Breakfast with the Chinese - Alexander Geins, 1865

Translation of a Russian encounter with China's peculiar dinning customs

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of an excerpt from Alexander Konstantinovich Geins’ “Дневник 1865 года. Путешествие по Киргизским степям” (Diary 1865. Journey Across the Kyrgyz Steppes). Geins was a Russian military officer who served in the Crimean War and participated in the defense of Sevastopol, where he suffered a concussion and eye damage. Later, he joined the Russian armies during their conquest of Central Asia, and wrote a travelogue acclaimed for its geographical and ethnographical observations. The original text in full can be found here. The source for this translation can be found here.

The focus of this excerpt are China’s peculiar dinning customs, which as noted by Geins, are uniquely communal with a strong emphasis on sharing. Unlike European or American cuisines, many dishes in China are meant to shared. Typically they consist of a large plate or bowl, placed in the center of the table, and dinners pick or scope out portions for themselves. This of course is radically different from Western dinning, where individuals have their own plates. Also, it should be noted that most Chinese food found the West has been Americanized to some degree, both in terms of ingredients and dinning style. For example, General Tso’s chicken and fortunate cookies are entirely American-Chinese innovations. Outside of China, real, authentic Chinese cuisine tends to be found in more upscale restaurants that cater towards an almost exclusively Chinese clientele.

Naturally, from a Western perspective (in a global context Russians are “Westerners”, which is just a colour neutral term for “white” or European) Chinese dinning customs might appear very strange or even off putting. These cultural differences should not be overstated though. Personally, I had no problem adapting to Chinese dinning customs in the past and I generally like (real) Chinese food quite a bit.

A note on the historical context of this translation. The meeting described below took place during the Dungun revolt, which raged across Chinese Central Asia during the 1860’s and 1870’s. The revolt began among the Dunguns, the Russian term for the Hui, who are Chinese Muslims and are mostly found in the modern Chinese provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia. The revolt soon spread to all Muslims in the northwest quarter of the Qing Dynasty. An adventurer from Kokand named Yakub Beg took over the Tarim Basin and ruled it as a private fiefdom until a Qing army came and reconquered the region. The Ili valley, with its capital of Kuldja, is somewhat isolated from the rest of Xinjiang, and was thus spared from the Muslim revolt for some time. Later, Russia occupied the region but later returned it to China in 1881.

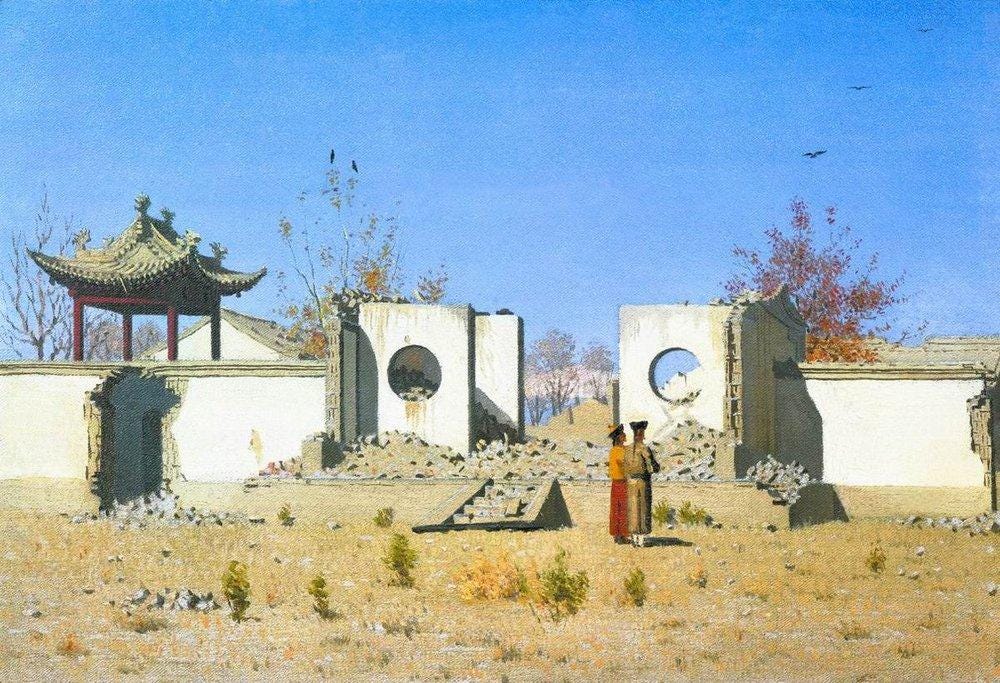

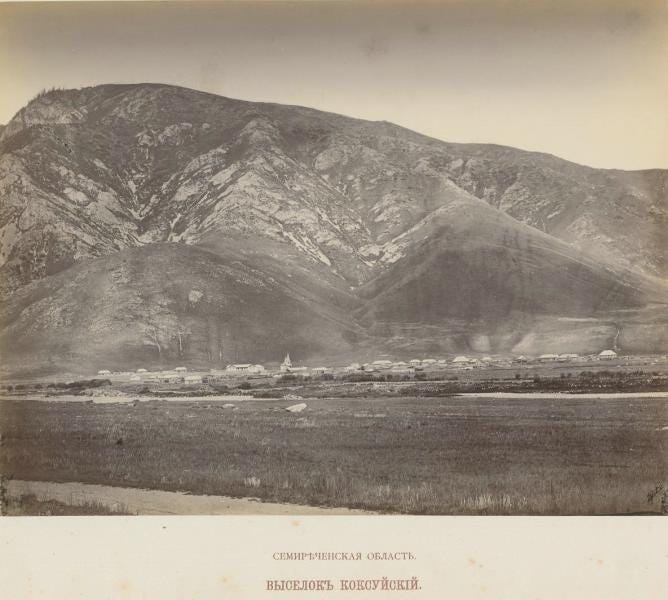

The setting of this excerpt, the Koksui piket (an outpost settlement meant to serve as a forward guard and watch post), was founded in 1855. It was later made into a Cossack stanitsa and settled by Cossack and peasant families. It was located on the Koksu river in Semireche in southeast Kazakhstan, at the entrance of the Koksu gorge in the Zungarian Alatau Mountains, a range that formed the Chinese-Russian border (now Chinese-Kazakh border). Today it is the village of Koksu, a small settlement southeast from the city of Taldykorgan.

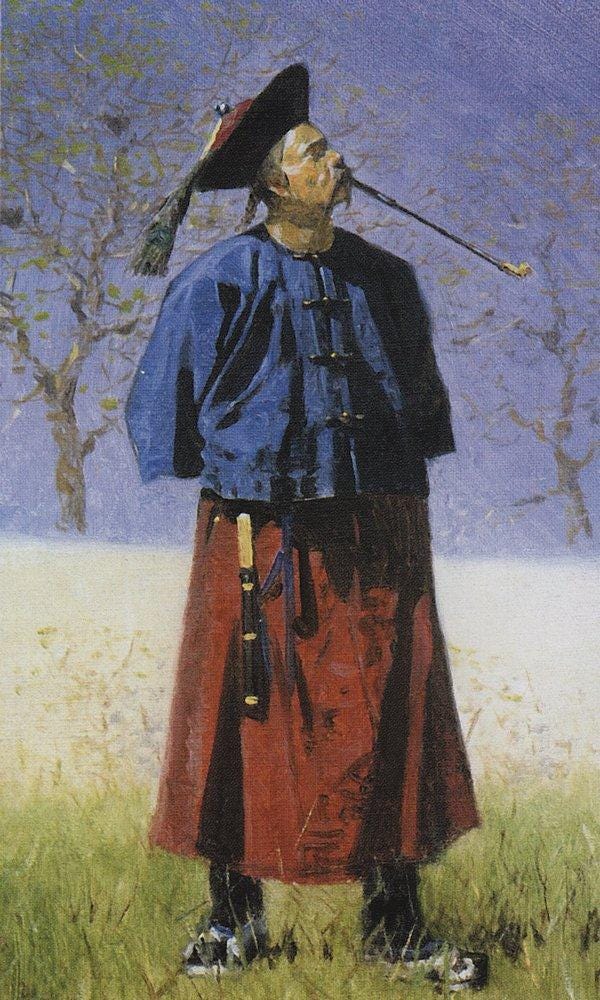

Lastly, it should be noted that in all likelyhood, neither Sa-Galdai nor his subordinates were actual Han Chinese. The Qing Dynasty, China’s last empire, was headed by the Manchus, a semi-nomadic, semi-Sincized people from Manchuria. In the northwest of the empire in modern day Xinjiang, most of the officials and military personal were either Manchus or Mongols, with Han Chinese representing a small minority, who were mostly merchants. Thus, the “Chinese” in this excerpt are likely Sinified Manchus or Mongols.

Breakfast with the Chinese

Breakfast was waiting for us in the house (at the Koksui piket), which we were invited to by the Chinese colonel who lives here. In general there were many Chinese there. Due to the Dungun uprising Kuldja had been cut off from all communications with the rest of China. That year, the jian-jung of the Ili province issued a request to General Kolpakovsky for permission for Chinese officials to travel through our territory from Kuldja to Khobdo in order to collect salaries for their forces. Kolpakovsky gave permission for this. The officials safely transported about 150 pounds of silver by relay along our postal line. Since then all communications with Chuguchak, Khobdo and Peking from Kuldja transited through our territory. But the Dunguns, having learned about these communication routes, blocked Kuldja from the west. That is why one of missions carrying a part of the 150 pounds of silver, going from Khobdo to Kuldja, was forced to stop at the Koksui settlement. The commander of the transport mission Sa-Galdai-Simbo (colonel Simbo) and two dozen others, including his Chinese subordinates, set their camp up, consisting of a number of yurts. He then rented an apartment from the Cossacks.

And so, we invited Sa-Galdai to breakfast. He appeared in full parade uniform, in other words, in a uniform hat with a blue ball, with bronze fastings with long sable tails and peacock feathers attached to the back of the hat and hanging down. He bowed down and gave us his hands. Behind him were two Chinese, with one wearing a hat with a copper ball. After discussing various general subjects, asking Girs who the colonels are, who is the captain and who is the secretary, Sa-Galdai showed us some sort of bronze ball in his hand. He had brought a pipe with him. At once upon blowing smoke from it, Sa-Galdai wiped the mouth piece and gave it to Girs, and then taking a puff himself, he passed it to us in order again. Each of us, as politeness entails, pretended to smoke for some time, and then passed the pipe back to Galdai. We talked through two translators. One of the Chinese who came with Galdai could speak in Kyrgyz1 language and conveyed Galdai’s words to our translator, which were then translated to us.

We could not get any information on who the Dungun were from Galdai. In response to each of our questions of a political nature he said only that until Russia helps, they will not be able to manage the Dunguns, and that Russians only has to commit a very insignificant number of forces and the Manchus will be able to restore peace.

Breakfast was served. We poured the Chinese vodka and drank a glass ourselves. Galdai drank, then poured a glass of beer and after drinking a little, gave it to Girs. After this he again took a small drink and gave it to me, and so on. We again pretended to drink from the glass that was offered to us. The unclean manner of how the Chinese drank made us cautious. While starting to eat, the Chinese pulled out a knife that was hanging from his side and two bone sticks. All this was found in one sheath. The bone sticks, put together, served a spoon, and when apart they were like a fork. Galdai ate quite a bit, and drank vodka even more. Occasionally he gave us pieces of meat from his plate. After the first dish, one of the Chinese placed a plate with a cut up piece of meat on our table that he brought from Simbo’s apartment. Galdai forwarded the plate to us one by one. After the second dish of ours the Chinese treated us to a different dish (cold pork), again brought from his apartment, and had some kind of disgusting seasoning, reminiscent of French mustard flower. After our third dish the Chinese brought out dirty bliny.2 Having noticed how insatiably the two Chinese were looking at the decanter of vodka near Galdai’s chair, we poured them a glass. One of them, the older one, drank at once, the other drank in a different room – such is their etiquette. The dishes were eaten in the same order they were served, all while standing. Galdai explained that they cannot sit in his presence.

After breakfast Galdai turned out to be half drunk. Upon our request, he showed us his bow, arrows, tea pot,3 saddle and sword. On the topic of guns, he said that at close range bow and arrows are better.

We headed back home to the Koksui piket two o'clock after lunch time, having given Galdai various trinkets.

Actually Kazakh language. Russians called Kazakhs Kyrgyz, and Kyrgyz as Kara (black) – Kyrgyz up until Soviet times.

A type of Russian pancake

The original word is “турку”. This appears to be a tool for making coffee of Turkish origin. I assumed the Russians referred to tea items with the same terminology, but I might be entirely wrong

Note to self: степям is a cognate of "Steppes" because it is pronounced "stepyam"

Russia is a language with different connections...

This was fascinating. Thank you for writing! Also — Chinese vodka? 🤮 and what was in the pipe?