Notes on Chinese Turkestan, Tibet and Kashmir - Mehdi Rafailov, 1811

Translation of a commercial-reconnaissance report on the trade routes from Russia to India through Chinese Turkestan. An Afghani Jewish spy in the Great Game

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Translator’s Introduction

Below is a translation of the travel notes written by Mehdi Rafailov, a Jewish merchant from Kabul, Afghanistan who served as a spy and diplomat for the Russian Empire. Using his profession as a merchant as cover, he conducted reconnaissance in Chinese Turkestan, modern day Xinjiang, and served a liaison between Russia and princes in northern India. The source for this text can be found in the book “Российские путешественники в Индии XIX-начало XX в.: документы и материалы” (Russian Travelers in India 19th to beginning of the 20th century: Documents and Materials), edited by Petr Mikhailovich Shastitko and published by the Institute of Oriental Studies, Academy of Sciences, USSR in 1990. The book can be found and downloaded here (an account on Vkontakte might be necessary for this). I learned of Mehdi Rafailov and discovered this book from “Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s” by Alexandre Andreyev.

Information on Mehdi Rafailov is limited, but what is know is that he was a Jewish merchant from Kabul employed by a Georgian nobleman and merchant named Semyon Madatov and that he could speak a number of oriental languages including Kashmiri and Punjabi. He was also known to William Moorcroft, a Englishman who managed the British East India Company’s stud farms while also serving as an intelligence agent. According to Moorcroft, Rafailov was originally born in Persia and later converted to Russian Orthodoxy.

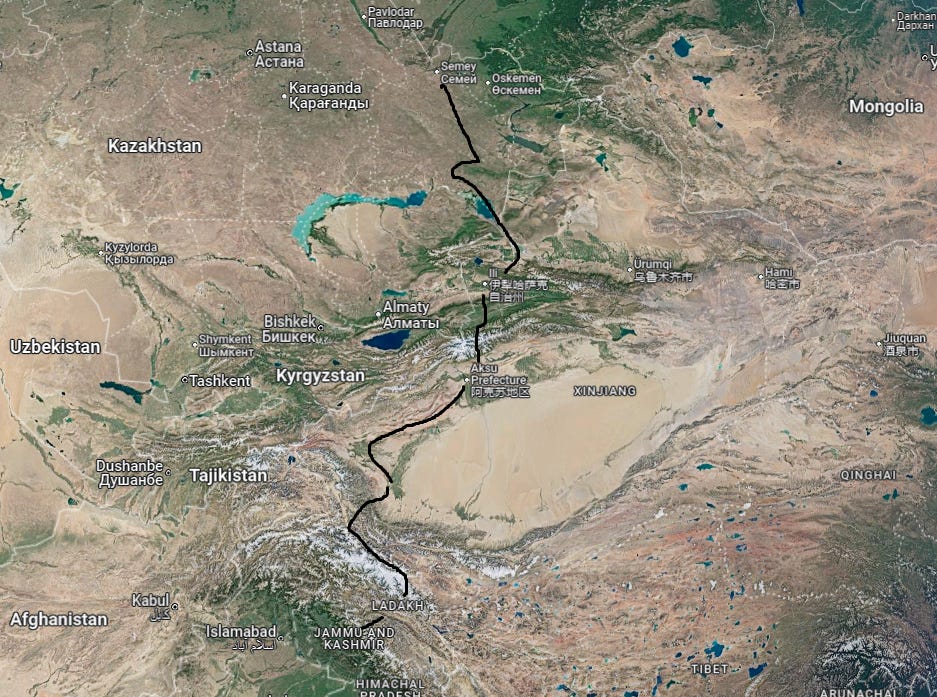

Rafailov first visited Russia in 1802 and returned in 1807. In February 1808 he went to Saint Petersburg to meet with Count Nikolai Rumyantsev, foreign minister of the Russian Empire. Rafailov was given financial support, and likely instructions regarding his mission ahead. On 4th August, 1808 he left Semipalatinsk (today known as Semey) with commercial goods bound for the Chinese frontier. His passport information is still held in Russian archives.

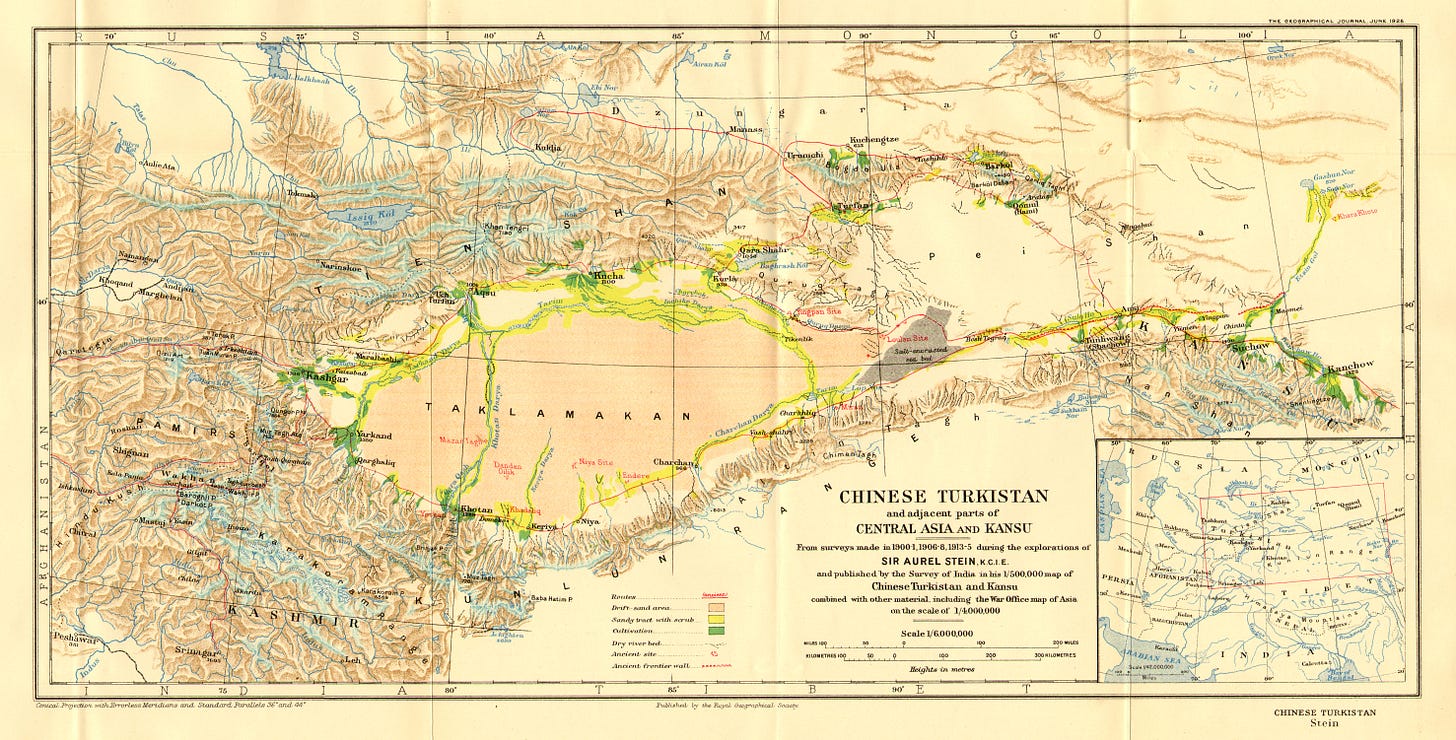

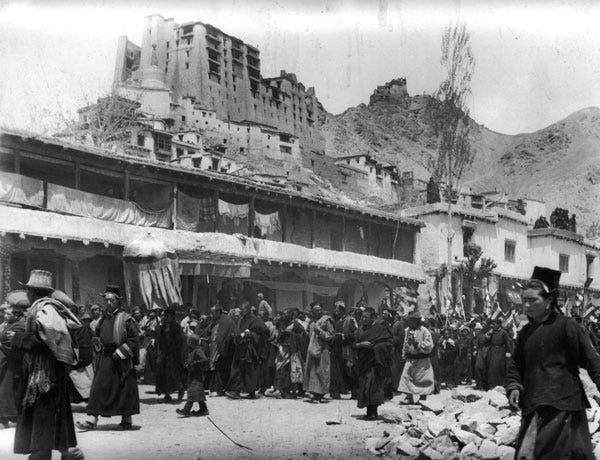

As Rafailov describes, he traveled from Semipalatinsk to Kuldja, known today Ili or Yining, in the Ili Valley. From there, he likely went over the Muzart Pass to Aksu in the Tarim Basin. He continued to Kashgar and Yarkent, two significant cities in the western end of the Tarim Basin from where trade routes lead to India and Trans-Oxania. His exact route after Yarkent becomes less clear, but he definitely did not visit Tibet itself. He likely visited Ladakh and mistakenly called it Tibet due to their culturally similarities. It is also unclear where exactly he visited in Kashmir, but presumably he reached Srinagar, the region’s largest city.

Rafailov returned to Semipalantinsk in 1811 and submitted his travel notes, which are translated below, to Commander of the Siberian Line Grigory Ivanovich Glazenap, who then forwarded them to Foreign Minister Rumyantsev.

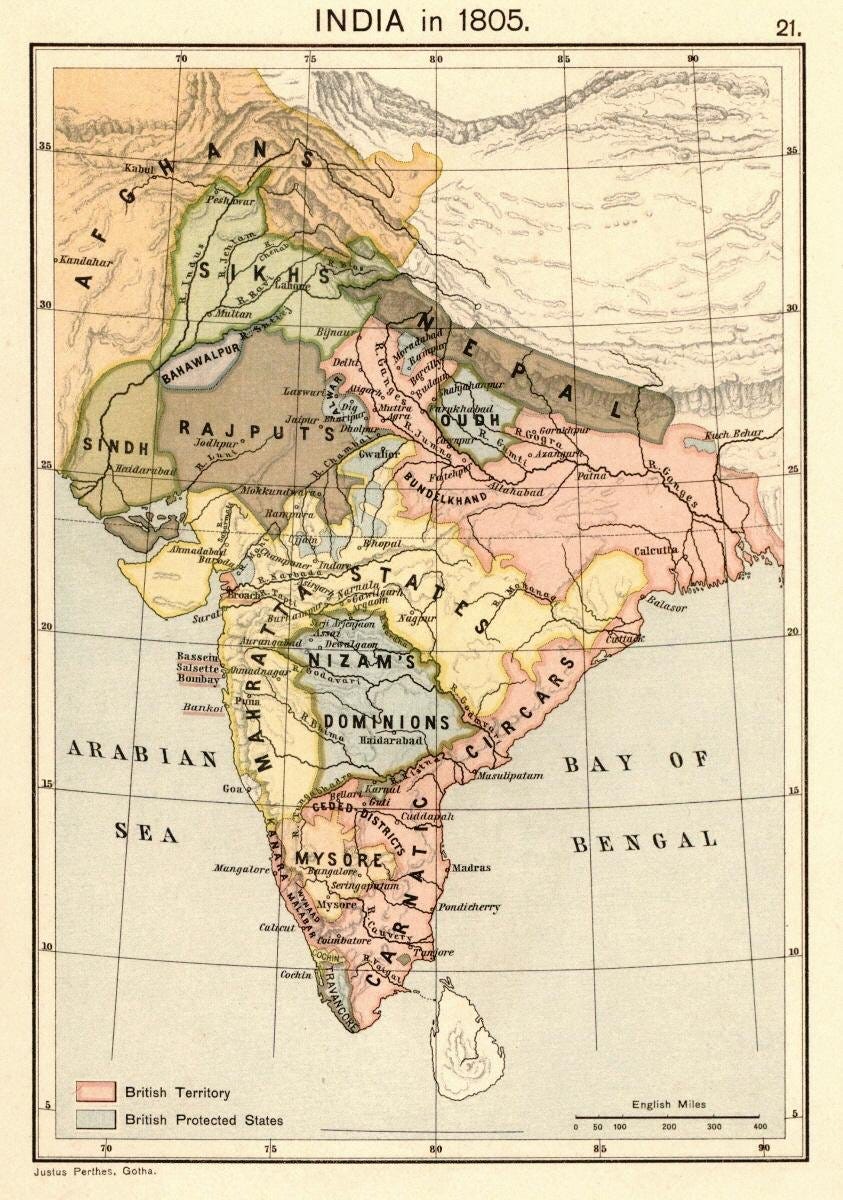

At the time, Rafailov’s report was a rare piece of detailed intelligence on countries that Russia knew very little about. Russia was particularly interested in opening up direct trade between itself and India. Russia’s interests were two fold. First, there was a great demand in Russia for Indian products such as dyes, textiles, incense, spices, sugars, varnishes, and especially raw cotton. Kashmiri shawls in particular had become fashionable among European aristocratic women following Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt. Russia was also dependent on cotton imports for its textile industry and hoped to purchase them directly from India instead of relying on English merchants who acted as middle men and inflated prices. Second, Russia hoped to become a transit hub for trade between India and Europe, which would have provided it with a great deal of wealth from custom duties on goods. This plan failed to materialize of course, largely because the distant from India to Russia is so great and overland trade could hardy compete with England’s stronger maritime ties to the subcontinent.

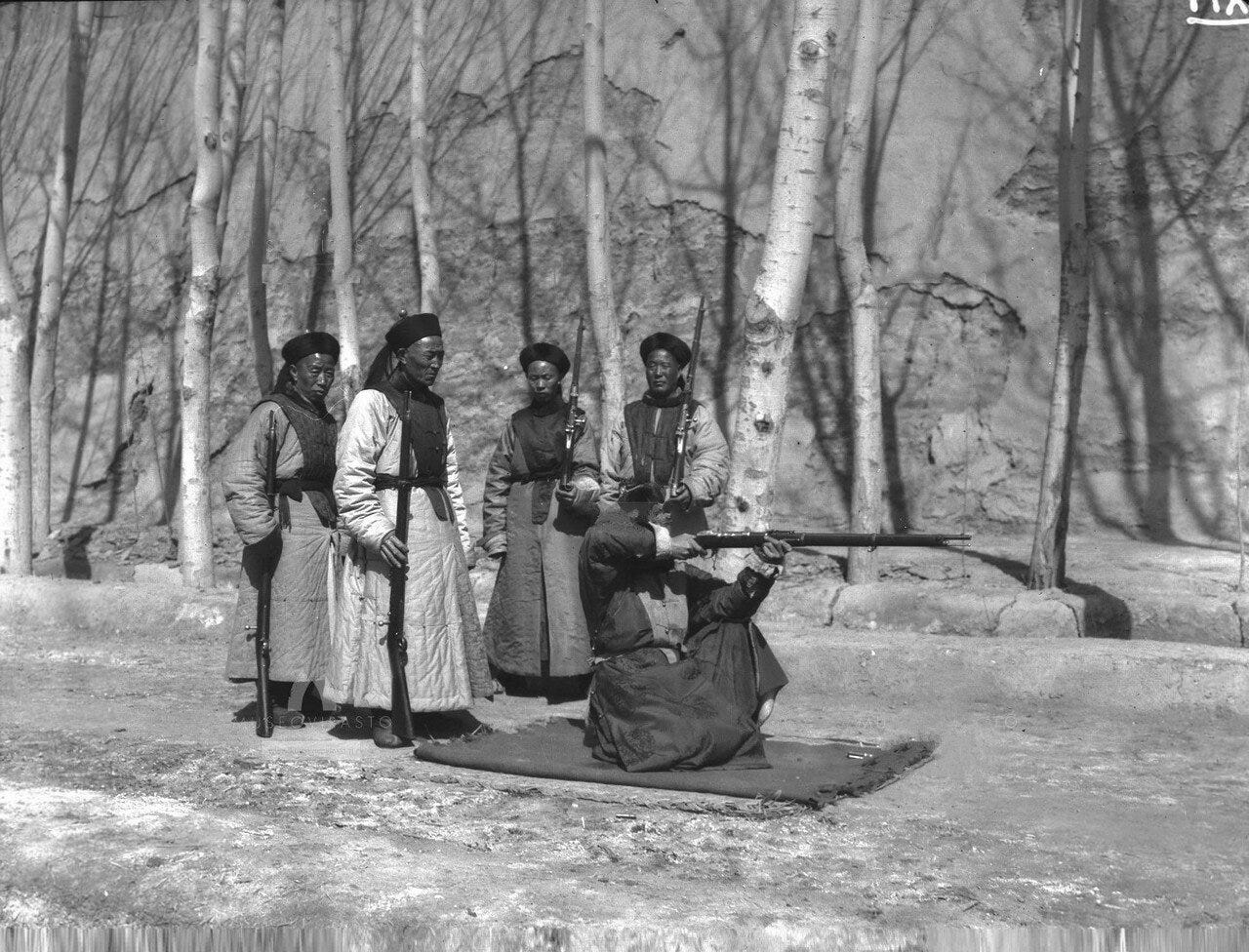

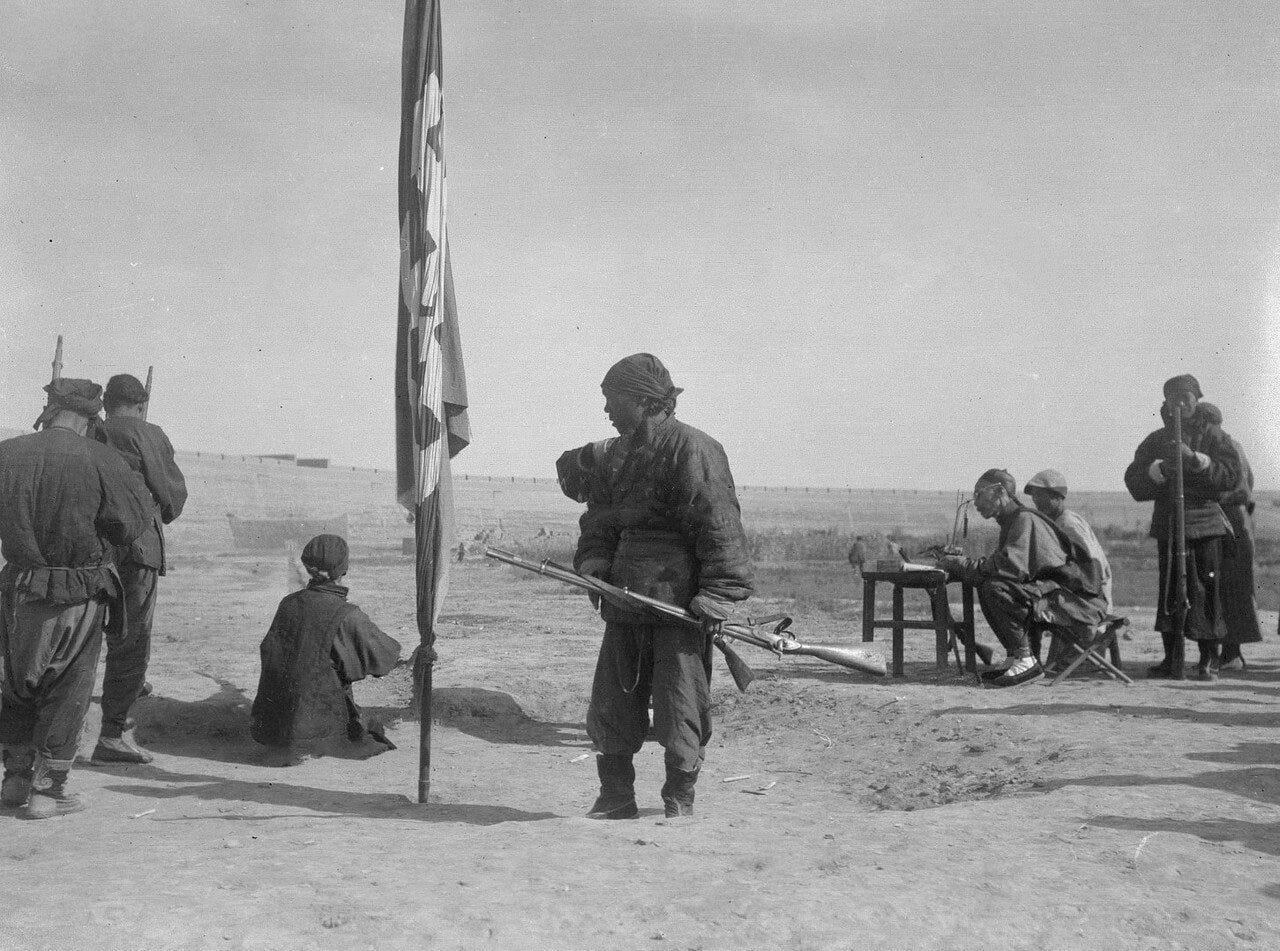

It is also evident from the Rafailov’s notes that his mission was more than purely commercial. Along with commercial information, Rafailov also details the number of forces stationed near each city, their strength, whether the cities are fortified are not, and local political conditions. Russia would naturally have wanted to learn about the state of Chinese military forces in Central Asia as the Qing Dynasty posed one of the biggest potential threat to Siberia, in addition to Chinese Turkestan being a potential target for further territorial expansion by Russia itself in the future. It is also not at all surprising that Rafailov served a spy, traveling merchants can easily collection information about the foreign countries they do business in. It is also true that the same routes that caravans carrying trade travel along also serve as roads for armies.

Upon returning to Russia in 1811 Rafailov was rewarded a golden medal with the inscription “For being of use”1 that was attached to the red ribbon.

In 1812 Rafailov submitted a document titled “Project for opening routes, which lead from Russia to India” to Foreign Minister Rumyanetsv for consideration. This text is significantly longer than his notes that were submitted in 1811, and also rely on observations and data he collected during his travels. I plan to translate and publish this document as well sometime in the future.

In 1813 Rafailov set out for Western China again, this time with a letter from the Russian state addressed to the ruler of Tibet (also likely a reference to Ladakh). During this trip Rafailov visited many of the same places that he traveled to in 1808-1811, in addition to Issyk-Kul in the Tianshan Mountains. Upon returning back to Russia, Rafailov was given the rank of court advisor in 1819, which was probably connected to his alleged conversion to Orthodoxy as reported by Moorocroft. On his next mission he was asked to purchase six Turkmen stallions for state stud farms and to purchase Tibet goats, which Russia hoped to breed in Siberia.

On 30th April, 1820, Rafailov departed Semipalatinsk for what would become his final mission. Disguised once again as a merchant, he was tasked with delivering two letters from Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode, one to “the owner of the Punjab regions, Ranjit Dsing” and an other to the ruler of Kashmir, Ranjet Akibet. The letter to Ranjit Singh in particular proposed that the Punjab and Russia establish friendly relations and that their merchants could travel freely to each other’s territories. Travelling first to Turfan, he continued to Aksu and then on to Yarkent. On the road just before Yarkent he suddenly fell ill and died a few days later, while according to Moorcroft the story differs. According to him Rafailov was murdered by his travelling companions somewhere in the Karakorum Mountains, the range that separates the Tarim Basin from India.

What makes Rafailov’s death so curious is that the letter addressed to the Maharaja of the Punjab Ranjit Singh ended up in Moorcroft’s hands. Considering these facts, in addition to Moorcroft’s role as an intelligence agent, it is fully possible that Rafailov was poisoned or assassinated on the orders of English intelligence, possibly by Moorcroft himself, who aimed to prevent Russia from establishing diplomatic contact with the Sikh Empire, which at the time was independent.

This was the era of the “Great Game”, the great imperial rivalry between Russia and Great Britain for mastery of Inner Asia. The rivalry was triggered by British fears that Russia would attempt to invade India following the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit where Tsar Alexander I allied himself to Napoleon. British fears only mounted as Russia in the following years expanded deeper into the Caucasus and northern Persia. By the 1880’s Russia and Britain came to the brink of war, following Russia’s annexation of the Pandjeh oasis on the Afghan frontier. The British concern regarding Rafailov was likely that Russia might seek to turn the Sikh Empire into a barrier preventing any further British advance to into northwestern India, in addition to expanding their own commercial reach at Britain’s expense.

A definite explanation as to what happened to Rafailov would require additional research. Maybe sometime in the future I will write a short follow up to this post that examines this question more closely.

For related texts, see “Beyond Three Seas” by Afanasy Nikitin, the first written account of India by a Russian, and Notes of Chuguchak by Andrei Putintsev, another espionage report written by someone who visited Western China under the cover of a commerical mission. Concerning the aforementioned war scare in the 1880’s, see a Russian report on the defences of Herat.

Testimony of the Kabul Resident Mehdi Rafailov, Who Left from the Frontiers, Sent by the Minister of Foreign Affairs

On 1808 August 4, from the fortress of Semipalatinsk1 a journey was undertaken to Kuldja,2 the first of the nearest Chinese frontier towns.

From Semipalatinsk across the Kyrgyz3 steppe and the Tarbagatai Mountains I reached Kuldja with a caravan, after having left the fortress 45 days prior. Up to the Tarbagatai Mountains the region is flat, there are no large forests, but finding firewood is not difficult for caravans, and there are no waterless or sandy places. Crossing the Tarbagatai Mountains on a straight route is impossible even on a loaded horse due the mountains’ extreme height, and they avoid this obstacle by going around them through a different mountain, named Khamar Taban (cape of the mountain), from the midday day side, where the path is very easy. And some of them reach Kuldja from Semipalatinsk by cart without having to make any stops, having avoided the obstructing Tarbagatai by going along the slopes of the mountain Khamar Taban (a detour of 50 verstas4), and from Semipalatinsk to the town of Kulja I assume it is no more than 900 Russian verstas.

Notes on the City of Kulja

Upon arriving to Kulja I appeared under the name of a Tashkenti, as the Chinese do not accept those who come from the Russian frontier for trade. And even bartering is only done with Asians there, and most of all with Kyrgyz, from whom they receive various cattle for their goods. Duties on caravans arriving here are not collected, and customs do not exist, as trade in this town is carried out by the state. Kuldja cannot be called a commercial town. Its residents consist only of Mohammedans, as this town was not formerly Chinese, but was conquered by them no more than 60 years ago from the Tatars who now inhabit it. The leaders of these conquered Mohammedans are of the same nation, as in the towns of Aksu, Kashgar, Yarkent and in others.5 But only minor affairs can be decided without the military governor or a Chinese official, nor can they even begin to consider it. Their role is only to keep peace and order, and reporting daily on this to the military governor or to the official in charge of them. These Mohammedans have received the name Tarachi (farmer). The treasury distributes various type of grain seeds to them which they sow and harvest, and then deliver the food supplies to the forces who hold the frontier, and to the fortress Kure,6 which is 30 verstas away from Kuldja, where the governor is located and where trade is carried out, but not in Kuldja itself. This fortress is surrounded by a stone wall.

At Kuldja there are quite a number of Chinese merchants, they are called Kara Chinese (Black Chinese),7 and their main income comes from production and trade.

Their forces are made up of Manchus, Kara Chinese and Dunguns, as well as Kalmyks and Mongols.8

The Manchus are like nobles that serve as officers and they are rewarded according to degrees with ranks and they are accompanied by civilian officials. Their head commander is the amban,10 and the military governor is the Zangzhun.11 No more than 22,000 troops can be positioned there. These forces, as we managed to see during the 4 months we stayed there, were trained in the military arts, but it does not extend further than shooting a bow while on horseback and on foot. Their canons are in a very weak position, without carriages, on two wheels, and are barely suitable for action. In Kure, there are no more than 10,000 houses, and in Kuldja no more than 2500, where there are also suburbs, and up to 50 Dungun homes.

About the City of Aksu and its Region

After living there for 4 months I asked to military governor for a pass to visit Kashgar, with the explanation that my parents are located there. At first I was denied this under the pretext that passes to visit there are strictly forbidden. However with some expenses I was issued a passport to go there by the governor, after which I then departed for Aksu, which I reached with pack horses after 14 days. This route is inhabited by different peoples, such as: Chinese, Kalmyks and Mohammedans, and they called the latter Erliks (ancient inhabitants of this land). Their villages consist of no more than 25-30 homes. And the Kalmyks lead nomadic lives, of which there is a significant number, and in every village or station there are military teams. These peoples are usually engaged in cattle breeding. While they do produce grain, it is very minimal. On the route from Kuldja there are 4 factories, which produce copper, iron and cast iron.9 The workers are mostly slaves, exiled from the interior of China for committing crimes.

The soil of this land is good, suitable for growing grain. There is an abundance of grass and forests, timber and coniferous. The locality is flat, except for one set of mountains that lie in the middle of the route, named Muzdaban (Icy Mountain). The path going through it is steep and not without significant difficulty, but passing over it requires no more than a day, and this is on a pack horse. Travelling on camels is impossible. They go around this obstacle to its right side and avoid it without any difficult; but why following the more convenient route is forbidden is unknown; guards are kept there in case of this. The peaks of these mountains are covered with eternal snow, which during winter time in some places piles more than 100 arshins10 thick, and in summer up to half of it melts. An amban is located in the city of Aksu, which manages military and civilian affairs. The town has no more than 6000 homes, none of which are fortified. A customs office has been established here, charging a duty on all the peoples who flock here from the most distant countries for trade, such as the Chinese and their subjects, the Tunguts and Kashgaris, and the Tashkentis, Bukharans, Kashmiri, Indians and wild Kyrgyz11 who all arrive here from cities in the interior of China. A duty of one piece or thing is taken from every 30 pieces or things, and equally so from herds of cattle. From Kashmiris in respect to their significant trade here, only one item is taken from every 41 items.12

The amban resides outside of the town in a special suburb, which is also not fortified, called Gulbak. There is a force of 3000 men there. And in the city itself is also an official, similar as the one at Kuldja. The city is mostly populated by Mohammedans, who are engaged in trade, agriculture and gardening. There are few significant merchants among the residents. These people are also engaged in the production of a particular type of paper material under the name of byaz,16 or as is locally called, bumaz. The city itself is poor, but from the flow of merchants to said place, trade is significant and uninterrupted. I lived here for 40 days. I did not purchase any good, but saved up gold and silver. From here I reached Kashgar, which I reached after 12 days and through 12 stations.

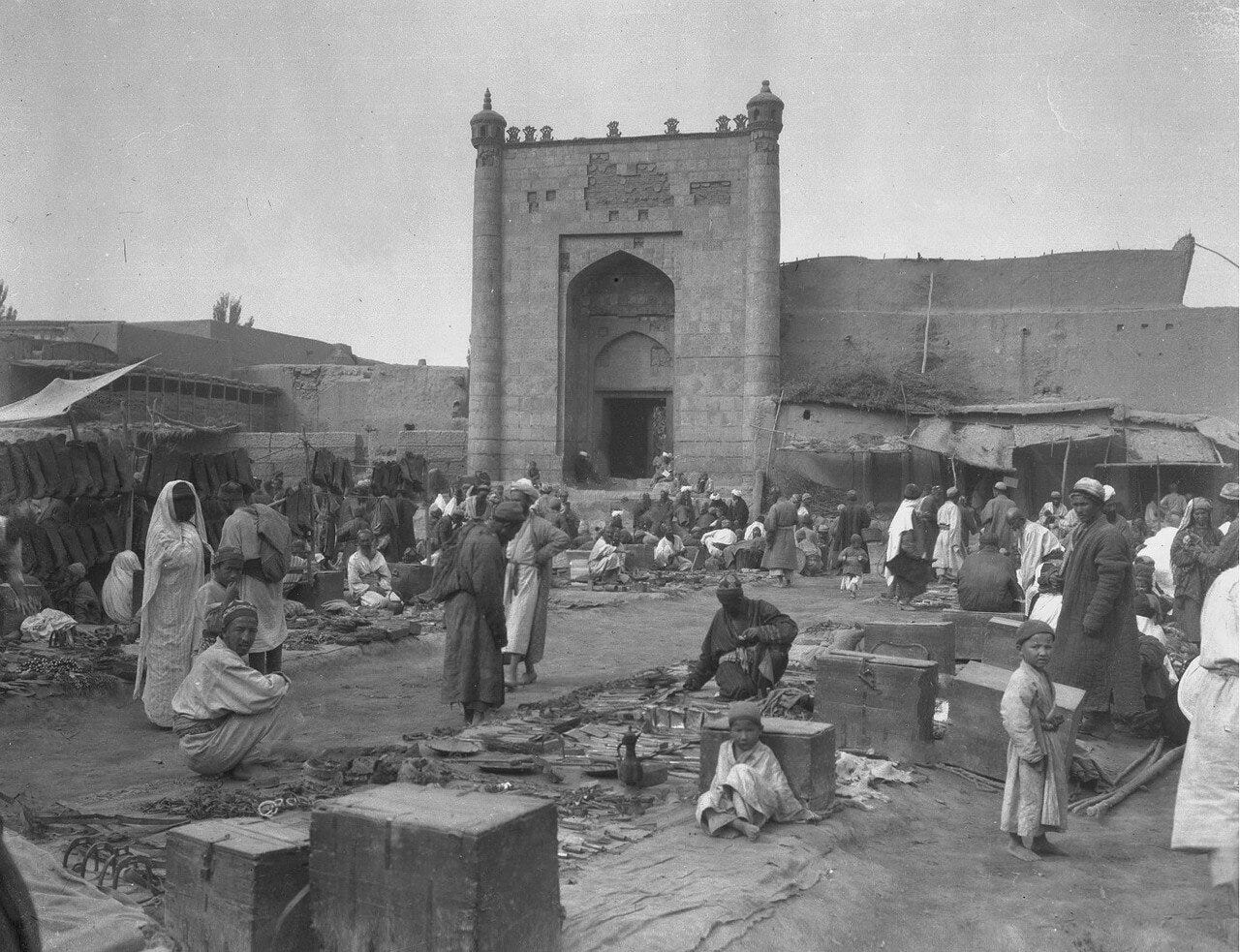

The City of Kashgar and its Surroundings

Kashgar is generally populated by Mohammedans. Chinese however keep a guard of 20 people at each station, in a locality that is very flat and abundant with lands, such as: forests, grass, gardens and agricultural fields. There are no waterless places, and the rivers, although not as great as those between Kuldja and Aksu, it is impossible to go across them without a boat. They flow from the mountains, which extend from the Tarbagatai range, and they flow all the way to Kashmir and beyond.

Kashgar is a significant town, its residents are plentiful, there are quite a number of merchants, its commerce is in a most flourishing state, it is a major gathering place of people, customs are in a similar position as in Aksu. Judging by the extensive trade, the income from custom duties is incomparably larger than in Aksu. Residents in this city are also in large part Mohammedans. It has more than 6000 homes. The city is surrounded by a wall made from unfired bricks, but it is not very durable. There are two officials, the military one is the zhangzhun, and the civilian one is the amban. The forces under the command of both are no more than 10,000 men. These officials live outside the city in a special fortress, fortified, like the city, by a single wall. The forces are located in the city and in the surrounding villages. The art of their military craft is not any different from the above mentioned forces. There are quite a few factories which produce paper byaz, that being bumaz - a paper good, a little better than bumaz, and half silken materials of the best quality. Grain production and gardening is in a flourishing state. I lived 2 months here, and having shown that I have relatives in Yarkent, I received another passport.

The City of Yarkent

They reach the city of Yarkent in 4 days across 7 stations. Between these cities at a distance from Kashgar of 50 verstas lies a fortress, named Yagi-sar. There is an amban official here. The forces he has with him are up to 600 men. Mohammedans nomadize in the surrounding areas here. Their occupation is cattle breeding and agriculture, and gardening to a lesser extent. The locality is flat, grass is abundant, there are no forests except for the willows that grow along the rivers. There are no waterless and sandy places. The people who inhabit the stations and who nomadize, ever since China conquered them by force of arms, have been in a state of extreme enslavement, which causes them to be very poor. The city of Yarkent is average in wealth, but the gathering of commercial peoples, as in the first cities, is incomparably greater than in Kashgar, and the custom duties are considerable. This city is fortified similar to Kashgar. There is one official, the amban, who is also in a special fortress and is positioned similarly as in Aksu. There are up to 12,000 homes here. Production is similar as in the previously mentioned cities. There are 4500 soldiers in this city. I lived here for 40 days. The forces stationed in these places are to observe the aforementioned conquered peoples, so that, as all the Mohammedans, they cannot rebel and overthrow the Chinese yoke. The Chinese possessions end here.

The Tibetan Possessions

Having made a petition in Yarket for a pass, I went to Tibet, which I reached in 34 days. Starting from Yarkent, for a distance of 100 verstas the land is flat, and from here are the Karakum Mountains (Black Rock), Muz-daban (Icy Mountains), Karaul-daban (Mountain- piket), Aktau (White Mountain), Karatau (Black Mountain) and Kyzyl-tau (Red Mountain).13 These mountains are extremely tall, so that on some lies eternal snow. Forests, although they do have them, are small, growing along rivers, and they are encountered two or three times a day. There is almost no grass at all, and thus travelers carry with them oats and barley for their horses. The mountains extend all the way to Tibet. Between these cities there are no peoples. The city of Tibet does not depend on anyone. The Tibetan people generally all follow pagan law. The ruler of Tibet is the rajah (the word rajah means ruler or khan). There are few villages around this city, agriculture is also very minimal because the earth is not fruitful, the soil is stony, the air is heavy and harmful, which, according to my observations, makes the people weak and appear as if exhausted, as their faces are entirely without colour, and even they acknowledge that the climate they inhabit is unhealthy.

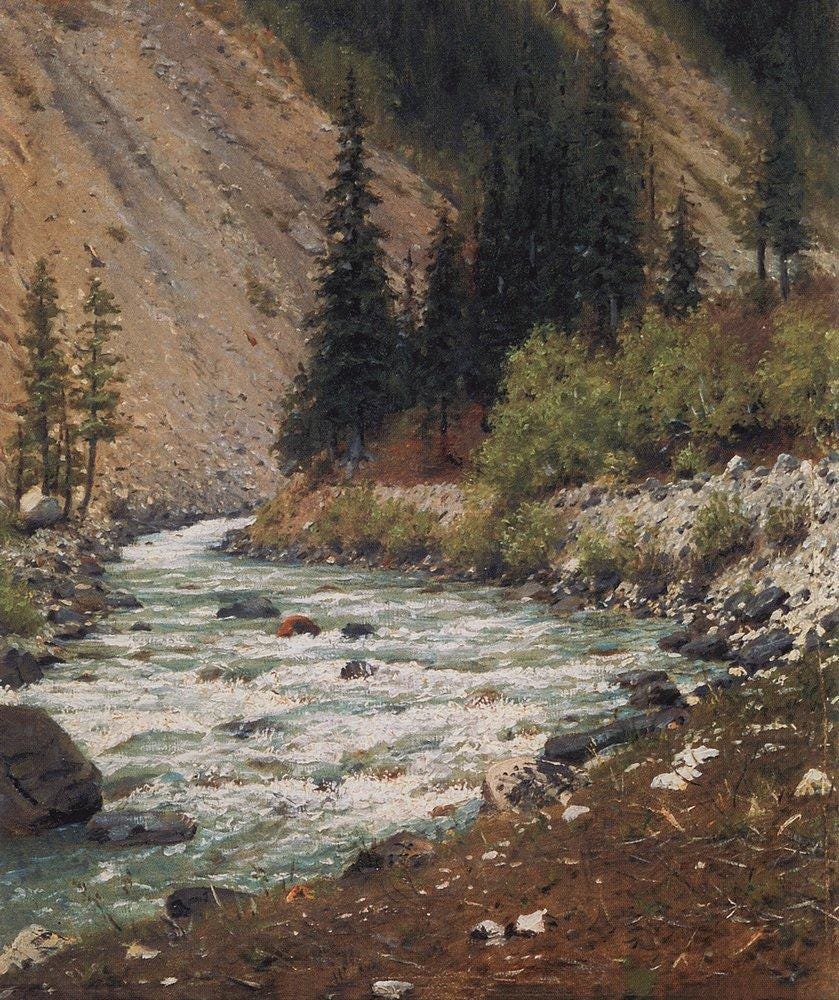

This city is in a very poor state. One of the only things supporting them is that precious wool is exported from Tibet to Kashmir, and equally they collect income from merchants who pass through their land from Kashmir, Lhasa, Yarkent and India. Residents of Kashmir purchase the wool for shawls. The amount of wool exported in a year is up to 7000 poods. The Tibetans levy duties on merchants passing through their city, and private people often maintain homes for them. The people are not warlike and do not even have an understanding of forces. I stayed here for 8 days, and having received from the authorities a passport, I headed to Kashmir. I reached it in 17 days. There are 17 villages on the route between these cities. The residents of this country up to the small town of Drast belong to Tibet. From Drast I traveled for 3 days to Kashmir, and on this stretch the peoples already belonged to Kashmir. The inhabitants in these places are generally in a poor state, engaged for the most part in cattle breeding and agriculture. These towns have from 20 to 30 homes. From Tibet to Kashmir itself the places are mountainous, forested, arable and abundant in gardening.

The City of Kashmir

Although this city is considered to be under the rule of Augan,14 but the leader of this city has little respect for the Augan ruler. The tribute imposed upon it is 5,000,000 rubles and is currently not being given to the Augans because of the civil strife that has broke out among Augans.

Kashmir is divided by the river Vernak into two parts. This city has many people. It has up to 100,000 homes, including 20,000 homes of people who follow Indian law. Homes are small, occupied by one part of a family and cannot not be compared to homes in European cities. The people who congegrate here is extraordinary and from varied powers, such as; from Turkey, from Persia, from India, from Augan, from Yarkent and Bukhara. In this city there are up to 20,000 machines for making shawls and other goods. This significant production brings the government up to 1,200,000 rubles of income. Along with this, the region is abundant in the best degree of all kinds of growth; they are engaged in agriculture and gardening to a great extent, and harvests of sarach millet are especially superior and incomparable to other places in the province.

The city does not have any sort of fortifications except for suburbs, which are occupied by the rulers of this city and are surrounded by a stone wall, forces are located in this city and in surrounding villages, which are thought of to be cavalry of 10,000 to 12,000 and infantry from 8,000 to 10,000 men. They are armed with firearms, but the guns they have are of the Asiatic manner local to the province, without locks and wicks. The Kashmiris, except for the Indians, generally follow Mohammedan law. The city and region of Kashmir is surrounded by high mountains. The people of this country are beautiful, healthy, cunning and enterprising. However, while hospitable, they not have any metallurgical factories. The authorities of this city collect duties in the form of money on shawls that foreign merchants both bring in and carry out of their frontiers. There is no duty on gold and silver.16

On my return trip to the Russian frontiers from Kashmir I went through the same cities which have already been discussed here.

Semipalatinsk was founded in 1718 and became Russia’s main commercial hub with Central Asia and the steppes in the east

Also known historically as Guldja. Known today as Yining or simply as Ili

Actually Kazakh. Prior to the Soviet period Kazakhs were called Kyrgyz

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 versta = 1.0668 km/3,500 ft

Note made by Rafailov: According to legend, the residents of these towns are sinply known as Tatars, left there by Chingis Khan, who once possessed Siberia

Note made by Rafailov: Our merchants consider the Kuren fortress to be a part of Kuldja, which in general they call Kuldja

Unclear who this refers to

Kalmyks are western Mongols, related to the Zungars

The original word is “цугун”

Old Russian unit of measurement. 1 arshin = 71.12 cm/2.33 ft

This is likely a reference to the people who are today called Kyrgyz. During the 19th century they were often referred to as Wild-stone Kyrgyz

The meaning of this passage is very ambiguous, but I think it refers to the amount of goods that is taken as the duty. The original say: “С 30-ти штук или вещей - одну вещь, равным образом со скота с 30-ти одну ж, а с кашемирцев в уважение значительной их торговли - с 41 -й штуку одну же.”

These are all Turkic words

I think its refers to Afghanistan