharans8 and the Kyrgyz of the Middle Horde;9 trade with the latter is very important there and consists in large part in horses and cattle. Around this city are Polish settlements, who have had success with agriculture and cattle raising. The Semipalatinsk fortress was founded in 1718 and gained its name from the seven ancient stone houses,10 which were found 10 or 12 verstas away back in the day. Other than Semipalatinsk and the Omsk fortress, which is considered a part of the Tobolsk viceroyalty, three other fortresses were built along the Irtysh, and these five fortresses with many reduts11 and forposts12 constitute the Irtysh Line.13 Below Semipalatinsk lie Zhelezensk and Yamyshev, and above Semipalatinsk is Ust-Kamenogorsk, at 100° 7′ longitude and 49° 56′ latitude. It was given its name because the Irtysh here flows a little higher between the tall rocky shorelines which it rushes through with great force. From this most southern fortress on the Irtysh extends the frontier line, consisting of small forts, forposts and other defenses, across the rivers Ulba, Ubu, Aley and Charysh, up to the Biysk. Located between the Biysk and Kuznetsk there are only three forposts, all distant from each other, because an impenetrable forest is located here which serves to defend the border. Between Kuznetsk and Sayansk, and from there to the eastern border of the viceroyalty, due to the wild mountains, only guard houses were built, in which Cossacks from neighboring villages take shifts living in.

3. Biysk, at where the river Biya joins the Katun.

4. Kuznetsk, at the river Tom, opposite the mouth of the river Kondoma, is at 105° 20′ longitude and 53° 20′ latitude. It was built in 1617.

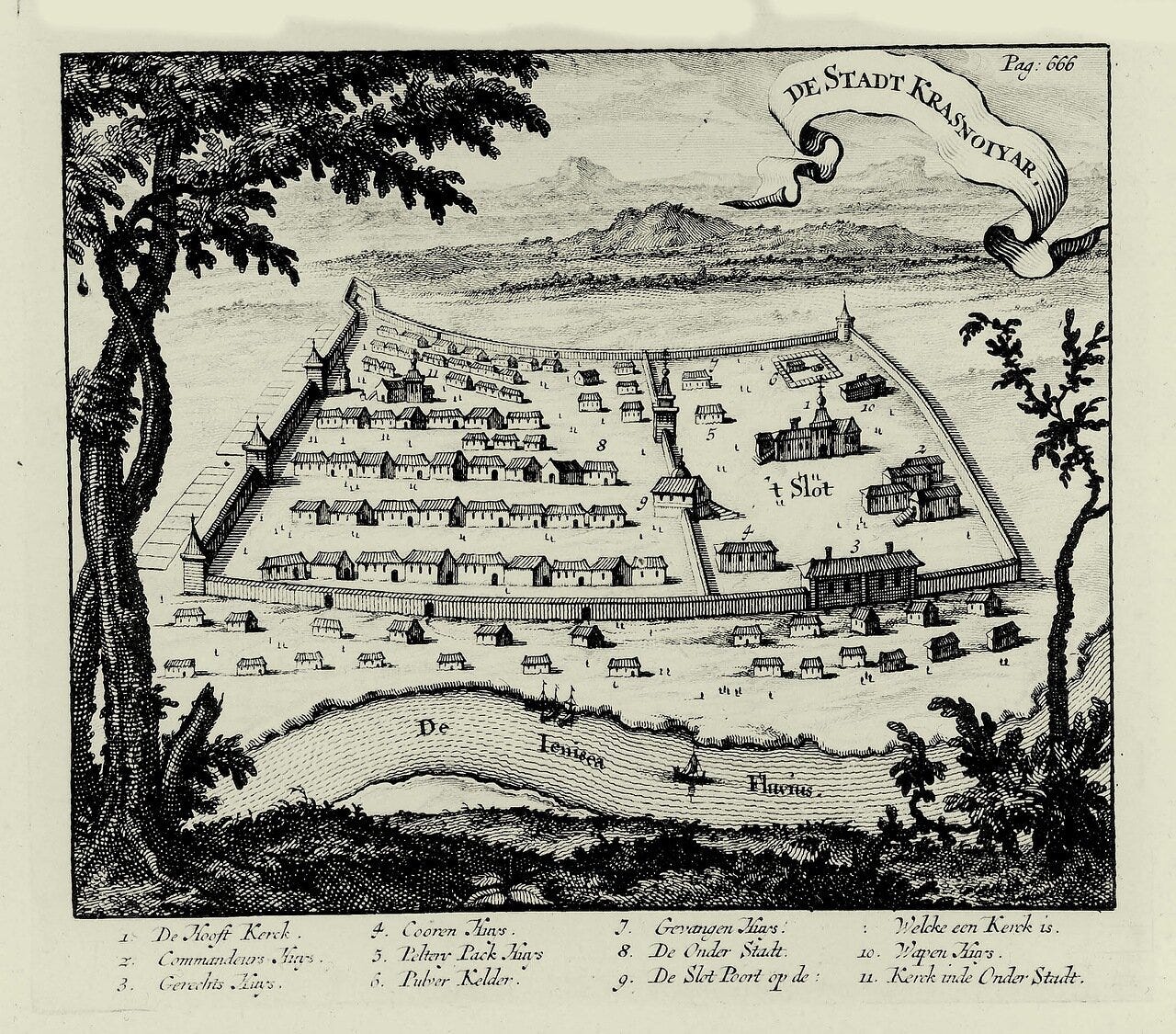

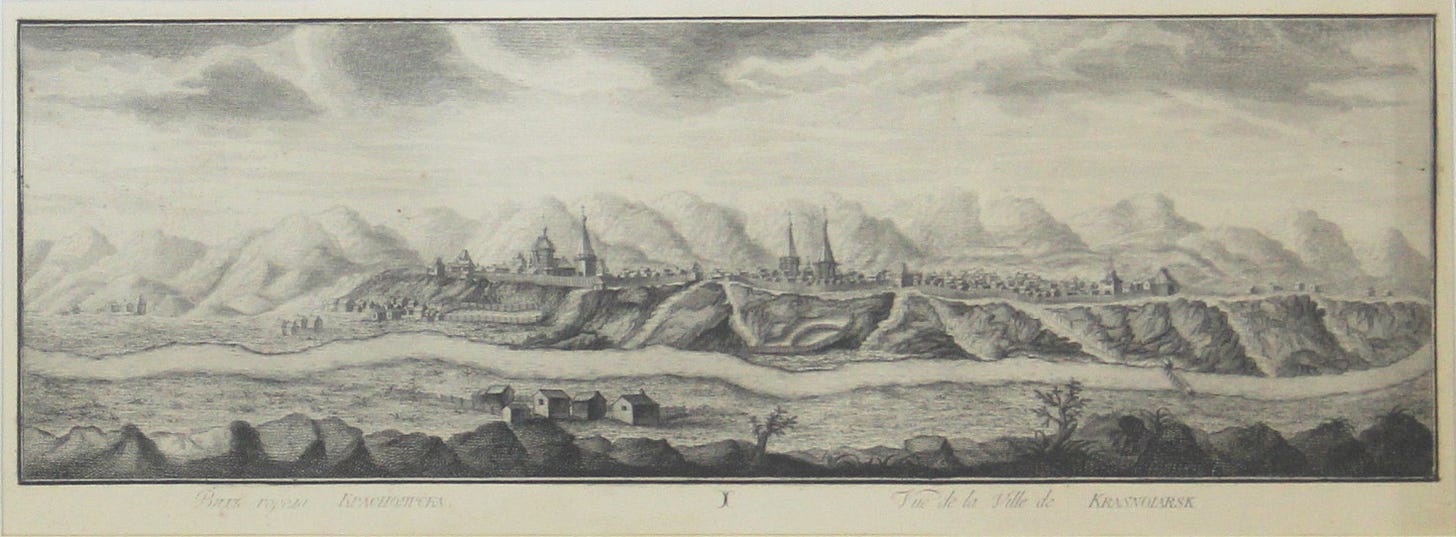

5. Krasnoyask, on the left bank of the Yenisei, where the river Kacha flows into it. Passing merchants heading to the Chinese frontier purchase sable furs other goods here, which are in demand among the Chinese. The founding of this city was in 1627 or 1628.

Mountain factories: Barnaul has the most noble of silver factories, on the left bank of the Ob, at mouth of the river Barnaul. At 105° 3′ longitude and 53° 20′ latitude. Novopavlovskaya, at the river Kasmal, flows into the river Ob. Nizhnesusunskaya, at the river Nizhny Susun, flows into the left side of the river Ob. It was established in 1764, and since 1767 a mint has been located there. Aley is at the river Aley and was built in 1774. The Loktev copper factory, at the river Loktovka was built in 1784, for the large production of copper, which was made into money at the Nizhnesusun factory. The Kolyvan, or Kolyvano-Voskressensky, at the river Belaya is in a high mountainous country. This factory was first founded in 1727, and was then located six verstas14 to the southeast from its current place, near the small lake Kolyvana, from which it received its name.

Development of the Altai mining mountains began in 1727 with Akimfy Nikitich Demidov, who established copper mines in several different places in the mountains. But as the wealth of these mines became known and the Kolyvansk and Barnaul mines were then in operation, they were taken by the imperial treasury in 1747 as the Altai Mountains started producing ores.

Journey to Ridder Mine

К. Ф. Ледебур. Путешествие по Алтайским горам и предгорьям Алтая // Ледебур К. Ф., Бунге А. А., Мейер К. А. Путешествие по Алтайским горам и Джунгарской Киргизской степи. — Новосибирск, 1993.

On 25th of April, 1826, they reported that my travel belongings, which were prepared during my stay in Zmeinogorsk but delayed due to Easter celebrations, were now ready, and on the same day shortly after noon, I sent off to the Ridder Mine. The distance between Zmeinogorsk and Ridder is 184 verstas.15 The route to the first two stantsias16 lay on a straight path going south along the main postal road, leading to Semipalatinsk,17 and further to the Cossack line.18

(…. Ledebour goes through stantsias Ekaterinskaya, Shemonaikha, and the village of Losikha, mostly just noting the local rivers and elevations about sea level - translator)

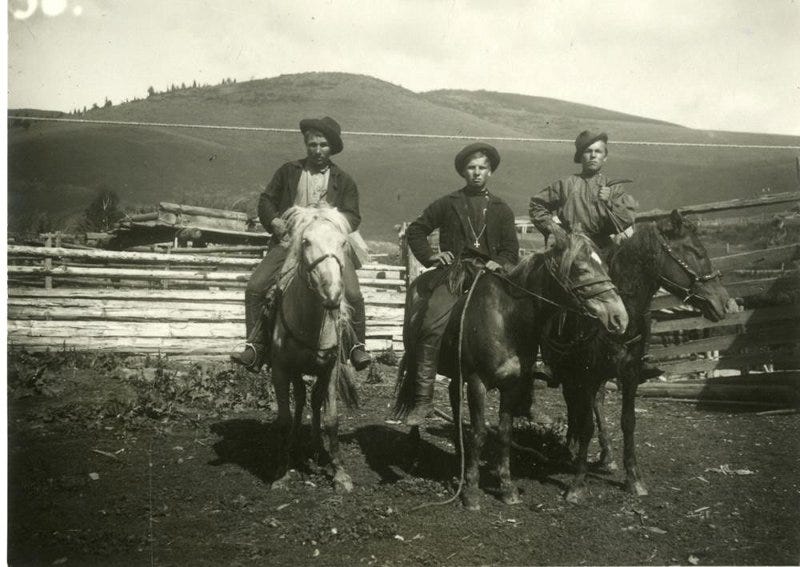

Leaving Losikha, the road to the next stantsia (Ubinsk, 30 verstas, 1210 feet above sea level) immediately crossed a small river of the same name. A large number of Kyrgyz living in felt yurts are settled along the river among some small bushes. The inner construction of the yurts, as well as their outer decorations, makes for a poor sight. Each yurt had a hole in the ceiling to make way for a chimney, around which everything was turned black from soot. These Kyrgyz19 are not engaged in farming and they have very few cattle; their livelihoods mainly come from being hired by peasants, or more often, by Cossacks to herd their cattle. Besides this, they undoubtedly trade in stolen goods, and they are especially known as being horse thieves. Stolen horses are quickly driven across the Irtysh into the Kyrgyz steppes, where the horses then become difficult to find and even more difficult to return back to their owners. Peasants often complain about the nearby Kyrgyz, who often settle around Cossack forposts,20 one of which being located about two verstas from Ubinska. Cossack forposts look like a small village, but in some places you can encounter traces of an ancient fortress, an earthern rampart, cheval de fries21 and something similar.

(… Ledebour travels through the stantsia Ubinskaya, the villages Bysturkha, Cheremshanka - translator)

Butakova, located 1660 feet above sea level, is the last village before the Ridder Mine, which is another 22 verstas away. Nearly all of the villages located between it and Zmeinogorsk are quite large. Peasants here are engaged in agriculture, cattle rising, and many work in beekeeping. Some peasants have more 200 hives. Of course, agriculture in these regions requires improvements and more thorough care. No one fertilizes the land here, fields are cultivated for a few years and then after this, as harvests decrease, they are abandoned and left unused, and a new plot of land is plowed for sowing.

Four types of wheat are sown here, including rye, barley, oats, and a small amount of millet, which gives a harvest of forty and fifty poods.22 Grain is often, and especially during an abundant harvest, left in large piles in the fields and forgotten about until the next year. All throughout my journey I saw such piles from the previous year there and in other places. Peasants sell their surplus grain to stores. The miners receive some of this grain as flour at a fixed low price, which is quite sufficient as food. This of course, is a quite humane thing to do, as the workers do not suffer any harm when the price of grain increases.

Beekeeping was introduced to their district 50 years ago. After two previously unsuccessful attempted were followed by a third that saw beekeepers resettled here with their hives. Since then beekeeping has become so widespread that now in the mining district there are more than 80,000 hives. In many places bees have gone wild and have made their hives in hollowed out trees and crevasses of rocks, so that Cossacks are always on the look out for them in order to collect their honey. Local honey is of an excellent quality, nearly completely white and very aromatic. Food and fruit candies are made from it, which do not at all have the usual taste of honey. The honeycomb wax is so thin and delicate that the honey in relation to the wax is at a proportion of 15:1. Hunting and fishing also provide the local peasants with some income.

The peasants pay the following taxes and obligations:

1. Taxes to the treasury – a head tax, which in Siberia is set at the same amount as in other provinces of Russia.

2. Land taxes, which are similar to other land taxes in Russia, taxes for the maintenance of roads.

3. Worldly taxes – paid to local authorities. Every district, according to how great or small it is, has certain number of volosts. In charge of the volost is a “head,” and a clerk is subordinate to him who is in charge of office work. Besides this, in every village there is an inspector – a starshina23 who keeps order in the village and handles issues as they arise. This position does not give the holder any kind of privileges besides freedom from state obligations. In the absence of the starshina, his wife will often assume his responsibilities, and will carry a rod as a sign of her position and responds to any issues arising in the village.

4. Mining work. These are not obligations to the state strictly speaking, but the mountain-metallurgical factories belong to the Tsar as his private property. Therefore, these obligations are similar to corvee labour, which peasants in the other oblasts of Russia perform for their landlords in exchange for the right to use their land.

(… Ledebour details the insides of peasants homes, reports that they are nice and well furnished - translator)

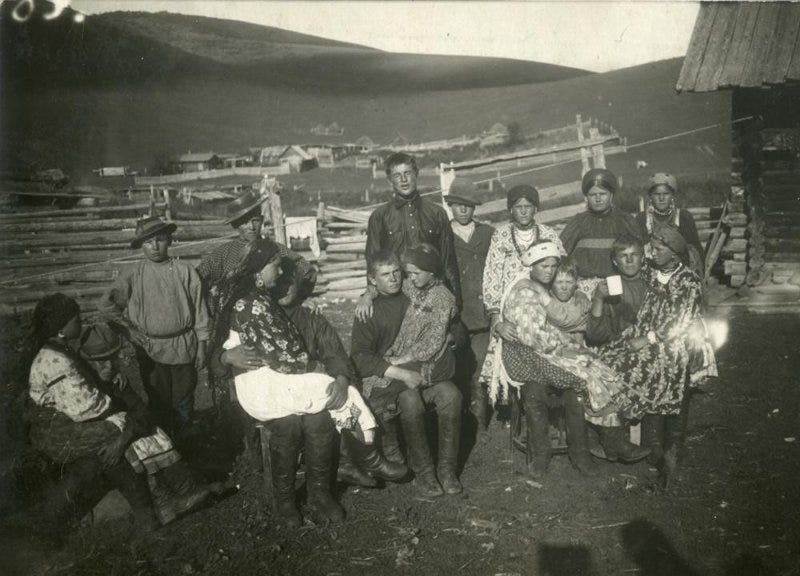

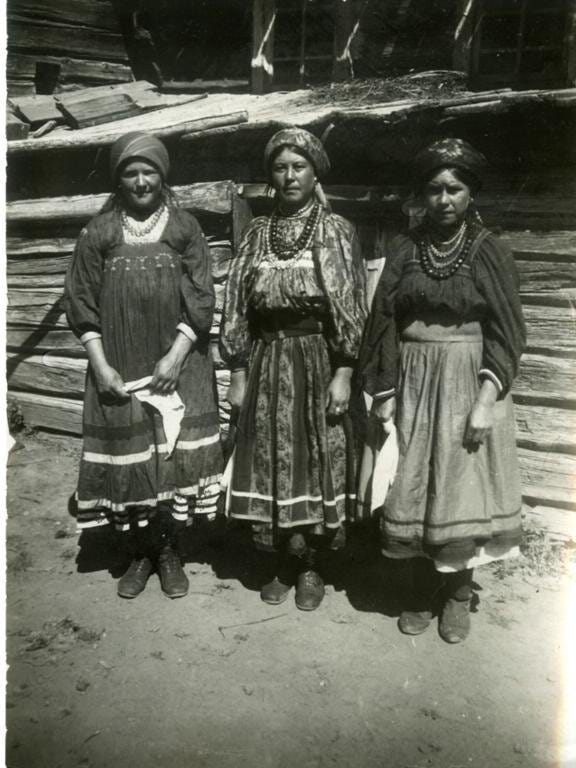

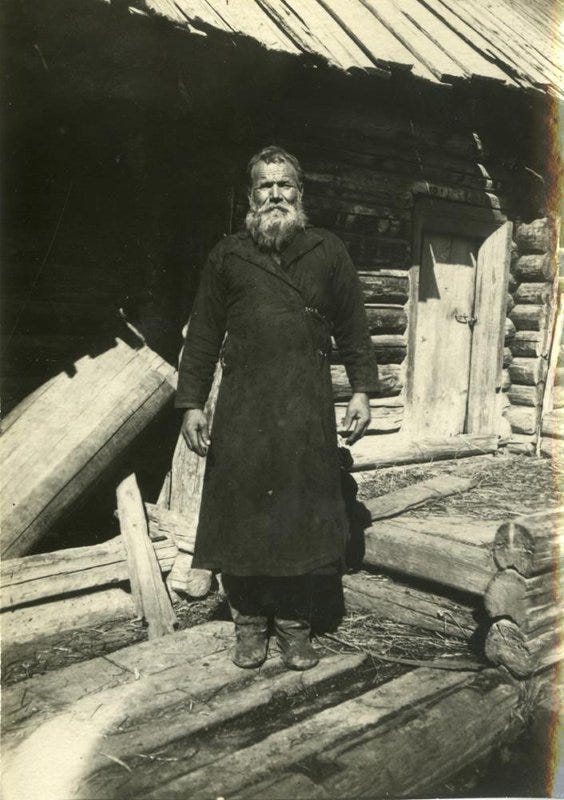

While the peasants are hospitable, they are not very accepting of foreigners,24 and therefore, not every izba25 will allow you to stay the night. Instead, every village has one special izba which has rooms available for rent and where any traveler is accepted… Such hospitality is a great quality of the local peasants, as due to their religion, they are reluctant to have dealings with people of different faiths and even consider their dishes unusable after they have been used by foreigners. The majority of them belong to a sect of Old Believers and during the reign of Empress Catherine II26 they were sent here as settlers. They are very well of, as can be seen from the descriptions above, and the number of residents here are ever increasingly (from 1789 when the peasants of this district fell under the administrative control of the factory, up to the 7th revision which was held in 1815, over the course of 18 years their population has increased to 23,000 people). Some incorrectly assume that their number grows due to exiles, but exiles are entirely absent in the Altai Mining District.

The women here are very fruitful, but many children die during the first months of their lives; this, they say, happens because mothers in this place quickly stop producing milk, or possibly, because there is not enough maternal care for children during the summer months: often mothers spend their days working in the fields, while newborns remain in the village. Among the women I met, not many could be called beautiful or blooming, while the men conversely are in large part big and stately. Dark hair and black eyes are not commonly encountered, people in these parts are mostly fair haired.

(…. Ledebour travels from Butokova to Ridder, mentions rivers and towns, and their distances from each other - translator)

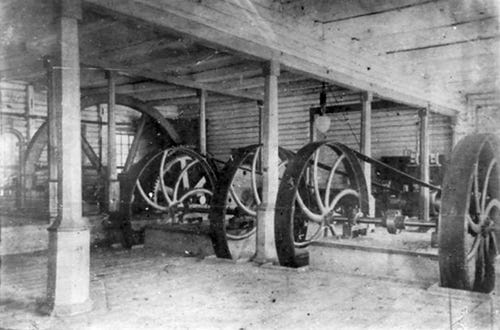

I arrived to Ridder on the 28th of April in the afternoon and thanks to the local authorities, I found myself a prepared and very comfortable room. This place owes its existence to the mountain official Ridder, who in 1783 opened silver and lead mines here, which by 1818 had produced 3990 poods of silver and 2105 poods of lead. And it is not yet fully established just how deep the ores reach here. Water greatly interferes with work, which is currently being done at a depth greater than the river level of Filippovka.27 In order to pump water out from the mines schachtmeister28 Yaroslastsev built a crank machine29 in 1823. With funds provided by the mountain-metallurgical factory, he traveled across Europe visiting many mining factories and studied their machines. Recently a second cranking machine was built to remove excess water, which, likely, would fill up the mine once work reaches a deep enough level. The machine is set into motion by the current of the Bystrukha, with a dam and a canal a half a versta in length that was built for this purpose.

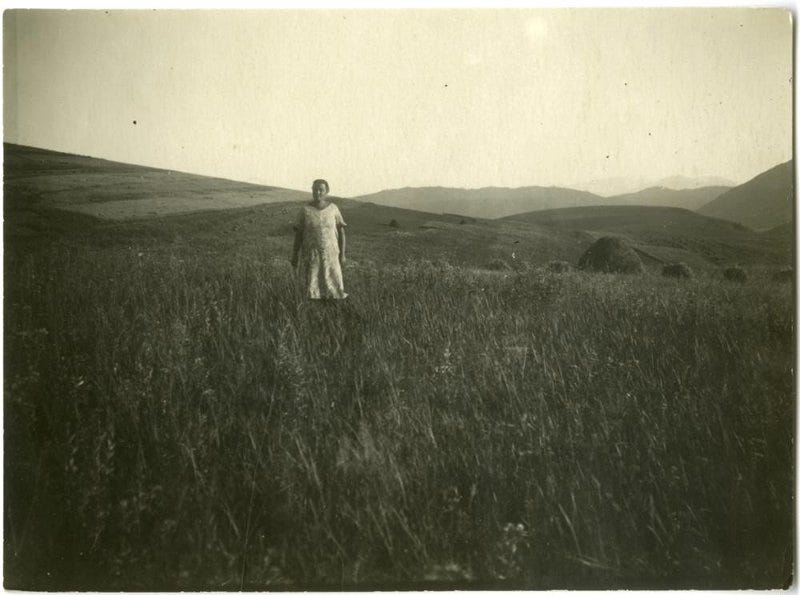

Ridder is located in a wide valley at a height of 2346 feet above sea level. I am now living in the mountains, and through one window of my room I can see Ulba peaks, an impressive sight. Clouds sometimes lie over or around the mountains, completely enveloping them. Large snow massives protrude forth that appear as if they are a thousand steeps away, but of course they only appear so. To the north and to the south, approximately at the distance of a versta, stumpy hills are visible, and some distance further, about 8 to 15 verstas to the south, east and north the view is limited by high mountains which during the time of my stay here were mostly covered by snow. On the northern side of those mountain that are visible to the south and east, snow lies across their peak through the entire summer.

Despite the mild weather, at the beginning of my stay at Ridder a frost set in, and on the 1st of May the mountains were covered in a foot of snow. The climate here in the mountains is much colder than in those places which I passed through on the way from Barnaul. Nevertheless, grains ripen here well enough, although a little later. All kinds of vegetables are grown in gardens here: cabbage, potatoes, cucumbers, pumpkins, onions and a few other, less demanding kinds, but gardening remains under developed. Beekeeping is flourishing, grass growth is superb, and the benefits of the local climate can be evidenced by that nowhere in the mountains do illness such as “Siberian”30 exist, which in locations to the north and west, especially in the Barabara steppe,31 afflicts not only the horses, but also kills many people.

At Ridder, during my stay there, the manager was schichtmeister Belousov, a good old timer to whom I owe much. He is subordinate to the mountain office in Zmeinogorsk and carries out its orders. Ridder is also supplied by warehouses there, including medical supplies. The old infirmary was quite small and a new building was being built to replace it with beautiful rooms with high ceiling; the infirmary was moved to its new location on the day just before my departure from Ridder. The infirmary is served by a young doctor and few assistants; the infirmary has a garden, in which among other things, cultivates rare local plants.

I am joyful to see that in all of the mining district there is great care taken for the health of the workers. However, Ridder is considered to be an place of exile for the local workers, who are placed under stricter supervision than in compared to other places, and in particular, there are no taverns here and in general vodka can only be delivered here with special permission from the commander.

The position of the workers, who are seemingly the only residents of this village, is in general quite good. However it should be clarified first, that in mining affairs there are two categories of workers: those who actually work in the mines and peasants assigned to the mining district. The latter are obligated to cut lumber, create charcoal, transport firewood, coal, ores and fluxes32 to smelting furnaces, and also to repair dams after floods, which they do without being forced to as the welfare of their own farms depends on it. Their work is divided by what is done on foot and with a horse. The first mostly consists of cutting down trees and burning coal, and in the second, mostly consists of transport. Annually, each assigned peasant is obligated to work 17 days on foot and 12 days with a horse.

Until 1779, assigned peasants were obligated to work in the metallurgical factories instead of paying the head tax. After this year, their obligations were more precisely defined, in order to protect them from the arbitrariness that existed prior. At this time the head tax was set at 1 ruble and 70 kopeks, and the work that is imposed upon them was valued at the same sum. Now it has been set that peasants will pay a head tax of 1 ruble and 70 kopeks, as is paid in other regions of Russia, and for each day they work they will earn 3 kopeks. The entire sum, which on average is about 2 rubles and 40 kopecks, and is paid annually by the factory. However, not all peasants are used for this work; a part of them, often a third, are free from it. The mountain council, made up of the managers from the most important mining-metallurgical factories and mines, all under the control of the Kolyvan factories, is gathered in Barnaul every spring and plans out what work is to be done and how much for the upcoming year, and assigns work orders to the volosts who then assign work to specific workers. (…) Affairs are complicated in that villages are in large part located at a distance from the factories and mine. For example, peasants, who live in the areas around Barnaul, are required to work in Zmeinogorsk, and peasants from the northern volosts of Kolyvan mountain district are forced to work in Barnual and Suzun.33 There are entire areas within the existing territory of the mining district where there are no factories or mines, but the peasants of these regions are not free from their obligations despite the distances. Nevertheless, many peasants do not do this work themselves, and instead hire other peasants or workers if it is economically feasible. The number of assigned peasant at this time is around 87,000 souls.

The other category of workers are the actual miners, who are always meant when speaking about workers. Some of the mine workers are recruited from among the assigned peasant, and some are recruited from the children of miners, who, as it is said, are called hereditary workers. Currently their number is (in 1826) 17,514 people. They are considered military personnel and receive similar supplies and provisions. The first amounts to 20-36 rubles a years. If we were to know nothing about these people and their way of life, we would be inclined to consider them to be very poor, but this is absolutely incorrect. Their obligations are reminiscent of corvee labour, which peasants who live in other regions must perform. However, thanks to their current position, not only are of their living needs provided for, but their activities and hard work also open up the path for prosperity for them, as I have often observed. They are completely insured from any need, because they are supplied by treasury warehouses, where provisions are so plentiful that their stockpiles exceed the needs of the workers. They live with their families on factory territory and when free from working hours they occupy themselves with household affairs and gardening. The majority of them have their own izbas, gardens, horses and large horned cattle. They cultivate their fields, mow as much hay as they need and can freely cut down any tree in the forest that they need.

There is a lot of work to be done in the factories, which must be done uninterrupted, but there are some that do stop on Sundays and on holidays. Some of these workers relax on these days, but on all of the other days of the year they must work. Another part of the workers, alternatively, work two week in a row, not halting for Sundays or holidays, and then relax for the third week.

The number of working days in a year is approximately the same in both cases. But the most diligent owners prefer to have the entire free week at their disposal as this is more profitable for them. Everyone is obligated to work 12 hours a day, followed by 12 hours of rest. As work in the mines and in the smelting furnaces must continue without interruption, workers work in two alternating shifts at day and night.

Hardworking and tidy households spend their free days doing more than only household work, but find the time to work for others in exchange for daily pay. Peasants search for such work during all times of the year. If the Tsar’s Cabinet paid workers only 6-7 kopeks a day, the earnings for the typical worker, considering the low cost of food, are very high – each worker receives 5-6 rubles a week, and during the haymaking and harvest period – up to 10 rubles. As was already said, a good homemaker has a horse, cows, sheep and runs profitable beehives. Hay can be cut anywhere in unlimited quantity, because there is a great deal of free land here. None of the meadows here have a specific owner. In all of the mining district, land is generally owned by the state, who rents it out to private persons. Other than this, workers are busy with fishing and hunting, and are often kept for several days and sometimes a week in the mountains, where there is much game and fur-bearing animals. Hunters know the mountains very well and are the best guides. In autumn workers often collect pinecones and earn around 100 rubles a year selling them (these pinecones, which merchants search for, are then transported all across Russia and are considered a delicacy). Unfortunately, cedar – this wonderful tree – is already beginning to thin out in many places because some cannot be bothered to climb up its truck and collect them, and instead chop the tree down. It is difficult to fight against this predation, although publications have strictly forbidden this several times now.

The children of the miners are placed in special schools, where they are trained beginning around the age of 10. Upon completing school, or sometimes later depending on the physical development of the child and other circumstance, boys are required to begin working. They receive provisions and some supplies. The work they are used for is mainly breaking and sorting ores, which the boys learn very quickly how to do. Every day they are given a specified task, and upon completing it they can go home. When the children grow up, they join the actual miners, they receive a large salary and every third week they are free from work, which they did not have as ore breakers. Many of these miners know how to read and write, and some are very knowledgeable and wealthy people, although these cases should not be considered common. Here, and in general everywhere, wealthy people are hardworking, they are provided with all necessities, whereas the easy-minded and the lazy are in a beggarly condition. This is especially with the case of those who drink excessively, who, unfortunately, are commonly encountered. However it must be noted that in all of Siberia I did not see one beggar; the last beggar I encountered who asked for alms was in Nizhny Novgorod.34

The firmly set term of service for a miner is 40 years. But if the worker losses his health at a prior time or some sort of accident causes him to become an invalid, he retires and receives a small pension. Most often, unlucky cases and injuries occur when ores are being blasted with gunpowder, usually due to the carelessness and recklessness of the victims themselves. During our stay at the mine when rocks were being blasted, the blaster asked us not to approach the point of danger, while he himself fearlessly approached it. Often, when the wick has already been lit but the explosion appears to be delayed, they go to check on it; often with this the explosion suddenly goes off, and often causes major injuries. In such cases medical aid is provided at the hospital on the territory of the factory to which the workers belong to. If they remain permanently disabled, they either receive, as was previously mentioned, a payout and retire, or (if the injuries are not too significant) they are transferred to another line of work which they still have the strength to do.

The worker who stands out with their moral qualities and good senses is promoted to the position of junior overseer and receives an increased salary. He is promoted to the position of an unter-officer, but the length of his working hours remains the same. However he freed from work in the mines, which now he only observes. The favourable circumstance for the miners of the Kolyvan mining-metallurgical factories are, of course, due to the depth of the mines which means that temperatures remain unchanged throughout the year. Although the winter frosts in this place are often harsh, the temperatures in the mines remain around 10 to 12° R35 above the point of freezing (the situation is otherwise in the mines at Nerchinsk,36 which are very cold). However factory work here in winter time is very difficult, particularly for workers who carry coal: they are in the smelting furnaces with a monstrous heat, followed by a powerful frost.

A few verstas further from Ridder is the Kryukovsky silver mine. It was opened in 1811 by Kryukov, and received, as is customary, its name from its founder and has become one of the richest mines in the Kolyvan mining district. According to calculations made in 1818, it contains 7851 poods of silver, but since that time further amounts have been discovered.

Zyryanovsk

В. В. Сапожников, профессор Императорского Томского университета. По Алтаю. Дневник путешествия 1895 года. — Томск, 1897.

Departing from Berel on the morning of the 10th of August, I only arrived the next day late in the evening to Zyryanovsk.

The factory is located in an ugly, treeless, flat ground, where small hills are within sight 10 versts37 away. Rows of grey houses surround the large factory structure, where silver ores containing gold are processed, however, the processing of silver is not completed here. The raw material is prepared and processed before being sent to another factory. The mines lies almost entirely under the whole village, and the underground system of tunnels runs 18 stories deep (they reached down to the 19th when I was there). Crossing through the horizontal gallery of mines, it was somewhat strange to hear from the guide, that we now located underneath the church, and then under the electric station, etc. I determined the pressure and temperature at the depth of the 18th floor: the thermometer showed 10.75 °C, and aneroid38 showed 730 mm, whereas on the surface the pressure was 713 mm. So, if it is considered that the absolute height of Zyryanovsk is 514 meters, then the 18th level of the mine is 307 meters, or, that the mine is 207 meters deep. — We climbed up a continuously vertical shaft, where nearby in the dark was a large drainage machine working with a creaking noise.

Along with the absence of trees, Zyryanovsk suffers from a second unpleasant circumstance, namely, the absence of clean water. The only nearby river is the Maslenka creek, which has little water and is strongly polluted, not to mention that its water very quickly clogs boilers. However, not far from Zyryanovsk there is a remedy for the boilers; namely, 12 versts to the north, near a small separate branch of the factory with amalgamation bowls for separating gold, there is a river with very soft water that can completely clean a clogged boiler within a week by boiling this water under a low pressure. I managed to see this simple operation myself.

“наместничество”

The then capital of Siberia, located on the middle Ob River

Irtysh River which flows around the western Altai Mountains, then joining with the Ob River and flowing into the Arctic Ocean. The Irtysh River south from Omsk formed Russia’s border with the Kazakh steppes

Under the Russian Empire, the Kazakhs were usually known as the Kyrgyz or the Kyrgyz-Kaisaks. Only under the Soviet Union was the name Kazakh adopted

Modern day northern Xinjiang, located south of the Altai Mountains and north of the Tianshan Mountains. The name from the Zungars, a Mongolian tribal union was rivaled the Chinese Qing Dynasty for mastery of Inner Asia before it was finally destroyed in the mid-18th century

An Uralic speaking group of peoples, native to Siberia. The largest Samoyedic group today are the Nenets

Equivalent to a district

Bukhara is an oasis city on the Zerafshan River in Central Asia. Often the name “Bukharans” was used generically for all Central Asian merchants

The Kazakhs were divided into three hordes, with the Middle Horde in modern day northeastern Kazakhstan facing the Irtysh

Semi (семи) = seven, palat (палата) = houses. These were ruins built by the Buddhist Oirat Mongols, later known as the Zungars

A fortification typically outside of the fortress

An outpost

See footnote 3

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 kilometers / 3,500 feet

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 km / 3,500 ft

A type of Cossack settlement

A major fortress-city on the Irtysh river, today known as Semey and located in Kazakhstan

The Irtysh Line, also known as the Siberian Line, a line of fortified settlements running along the Irtysh river from Omsk to Bukhtarma

Actually Kazakhs. The Russians called the Kazakhs Kyrgyz until the Soviet period

An outpost

Anti-horse obstacles, made from wood. Similar to the barbed wire obstacles used in the First and Second World Wars to block infantry

Old Russian unit of measurement. Approximately 1 pood = 16.38 kilograms / 36.11 pounds)

Equivalent to a sergeant

“иностранцев”

A Russian peasant or countryside house

Catherine the Great

A river in the Bukhtarma basin further south in Altai. See my translation of Spassky’s “Journey Across Southern Altai”

Junior mining rank, “шихтмейстер”

“шатунную машину”

This likely refers to “Siberian Anthrax”

The region to the east of the Irtysh River up to the northern Altai plain. This region is particularly wet, with the inhabitant prone to diseases. John Bell while travelling through this region in the 1720’s noted that the nomads were often afflicted by a disease that might be this “Siberian Anthrax” as well

“плавни “, a material that is added to ores during the smelting process

Located down the Ob River from Barnaul

Several hours east of Moscow

Ledebour is using the Rankine scale here. The freezing point of water is 491.67 R

In the Trans-Baikal region near the Chinese-Mongolian frontier

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 verst = 0.66 mile (1.1 km)

A barometer that measures air pressure