The Russian Expeditions to the Golden Lake and the Conquest of the Altai Mountains

The History of the Cossack Expeditions to Lake Teletskoye and the Exploration of the Ob River Basin, 1609-1674

Preliminary note: For Gmail readers, this essay might be clipped due to size limitations. To read the entire essay simply click on “View entire message” at the bottom of the email, thanks.

Introduction

In the very heart of the Altai Mountains, nearly half a kilometer above sea level, lies the Golden Lake. Surrounded by cliffs covered in thick Siberian forests that tower all around, the lake sits in a large alpine valley 78 kilometers long and up to 5 kilometers wide, and reaching a depth 100 meters in some places.1 The cliffs decline sharply down to the water’s edge, often leaving little to no flat terrain between the mountains and water. Only a few small capes and flat pieces of land dot the otherwise mountainous shoreline. More numerous are the waterfalls that ferry the melted snow and ice from the distant glaciers and eternally snowcapped peaks into the lake. In all, more than 70 rivers drain into the lake, with the largest being the Chulyshman which flows into the lake’s southwest end. The valley of Chulyshman is a narrow gorge that only widens and opens up at the mouth of the river. At the top of the Chulyshman valley is the Katu-Yaryk Pass, which leads to the Chui steppe on the far of the Altai range, and beyond that the Mongolian plateau further still. At the northern end, the lake is drained by the Biya River, which carves its way down through the mountains to the south Siberian steppes. Past the Altai foothills in the lowland steppes, the Biya merges with the Katun River whose head waters also lie in the Altai Mountains to the west, and together they form the Ob, one of the great rivers of Siberia. Further downstream the Ob is joined by the Irtysh, whose headwaters lie in the southern Altai region near the modern Chinese-Mongolian border. Together, they continue flowing south to the Kara Sea and the Arctic Ocean.

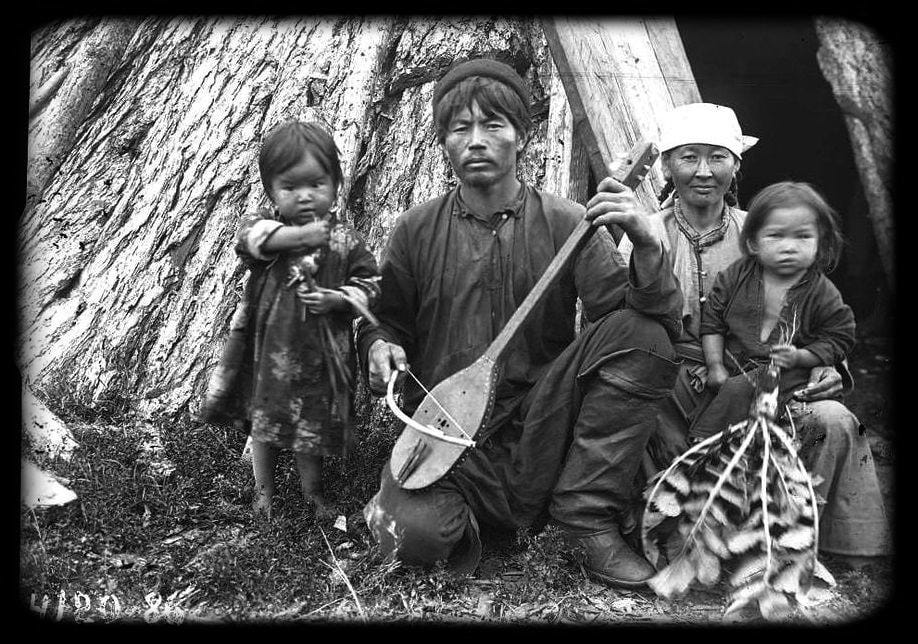

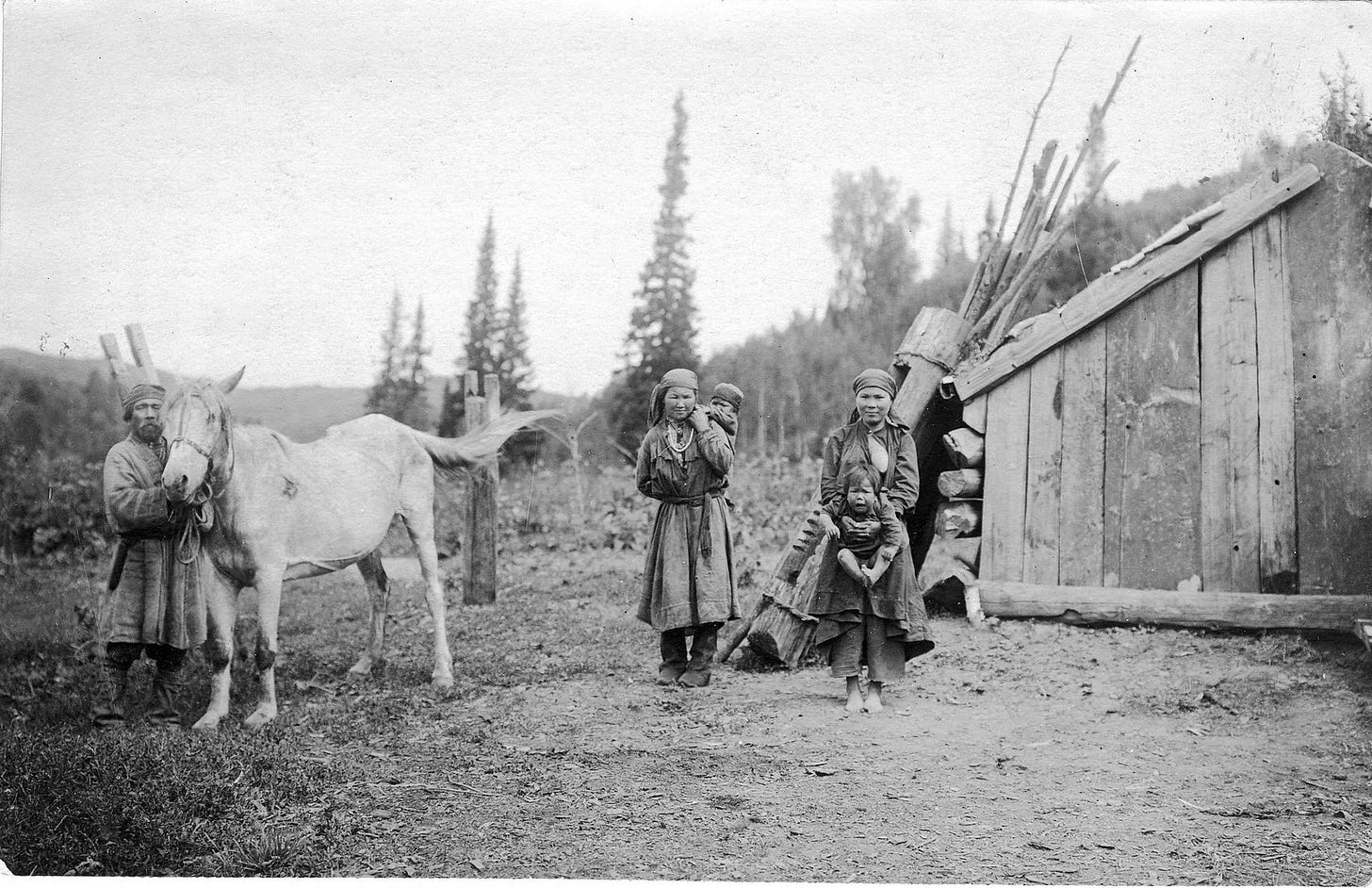

In the folk tales of the Teles, the people who inhabit the lake’s shores and live along the Chulyshman, the valley of the lake was created when the sword of a mighty khan fell from its sheath and struck the earth upon the khan’s death by treachery. As the sword struck the earth an abyss was formed, and the tears of the khan’s beloved filled the canyon with water. Other folk tales speak of people finding pieces of gold around the lake. These stories often tell of people, those either lost in the forests searching for a way out or others starving in search of food, only to stumble upon a gold nugget. At first they are relieved, the gold is of great value and they hope it will solve whatever problem they have. But as they wander on in search of home or food, they realize the gold itself is of no use and bitterly they cast it into the lake. From this comes its name, the Golden Lake, or Altyn Kol in the language of the local Teles people.

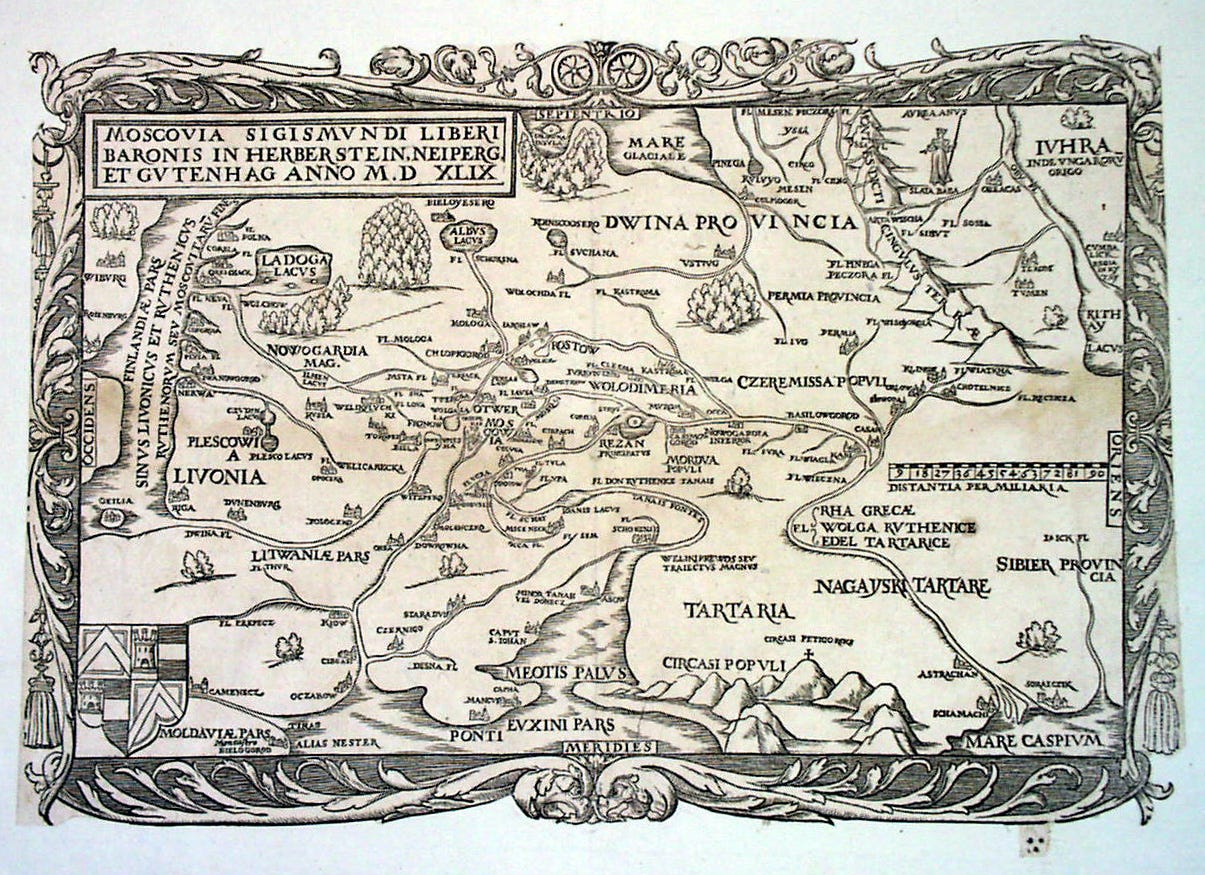

Since at least the 16th century, when the borders of Muscovy were still constrained by the nomadic hordes on the steppes and the Cossacks had not yet ventured into Siberia, the Russians have had some inkling of knowledge of this hidden lake far in the depths of Asia. On the map of the Moscow state published in 1549 by Sigismund von Herberstein, a diplomat from the Holy Roman Empire who traveled to Muscovy and was one of the first Europeans to write about Russia, a curiously labeled “Kithay Lacus”, Latin for “Chinese Lake,” can be found in the top right corner, and is shown to be the source of the Ob River which flows north. Later European cartographers relied on Herberstein’s map for information regarding Siberia and other regions of Inner Asia.2 This “Kithay Lacus” was later found on maps made by Gerardus Mercator and Jadocus Hondius from the turn of the 17th century. The latter labeled the lake as belonging to the “Kara Kithay,” in reference to the Kara Khitan, also known as the Western Liao, a state based in Central Asia from the 12th to 13th centuries that had was created by Khitan forces who fled westward as their state in China collapsed from the onslaught by the Jurchens of the Jin Dynasty. The Khitan were a semi-nomadic tribe from southern Manchuria, and would be the source of the Russian word for China –Kitai.

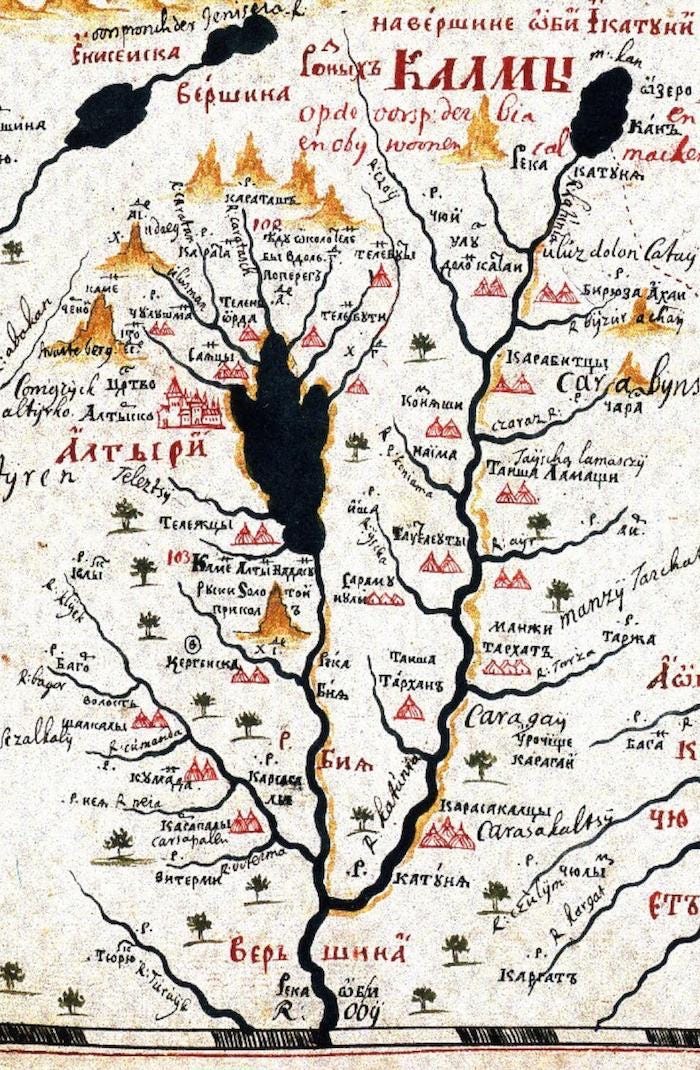

A century later, this “Chinese Lake” reappeared on a map of Tartary by Nicolaes Witsen, this time named as Altin, the Mongolian word for Golden. A “Cathay Lacus” is also found on the map of Russia by Anthony Jenkinson, an English explorer who in the service of Tsar Ivan the Terrible explored the Caspian Sea and routes to Persia in the latter half of the 16th century.3 This “Chinese Lake” only appeared on Russian maps in the late 17th century during the reign of Peter the Great. First found on maps made by Semyon Remezov, a Russian cartographer of Siberia based in Tobolsk, then the capital of Siberia, the lake is said to be only a 6 day journey on horseback from Kuznetsk.4

Once properly discovered and visited, the lake became known to the Russians as Teletskoye, named after the Teles people who are now known today as Telengits and speak a Turkic language. In the words of Johann Eberhard Fischer, a native of Bavaria and a pioneer in Siberian history who wrote on Russia’s expansion using primary sources from local Siberian archives, the origin of the name was such: “The lake, which the above mentioned river flows from, is called the Altyn-Nor according to the Kalmyk language, in other words, the Golden Lake. A Tatar tribe lived there, named the Teles: and according to this the Russians named the above mentioned lake Telessky.”5 As the crown jewel of the Altai Mountain, itself also meaning “golden”, Altyn-Kol was suitably named.

The Altai Mountains have long been rich a source gold. The early Scythians found their gold in the Altai Mountains and used it to create their famous animal jewelry, and their mines have been discovered around Zmeinogorsk, Zyryanovsk and elsewhere. While the Teles would occasionally found gold around its shore, the lake’s true wealth lies with the animals and game that live around it. The abundance of elk, deer, foxes, sable, birds, its waters full of fish make the lake into an Eden hidden away within the high Altai Mountains.6 While gold and other precious metals would later draw Russian attention, at least initially, the riches they sought in the Altai Mountains were furs.

Just as Jason and Argonauts were the first Greeks to visit the Black Sea and open it up to colonization, it was in pursuit of their own “golden fleece” that first attracted the Russians to Siberia at the end of the 16th century. By the end of the 17th century they had reached the shores of the Pacific Ocean and northern frontiers of China. It was likewise these animals and their furs that drew the Russians to Lake Teletskoye. Throughout the 17th century the lake was the target of several expeditions by adventurous and predatory Russians who overcame the harsh Siberia taiga in order to reach it. For each of these expeditions the purpose was straightforward: to defeat the Teles and to subjugate them “under the high land of the Russian Sovereign”, and most importantly, to collect furs from them as tribute. The export of these furs, similar to oil and gas in the modern industrial world, brought windfall profits to the Russian state as they were sold to markets in Europe, the Islamic World, India and China. The wealth from its fur trade fueled further expansion and strengthening of the Russian state, which in the end turned into one of the leading states of the world, a status which it was retained to this day. And without its early wealth from furs, none of this would have been possible.

These expeditions also served a duel propose. Not only were the Russians in search of furs, they sought new lands to colonize and new trade routes that would connect them lucrative markets, especially those in China, which lay beyond the steppes to the south. During the initial expansion into Siberia the Russians pushed out as far as these could until either geography or armed resistance halted them. The Russians soon met such resistance in the lowlands and foothills north of Altai Mountains. Upon hitting a hard limit to their expansion, the Russians then sought to create a secure frontier for their state in southern Siberia. Consolidating control over the Altai Mountains was especially crucial in this process for two reasons. First, the head waters of the Ob River, whose drainage basin covers the entirely of western and much of central Siberia, have their origins in the Altai Mountains. Second, the tall, nearly impassable mountains functioned as a hard physical barrier between Siberia and the hostile nomads on the steppe. By consolidating its power over the Altai Mountains, Russia would by extension cement its hold over Siberia and ensure its security from the nomads on the steppe, and later, the Chinese Empire. This task was only completed during the reigns of Peter the Great and his successors in the 18th century, but the foundations were initially laid in the previous century. While the expeditions to Lake Teletskoye were only relatively minor episodes in Russia’s conquest of Siberia, they were critical conquering the Altai Mountains and creating what later imperial writers would call Russia’s “natural frontiers.”

Russia’s Expansion into Siberia

Peter the Great, who rose to power on the eve of the 18th century, is often credited with laying the basis of Russian power. As is commonly believed, Russia prior to Peter was a backwards, half oriental tyranny, still languishing from the Mongol conquests, and only thanks to his Westernizing reforms was Russia brought in line with the Great Powers of Europe. While not entirely wrong, this narrative is mistaken in who it praises. Aside from it obviously being a narrative that flatters the West, and unsurprisingly is favoured by Western historians of Russia, it entirely overlooks what Peter inherited upon ascending to the Russian throne and what made his Westernizing program at all possible. What made Peter’s reforms possible, and what truly laid the basis for Russia’s power down to our day, were the lands and resources conquered by Tsar Ivan IV, better known as Ivan the Terrible.

The epithet “Grozny”, often mistranslated as “Terrible”, is more accurately translated into English as “Formidable.” Whether intentional or not, this mistranslation has served to highlight the more tyrannical aspects of Ivan IV’s reign at the expense of his enormous achievements, namely the conquests of the Volga and Siberian Khanates.

By the mid-16th century the once mighty Golden Horde that had in the past reigned over Russia had already fragmented into several smaller successor states. On the Volga was the Kazan Khanate located to the west of Moscow, and in the Volga’s delta was the less powerful Astrakhan Khanate. The most powerful of the successor states was the Crimean Khanate with its capital at Bakhchisarai, who could mobilize 80,000 cavalry and as late as the 18th century remained a formidable threat, in large part thanks to its relationship with the Ottoman Empire.7 Beyond the Ural Mountains was the Khanate of Sibir, whose capital was Qashliq lay the Irtysh River. In the steppes was the Nogay Horde, a highly fragmentary grouping of nomadic tribes which soon splintered in various directions. With modernized firearms and cannons, Tsar Ivan IV conquered Kazan in 1552 and Astrakhan in 1558, which opened the Volga and its entire drainage basin for unhindered Russian navigation. Russian ships were then able to sail down into the Caspian Sea, to the Caucasus and further still to Persia. Yet more consequential for the time being, the Russians were now sail up the Kama River, a tributary of the Volga which enters it just below Kazan and whose course runs parallel with the Ural Mountains. As many of the Kama’s tributary streams flow down from the Urals, the gates to Siberia were now open to Moscow.

The lands around the Kama were soon acquired by the Stroganov family, a powerful mercantile clan whose wealth lay primarily in the salt trade. The Stroganovs eventually began trading their salt for furs, which they began exporting to markets overseas. Coinciding with Moscow’s conquest of the Volga basin, English traders opened up the Arctic Sea route to Russian and began visiting Archangelsk on the White Sea.8 The Stroganovs soon saw an opportunity: the furs of that great endless expanse of land beyond the Urals could be harvested and exported across Europe and the Near East for immense profits. But before this, Moscow’s sovereignty and control would need to be extended over Siberia first.

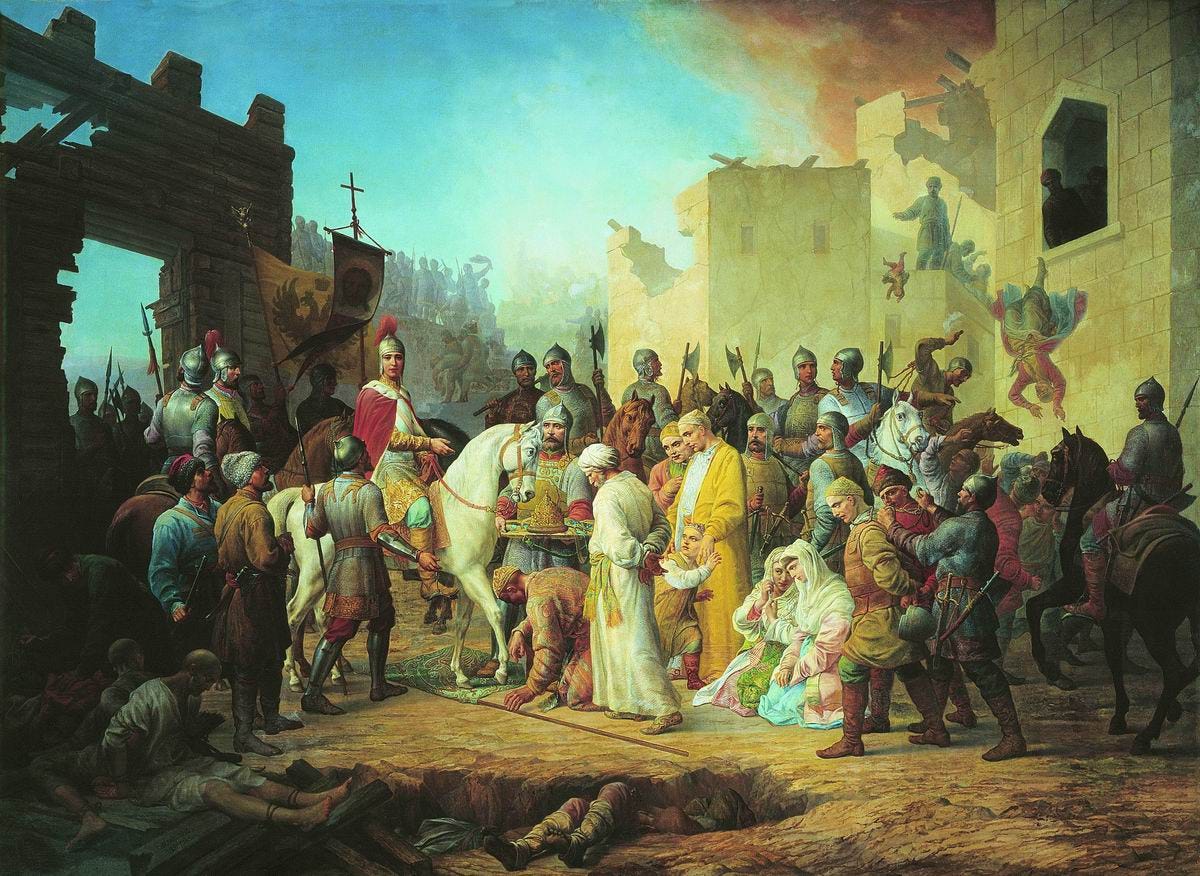

For the task of conquering Siberia the Stroganovs turned to Yermak Timofeyevich, a former pirate who once prowled the Volga. With financing and arms, Yermak set off in 1581-1582 leading a force of Cossacks and other adventurers over the Urals. Going up the Chusovoy River, they portaged into the basin of the Tobol, a tributary of the Irtysh, and soon came into conflict with the Khanate of Sibir.

The Khanate of Sibir was founded by Nogays from the steppe in the early 16th century, with the capital Qashliq established on top of an older Ugrian site near the confluence of the Tobol and Irtysh rivers. The existence of this Khanate and the immense wealth of furs that existed within its territories were not unknown to Moscow. In 1555 a political fraction within the Khanate sent an embassy to Moscow offering to become a vassal and to pay 1000 sable furs a year as tribute in exchange for political-military support. By the time of Yermak’s expedition Sibir had come under the control of Kuchum Khan, an adventurer from the steppe who reigned tyrannically over the khanate’s subject populations by demanding excessive taxes which were used to finance his wars against the Kazakhs. Additionally, Kuchum’s regime was aggressive in imposing Islam on the native Siberian peoples which only served to alienate them from Qashliq. With the arrival of Yermak’s Cossacks, they quickly revolted against Kuchum and sided with the Russians against the Khanate.9 By 1582 Yermak had captured Qashliq, sacking the town and sending back to Moscow the captured loot of "precious foxes, black sables, and beavers.”10 Kuchum managed to flee and continued a rearguard struggle against Russian, but this proved futile and in 1598 he was defeated for the last time at the mouth of the Irmen River, located south of modern day Novosibirsk. After this, he fled back into the steppes.11 The children and nephews of Kuchum Khan, the so called Kuchumovichi, continued to harass the Russians across western and southern Siberia for the next several decades and aided anti-Russian uprisings whenever they broke out in an admirable but ultimately futile attempt to reclaim their birthright.

The town of Tobolsk was soon founded near the former site of Qashliq in 1590 and the Russians quickly filled the void created by the khanate’s destruction. More precisely, they began demanding fur tribute from the local Siberian peoples. In fact, the local Siberians who had revolted against the onerous demands of Kuchum had largely just traded one yoke for another. Following behind the Cossacks and service people were the enterprising “promshlenniki,” fur trappers very similar to the French courier des bois of the New World. In general, Russia’s push into Siberia was very similar to the English and French expansion into North America. Driven by a sense of adventure and the allure of great profits, the Russians had discovered a New World of their own and marched to the shores of the Pacific in the pursuit of sable, beavers, foxes and other fur bearing creatures. The English diplomat Giles Fletcher who visited Russia in 1588 could already see how the Siberian fur trade was enriching Moscow: "furres… transported out of the Countrey some yeers by the merchants of Turkie, Persia, Bougharia, Georgia, Armenia, and some of Christiandom, to the value of foure of five thousand rubbles."12 By 1605, the revenue the the Russian state collected from Siberian furs had tripled, from 15,000 rubles to 45,000, and by the 1680's it had reached 125,000 rubles annually.13

After consolidating their hold over the region around Tobolsk the Russians pushed further east, sailing along Siberia’s river and portaging from one drainage basin to other just as how the Varangians had expanded into Eastern Slavic lands centuries prior. In 1604, they founded the town of Tomsk on the Tom River, a tributary of the Ob. Further up the Tom, Kuznetsk was founded in 1618. From the Ob the Russian portaged over to the Yenisei River, and founded the towns of Yeniseisk in 1619, Irkutsk in 1632, and by the mid-17th century Russia had reached the Pacific Ocean and the northern frontiers of China’s Qing Dynasty.14 With these earliest of settlements, Russia had planted the seeds which would later blossom into its empire in northern Asia, and the fruit it would bare would be in the form of the vast wealth of furs, minerals and energy which would proof crucial in Russia’s periodic waves of modernization and in its military struggles against Sweden, France, Germany and America. More than than, these seedlings of settlements would also later serve as Russia’s launch pads for further expansion into Central Asia and the Far East during the 19th century.

These early settlements built by Russia were “ostrogs”, small fortified towns that were mostly made of wood and which could house a few hundred people. They were defended by palisades, ditches, ramparts and guard towers. These strong points were used by the Russians as bases from where detachments would be regularly sent out to collect tribute in the form of furs from the local population. This tribute was known as “yasak” and tribute paying peoples were “yasachny.” Yasak was only imposed upon “aliens”, which for the Russians was more of a religious category than racial. For example, some Old Believer communities were classified as yasak despite being entirely Russian by blood.15 Conversion to Orthodoxy nullified the requirement for Siberians to pay yasak, and thus proselytization was largely discouraged as the Russians more interested in profits than saving souls.16

The Russians would often demand an oath of loyalty to the Tsar known as “shert” from its yasak paying vassals. Once given, the Russians would use this to claim eternal sovereignty over the tribe and would serve as sufficient justification for any punitive measures taken in order to bring them back “under the high land of the Russian Sovereign.”17

Shert and the paying of yasak were preconditions for trade with Russia, which was a greatly attractive to native Siberian peoples as Russia offered them goods they valued and often could not get from any other trading partner. While yasak is commonly equated as a form of tribute, some ambiguity existed in regards to the nature of the relationship between the Russians and native Siberians. While viewed by the Russians as tribute, payments were nevertheless often rewarded with material gifts, which Russians gave in order to encourage compliance.18 Thus, Siberians often viewed the payment of yasak less as tribute and more as trade. These gifts that they received for paying yasak included tobacco, alcohol, bread, sugar, wool, cloth, and various tools such as knives, axes, and copper pots.19 The goods which Russians gave were not equal in value to the furs they were receiving as yasak, and in 1766 the rate of exchange was standardized, where the gift would be 2% the value if the furs.20

As will be seen, Russia was not the only power in search of furs in Siberia. Whereas many tribes preferred to play multiple sides and only align with Russia and pay yasak when it was convenient, the Russians aimed to establish uncontested hegemony over the tribes that it viewed as its vassals. After all, defections among yasak paying tribes would mean fewer furs being sent back to Moscow, which would then reflect badly for the local voevoda, the military-governor of the ostrog and the man principally responsible for the collection of yasak from the surrounding tribes.

In order to enforce the payment of yasak, the Russians often took hostages from among the tribes it considered its vassals. These hostages were known as “amanat,” and were often captured in battle and lured away from the communities. Some voluntarily surrendered themselves. Those taken as amanat were typically "elites" within the community, such as a tribal leaders, elders, and shamans. The children of leaders were particularly favoured as amanat hostages. These hostages were kept under guard in ostrogs and would be presented and shown to their kin when yasak was delivered. Kinship ties and the importance the hostage had within the community usually ensured compliance.21

Russian imperialism in Siberia largely mirrored Turkic and Mongolian methods of empire. As mentioned already, as far as local Siberians were concerned, Russia largely replaced Kuchum as a tax collector primarily interested in the region’s furs. The Turkic analogue to yasak was “kyshtym,” which denoted the same thing.22 Just like the Russians, the Turkic nomads greatly valued fur as a commodity that could be sold to more distant sedentary societies. It really should be emphasized the extent to which Moscow learned the practices of empire from the Turko-Mongols who once ruled it. The yasak itself was Mongolian, from the word “a law.” During Russia’s own period of the “Tatar Yoke,” it paid yasak itself to the Golden Horde. The word amanat was Turkic, originally from an Arabic word meaning the same thing. In general, the practice if taking hostages to ensure political loyalty and compliance can be found across history, from the contemporary Tokugawa Bakufu of Japan to the ancient Romans.

Nevertheless, resistance against Russian depredation was common. The collection of yasak often required force and violence. As will be seen in the case of the Teles, the collection of yasak oftentimes better resembled raiding, piracy and extortion than anything else. In the lower Ob River, reindeer herders regularly raided Russian sleds and portages that carried supplies, while outposts on Sea of Okhotsk remained under a state of semi-permanent siege for years at a time.23 The aforementioned Kuznetsk ostrog on the River Tom was regularly threatened not only by local Siberians, but also by Zungar Mongols on the steppe who rivaled Russia as a hegemon over southern Siberia and intervened to assist their allies, a tribal grouping known to the as the Teleuts in their resistance to Russia. In the region around Kuznetsk efforts to collect yasak were almost immediately met by local resistance. In 1615 an assortment of tribes from across southern Siberia attempted to besiege the Russian settlement of what in the future would be Kuznetsk.

Known to the Russians as the White Kalmyks, of all of the native Siberian peoples Russia encountered, the Teleuts proved to be the most formidable and difficult to subdue. Of all the Siberian peoples, only the Teleuts had a state which could mobilize manpower and resources, as well as conduct diplomacy with neighboring powers. Soon after encountering each other, a century long conflict broke out between them. Unable to force the Teleuts into submission, the Russians instead launched several expeditions to Lake Teletskoye and elsewhere as a means to outflank the Teleuts and to break up their state by detaching them from their kryshtym tribes.

Rivalry with the Teleut Ulus and the Zungar Mongols

The Teleuts were a Turkic speaking, semi-nomadic people whose land, or ulus, encompassed the upper Ob River and the majority of the lowlands north of the Altai Mountains.24 At the time of their first contact with Russia, the Teleut Ulus spanned from modern Novosibirsk and Tomsk in the north to the northern Altai lowlands in the south, and covered the distance between the Irtysh River in the west and the River Tom in the east. As mentioned above, the Teleuts were remarkable in that they had a state which proved capable of rivaling the Russian one in southern Siberia. Often described in Russian sources as a “centralized feudal state,” the Teleuts had an army, tax collection, courts, as well as a nobility and a state assembly known as a the kurultai. According to the Gerhard Friedrich Miller, an 18th century German historian who similar to Johann Fischer pioneered the study of Siberia, in the 17th century the Teleuts could call upon a force of 1000 warriors out of a total population of about 5000.25 While seemingly too close a ratio of soldiers to civilians, it should be noted that nomadic societies were often capable of mobilizing a far higher percentage of their population for war than sedentary societies are able to, largely because skills developed in the course of animal herding were dually applicable in warfare.

Alongside a state apparatus, the Teleuts also held sway over a small empire of tribute paying kryshtym tribes. These included various Tatar tribes such as the Chats who lived to the north along the Irtysh and Tom Rivers, the Barbara Tatars who lived to the west on the Barbara steppe, various Shor Tatars, as well as some Yenisei Kyrgyz tribes to the east beyond the Salair Ridge in the Minusinsk Basin. Teleut power also reached deep into the Altai Mountains, and many of the highland tribes were tributary paying vassals of the Teleuts, including the Teles at Teletskoye.

Diplomatic contact between Russia and the Teleuts began in March 1609. An agreement was made between the two which called for the provision of military-political assistance to each other if requested.26 At time of Russia’s first contact with the Teleuts, they were under the leadership of Prince Abak, the nephew of Kuchum Khan, and someone the Russians described as “cunning.”27 As a part of the 1609 agreement Abak swore an oath to the Tsar, but was not compelled to pay yasak. The agreement was essentially an alliance, the only such agreement Russian made with any Siberian people. It also gave Abak the right to nomadize as far north as Tomsk. The agreement was of great importance for Russia as it provided them with breathing space. The establishment of friendly relations with the Teleuts neutralized one of the main potential threats that existed to the survival of Tomsk, which at the time was founded five year prior and remained vulnerable.28 It should be noted that Russia’s foothold in Siberia at this time was particularly tenuous, not merely because of how young it was, but also because of the civil and military unrest raging across the Russian heartland at time, a period known as the Time of Troubles which followed the deaths of Ivan IV and Boris Godunov. Suffering from mass famine and Polish invasion, Siberia was very much of secondary concern at this time.

Despite an initially friendly start to relations, they quickly soured. Soon after 1609 the Teleuts came under attack by the Zungars Mongols who nomadized west and south of the Altai Mountains, beyond the Irtysh River. With Russian assistance not forthcoming, Abak lost the main incentive he had for maintaining cordial relations.29 Relations soon deteriorated following aggressive Russian efforts to collect yasak, including from tribes that paid kryshtym to Abak and which he viewed as his own. Teleut efforts were largely directed against Kuznetsk and the Siberian tribes that Kuznetsk attempted to collect yasak from. Yet, as Teleut-Zungar relations worsened and the Zungars increased their raids on the Teleuts, Abak realigned with Russia in 1621. Russian-Teleut relations then worsened again, and in 1629 Abak succeeded to forcing many Tatar tribes across Siberia to stop paying yasak to Russia, an affair which will be discussed in greater detail below.30

The remainder of the 17th century Russian-Teleut relations followed this initial pattern. Periods of rapprochement were soon followed by periods of hostility.31 There were several issues that drove this conflict, including Russian territorial ambitions, rivalries over fishing grounds, mutual cattle raiding, Teleut refusing to return run away Russians, but the principle issue was the conflict over the smaller tribes of the region, over whom the Russians and Teleuts both attempted to extract tribute from. Some Siberian tribes, caught in between the larger two powers and unable to resist either, were forced to pay tribute to both the Russians and Teleuts. Other tribes tilted back and forth between the two, paying tribute to whom was stronger and more demanding at the given moment. Even when the Teleuts could not force other tribes into submission they supported all resistance against Russian demands for yasak, particularly among the Chat, Barbara and Shor Tatars.32 The Teleut Ulus functioned as a rival center of gravity in southern Siberia, drawing many of the small tribes away from Russia’s orbit and into theirs.33 Tribes dissatisfied with Russian demand would even migrate towards the Teleuts or in some cases the Yenisei Kyrgyz in the Minusinsk Basin. In short, the Teleuts rivaled Russia as hegemon of southern Siberia. Prior to the coming of the Russians to Siberia, a very similar dynamic existed between the Teleuts under Abak’s father Prince Khonai and the Khanate of Sibir, where the two rivaled each other for control over the tribes of Ob Basin.

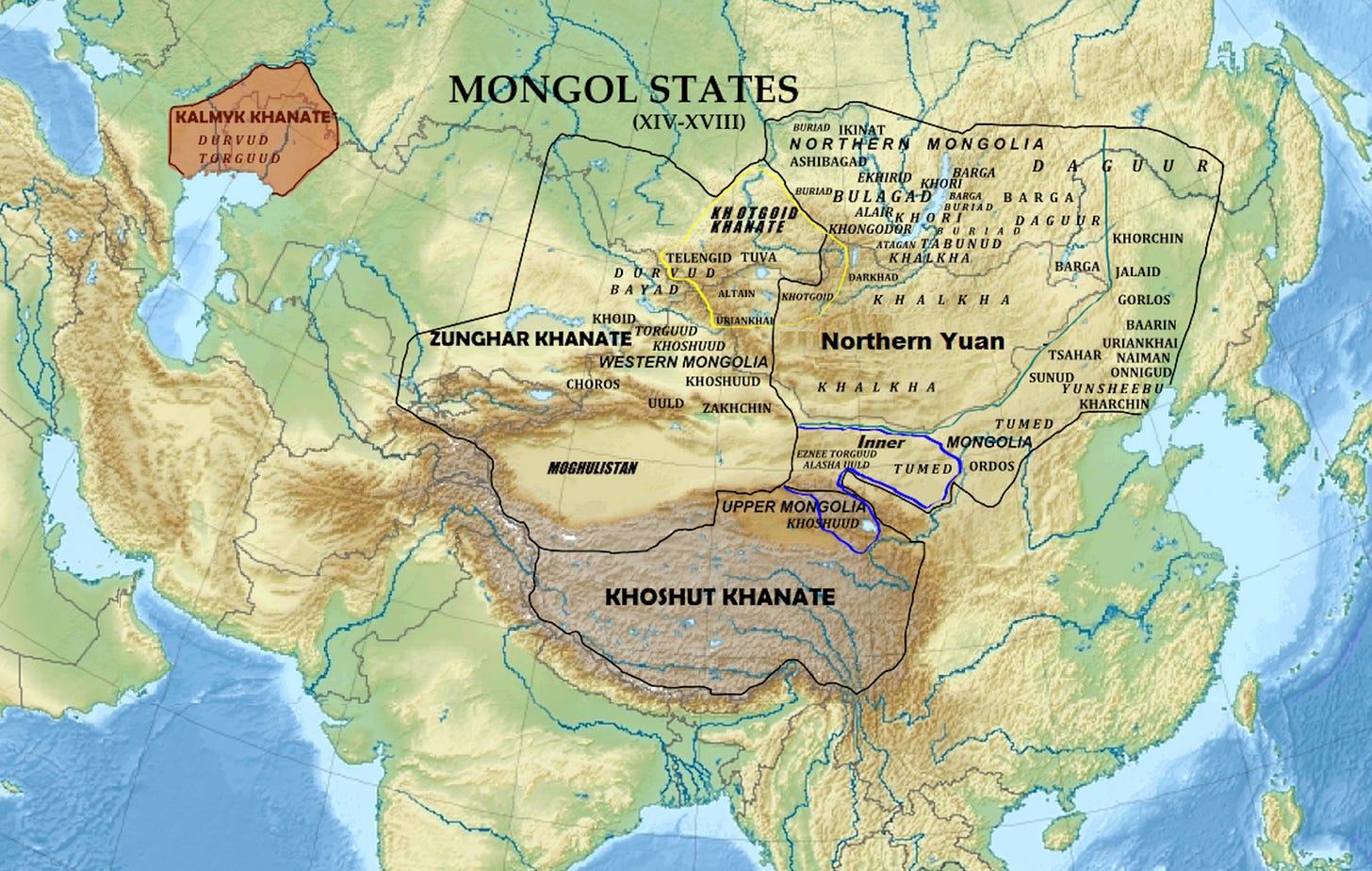

Russia’s Teleut problem was only complicated by the existence of the powerful Zungar Khanate south, beyond the Irtysh River. The Zungars were a tribal union made up of Oirat (meaning “Western”) Mongols headed by the Choros clan, who nomadized in the lands of today’s northern Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan. Even more than the Teleuts, the Zungars proved to be the single biggest obstacle to further southward expansion into Inner Asia by Russia during this time. Similar as with the Teleuts, the Russian-Zungar conflict centered over resources, namely salt lakes on the steppe, and tributary status of several tribes across southern Siberia.

The first flare up between the Russians and Zungars occurred in 1611, when a Russian detachment forcefully expelled the Zungars from a salt source on outskirts of Tara, a Russian settlement on the Irtysh River upstream from Tobolsk. Later in 1620 the Russians attempted to build an ostrogs near the Yamyshev salt lakes, located south of modern day Pavlodar. The Russians were forced to withdrawal due to Zungar pressure, but continued to stealthy return to extract salt under constant threat of attack. Eventually in 1635 an agreement was made were the Russians were allowed to come to the lake and trade with the Zungars for the salt. A major trade fair grew up here, and was the largest Russian trading post on the eastern steppes prior to the creation of the Russian-Qing fair at Kyakhtia after 1727.34 In 1636 the Hong-Taiji (from the Chinese word Húntáijí 浑台吉, which means “Crown prince”) Erdeni Batur built his capital near Yamyshev Lake, a fortified town which was later abandoned following his death 1653.

The Russians and Zungars were also conflicted over the tributary status of several south Siberian tribes, included the Yenisei Kyrgyz, as well at the Teles at Lake Teletskoye. Eventually the two sides agreed that the Kyrgyz would pay tribute to both, but disputes regarding this issue in general persisted throughout the entirely of the Russian-Zungar relations.35

A dynamic emerged within the three-way relationship between Russia, the Teleuts and Zungars. Whenever hostiles broke out with either the Russians or the Zungars, the Teleuts would respond by aligning with the other power to in order balance against whomever was more threatening at any given moment. This would meant that when the conflict escalated between the Russians and Teleuts, the latter would often go the Zungars to pay tribute and seek help. The Zungars would then intervene on behalf of the Teleuts and take joint actions against Russia in the form of raids and sieges of ostrogs.36

Simultaneously relations remained relatively tense with the Zungars throughout the 17th century. The Zungars regularly signaled openness to becoming Russian vassals as they hoped to draw Moscow into their conflict with the Altyn Khans, rulers of the Khalkhas in eastern Mongolia, but in practically terms they remained a constant threat to Russia’s Siberian possessions. As will be seen, the presence of powerful Zungar Khanate beyond the Irytsh River made any Russian southward advances into the steppe zone impossible throughout the 17th century, and this problem would only be resolved thanks to geopolitical developments occurring elsewhere.

The 1631 Anti-Russian Coalition under Mirza Tarlav and the Russian Expedition to Chingis

The Teleut’s anti-Russian agitation culminated in 1628 when a widespread rebellion against yasak payments broke out among Siberian Tatar tribes, particular the Chats near Tobolsk, Tara, Tomsk, as well as those on the Barbara steppe.37 This rebellion soon came under the leadership of Mirza Tarlev, a Chat nobleman from near Tobolsk who had previously been associated with Kuchum Khan and was at the time the son-in-law of Abak. Tarlev led his followers south up the Ob River, where they founded the fortified town of Chingis in 1630, which was located on island in the river. Outside of Russia’s immediate reach, these Tatars under Tarlev began harassing the Tomsk uezd with raids and attacking yasak paying tribes in attempt to force them to break off their ties to Russia.38

Tomsk Voevoda Petr Pronsky feared that this anti-Russian coalition under Tarlev would attract additional followers and would snowball into becoming an unmanageable crisis. Not only would Russian’s collection of furs decrease enormously, settlements such as Tomsk, Kuznetsk and others could becoming seriously threatened if the rebellion expanded and received support from the Teleuts and Zungars. Thus, in early March 1631, a detachment of several hundred Cossacks and loyal Tatars headed by Yakov Tukhachevsky was sent out to defeat Tarlev and capture Chingis before the situation deteriorated further. The Russians did not want Abak’s Teleuts to join forces with Tarlev at Chingis so they made haste, traveling by skiis and dog pulled sleds, and they managed to reach Chingis in 2 and half weeks, half the usual time for such a journey.39 Initially the Russians were content to simply besiege Chingis and eventually force Tarlev to surrender, but when news came that Abak was advancing on their rear with reinforcements Tukhachevsky decided to immediately storm the fortress.

With the small canon they had brought, the Russians stormed the fortified town across the frozen river while others held back some of the reinforcements which were beginning to arrive. The storm of Chingis was a success. Tarlev fled with his close followers into the Karakansksy forest north of town, but was soon tracked down during the pursuit and killed. By this time the Teleuts had arrived with some Zungars at their aid. The Russians under Tukhachevsky fortified themselves in Chingis and now came under siege themselves. After some time the Russian detachment sallied out and fought the besiegers off, and then returned to Tomsk.40

The expedition by the Tomsk Cossacks to smash the anti-Russian coalition under Tarlev was a major success. With Tarlev’s death the coalition fell apart, the Chats returned back to lands and resumed payment of yasak, while the Barbara Tatars went back to the Barbara steppe.41 Remnants of Kuchum’s followers likely fled to the Irtysh and largely ceased to be a problem for Russian henceforth. The revolt was successfully contained and prevented from spiralling any further and yasak payments continued from the former rebels. In general, from the Russian standpoint the situation had stabilized.42 Yet relations with the Teleuts continued to remain tense. While stripped of some allies, Abak himself was undefeated. Moreover, the several of Tarlev’s children had fled to the Teleuts, and despite Russian demands that they be given up, Abak continued to provide them with shelter.

Pushchin’s 1632 Expedition Up the Ob River to the Katun-Biya Rivers

With the change in the local balance of power following the destruction of Tarlav’s anti-Russian coalition the new Tomsk voevoda Ivan Fedorovich Tatev decided to send an expedition up the Ob River to the confluence of the Biya and Katun Rivers where an ostrog would be build.43 At the time much of the upper Ob remained terra incognita for the Russians, but enough was known to lead the Russians to believe the Biya-Katun confluence would be an ideal spot for a new ostrog.

The valley of the Biya in particular was reported to have rich pine forests which would make construction easy.44 Moreover, the Biya and Katun Rivers were known to have ample sources of food available in terms of fishing and game, but most importantly, the land there was ripe for agriculture. This was of critical importance to the Russians has their settlements across Siberia faced constant food shortages. Due to the local climate and land agriculture was difficult, and grain had to be imported from European Russia beyond the Urals. This of course was extremely expensive and incredibly inefficient, with a supply chain that would often take 5-6 month for grain to be delivered, in addition to requiring manpower which could be better used elsewhere. The colonization of the northern Altai lowlands had the possibility to at least partially resolve this problem. Grain harvested in the relatively warmer and more fertile valleys of the Katun and Biya could be sent down river to Tomsk, Tara, Tobolsk, Tyumen and elsewhere, reducing their dependency on imported grain.45 Siberia’s lack of grain production plagued Russia well into the 19th century, and just as how it prompted expansion into the northern Altai lowlands, it also motivated the annexation of what would later become the Russian Far East from China’s Qing Dynasty in the 1860’s.46

There were strategic considerations as well. The Russians knew from Central Asian merchants that traveled north to Siberia and traded in Russian settlements that there was an island at the confluence of the Biya and Katun Rivers which served as a major crossing point over the Ob. This was the main crossing used by the Zungars to raid Kuznetsk and Tomsk, which by the 1630 had already occurred on several occasions. Russians soon familiarized themselves with this crossing as diplomats often used it on their way to the Zungars. The route to the Zungars was known as the “Kalmyk Road,” which led from Kuznetsk, up the Kondoma River, over the Salair Ridge, down the Bekhtemir River to the Biya-Katun confluence.47 Reportedly the distance between the crossing over the Biya-Katun confluence to Kuznetsk was only 5 days on horseback and 7 days on skiis.48 Thus, establishing an ostrogs would not only have secured a strategic river crossing frequented by merchants, it would guard the southern approaches Kuznetsk and Tomsk.49 And with the Zungars less able to intervene north of the Biya, Russia would have a much firmer hold over the tribes there, and better able to extract yasak payments from them. It also partially encircle the Teleuts, and hopefully weaken their hold over their own tribute paying kryshtym tribes, including the Teles at Lake Teletskoye. Lastly, an ostrog at the Biya-Katun confluence would serve as a base for further expansion, primarily into the Altai Mountains and south to the Irtysh. In the words of Fischer, the proposed ostrogs “would lead to further discoveries.”50

Lastly, an ostrogs at this site would better enable the collection of yasak from the local Kergasal tribe who lived near the Biya-Katun confluence.51 Kuznetsk in the past had tried to collect yasak from this tribe but had struggled to do so regularly, largely due to the pressure that the Teleuts exerted on them. The hope was that with a permanent Russian presence in the immediate region, the Kergasals would be firmly under Russian influence and control.

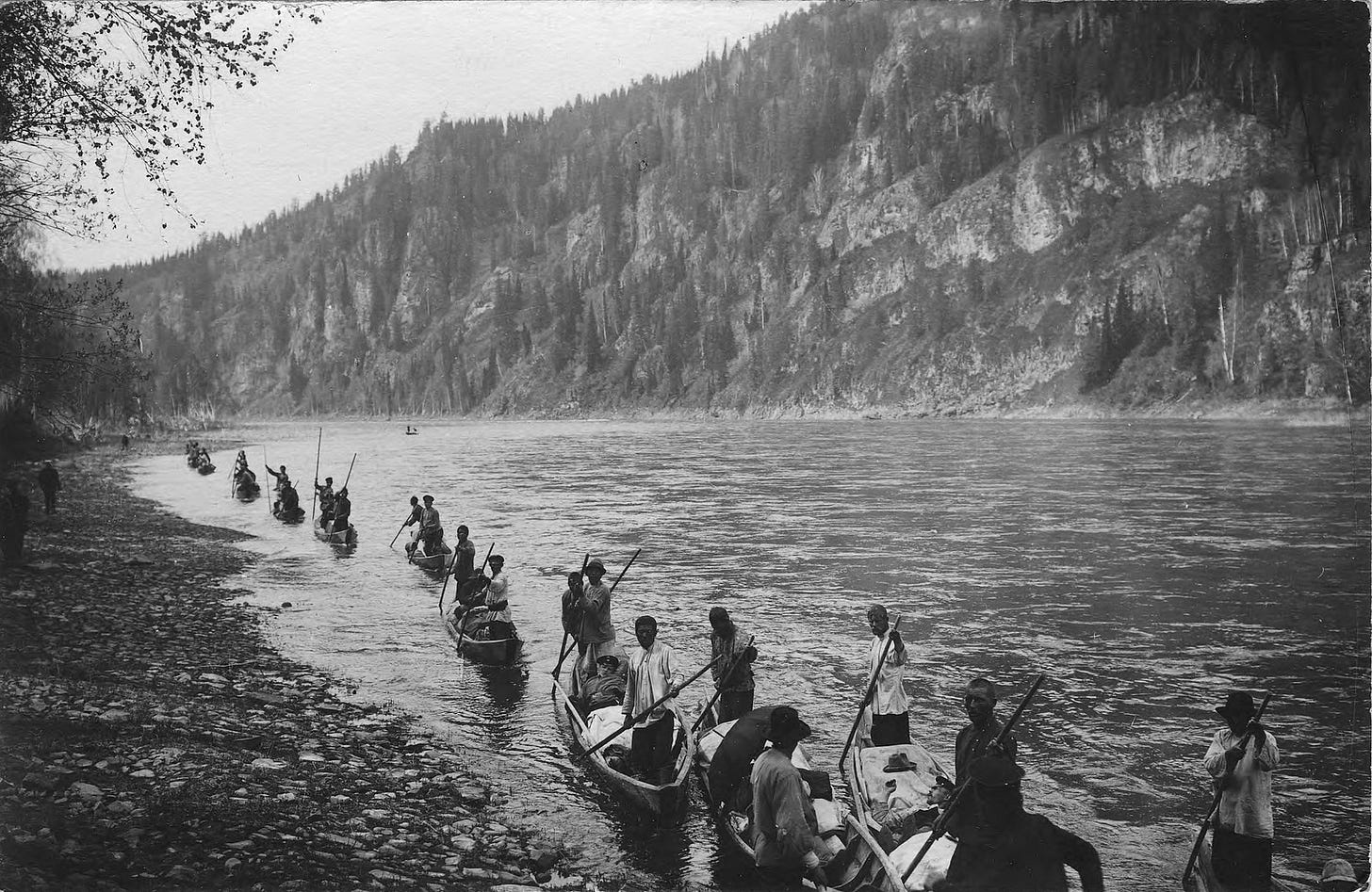

Thus was the context behind the expedition by Tomsk Cossacks headed the Boyar Son F. Pushchin in 1632 to build an ostrogs at the confluence of the Biya-Katun Rivers. The detachment left Tomsk eon 20th July 1632, travelling from the Tom to the Ob, and then up river to its source. Along with Pushchin himself, the force consisted of 60 Cossacks and 2 translators, making the detachment number 63 people in total. Travelling 16 to 18 verstas a day in three doshchaniks, small riverine boats, Pushchin’s detachment reached the mouth of the River Chulmysh by the 31st of August.52 Three days after passing the Chulmysh, on 3rd September, the detachment was ambushed by a Teleut force under Abak that stopped the Russians in their tracks and forced them to withdrawal back down the Ob to Tomsk.53

According to Alexei Pavlovich Umansky, the preeminent Soviet historian of Teleut-Russian relations, there two different accounts of how the ambush played. The first is based on the “interrogation speech” by Pushchin, which he gave upon returning to Tomsk where he debriefed the authorities on what happened. The story according Pushchin as retold by Fischer, the Russians were ambushed somewhere around the Chumysh River by Abak’s Teleuts who were being assisted by the Kuchumovich Prince Devlet Kirei in addition to a force of Zungars. At this point Pushchin’s detachment was forced into a defensive posture and came under siege in a bloody battle that lasted five days. Eventually the Russian managed to escape and retreated back to Tomsk.54 Umansky believed Pushchin exaggerated the strength of the Teleuts as well as the extent of his loses and the intensity of the battle in other to avoid responsibility for the expedition’s failure.55

The second version is based on the “interrogation speech” by Aidar from 18th September 1632, which Umansky believes to be the much more trustworthy source. It is unclear who this Aidar was. Presumably, he could have been Aidar, son of Prince Mandral of the Teles at Lake Teletskoye, but this Aidar was likely not in Russian custody until 1633, following Sabansky’s first expedition to the lake, which will be discussed further below. Regardless of his identity, Aidar’s narrative of the expedition mirror’s Pushchin’s up until the ambush on 3rd of September. The ambush began with Teleut bowman on the left bank of Ob firing a volley of arrows against the Russian doschaniks. The Russians then returned fire with a musket, which sent ambushers fleeing. 30 streltsy from the third doshchanik then made landfall on the left bank and found the place deserted. They continued their search inland, and at the edge of a large pine forest they encountered 20 riders and entered into negotiations at a distance. These Teleuts spoke in Mongolian in order to trick the Russians into thinking they were Zungars, and thus more numerous and more threatening than they truly were. The negotiations ended uneventfully, with the Teleuts saying had attacked the Russians to protest the collection of yasak.56 According to Umansky, the expedition then halted for some time to discuss the situation. Fearing that they would encounter stronger resistance that they would not be able survive, the Cossacks in the end they decided to return back to Tomsk. The return journey less than two weeks, and upon returning Pushchin gave, as Umansky believes, his highly exaggerated version of the story.57 According to Umansky, the ambush and subsequent negotiations likely occurred just before the modern day city of Barnaul, near the village of Kislukha.58

If nothing else, the Pushchin expedition functioned as a reconnaissance mission that scouted the upper Ob. And despite its failure, Russia did not abandon it plans to eventually construct an ostrog at the confluence of the Biya and Katun Rivers. Proposals were put forth for this repeatedly throughout the 17th century and considered in 1651, 1667, 1673, and 1683, but the Russians remained hesitant.59 Only in 1684 did Russia reactivate its advance up the Ob, with the construction of the Urtamsky ostrog, located about 150 kilometers downstream from modern day Novosibirsk but still very distant from the Biya and Katun Rivers.

In the meantime, the failed expedition halted any further Russian expansion up the Ob and only served to antagonize Russian-Teleut relations further. Despite being isolated following the defeat of the anti-Russian coalition in 1632, the Teleuts remained militantly opposed to any further Russian penetration into their territory. This prompted the Russians to change course. It was understood that further expansion in the Ob basin needed to advance along its flanks as opposed to direct movements.60 With expansion up the Irtysh also impossible for the time being, the Russians decided to gain a foothold in the high Altai Mountains themselves. The target for this was Lake Teletskoye, which was known for its wealth of game and fish, and whose location deep in the mountains would be secure from Teleut or Zungar attack. Thus, in the following winter of 1632/1633, the Boyar Son Petr Sabansky was dispatched to the Golden Lake to punish the Teles for attacking yasak paying tribes and to bring them back “under the high land of the Russian Sovereign.”61

Sabansky’s Expedition in 1633 to Lake Teletskoye

In the years following the founding of Kuznetsk in 1618 expeditions were sent out in all directions with the purpose of making contact with any tribes that could be found and subjecting them to Russian power. Teams were sent out to explore the valleys of the upper Tom, the Kondoma, Mrassu, and parts of the Biya. Officials in Kuznetsk noted that Tatars in the Kondoma valley were particularly resistant to paying yasak. This was in large part a consequence of bordering the Teleut Ulus to their west, as the Teleuts would have applied pressure on them to not associate with the Russians.62 It was during this initial exploratory phase that the Russians first reached Lake Teletskoye. In 1624/1625 Kuznetsk Voevoda Evdokim Ivanovich Baskakov sent a detachment headed by Sidor Federov and Ivan Putimets numbering 220 people to Lake Teletskoye to collect yasak from the Teles.63 From Kuznetsk they traveled up the Kondoma River to the Antrop River. From there they crossed over to the Lebed River which flows the Biya River at modern day Turochak. They then followed the Biya up to the lake itself.64 Future expeditions to the lake presumably followed a similar route.

Following this expedition the Teles only paid yasak irregularly, but after 1630 they stopped paying it altogether, which was likely a consequence of Tarlev’s anti-Russian coalition which temporary broke Russia’s hold over many.65 With the desire to once again make the Teles pay yasak and to expand deeper into the Altai Mountains, the Tomsk voevoda dispatched a new expedition to Lake Teletskoye which sent out in either December 1632 or February 1633. To quote Fischer, “in 163366 the Tomsk Cossacks had attempted to lay an ostrog at this place, where the river Biya and Katun unite, but this was prevented by the Teleuts. However, they were not deterred from making expedition in the same year67 to the same place and to reach the peak of the river Biya, led by the Boyar’s Son Petr Sabansky.”

The expedition began in Tomsk and traveled first to Kuznetsk, where Sabansky further strengthened his force. After spending 10 days in Kuznetsk, the detachment traveled on skiis. Upon climbing the valley of the Biya and reaching the lake, the leader of the Teles, Prince Mandrak, saw that the Russians were stronger than him and quickly fled to the southern shores of the lake on boats. Either due to confusion or negligence, while fleeing from the Russians Mandrak left behind his wife and son Aidar on the northern shore of the lake, who were then quickly captured by the Cossacks. Having taken amanat hostages which would compel the Teles to pay yasak, the Cossacks returned back to Tomsk by May 6th.68

In the following year, in 1634, Mandrak arrived to Tomsk to ransom his family. He swore an oath of loyalty to the Tsar and agreed to pay 10 sable furs per Teles each year in order to secure his family’s release. According to Fischer, the Russians accepted Mandrak’s oath at face value and released the hostages, and having gotten what he wanted, Mandrak once again ceased to pay yasak.69 Other sources, including documents from the “Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts” (РГАДА), state that Mandrak took Aidar’s place as an amanat hostage and remained in Tomsk. Following this, Aidar continued to pay yasak to the Russians. These same sources state that in 1637/1638, a Russian named Maksim Astafev travelled to the Teles to collect yasak, but Aidar refused to pay until Mandrak was released.70 This second version of events is particularly confusing because, as will be seen below, Mandrak appears to have been with Aidar at Lake Teletskoye in 1642 during Sabansky’s second expedition to the lake. If this second version is believed to be true, Mandrak was presumably released from captivity in 1638 as an act of good faith in order to meet Aidar’s demands. To go one step further, it is possible that Fischer was working with incomplete documentary records and produced a simplified retelling of the full story.

Either way, Sabansky’s expedition in 1633 proved largely futile and unfruitful. For reasons that are not clear, the Russian released Aidar and/or Mandrak upon their word of honour that they would resume payments of yasak, which subsequently did not happen. Nevertheless, the expedition served at least as a reconnaissance in force: the route to Teletskoye was clearly determined and so was the strength of the Teles. While the journey to the lake was arduous and through territory that they only loosely controlled, the Russians could at least be confident in their ability to defeat the Teles with force of arms.

Sabansky’s Second Expedition in 1642

Following the expeditions by Pushchin and Sabansky, Russian relations with the Teleuts continued to ebb and flow. Mutual raiding and rivalry over the status of smaller tribes continued parallel to regular trade between the two. In general, the Russians and Teleuts were complimentary trading partners, as both had goods the other desperately needed. As mentioned above, the Russians faced a general scarcity of food, whereas the Teleuts, being nomadic and largely isolated from sedentary cultures, lacked the crafts and tools that only a sedentary society could produce. Thus, ample trade was carried out where the Russians exchanged cloth, tools, dishware and weapons in exchange for cattle with the Teleuts. Trade fairs and markets were occasionally closed due to worsening relations and increased raids, but they always reopen once the situation had calmed.

Not only were the Russians partially dependent on the Teleuts to alleviate their food shortages, they also depended on the Teleuts to act as a strategic buffer between themselves and the Zungars, as well as the Yenisei Kyrgyz to the east who Russia also had hostilities with.71 Despite some cooperation between the two against Russia, the Teleuts generally also had an antagonistic relationship with the Zungars. Thus, from the Russian point of view the Teleuts would absorb the majority of the Zungar’s raids into Siberia. Again, it must be emphasized just how vulnerable Russia’s settlements in Siberia were. They faced the very really possibility of being attacked and driven out from the region, as exactly was done by the Qing Dynasty who drove the Russians out of the Amur valley in the 1690’s.

In 1635 Prince Abak, who long served as ruler of the Teleuts, died.72 With his death came significant internal upheavals within the Teleut Ulus. Immediately after his Abak’s death several tribal leaders were hesitant to align themselves with his son Koka, and instead pledged themselves to his nephew Machik, and thus splitting the ulus. Koka inherited the majority of the Teleuts, forming the Big Ulus, which was located to the west, while Machik’s Little Ulus was in the east, consisting of only 1000 people, of whom 200 were warriors. In addition to splitting the Teleuts themselves, Koka and Machik also divided the kryshtym paying tribes between themselves. In the case of the Teles, they paid kryshtym to Koka in 1642.73

Despite their small numbers, Machik’s Little Ulus caused considerable problems for Russia. Koka’s Big Ulus was by comparison much more amenable to Russian interests. For example, in 1636 Koka allied with the Russians against the Yenisei Kyrgyz.74 While there were likely several reasons for the division among the Teleuts, with personal and political loyalties likely being most important, the differing stances taken towards Russia by Koka and Machik were also likely major contributing factors. Later in 1688 following Machik’s death the Teleut Ulus was reunified under Koka’s son Tabun who leadership who continued to harass the Tomsk and Kuznetsk uezds and challenge Russia’s sovereignty over its yasak paying tribes.75

By the late 1630’s the Teles had once again broken away from Russia and stopped paying yasak. In January 1640 an order arrived from Moscow to Kuznetsk which demanded that another expedition be sent to Teletskoye to collect the past years’ unpaid yasak from the Teles. This order remained unfulfilled for some time. During the winter of 1639/1640 the efforts of the Kuznetsk Cossacks were concentrated mainly on collecting yasak from other tribes more nearby who were also behind on paying yasak, particularly those along the Kondoma and Mrassu Rivers. Russian pressure had the ultimate effect of causing many of those Tatars to flee to the Yenisei Kyrgyz beyond Russian reach.76

Unable to extract yasak from the Tatars in the lower valleys of the Altai, the Russians once again turned their attention to the Teles at Teletskoye and finally executed the order from 1640. This new expedition, once again headed by Boyar Son Petr Sabansky from Tomsk, had grander objectives than the previous one. This time not only would the Teles be subdued and forced to pay yasak, the Russians also planned to construct an ostrog on the shores of the lake in hopes that a larger Russian settlement would eventually take root there. With a foothold deep within the Altai Mountains, the Russians would be able to facilitate greater control over the local highland tribes, in addition to outflanking the Teleuts from the south.77

Likely following the same route as in 1633, Sabansky departed from Tomsk and passed through Kuznetsk before arriving to Lake Teletskoye sometime in early 1642. Upon reaching the lake the Russian found the northern shore was already abandoned, as the Teles had fled in advance to fort at the mouth of the Chulyshman on the southern end of the lake.78

The Russians had initially planned to ski across the lake if need be, but they were surprised to the find that the lake was not frozen over. So instead the Russians were forced to build ships on the northern shore and sail to the far end of the lake where the Teles were located. While Sabansky and most of the detachment sailed, a small force of 80 Cossacks led by Petr Dorofeesev were ordered to take the overland route.79 They likely traveled along the northern and eastern sides of the lake which today has hiking trails. Once regrouped on the southern shores the Russians quickly came under attack by a force of Teles led by Mandrak who sallied out from their fort. The Russians easily fought them off, and the Teles withdrew having suffered several injuries. At this point the confrontation settled into a siege.

Eventually Mandrak made an attempt to leave the fort with some of his people and flee to the Sayan Mountains, but he was captured by the Russians. His son Aidar remained in the fort with the rest of the Teles and waited for reinforcements to arrive. After 12 days’ time the allies of Aidar arrived from across the lake and attacked the Russians. Upon hearing the commotion outside the walls and realizing his allies had finally arrived and were attempting to break the siege, Aidar too launched on attack on the Russians. Despite being pressed from both sides the Russians ably fought off their attackers, and even managed to capture Aidar and a large number of the Teles. The reinforcements that had come from across the lake now attempted to flee in their ships but were chased by the Russians and during the pursuit a great number of them drowned. While still at the lake under Russian custody, Prince Mandrak swore an oath of loyalty to the Tsar and promised to go and collect yasak from his ulus, including from those living along the Chulyshman. According to Fischer, Mandrak return after 12 days with with 50 packs of sable furs.80

With the Teles subdued, Sabansky turned his attention to building an ostrog somewhere on the lake. Due to a lack of food, 60 Cossacks and 17 Tatars were sent back to Kuznetsk while the rest of the detachment remained at the lake to search for a suitable place for the ostrog. Reportedly the Russian scouted the length of the lake but found nowhere suitable for a settlement. Everywhere the cliffs descended too sharply down to the shoreline, with either a very narrow flat stripe of land between the mountains and the lake or known at all. There were a few capes located along the shore, most notable being Cape Artel, but these places were not big enough for what the Russians required. As spring arrived Sabansky and his men returned to Tomsk. Upon returning he recommended that instead of building an ostrog at Lake Teletskoye one should be built at the mouth of the Lebed River where it flows into the Biya, shortly downstream from modern day Turochak. For reason unspecified the voevoda rejected this proposal.81

The Cossacks headed back to Tomsk, taking with them Prince Mandrak and his entire family including Aidar at amanat. According to Fishcer, somewhere along the way Sabansky stopped to collect yasak from the Tatars along the “river kolsheya,” a river whose modern name cannot be determined, and while doing so Mandrak found is chance to escape and fled from the Russians. This proved to be Mandrak’s last taste of freedom. Out of love for his family, as Fishcer puts it, Mandrak appeared in Tomsk soon after. He traded places with his son Aidar as Russia’s hostage and the rest of his family were freed. Mandrak soon died three years in 1645, presumably still in Tomsk, and with his father’s death, the Teles once again stopped paying yasak.82

Later Expeditions

In spring 1642 the Teles appeared to be totally defeated and at the mercy of Russia. Their homeland had been invaded and conquered, and their leaders were captured and hauled off to Tomsk. As the Russians departed the Teles likely thought they would never again see Mandrak or Aidar, yet affairs themselves played out in favour of the Teles. The Russians opted only to take the elderly Mandrak as amanat and set the much younger Aidar free to collect yasak for them. This proved most beneficial for the Teles. Had Aidar been held as a amanat instead of his father, it is possible that following Mandrak’s imminent death there would have been a succession crises. But instead the Teles had Aidar, who remained young and ruled over them for another few decades. Additionally, Aidar held the Russians at bay much more successfully than his father had done, using both local geography to his advantage, as well leveraging the geopolitical situation in the Altai region in his favour. And when the time finally came when submission to Russia was no longer avoidable, the Teles secured for themselves more favourable terms than what had initially been offered. Their decades of resistance were not for nothing.

In December 1643, while Mandrak was still alive, the pyatdesyatnik83 Kuzma Volodimer was killed on his way to Lake Teletskoye to collect tribute from the Teles. After an investigation the Kuznetsk Voevoda Afansy Zubov concluded that the Teles were not behind the killing and it was the fault of yasak paying Tatars near Kuznetsk. Aidar received word of this affair, and anticipating the worst, he preemptively sent the Teles to the Sayan Mountains out of reach from any potential Russian retaliation. Nevertheless, in 1644, an order arrived to Kuznetsk for Aidar to be taken to Kuznetsk and “hanged, so that it will be seen that henceforth, others will not be disobedient to steal as such, and to beat to death the Russian Sovereign’s people and to rob service people.”84 It is unclear whether this was in response to the killing of Volodimer or ordered for some other reason.

Following Mandrak’s death in 1645 and Aidar’s abscondment from yasak payments, the Russians sent out another expedition to Lake Teletskoye. This expedition was led by Kuznetsk Voevoda himself, Afansy Zubov, as well as his son Boris Zubov.85 Reportedly several yasak collectors had already been dispatched to the lake but were unable to find the Teles. The expedition consisted of over 100 people and traveled in the summer of 1646. The trek up to the lake took five grueling weeks according Zubov, who describes the journey as such: “I went from the Kuznetsk ostrog with Your Sovereign’s service people to the Teletsky Tatars across the steppe and over mountains, and between high mountain gorges, and over large rivers, the most necessary route for more than five weeks and endured every need and hunger.”86

Similar to Sabansky in 1642, Zubov built ships on the shore of the lake and sailed them across to where the Teles were located. After three days of fighting the Russians defeated the Teles and forced them to pay yasak. Aidar and his family were captured again, and again they were taken by the Russians as amanat. Somewhere along the way, just like his father before him, Aidar managed to escape, but showed up later in Kuznetsk to pay yasak, where he also swore an oath to the Russian Tsar.87 A Prince Urguik who was presumably was Aidar’s son or possibly his bother was kept by Zubov amanat and remained in Kuznetsk.88 Regardless of this, Aidar soon broke away from Russians and ceased paying yasak. Following the 1646 expedition Aidar cultivated closer relations with the Zungars with whom the Teles could trade with instead of Russia.89 Later, Koka sent an envoy to Tomsk to demand an explanation for Zubov’s expedition against the Teles, who at the time paid kryshtym to Koka.

In 1648 an order came from the Tsar for Aidar to be captured once again. In the winter of 1650 Kuznetsk Voevoda G. K. Zasetsky sent a detachment led by the Boyar’s Son Roman Groshevsky to Lake Teletskoye with instructions to lure Aidar to Kuznetsk under pretenses of “important state affairs” that needed to be discussed. In March 1650 Groshevsky returned empty handed and reported that Aidar had refused to join him as it would soon be springtime when rivers would rise due to the melting snow and make his return trip impossible. He instead promised to come to Kuznetsk during the summer once the water level in the rivers had lowered again. He never showed up. Around this time Prince Urguik who was being held as amanat in Kuznetsk committed suicide.[101]

The last armed Russian expedition to Lake Teletskoye was possibly in March 1653, but there are reasons to doubt its veracity. Led by the Cossack Ataman Petr Dorofeev, the expeditionary force consisted of 150-200 men with the purpose of collecting yasak from the Teles and punishing the them for past failures to pay. The expedition departed on March 10th from Kuznetsk, and upon arriving to the lake they found it entirely deserted. On March 26th the expedition returned empty handed, with Dorofeev’s explanation being that the Teles had fled into the mountains when they learned that the Russians were coming. This story is difficult to accept because of problems regarding the dates. If Dorofeev is to be believed, his detachment reached the lake and returned back in only 16 days. By constrast, Zubov in 1646 took five weeks just to get to the lake itself. It is simply impossible that Dorofeev completed a round trip to Lake Teletskoye and back in only 16 days. In all likelihood Dorofeev simply lied, for reasons which are not clear. Umansky believes his detachment encountered armed resistance in the upper Chumysh River from the local Azkeshtim Tatars who forced them to return back.90 Regardless of what exactly happened, after 1653 the Teles moved closer to the Zungars and began paying them tribute.91

By the 1670’s Russian interest in Siberia began to diversify away from being solely focused on the collection of furs, and expanded to search for metals and ores. During this period Kuznetsk began to prospect for silver, gold, iron, tin and other metals following rumours of rich deposits in the Altai Mountains. Some years prior, the Cossack Ataman Andrei Federov had reported seeing silver deposits at Teletskoye, which prompted repeated missions to the lake.92 In January 1674 the yasak collectors Grozhevsky and Popov traveled to Teletskoye, and met with Prince Tocheulko of the Teles who informed them of a local ore deposit on a mountain at the mouth of the Chulyshman River. In exchange for this information the Russians gave Tocheulko a piece of cloth that was half an arshin93 long. Another expedition led by Stepan Cherny and Timofei Serebrenninkov reached Lake Teletskoye in March of the same year. They managed to break off a three pound piece of ore and returned with it to Kuznetsk. Afterwards there were no further recorded findings of silver at Lake Teletskoye.94 Russia only turned its full attention to mining and metallurgy in the Altai region several decades later, beginning in the end of the 1720’s. Extensive mining industries were developed across the northwestern and western foothills of the mountains, with the largest mines at Kolvansk, Zmeinogorsk, Ridder and Zyryanovsk. Vast amounts of silver and gold, in addition to tin and iron were mined from those sites, but Lake Teletskoye saw no such activity.

As can be noticed, Russia’s expeditions to Lake Teletskoye in search of silver in the 1670’s received a far friendlier welcome from the Teles compared to past encounters. This was likely the result of two factors: the prospect of trade drew the Teles ever closer into Russia’s orbit, and Russians demands became less onerous. In all likelihood the Teles slowly reconciled themselves to Russia once it became clear the Russia’s presence in Siberia was permanent.

After the initial series of violent Russian campaigns aimed subduing the Teles, life at Lake Teletskoye became calm once again. Only rumours and false alarms occasionally disrupted the quietness at the lake. In October 1687 information reached Kuznetsk of a battle between Zungars and Mongols, presumably Khalkhas, in the upper reaches of the Chulyshman River about 125 verstas from the lake. The battle likely took place on the Chui steppe, with Yenisei Kyrgyz, Sayan tribes, Teleuts, and possibly even Teles reportedly having fought alongside the Zungar force. Little is known of this battle, and likely dozens of such skirmishes took place in the Altai region between the Zungars and Khalkhas during their centuries of warring.95 Later in 1807 a large Chinese force armed and prepared for battle was reportedly spotted beyond the lake, on the far side of the Altai Mountains. The Russian military authorities at Biysk and Kuznetsk viewed this as being potentially a Chinese army sent to invade Siberia. Military reserves and the civilian population were mobilized, but in the end nothing came of this incident, it was merely a false alarm.96 What reason or plans this Chinese army had for marching up the Altai Mountains remains a mystery.

Conclusion

By the ascension of Peter the Great to the Russian throne, Lake Teletskoye and the Teles were firmly within Russia’s sphere of influence. While Russia’s claims were contested by the Zungars and the Teles often paid tribute to both, the Teles no longer offered resistance and had largely accepted Russian sovereignty. But the situation was different in the lowland steppes north of the Altai Mountains. There, the Teleuts still held out against Russian power and beyond them remained the Zungars who still regularly raided Russian territories in Siberia. Plagued by their own lack of numbers, poor supply and in particular, their inability to challenge Zungar cavalry forces on the steppe, Russian ambitions to expand further up the Irtysh and Ob Rivers remained dormant for the remainder of the 17th century. This only began to change in 1709 under Peter.

In June 1709, less than a month before to the Battle of Poltava, which sealed Sweden’s fate in the Great Northern War and cemented Russia’s rise to great power status, Russia’s nearly 100 year old ambition to construct a fort at the confluence of the Biya and Katun Rivers was reactivated. Over 600 people from Kuznetsk were sent to build the Bikatun ostrog, which was completed within two weeks. The fort soon came under attack by the Teleuts, but they were repelled with ease. Despite this, a year later in August 1710 a force of Zungars under Dokhur-Zaisan encountered the Bikatun ostrog on their way to raid Kuznetsk. As it blocked their way to continue further, the Zungars besieged it instead. The ostrog was only held by only a few dozen Russians, and after a short three day siege the Zungars with some Teleuts set parts of the walls and inner buildings on fire.97 The Russian garrison fled back to Kuznetsk leaving behind a scorched wreck of an outpost.

Even more than the Teleuts or other local Siberian peoples, the principle obstacle to Russian ambitions in southern Siberia remained the Zungars. This obstacle was soon overcome a few years later, with Russia’s creation of a fortified frontier line along the Irtysh River. In the middle of the 1710’s a series of expeditions were dispatched from Tobolsk with the purpose of reconnoitering the Irtysh River. The first was headed by Ivan Dmitrievich Bukholts in 1715-1716, with the goal of marching to Yarkent in the Tarim Basin to seize its reported “golden sands.” This expedition ended in failure.In early 1716 the expedition’s camp at the Yamyshev Lake came under siege by a Zungar force and was forced to retreat back down river to Tobolsk. While on the their way back, Omsk was founded on the Irtysh, which later served as Russia’s window to the steppes and headquarters of the Irtysh Line. A few years later in 1719 Ivan Mikhailovich Likharev was dispatched from Tobolsk in command of a new expedition with the more modest objectives of merely exploring the upper reaches of the Irytsh River and constructing fortresses if possible. Unlike Bukholts who almost immediately met fierce resistance from the Zungar Mongols, Likharev’s expedition fared much better. To the expedition’s great luck, the Qing Dynasty had recently invaded Tibet and deposed the pro-Zungar regime in Lhasa just prior to its departure. Distracted by events to their south and east, the Zungars had no choice but to remain passive in response to the Russian advance into their north. In fact, the increased Russian presence on the Irtysh was even welcomed by the Zungars as it offered the possibility of further trade. Unhindered, Likharev reached the headwaters of the Irtysh in the southern Altai region, and on his return journey he founded the fortresses of Ust-Kamenogorsk, Semipalatinsk and additional smaller outposts along the Irtysh. By 1720 these fortresses and outposts formed a chain that guarded southern Siberia from the nomadic Zungars and Kazakhs on the steppe. The line was extended further south with the establishment of the Bukhtarma Fortress in 1763, and with it the entirety of the northern Altai region was enclosed inside of Russia.

With the construction of the Irtysh Line the Zungar threat was effectively neutralized. Siberia’s southern frontier was sealed, and this seal was only tightened in subsequent decades, but more immediately, Russia’s ambitions at the Biya-Katun confluence were now finally realizable. In June 1717 a new expedition was sent out from Kuznetsk to the Biya-Katun confluence, and by the end of that month a new ostrog was built. In 1732 Bikatun was renamed as Biysk, its current name, and later in 1747 under the reign of Empress Elizaveta Petronova Biysk along with Kuznetsk became the centers of a new fortified line meant to guard Siberia’s southern frontier. Named the Kuznetsk-Kolyvansk Line, this linear system stretched from Kuznetsk to Biysk, and followed a southwestern line through Zmeinogorsk to Ust-Kamenogorsk. The Kuznetsk-Kolyvask Line together with the Irtysh Line and the Ishim and Novo-Ishim Lines formed the Siberians Lines, which sealed Siberia’s southern frontier from the Altai to the Ural Mountains off from the steppes. The fortifications along these lines were expanded and modernized up until the reign of Catherine the Great in anticipation of a possible attack by the Qing Dynasty, but this never came. Having annihilated the Zungars in the 1750’s and reached as far as lakes Zaisan and Balkhash, the Qing Dynasty remained satisfied with its inner Asian frontiers for the remainder of its lifespan as a state.

While the preparations for a Chinese invasion were largely for naught, in the 1850’s the settlements along the Siberian Lines would serve as launch pads for the conquest of Central Asia. Picking up where Bukholts and Likharev left off, Siberian Cossacks pushed south towards Semireche and the Tianshan Mountains in beginning in the 1840’s. In 1854 Verny was built, modern day Almaty in southeastern Kazakhstan, and in later years the Khanate of Kokand was push back into the Fergana Valley was Russia expanded westwards towards the Syr-Darya. It was only with the resource base and supplies built up in Siberia that this later conquest of Central Asia was possible. The grains and metals produced in the lowlands north of the Altai Mountains were particularly invaluable to Russia’s expansion across the Kazakh steppe. The area around Biysk ultimately proved to be a small bit of paradise in the otherwise harsh land of Siberia, with Fedor Nikolaevich Usov, an ataman in the Siberian Cossack Army, noting the general lack of poverty in the region and described the region as such: “Here we see the luxurious development of forest vegetation and rich flora, the animal world is very diverse. The mineral wealth of the Altai Mountains is universally known.Mountain valleys and slopes are covered with excellent black-earth soil, in which in the sultry heat moisture is maintained from the numerous streams and springs; therefore corn failures are extremely rare here.”97 For the Old Believers who were drawn the Altai Mountains beginning in the 1720’s, those who would later become known as the kamenshchiki, or “rock people”, the valleys just to the south of the lowlands were thought to be the place where they would find Belovodye, a “land of peasant justice where milk and honey flow.”98

As for Lake Teletskoye itself, once again in 1717 the lake was surveyed for the purposes of building an ostrog, but the same problems remained and nothing was built.99 Only in 1956 was a road finally built, allowing cars and other vehicles to reach the lake. Largely due to the lake’s remoteness, cut off the from the lowlands by inaccessible mountains, it has seen minimal Russian colonization. Only one village on the lake is majority ethnic Russian, which is Artybash located at the head of the Biya River. The rest of the small settlements along the lake and up the Chulyshman remain Teles, who are known today as Telengits.

While the history of Russia’s expansion into the Pacific Ocean, Central Asia and the Amur Valley are fairly well known, the history of how Russia filled out into the giant continental space that it conquered between the Urals and the steppes has remained a largely untouched topic by English language historians, with topics such as the expansion into the Altai-Sayan range and the creation of the Siberian Lines being almost entirely overlooked.

Like elsewhere across Siberia, Russia expanded into the Altai region along its navigable waterways and then built settlements from where yasak could be collected. But quickly Russian encountered rival states with powerful military forces capable of not only resisting Russian expansion, but had the potential to even drive Russia out of the region. This prompted a shift from pure expansion to the creation of defenses for what already been conquered. As Russia lacked the man power and supplies to confidently secure its Siberian territories, it aimed to secure “natural frontiers” for itself. In other words, geographic points that would act as force multipliers for defending forces and which would impede enemy attacks. It is only natural that Russia came to view the Altai Mountains and the Irtysh River as ideal geographic features to anchor its frontiers to. Control over Lake Teletskoye in particular offered the possibility of bringing the entire Ob River Basin fully under Russian influence.

It is worth noting just how daring and reckless Russia’s initial southward movements toward the Altai Mountains were. As can be seen in the expeditions by Pushchin in 1632 and Bukholts in 1715-1716, these forward moves often ended in catastrophe. Nor were they isolated incidents. Expeditions to Khiva in 1717 and 1839 ended even worse, not to mention Peter the Great’s campaign to the Prut River in 1710-1711, where he was nearly captured by the Ottoman Empire. Russia’s initial assaults into Chechnya in 1995 and Ukraine in 2022 are modern examples of a pattern by Russia of highly aggressive initial assaults that end badly. As can be seen in southern Siberia and elsewhere, while foiled in the short term, Russia rarely ever abandons its ambitions. Russia waited for nearly a century to build an ostrog at the confluence of the Biya and Katun Rivers, while in the case of Khiva, it waited nearly 150 years after its first failed attempt to conquer the khanate. In the late 17th century Russia was forcefully ejected from the Amur Valley by the Qing Dynasty, but nearly 200 years later it reactivated its ambitions there and annexed the left bank of the Amur once the Qing Dynasty had sufficiently weakened. In the 19th century Russia spent 60 years in grinding war against the Caucasian highlanders in order to conquer the mountains, only to spend another 20 to reconquer Chechnya during our time.

Once Russia has a target in its sights it rarely ever lets it go, even if it needs to wait hundreds of years to finally make its move. This was remarked upon by Nietzsche, who saw this characteristic as being both a great strength of Russia’s, but also a great danger to Europe: “it (its will - AC) is strongest and most amazing by far in that enormous empire in between, where Europe, as it were, flows back to Asia—namely, in Russia. There the strength to will has been long accumulated and stored up, there the will… is waiting menacingly to be discharged.”100

Bibliography

Bocharnikov, Vladimir N. and Alina N. Steblyanskaya (Editors). Humans in the Siberian Landscapes: Ethnocultural Dynamics and Interaction with Nature and Space. Cham: Springer, 2022.